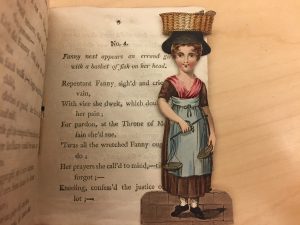

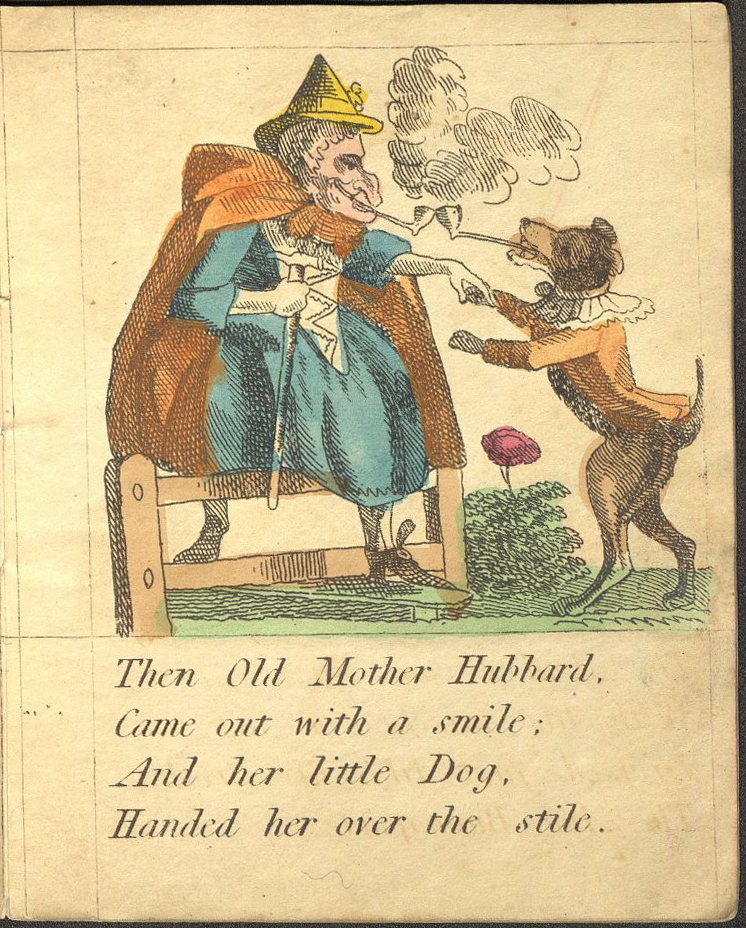

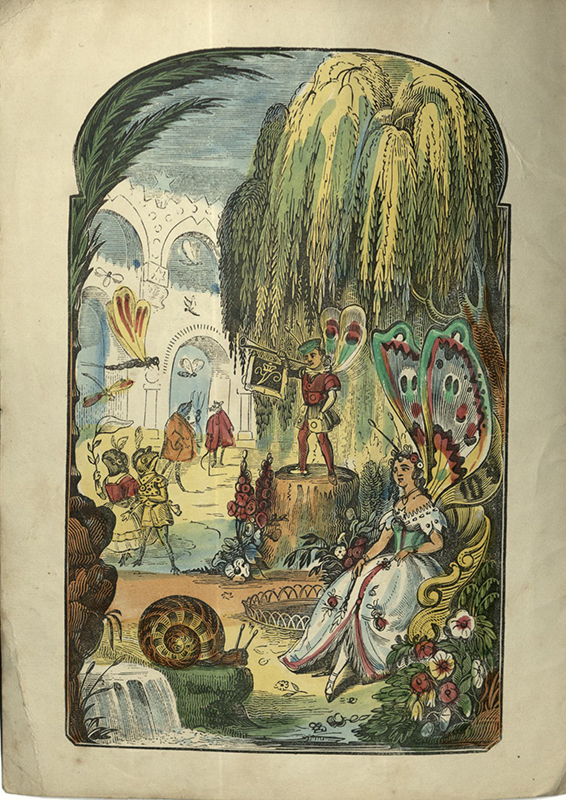

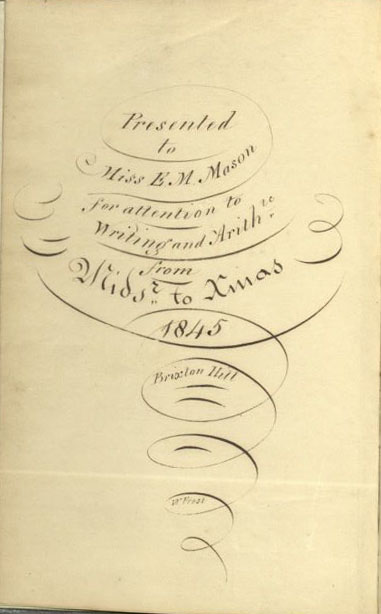

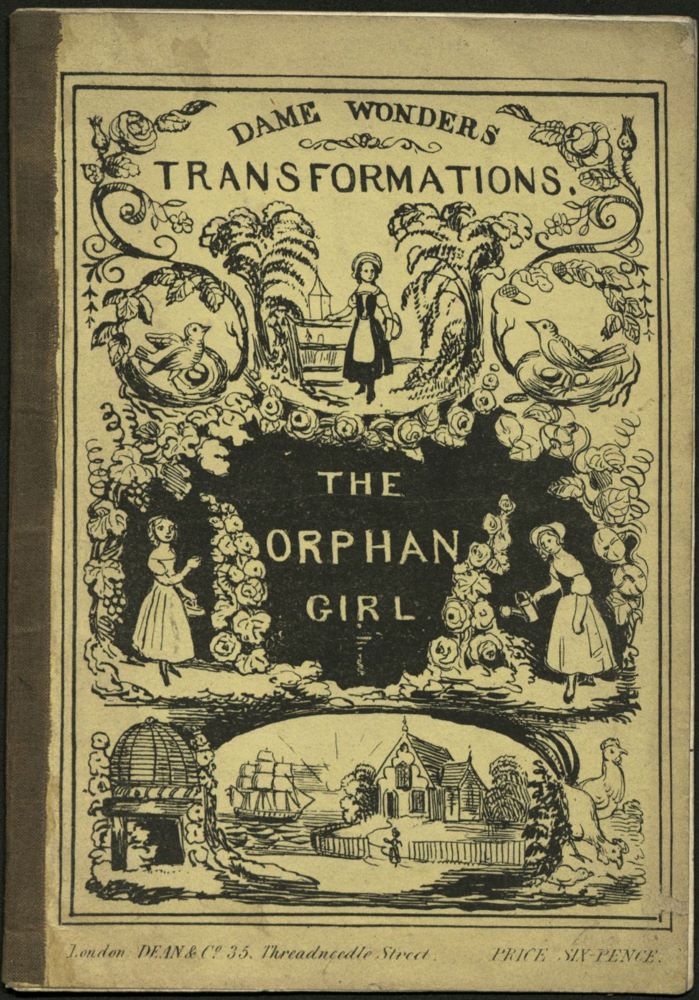

Dean & Co. was an early and prolific publisher of toy and movable books for children: pop-ups, pantomime books, “peepshow” or tunnel books. Their first line of novelty books was the series Dame Wonder’s Transformations, books with a hole cut in each page through which the face of the main character appears, surrounded by the events of the story. The Orphan Girl, published between 1843 and 1845, is a charming example of this technology.

The Orphan Girl, published between 1843 and 1845, is a charming example of this technology.

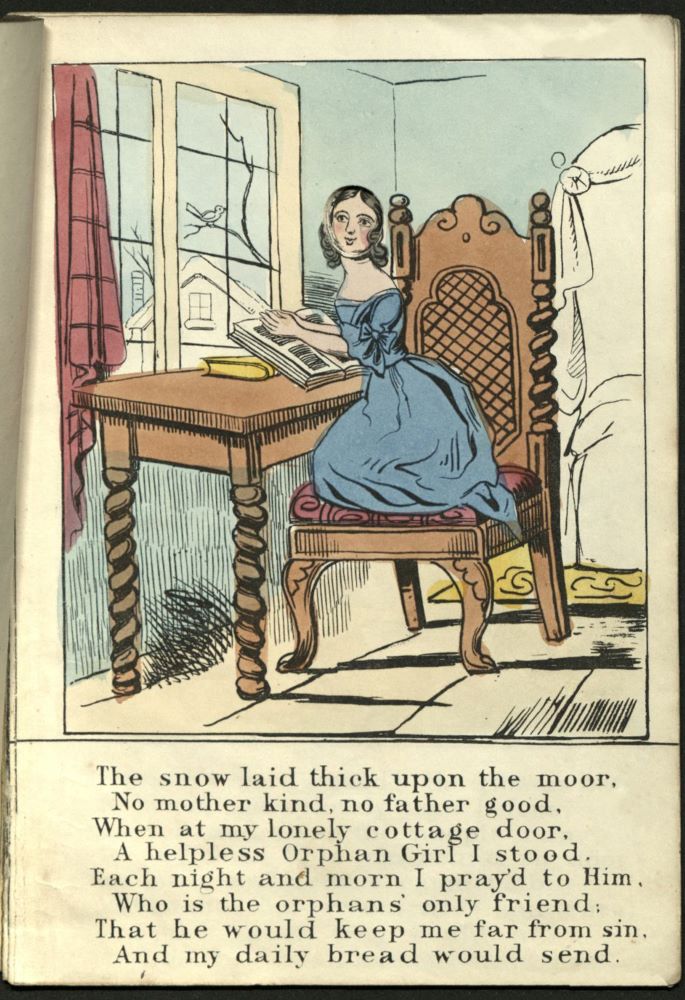

The story is told in the first person by the “orphan girl”, who appears to be in her mid-to late teens at the beginning of the book. She is left alone, although in possession of a cottage, and she calls upon God to keep her from sin and to supply her needs.  As a result of her earnest piety, her garden provides abundant bouquets which she sells to the wealthy.

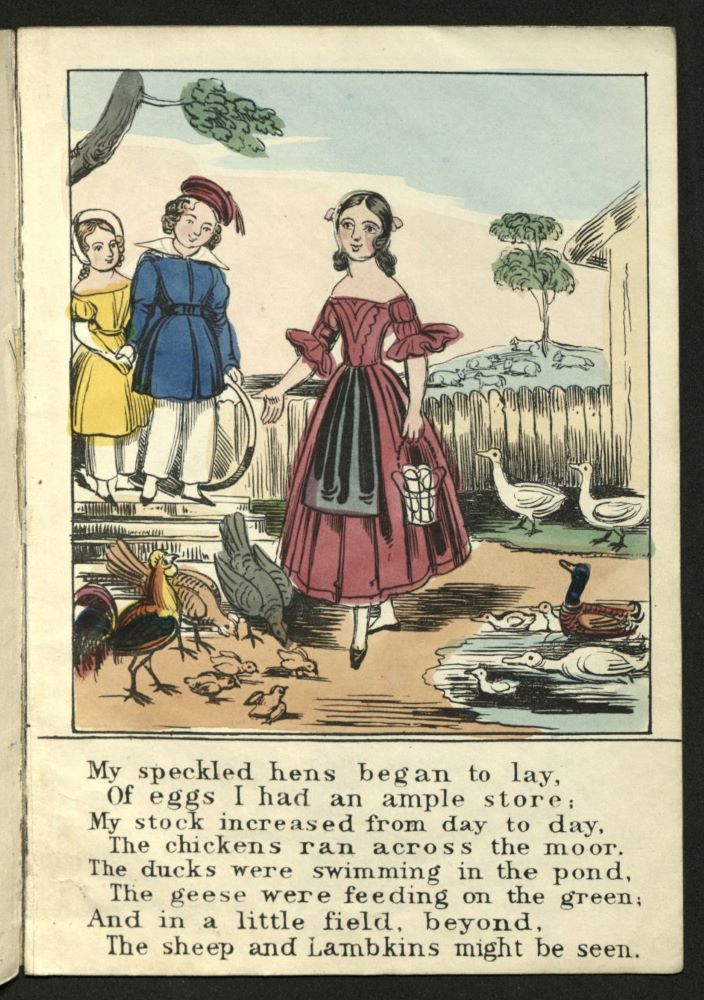

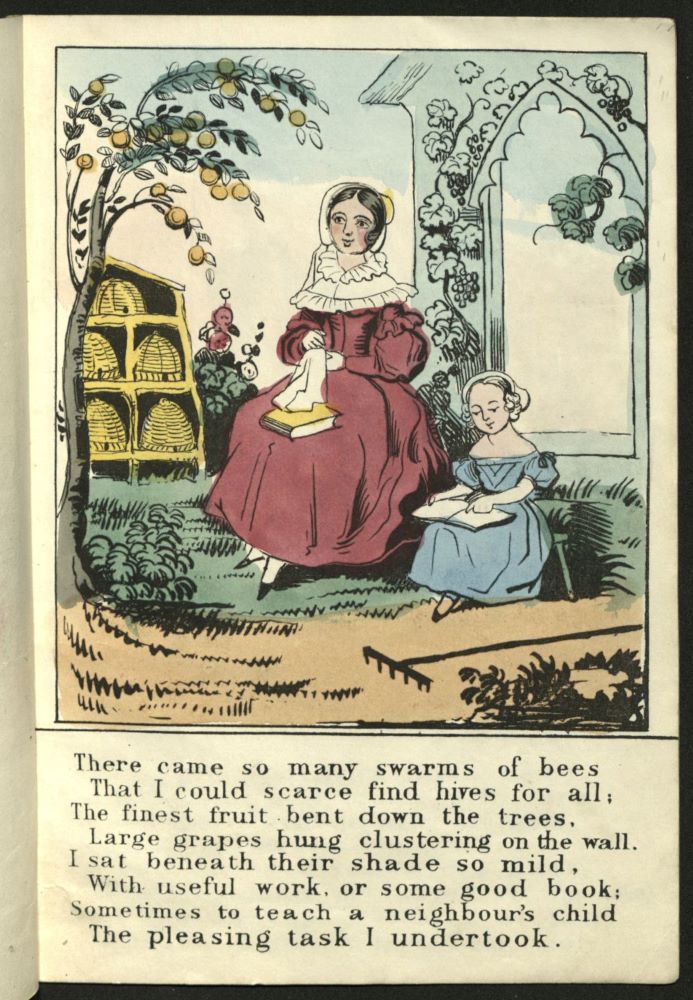

As a result of her earnest piety, her garden provides abundant bouquets which she sells to the wealthy.  In addition, her domestic fowl and sheep increase prodigiously, bees swarm to her home, and her fruit trees and vines bear heavily.

In addition, her domestic fowl and sheep increase prodigiously, bees swarm to her home, and her fruit trees and vines bear heavily.  She occasionally teaches a neighbor’s child to read, apparently as a leisure activity.

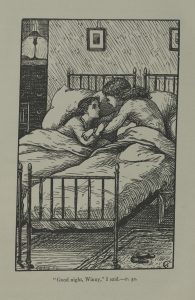

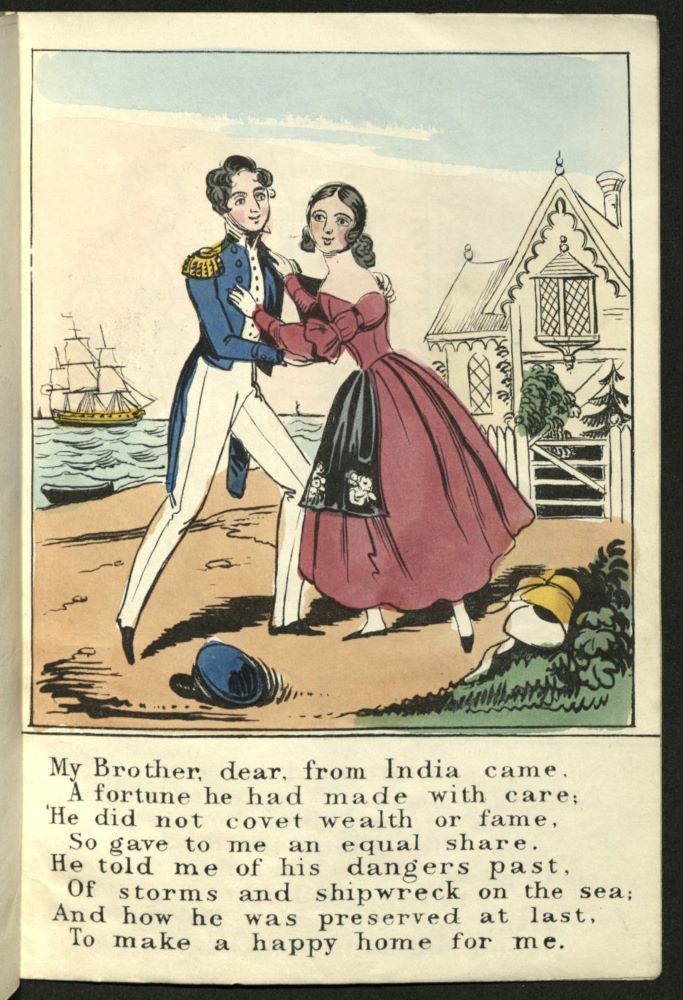

She occasionally teaches a neighbor’s child to read, apparently as a leisure activity.  Suddenly, her brother returns from India, having made a fortune, and provides the means for the two of them to live comfortably in the cottage.

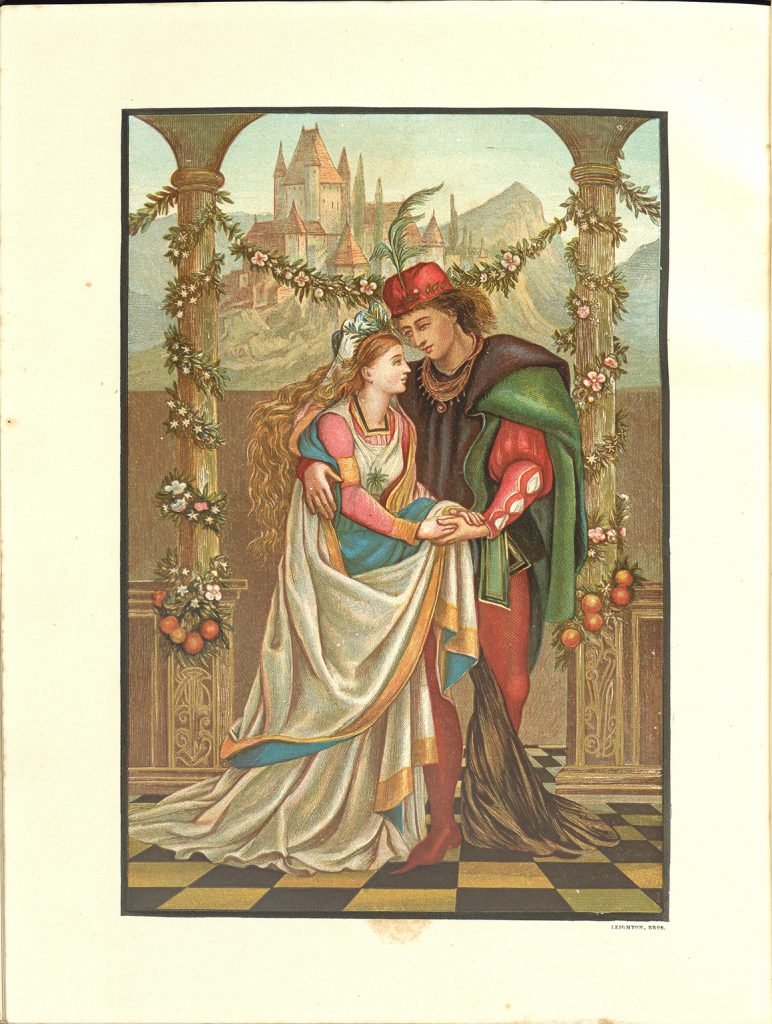

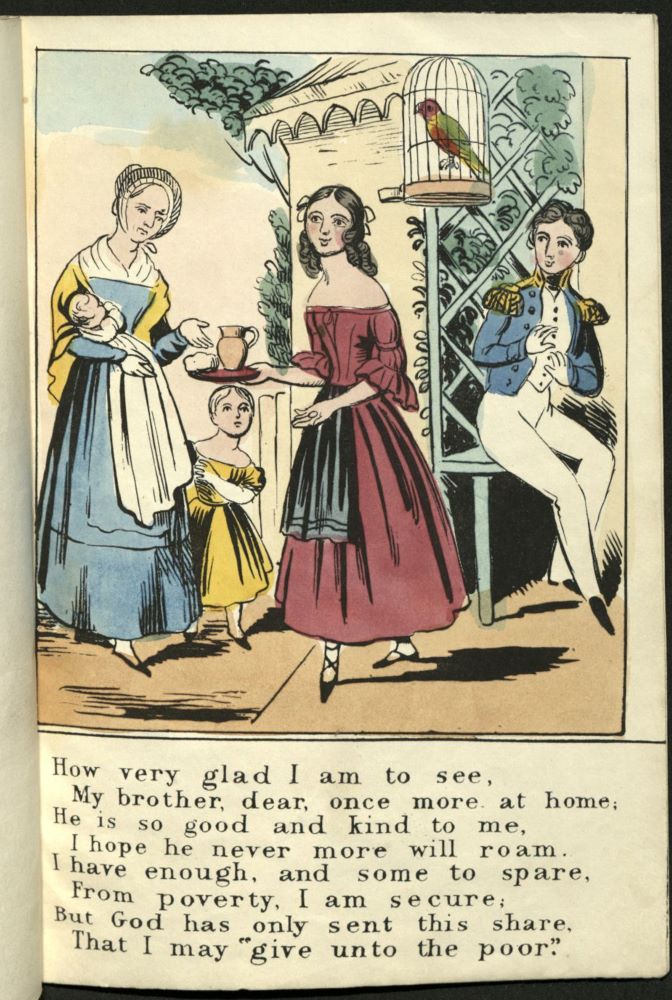

Suddenly, her brother returns from India, having made a fortune, and provides the means for the two of them to live comfortably in the cottage.  In the last scene, supplied abundantly herself, she gives bread and drink to an impoverished neighbor.

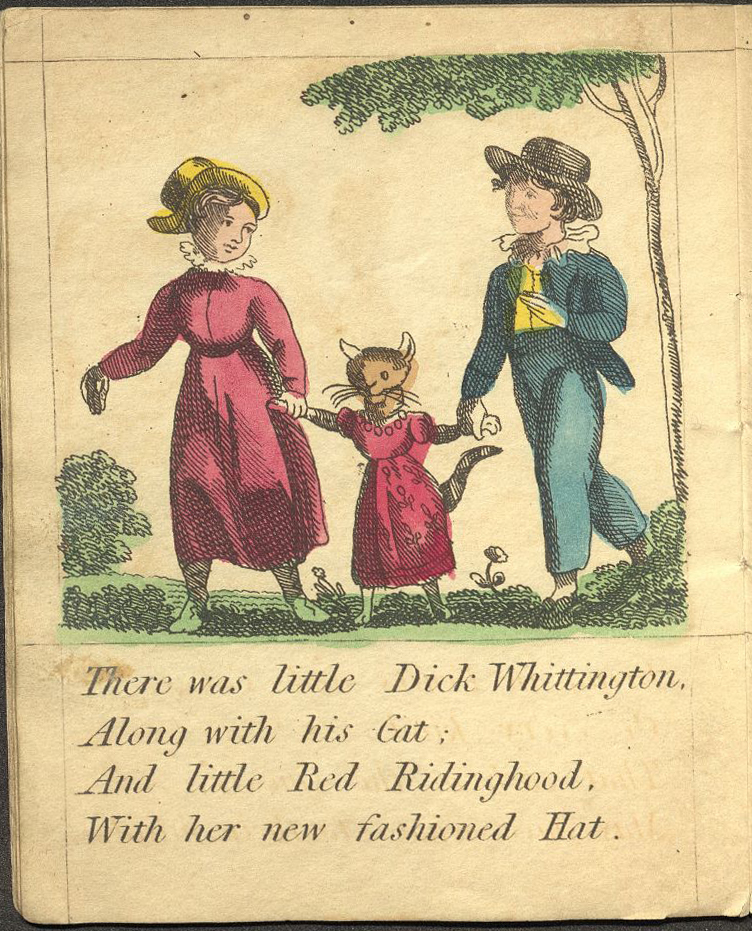

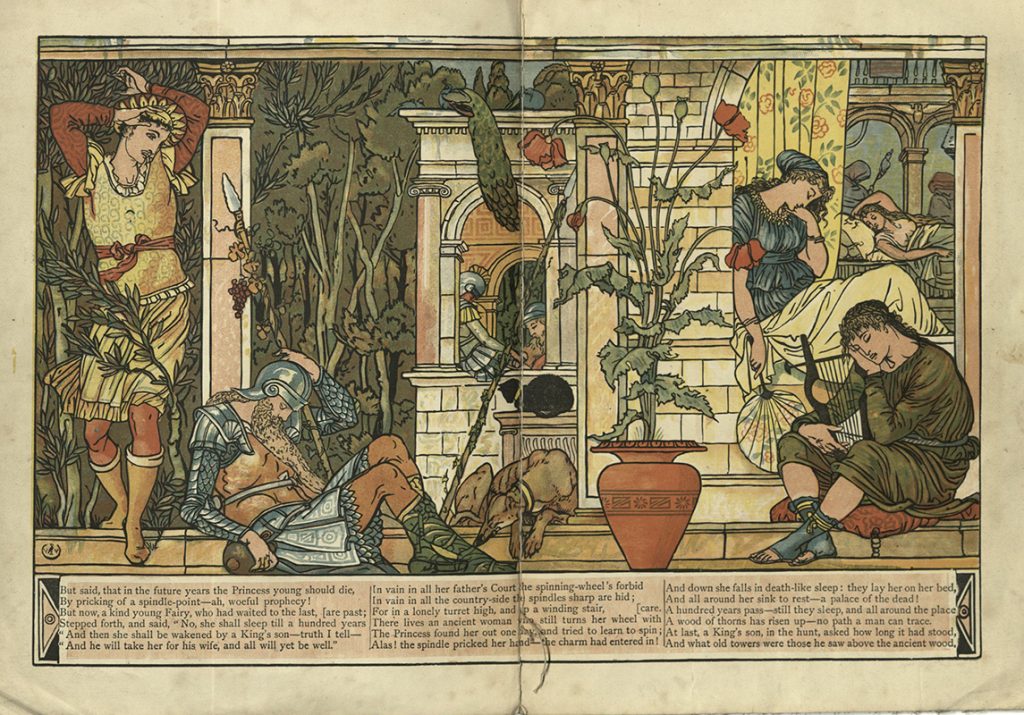

In the last scene, supplied abundantly herself, she gives bread and drink to an impoverished neighbor. The narrative is related to the most famous children’s book of the eighteenth century, Little Goody Two-Shoes, although in The Orphan Girl, the account is condensed to an extreme. The original, first published in 1765, tells the story of a sister and brother whose parent die when the children are small. They are separated, and the story follows the sister who lives at first in extreme poverty in the country, gradually gaining the respect and trust of her fellow villagers. By the time she is in her early teens she supports herself by going house to house daily, teaching younger children to read. When the schoolmistress retires, she is chosen to replace her. Her competence and kindness induce a local gentleman first to employ, then to woo her. Their wedding is enlivened by the return of her now wealthy brother, and she lives afterward as a model of prudence, piety, and effective charity. The Libraries do not, unfortunately, have an early copy of the book, but you can read it on the Internet Archive.

The narrative is related to the most famous children’s book of the eighteenth century, Little Goody Two-Shoes, although in The Orphan Girl, the account is condensed to an extreme. The original, first published in 1765, tells the story of a sister and brother whose parent die when the children are small. They are separated, and the story follows the sister who lives at first in extreme poverty in the country, gradually gaining the respect and trust of her fellow villagers. By the time she is in her early teens she supports herself by going house to house daily, teaching younger children to read. When the schoolmistress retires, she is chosen to replace her. Her competence and kindness induce a local gentleman first to employ, then to woo her. Their wedding is enlivened by the return of her now wealthy brother, and she lives afterward as a model of prudence, piety, and effective charity. The Libraries do not, unfortunately, have an early copy of the book, but you can read it on the Internet Archive.

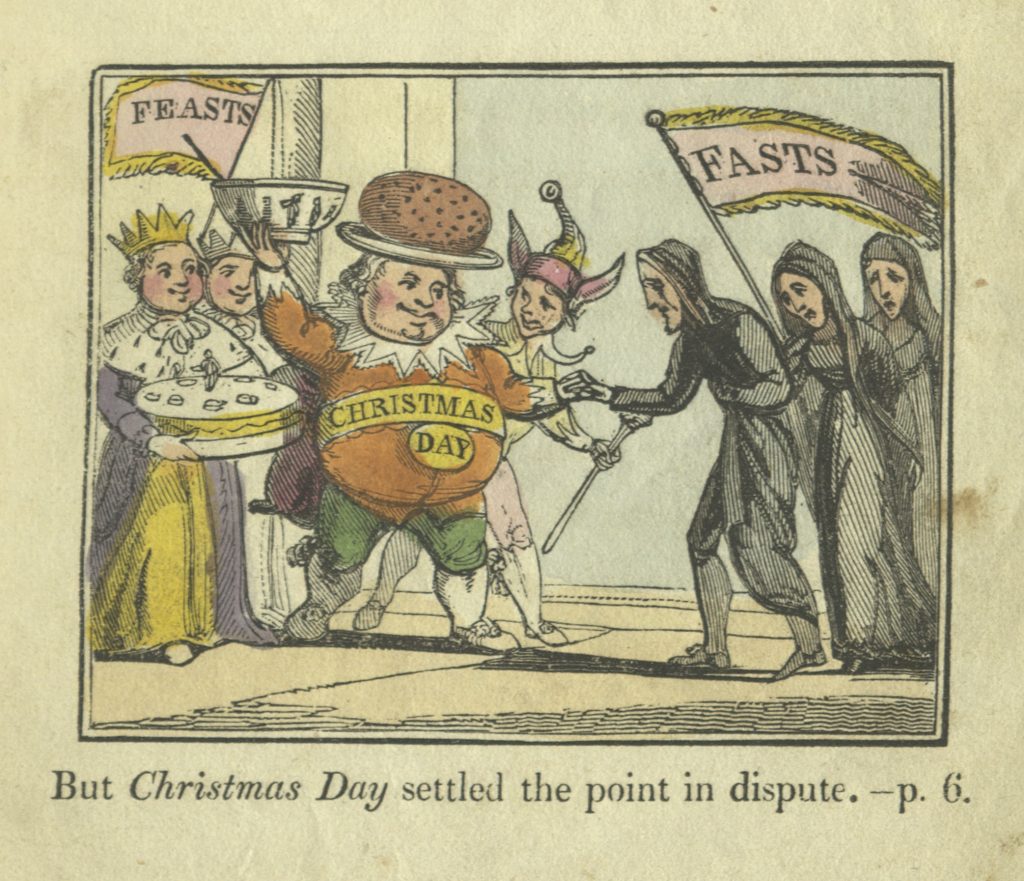

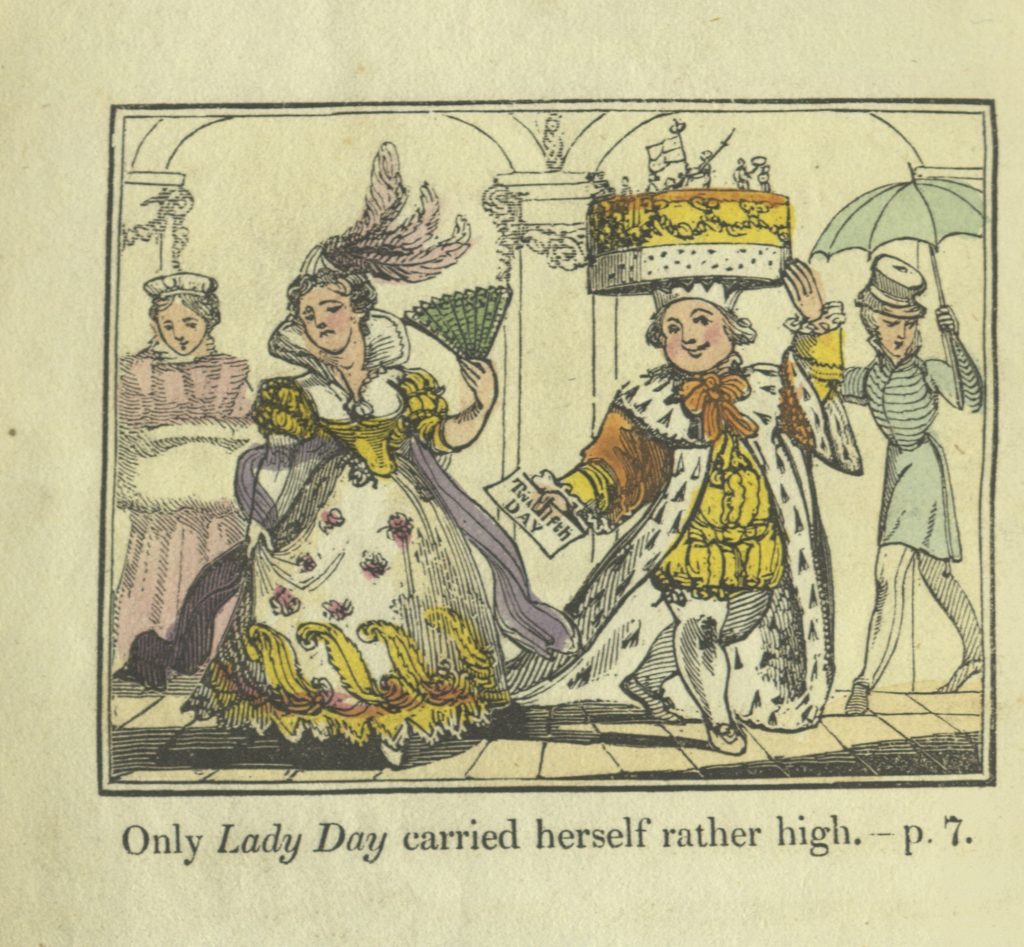

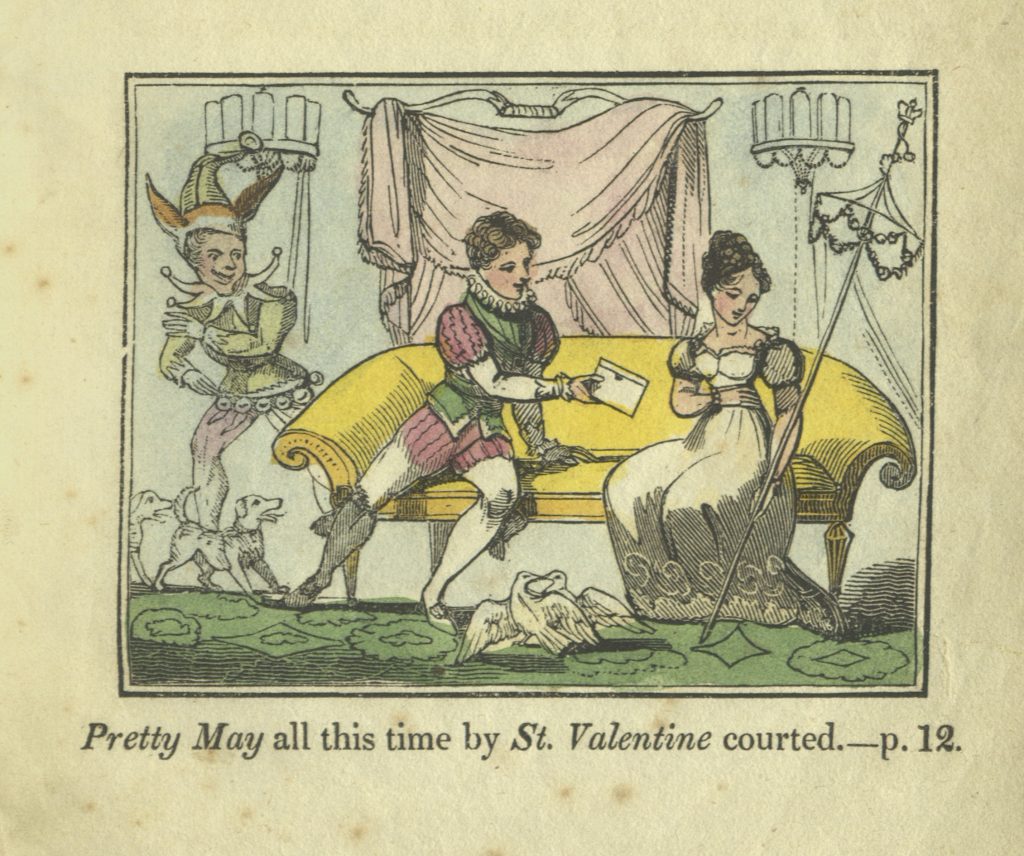

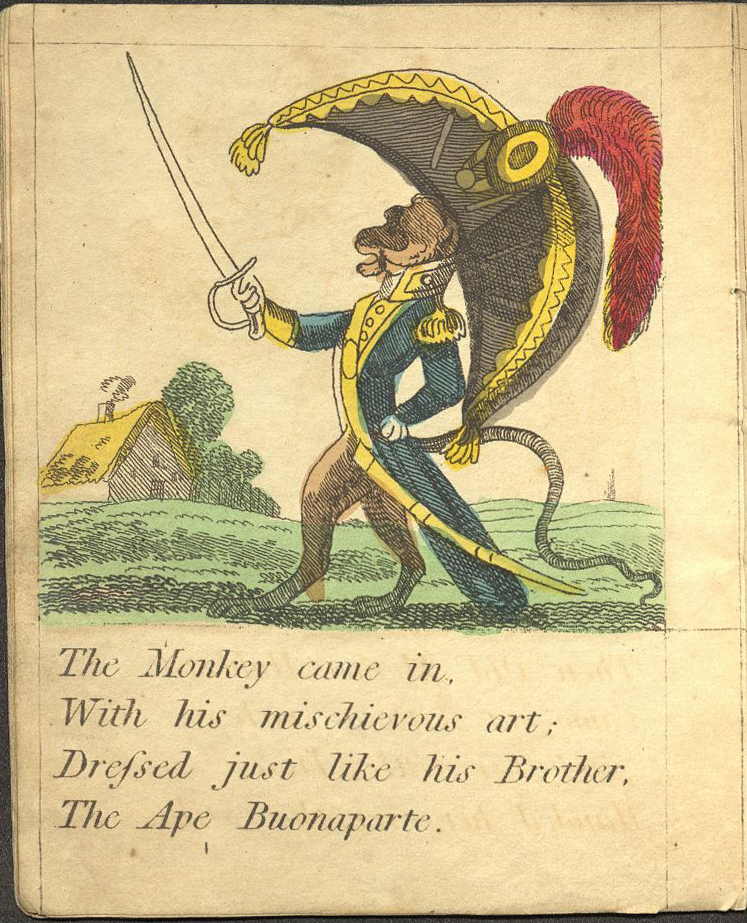

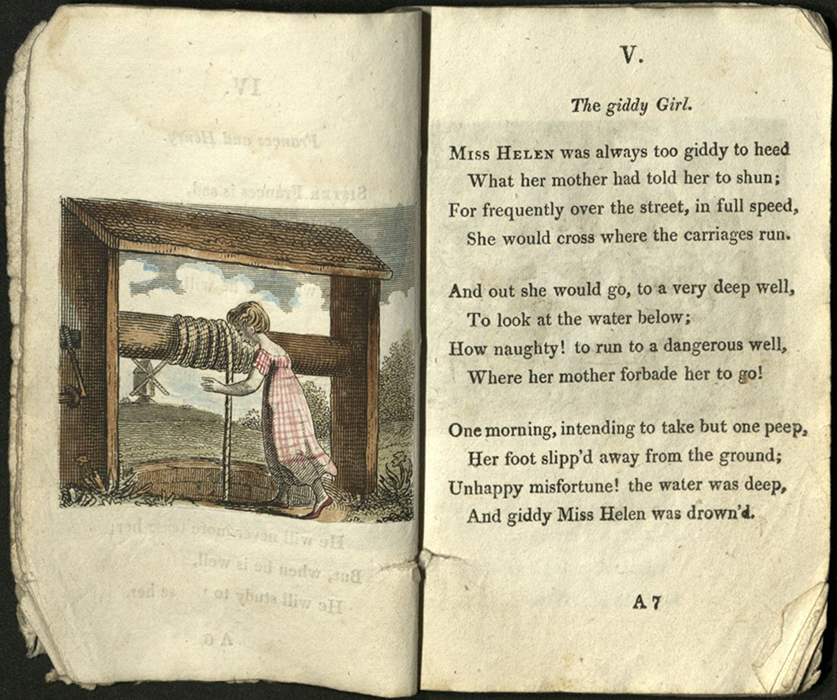

Of course, if you reduce a story from 100 plus pages to a bare six images you must simplify the narrative. Goody Two-Shoes appeared in dozens of later, shorter versions, many of which suggest that the reader was expected already to know the story. But the differences in these two accounts give us an opportunity to reflect on the lessons conveyed by books to their young readers. The “orphan girl” is devout and trusts God, and she is rewarded for her faith and piety by prosperity, without any effort beyond prayer. Although Goody Two-Shoes also conveyed numerous religious messages, it featured a protagonist who made her way in the world though dogged hard work, good nature, and intelligence. Both are historically acceptable role models – but what a difference in the influences the two might have on a young female reader.

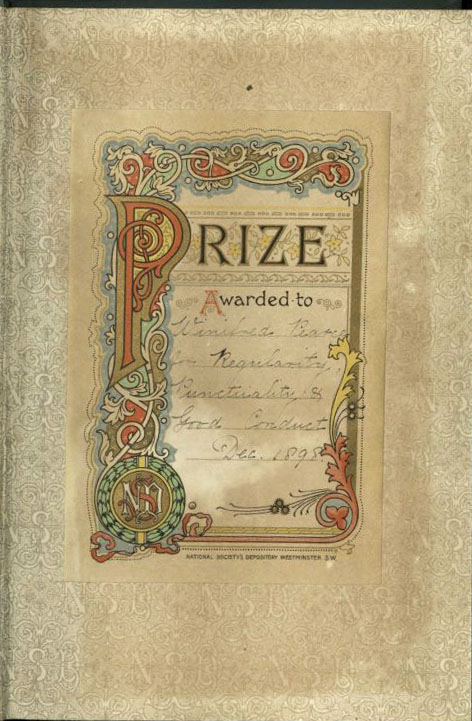

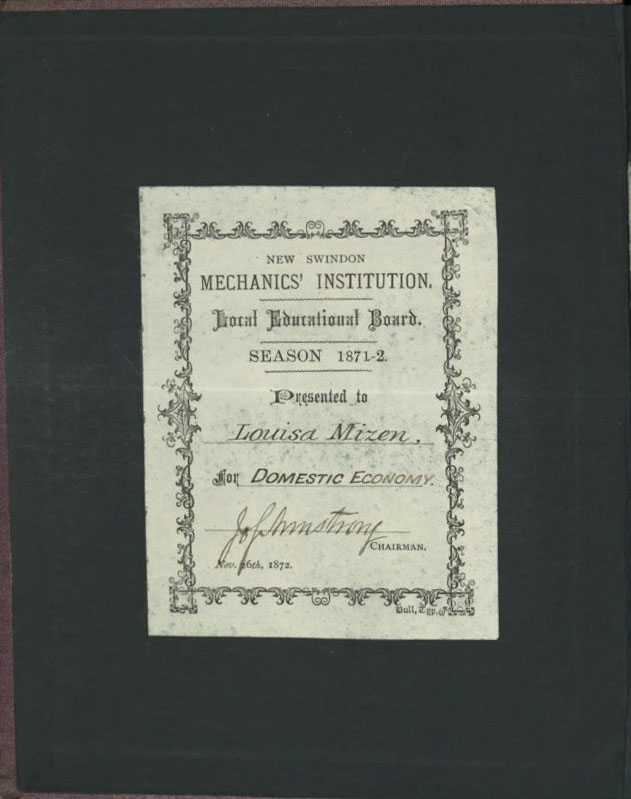

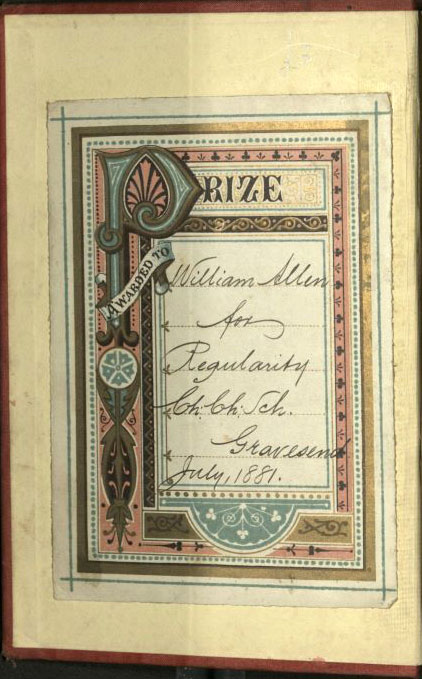

The Orphan Girl. London: Dean & Co., 35 Threadneedle Street, 1843-1845

The Orphan Girl. London: Dean & Co., 35 Threadneedle Street, 1843-1845