On June 6th-9th, Mark Mudge (President), Carla Schroer (Founder and Director), and Marlin Lum, (Imaging Director) of Cultural Heritage Imaging (CHI) visited Bryn Mawr College and trained interested recent alumnae, students, faculty, and staff in Photogrammetry for Scientific Documentation of Cultural Heritage through a four-day workshop. Mark, Carla, and Marlin were a wonderful and welcoming team that made photogrammetry very understandable and accessible to a group with a widely disparate set of skills. CHI is same group responsible for the creation of Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI), a type of computational photography utilizing a movable light source on an unmoving surface with a static camera position that was introduced to the study of objects in Special Collections in 2014. RTI is used presently in Bryn Mawr College’s collections and in many other institutions world-wide. CHI’s training and standards for photogrammetry are another important effort of this group for creating practical methods for digital imaging and preservation that will now be available at Bryn Mawr College.

For those of you who have not previously encountered photogrammetry, it is a type of computational photography, or digitally captured and processed images, that combines a series of carefully captured images to produce precise 3D surface data. While the technology has been around for awhile, photogrammetry has improved over the years through refined camera technologies and techniques, as well as through improvements in the software. The process is relatively quick, once you know what you are doing, portable, and uses standard photography equipment. All of these factors make it a very accessible technique to an archaeologist such as myself, both for fieldwork as well as for travelling to specific museums and sites in the future. The resulting models can be measured with a high degree of accuracy, even when the subject is not present or even available in the future. Objects may not be accessible to scholars for a variety of reasons, varying from being in a closed museum, located across the country or even the world, as well as for more dire reasons such as if an object has been lost, damaged, or completely destroyed.

Camera set up and Mark showing Zach Silvia, Sarah Luckey, and Del Ramers how to adjust the settings through the laptop

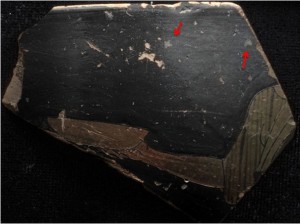

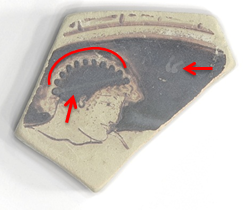

The trainees at this four-day workshop included individuals from collections management, librarians, digital scholarship specialists, anthropologists, and archaeologists, as well as others who joined for specific lectures. In particular, many of us were interested in the use of photogrammetry for the study of artifacts, architecture, sondages, and even bones, to create models. These scaled models can be used to measure features of these objects, to accurately record condition, to allow for more direct comparisons between scaled models of objects, as well as to serve as a digital archive for the future. As an archaeologist who studies Greek vases, objects which are spread out in museums and private collections around the world, can be sold and moved, lost, or broken, and often have limited angles in published photographs, it was very important for me to learn to create accurate models and to understand how to identify the inaccuracies I encounter in models as part of this training.

The training divided into lectures and practical lessons, which consisted of both camera shoots and computer processing of the images. The practical lessons featured us breaking up into groups, so that everyone could get hands-on experience. Most of the training took place in the Carpenter Library, with excursions around campus to shoot particular objects as the subjects of our practical lessons. These objects include the two casts of reliefs and books in Carpenter Library, a plaque and marble sarcophagus in Thomas Cloisters, two vases in Special Collections, and the marble bench outside of Dalton. The diversity of subject objects provided us with experience in capturing images for photogrammetry in a variety of settings and with objects of varied scale that each required their own problem-solving.

Carla showing trainees (Caroline Vansickle, Sarah Luckey, Marianne Weldon, Zach Silvia, and Danielle Smotherman Bennett) how to adjust camera settings before a large project

Those of us who own personal Digital SLR cameras learned how to capture images for photogrammetry on our own cameras, but others used the cameras owned by CHI or Bryn Mawr College. The other equipment we used included a remote switch, remote flash(es), a monopod, a tripod, color card, scale bars, and a turntable, although not all of that was required for every shoot. For instance, at times we could use the ambient lighting, especially outdoors, but other times we needed to use flash or two in order to create an even illumination over the object surface. Similarly, we could only use the turntables occasional since a turntable is only practical for small, movable, and light-weight objects. Occasionally we used other materials, such as when we had to find make-shift back drops to cover reflective backgrounds, or use white foam board to reflect light.

Mark observing the creation of a model by one team (pictured: Matthew Jameson, Camilla MacKay, Del Ramers and Alicia Peaker)

After pre-processing the images through Adobe Bridge, we produced models through the use of Agisoft Photoscan Professional and the very capable Visual Resources computers. The resulting models and data can be shared with scholars around the world through as the models themselves through photogrammetry software, but also as 3D PDFs, which can be viewed in many PDF viewers. Thus, along with being a method of digital archiving of these objects, photogrammetry models can also provide more accessibility to collections.

Along with learning about how to capture and create accurate photogrammetry models, Mark, Carla, and Marlin also taught us about creating and sending verifiable data with our models. One aspect of this is generating a report within the photogrammetry software itself that contains information as to the camera information, number of images, camera locations, camera calibration, scale, error, and processing procedure and time. Another aspect is the importance of recording the process in a Digital Lab Notebook, which can be sent along with the data itself and the report to scholars looking at or using the model. This recording process includes not only the camera specifications, which are already included in the report, or only the subject of the project, but also who was involved, what equipment was used along with the camera, where and when the images were captured, and other possibly significant information.

Through the very capable training we received, we can now share the methodology that we have learned with others in the community. We can also apply the methodology and use the resulting photogrammetry models to our own research. Photogrammetry for scientific documentation has many implications for the future study of objects and architecture, in which Bryn Mawr College can now take part.