By Isabella Nugent

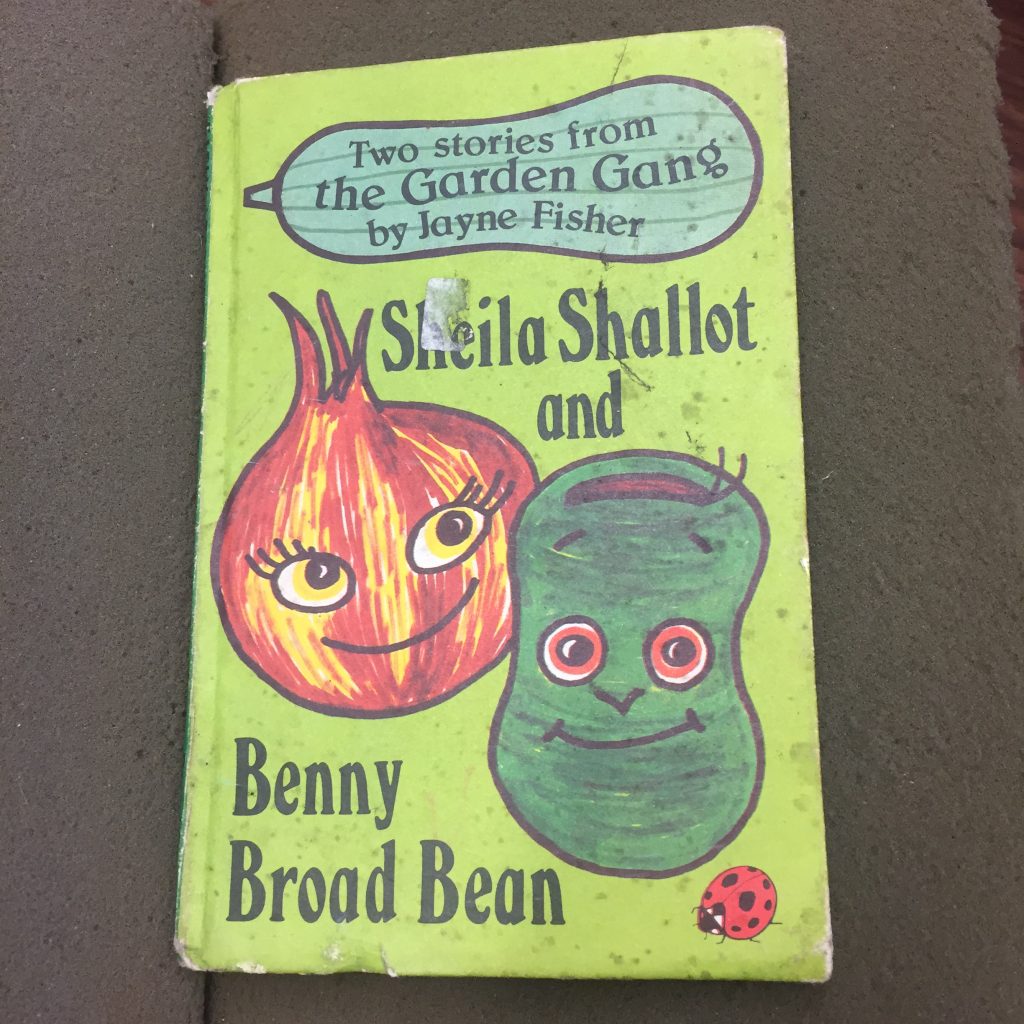

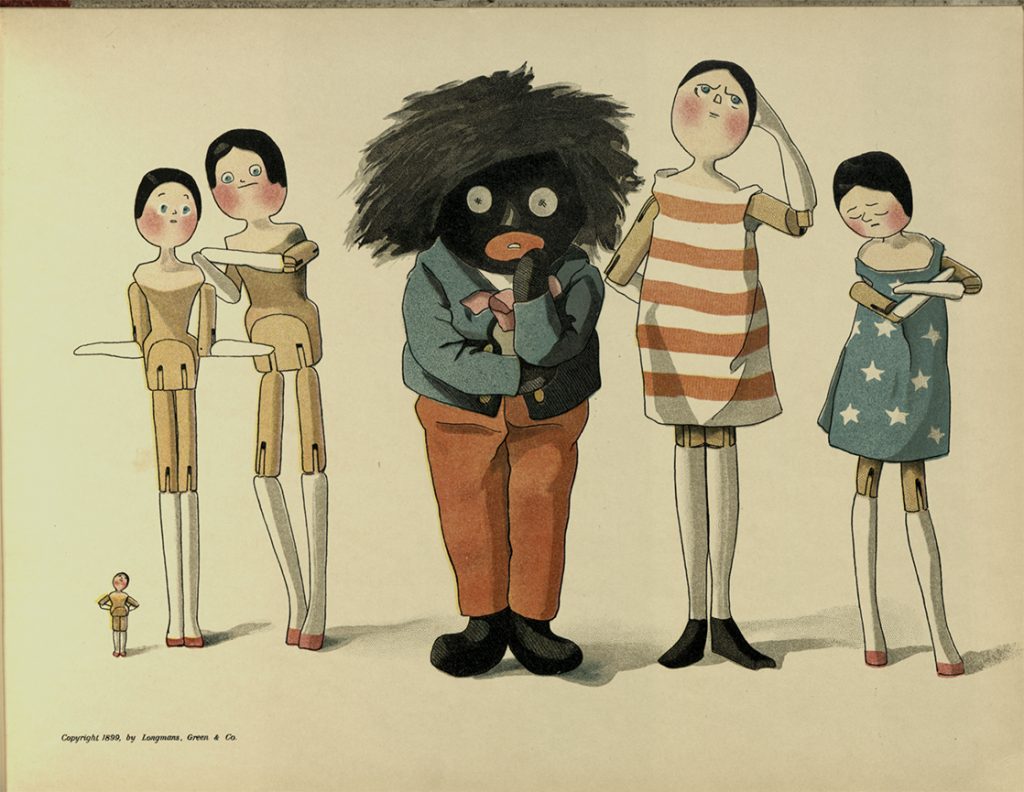

Over the course of the summer, the most treasured literary characters from my childhood swam out of the 634 boxes we unpacked, cleaned, and shelved. But between the hobbits and the Beatrix Potter bunnies, appeared a kind of character I’ve never seen before in my own books: the golliwog. Golliwogs are dolls with large, white-rimmed eyes, cartoonishly big lips, frizzy hair, and jet black skin. The golliwog is an example of a “darky”, a racist representation of Blackness intended for white audiences. Golliwogs are caricatures based on blackface portrayals in American minstrel shows. In these minstrel shows, white men would don blackface and perform a wide array of racial stereotypes through stock characters, presenting black Americans as lazy, uneducated, happy-go-lucky, etc. I was shocked by how prevalent these ugly caricatures were. Golliwogs were spilling off the pages of the Wood Collection, starring in many twentieth-century books involving toys and games. I decided to investigate the origin of the golliwog and explore the kinds of stories white authors are telling with this blackface iconography.

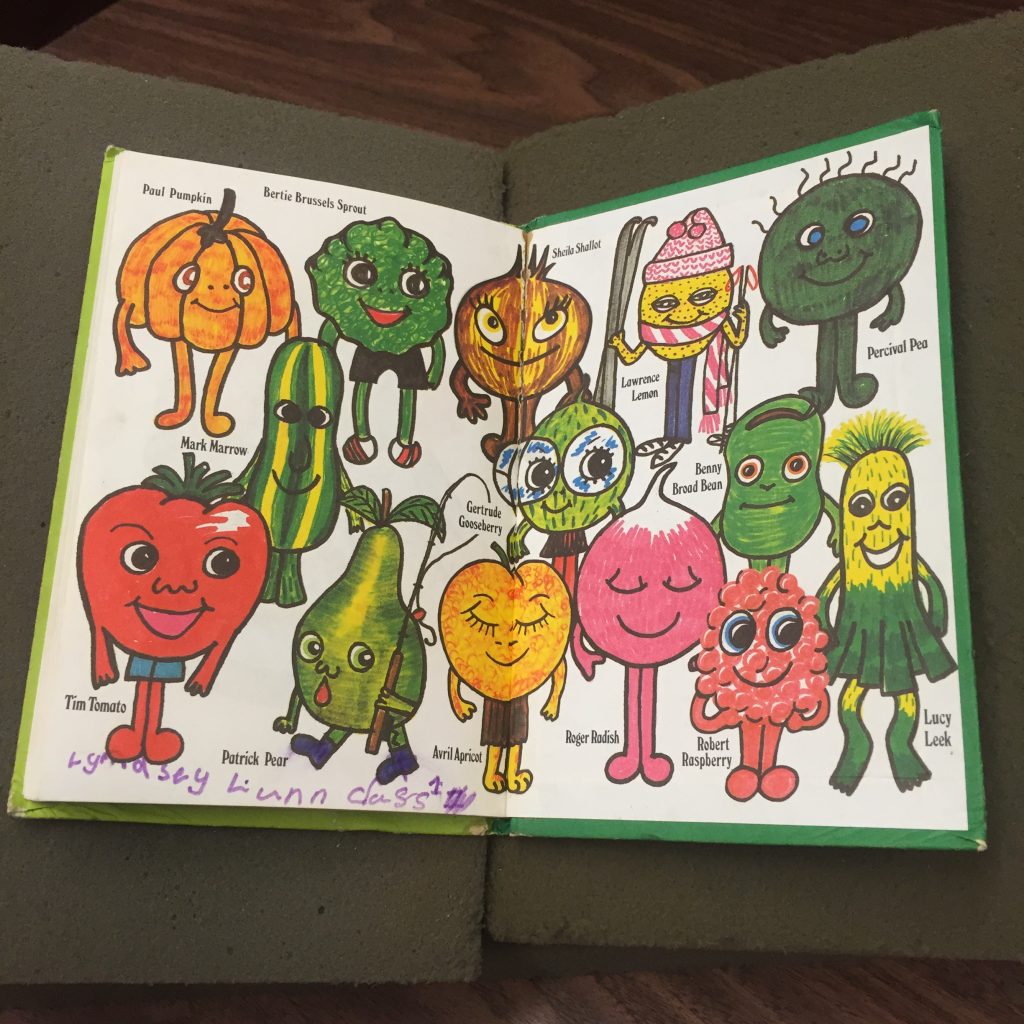

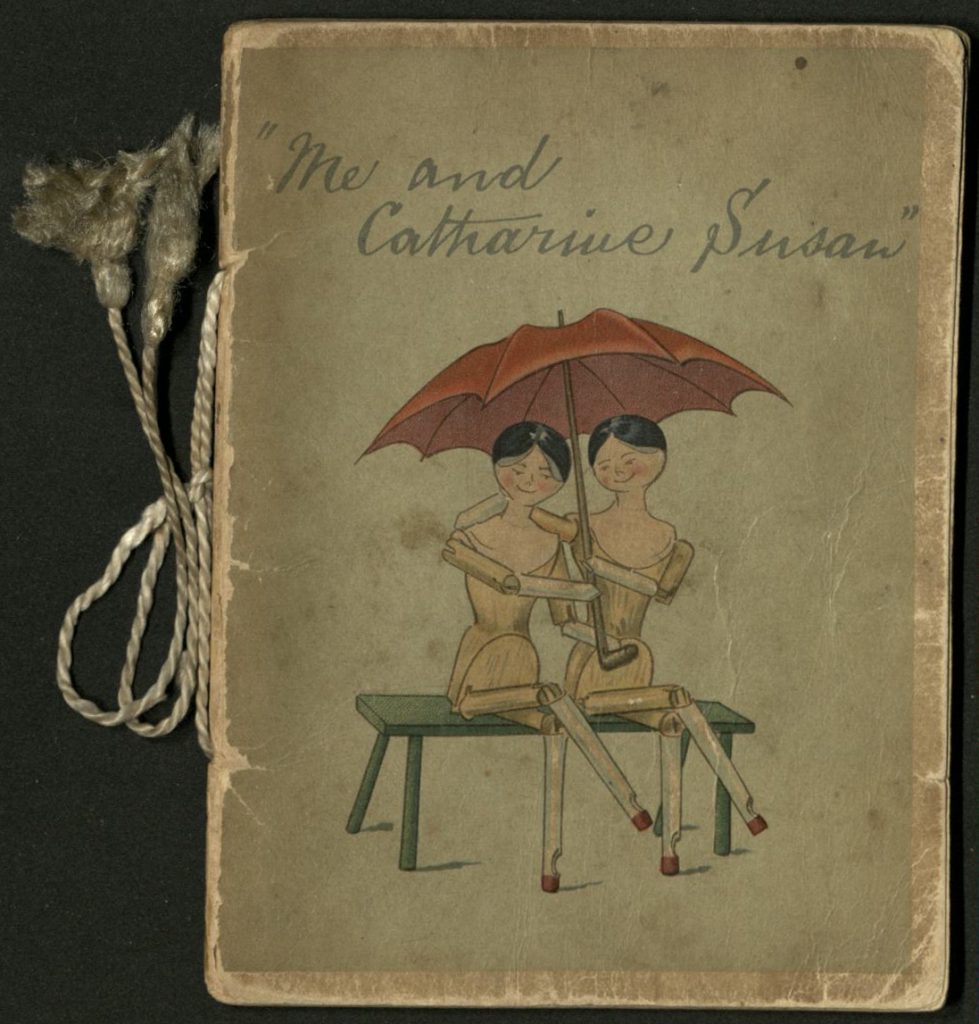

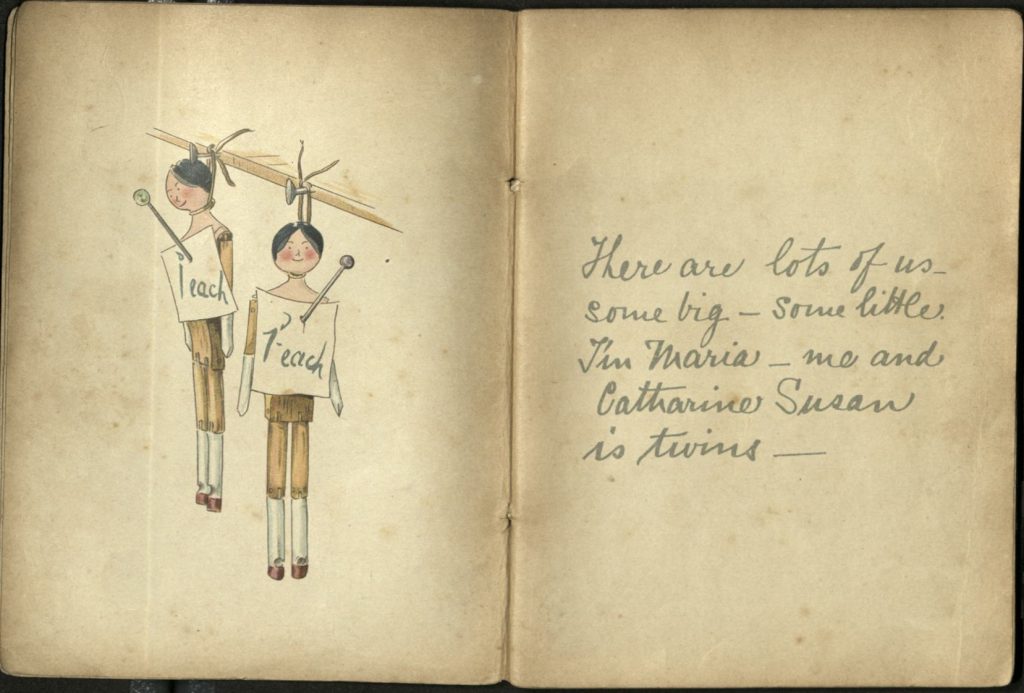

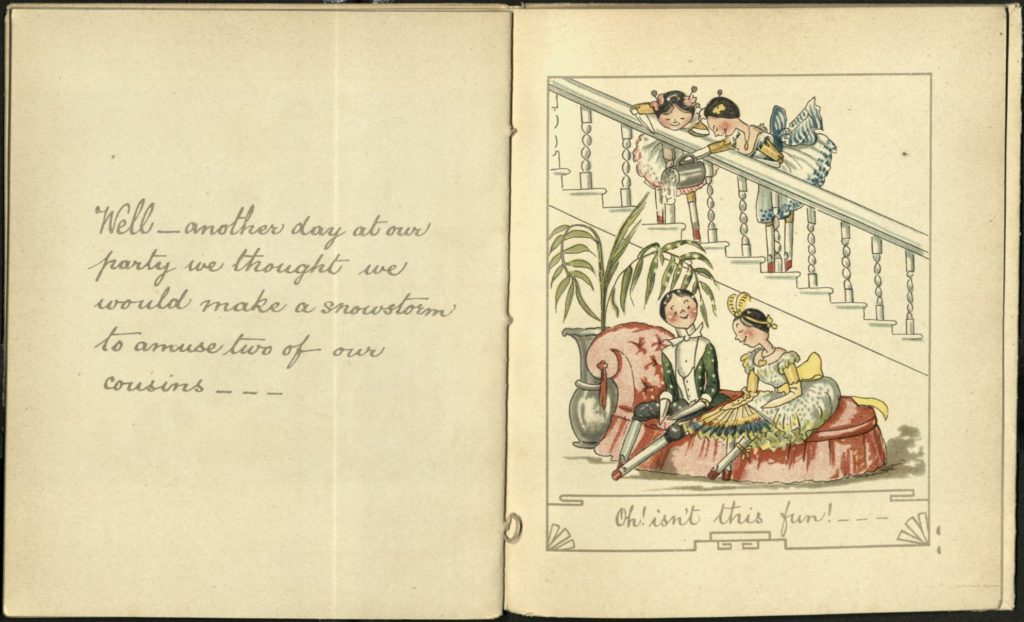

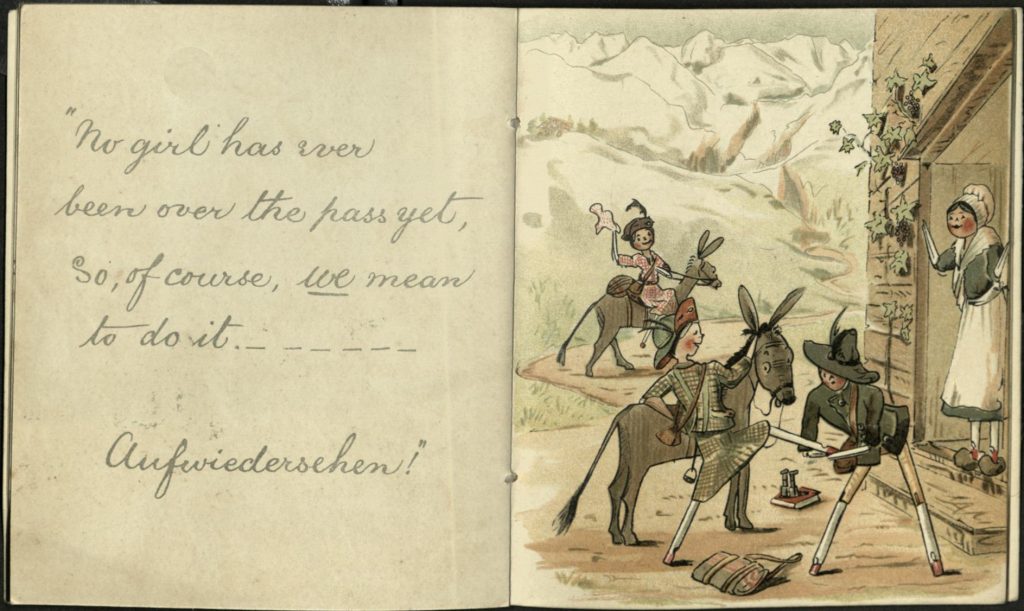

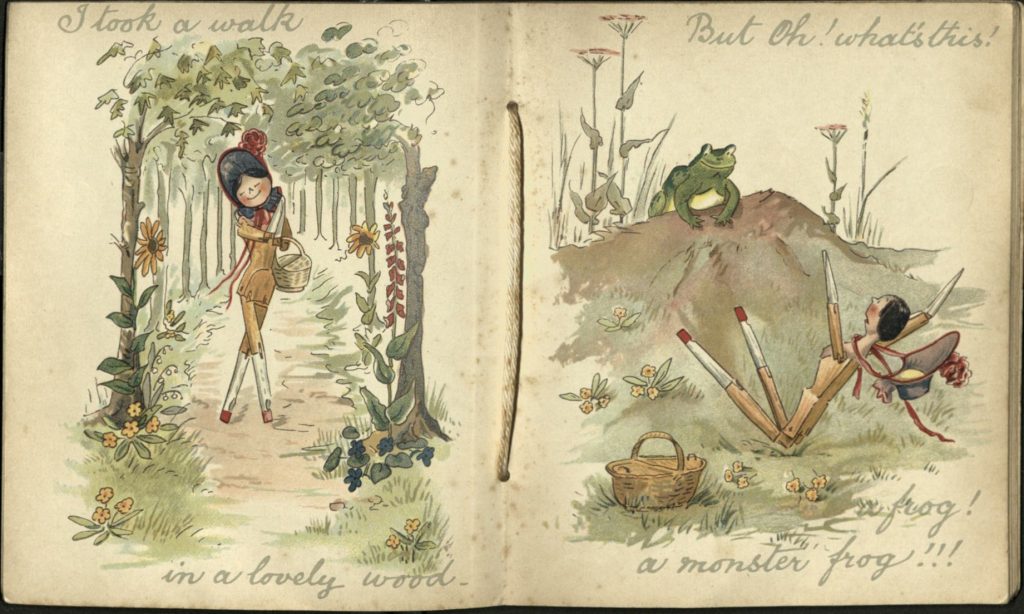

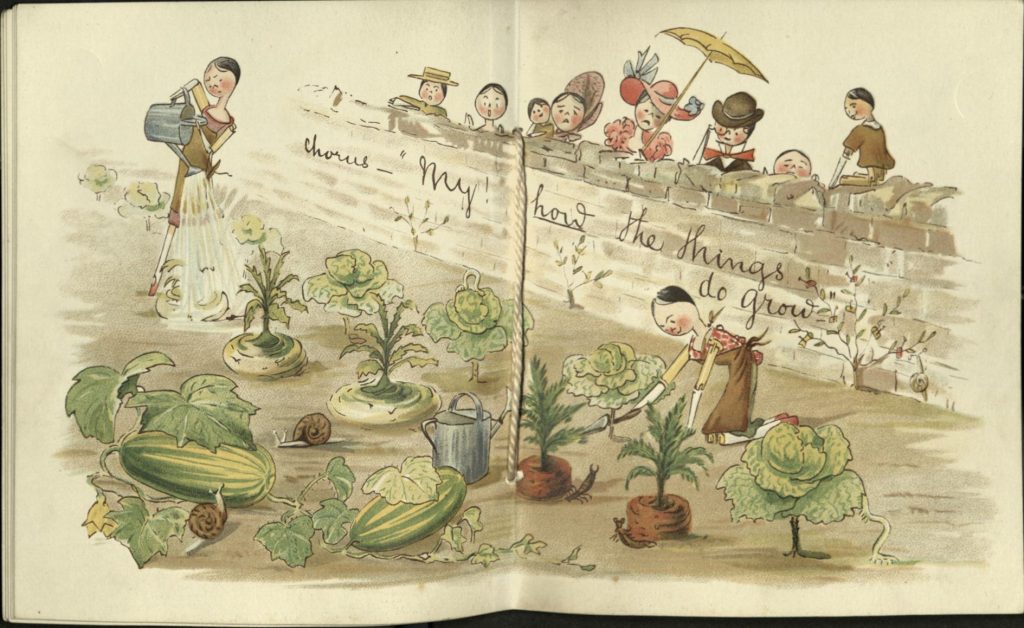

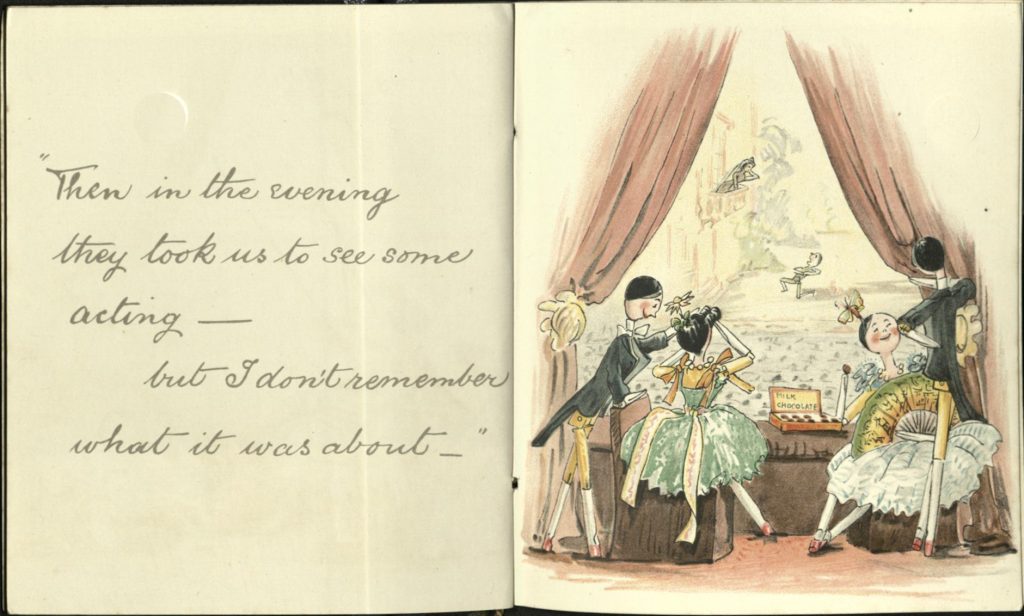

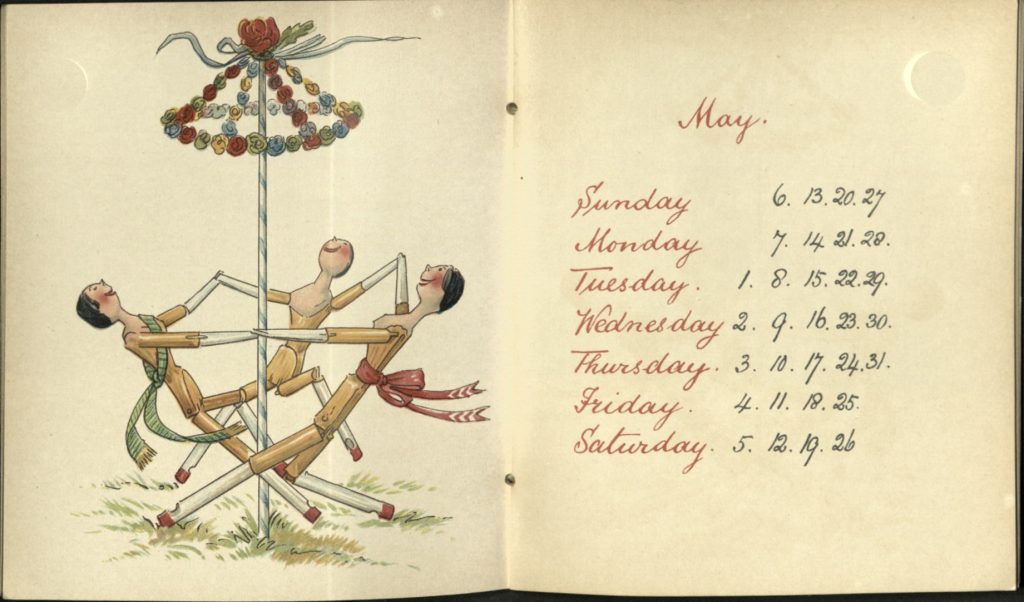

Golliwogs (originally a single character called “Golliwogg”) were created by the artist, Florence Kate Upton. After the death of her father, Upton pursued a career in children’s book illustration as a way to fund her art training. Inspired by a minstrel show doll her aunt pulled from the attic, Upton created her own blackface character called, “Golliwogg.” In the first book in the series The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls and a “Golliwogg” the Golliwogg is introduced, “Then all look round, as well they may—-To see a horrid sight! The blackest gnome—Stands there alone,—They scatter in their fright.” As this “gnome” is revealed to be brave and kind-hearted despite his “horrid” appearance, he continues on thirteen more adventures illustrated by Florence Kate Upton and penned by her mother, Bertha Upton. The Wood collection contains ten out of these thirteen books (many of them first editions). The series features Golliwogg and his two Dutch peg doll friends traveling to “exotic” lands and getting into trouble. Upton completed the series in 1909, but did not trademark her character, permitting golliwogs to be picked up by countless other authors, such as Enid Blyton (another prolific author within the collection). Following the popularity of the series, golliwogs were adapted into dolls. Although minstrel dolls existed beforehand, Golliwog dolls became massively popular in Great Britain, explaining their appearance in multiple books set in “Toyland.”

Golliwogs (originally a single character called “Golliwogg”) were created by the artist, Florence Kate Upton. After the death of her father, Upton pursued a career in children’s book illustration as a way to fund her art training. Inspired by a minstrel show doll her aunt pulled from the attic, Upton created her own blackface character called, “Golliwogg.” In the first book in the series The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls and a “Golliwogg” the Golliwogg is introduced, “Then all look round, as well they may—-To see a horrid sight! The blackest gnome—Stands there alone,—They scatter in their fright.” As this “gnome” is revealed to be brave and kind-hearted despite his “horrid” appearance, he continues on thirteen more adventures illustrated by Florence Kate Upton and penned by her mother, Bertha Upton. The Wood collection contains ten out of these thirteen books (many of them first editions). The series features Golliwogg and his two Dutch peg doll friends traveling to “exotic” lands and getting into trouble. Upton completed the series in 1909, but did not trademark her character, permitting golliwogs to be picked up by countless other authors, such as Enid Blyton (another prolific author within the collection). Following the popularity of the series, golliwogs were adapted into dolls. Although minstrel dolls existed beforehand, Golliwog dolls became massively popular in Great Britain, explaining their appearance in multiple books set in “Toyland.”

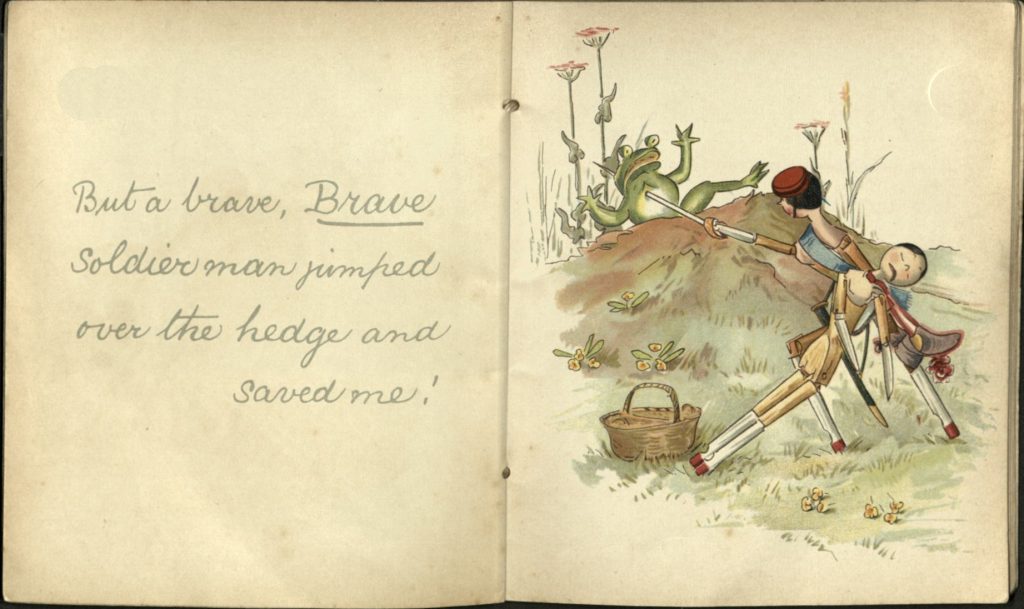

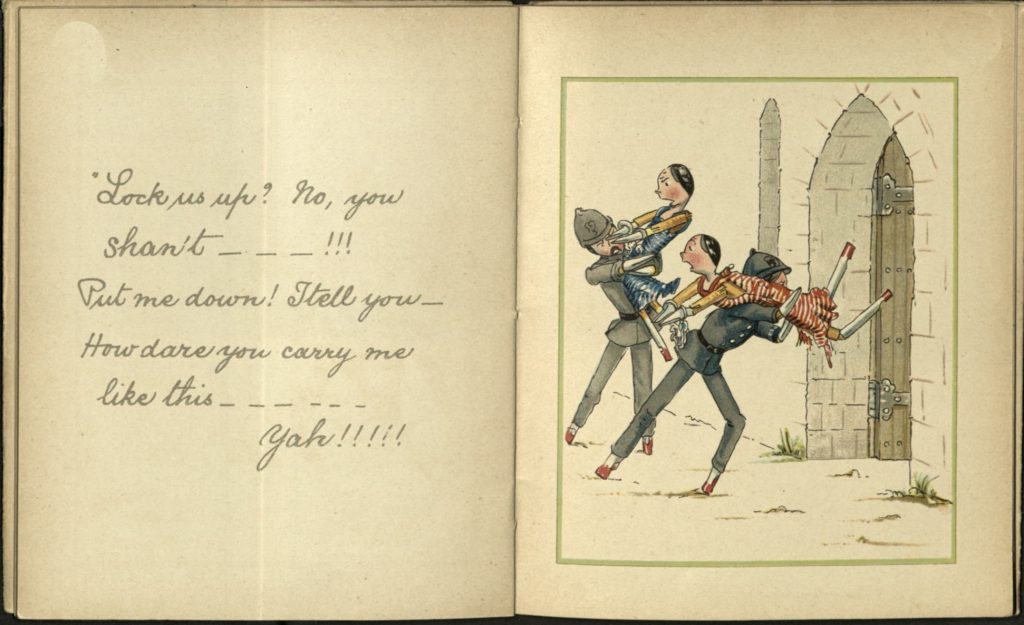

Golliwogg in Upton’s series is depicted as friendly, lovable, and adventurous. Based on the ugliness of her illustration and its roots in minstrel caricature, I was surprised to see how Golliwogg was written as the resourceful, courageous leader of the group of dolls (especially as the other dolls looked white). Despite the wide array of characters in blackface minstrel shows, Golliwogg’s personality doesn’t seem to match those defamatory stereotypes. In other writers’ depictions, golliwogs are less positively drawn, often becoming more mischievous and even monstrous as they were adapted into twentieth-century literature. However, I found that many people who grew up reading the original Golliwogg series greatly admired the character. For instance, Sir Kenneth Clarke defended him, saying that golliwogs were, “examples of chivalry, far more persuasive than the unconvincing knights of Arthurian legend.” Many children were touched by the virtues of Golliwogg’s character, but what did the Golliwogg truly represent?

Golliwogg in Upton’s series is depicted as friendly, lovable, and adventurous. Based on the ugliness of her illustration and its roots in minstrel caricature, I was surprised to see how Golliwogg was written as the resourceful, courageous leader of the group of dolls (especially as the other dolls looked white). Despite the wide array of characters in blackface minstrel shows, Golliwogg’s personality doesn’t seem to match those defamatory stereotypes. In other writers’ depictions, golliwogs are less positively drawn, often becoming more mischievous and even monstrous as they were adapted into twentieth-century literature. However, I found that many people who grew up reading the original Golliwogg series greatly admired the character. For instance, Sir Kenneth Clarke defended him, saying that golliwogs were, “examples of chivalry, far more persuasive than the unconvincing knights of Arthurian legend.” Many children were touched by the virtues of Golliwogg’s character, but what did the Golliwogg truly represent?

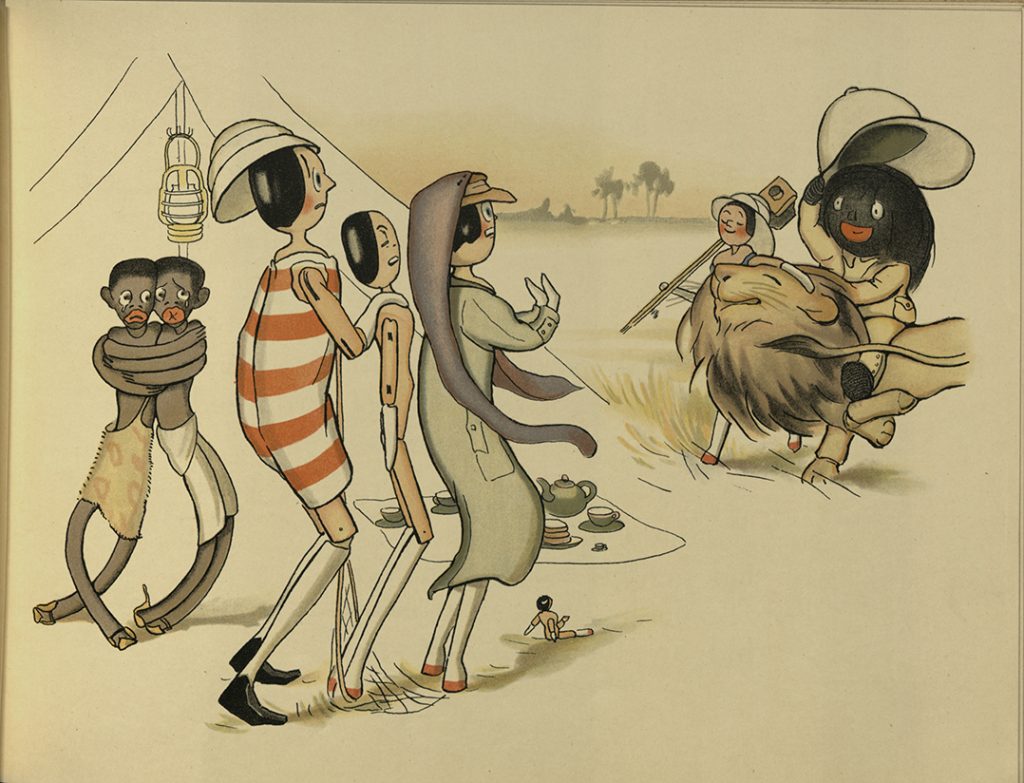

Reading through the Golliwogg series, I was left with the feeling that these books were enormously harmful, even as Golliwogg diverged from the American minstrel tradition. In Upton’s series, Black characters appear only as Golliwogg or as “primitive” African/Pacific Islander natives, who are often villainous and cannibalistic.

Reading through the Golliwogg series, I was left with the feeling that these books were enormously harmful, even as Golliwogg diverged from the American minstrel tradition. In Upton’s series, Black characters appear only as Golliwogg or as “primitive” African/Pacific Islander natives, who are often villainous and cannibalistic.

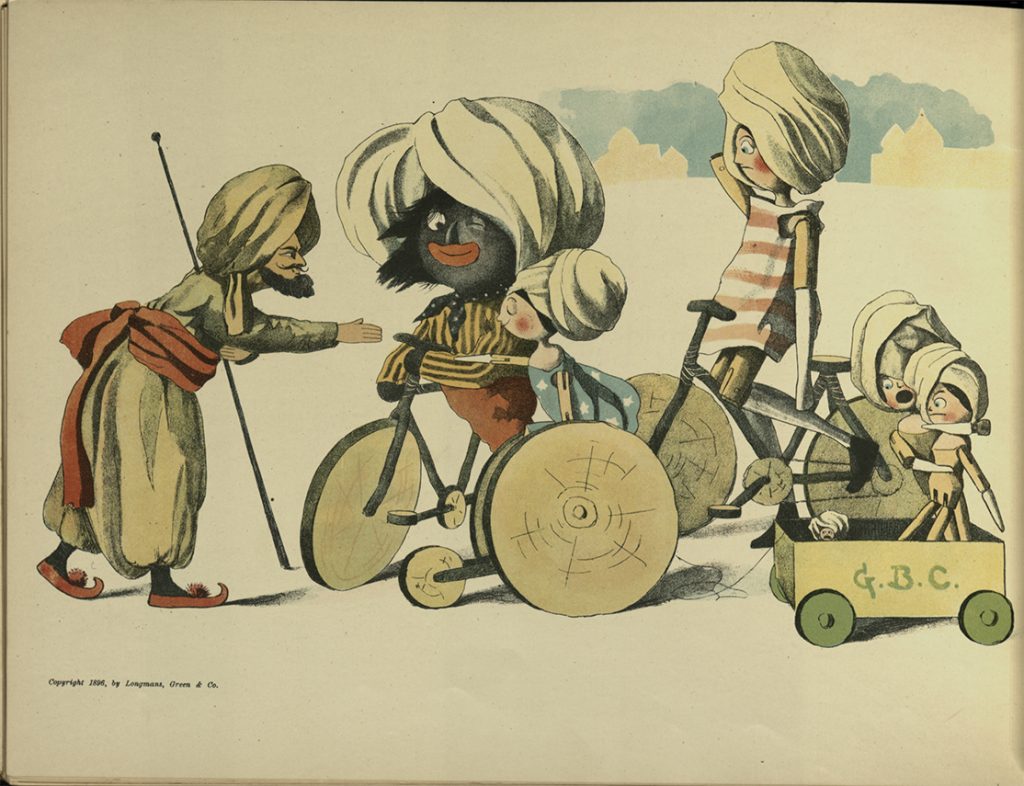

Through Golliwog’s worldly travels, Upton is able to create mocking caricatures of multiple ethnic groups, reducing them to their barest stereotypes. Unlike the white dolls, the features of Black characters are grotesquely exaggerated. Golliwogs are sometimes even drawn with paws, blatantly depicting them as nonhuman. Florence and Bertha Upton contort Blackness through their stories, limiting Black representation to villains and dolls. I feel that Upton’s cultural appropriation through the golliwogs dangerously warps her audience’s understanding of the Black community and Black experience. If generations of British children (both Black and white) were exposed to images of beautiful, angelic-looking white children holding up ugly black dolls, how does this shape their ideas of race, identity, and hierarchy? I was also struck by how Golliwogg’s adventures mimic imperialist exploits. His stories glorify war and exoticize other countries; at one point, Golliwogg even steals animals from the “African safari” for his personal zoo. Many children viewed Golliwogg as a hero, but perhaps he’s a hero within a skewed worldview.

Through Golliwog’s worldly travels, Upton is able to create mocking caricatures of multiple ethnic groups, reducing them to their barest stereotypes. Unlike the white dolls, the features of Black characters are grotesquely exaggerated. Golliwogs are sometimes even drawn with paws, blatantly depicting them as nonhuman. Florence and Bertha Upton contort Blackness through their stories, limiting Black representation to villains and dolls. I feel that Upton’s cultural appropriation through the golliwogs dangerously warps her audience’s understanding of the Black community and Black experience. If generations of British children (both Black and white) were exposed to images of beautiful, angelic-looking white children holding up ugly black dolls, how does this shape their ideas of race, identity, and hierarchy? I was also struck by how Golliwogg’s adventures mimic imperialist exploits. His stories glorify war and exoticize other countries; at one point, Golliwogg even steals animals from the “African safari” for his personal zoo. Many children viewed Golliwogg as a hero, but perhaps he’s a hero within a skewed worldview.

My exploration into the Golliwogg series has made me realize how important children’s literature is to determining our values and perceptions of the world. If Golliwogg fans were exposed to children’s literature written by Black writers instead, would they have grown up into different people, perhaps people with a more understanding, open-minded perspective? One very immediate consequence of golliwogs is the emergence of the racial slur, “wog,” which many people believe stemmed from the series. The ramifications of Golliwogg and characters like him are real and this experience has made me wonder what kinds of prejudice exist within me because of what I was read to as a child.

My exploration into the Golliwogg series has made me realize how important children’s literature is to determining our values and perceptions of the world. If Golliwogg fans were exposed to children’s literature written by Black writers instead, would they have grown up into different people, perhaps people with a more understanding, open-minded perspective? One very immediate consequence of golliwogs is the emergence of the racial slur, “wog,” which many people believe stemmed from the series. The ramifications of Golliwogg and characters like him are real and this experience has made me wonder what kinds of prejudice exist within me because of what I was read to as a child.

Isabella Nugent (BMC 2018) has been working this summer in Special Collections. Among many other tasks, she has unpacked, cleaned, sorted and inventoried books from the Ellery Yale Wood Collection.

Isabella Nugent (BMC 2018) has been working this summer in Special Collections. Among many other tasks, she has unpacked, cleaned, sorted and inventoried books from the Ellery Yale Wood Collection.