“A is for Apple. B is for Ball,” we say these days. But for two hundred years, English children learning the alphabet grappled instead with apple pie, greed, and interpersonal conflict. Hebrew, Greek and Latin sources provide ancient abecedarian poetry and texts, where the first letter of each line – or verse or stanza – starts with a letter in alphabetical order. Psalm 119 (“Blessed are the undefiled in the way, who walk in the law of the LORD. ” KJV) is abecedarian in Hebrew. St. Augustine’s Psalmus contra partem Donati sets the stanzas in alphabetical order, in Latin. Even Chaucer wrote a carmen secundum ordinem litterarum alphabeti, in English, in honor of the Virgin Mary.

Hebrew, Greek and Latin sources provide ancient abecedarian poetry and texts, where the first letter of each line – or verse or stanza – starts with a letter in alphabetical order. Psalm 119 (“Blessed are the undefiled in the way, who walk in the law of the LORD. ” KJV) is abecedarian in Hebrew. St. Augustine’s Psalmus contra partem Donati sets the stanzas in alphabetical order, in Latin. Even Chaucer wrote a carmen secundum ordinem litterarum alphabeti, in English, in honor of the Virgin Mary.

No one knows when the first ABC poem meant for the youngest readers was created, but Apple Pie was current in England in the 17th century. John Eachard, satirist and doctor of divinity, published a humorous criticism of sermons in the Church in 1671. While abusing preachers who stretch their sermons by elaborating on each letter in a word (REPENT – Readily Earnestly, Presently, Effectually…) he says, “And also why not A Apple-pasty, B bak’d it, C cut it, D divided it, E eat it, F fought for it, G got it, &c. ?” The poem next appears in print in 1743, when it was included in The Child’s New Play-thing, a spelling book that began with several alphabets and ABC poems. It was printed frequently after that in the frenzy of the new market for children’s books.

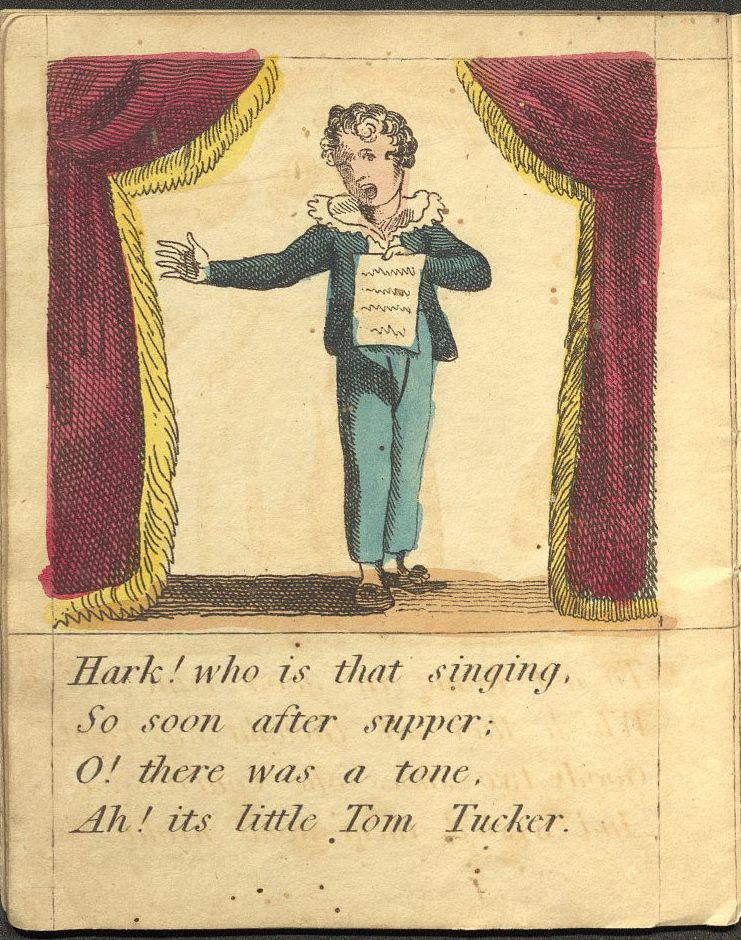

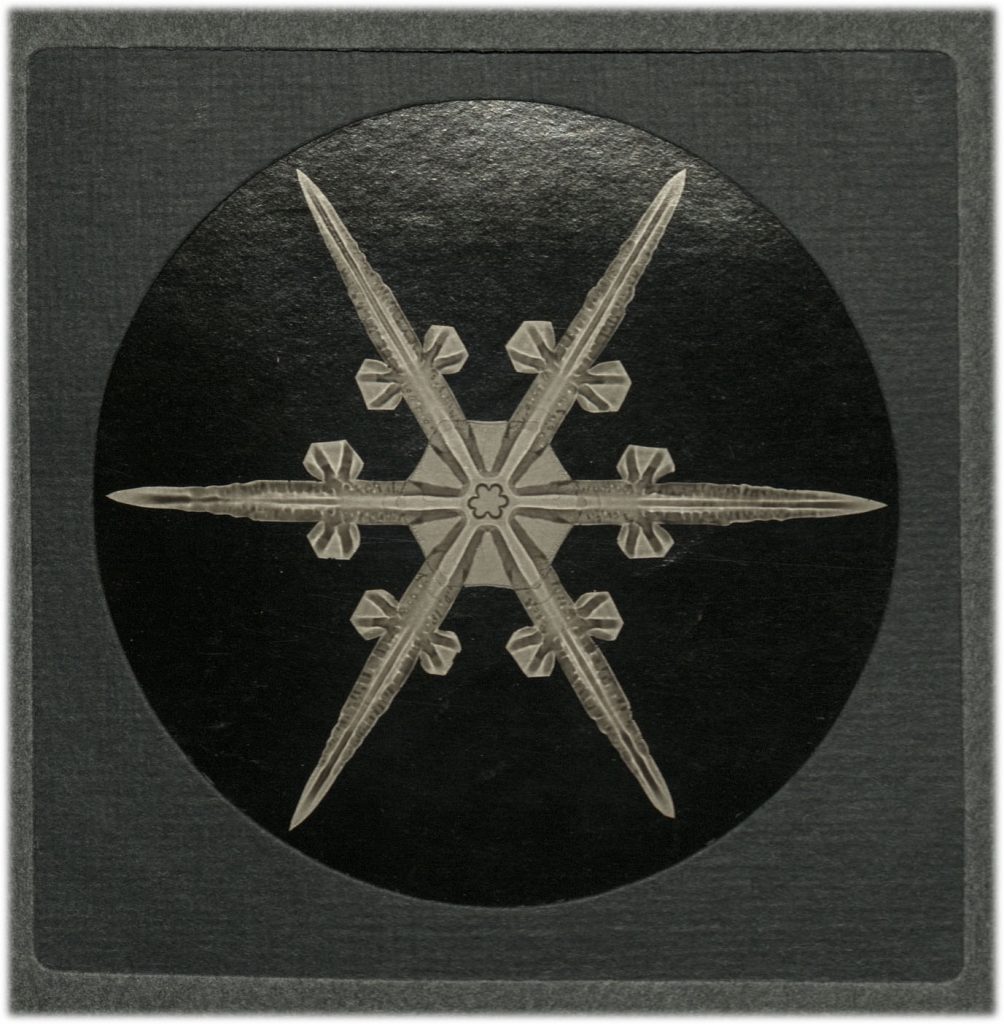

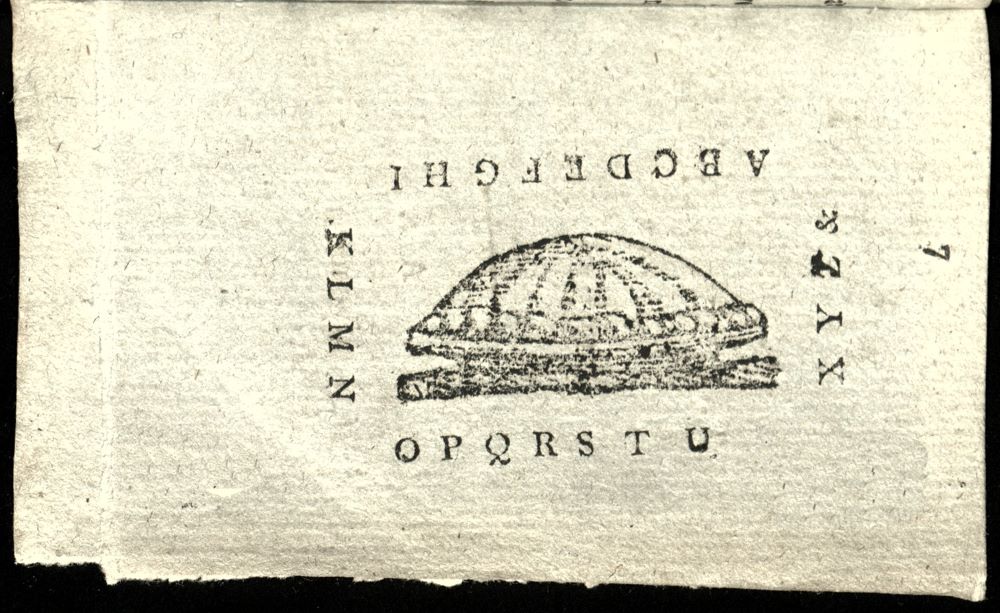

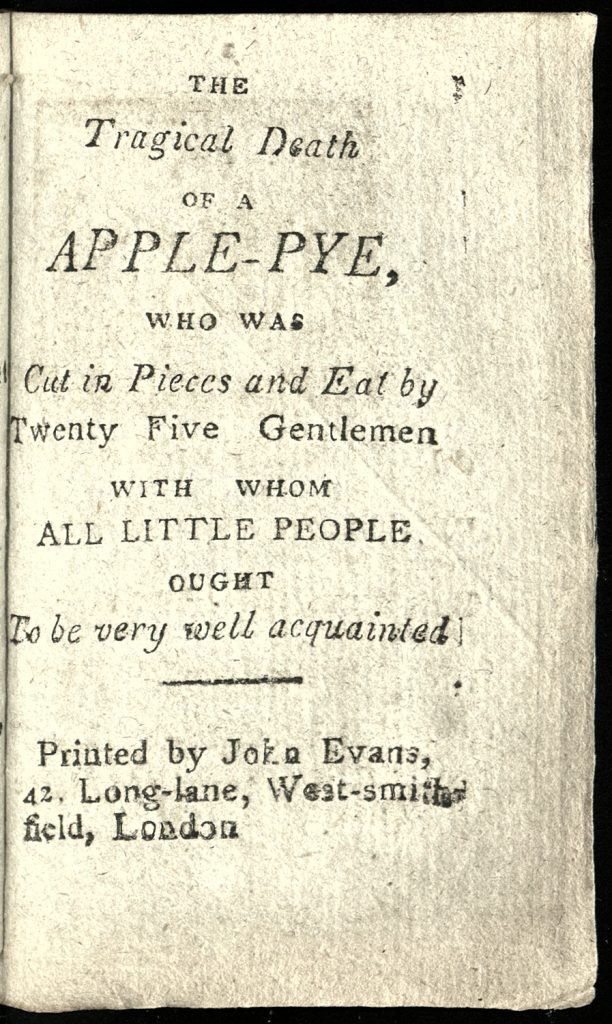

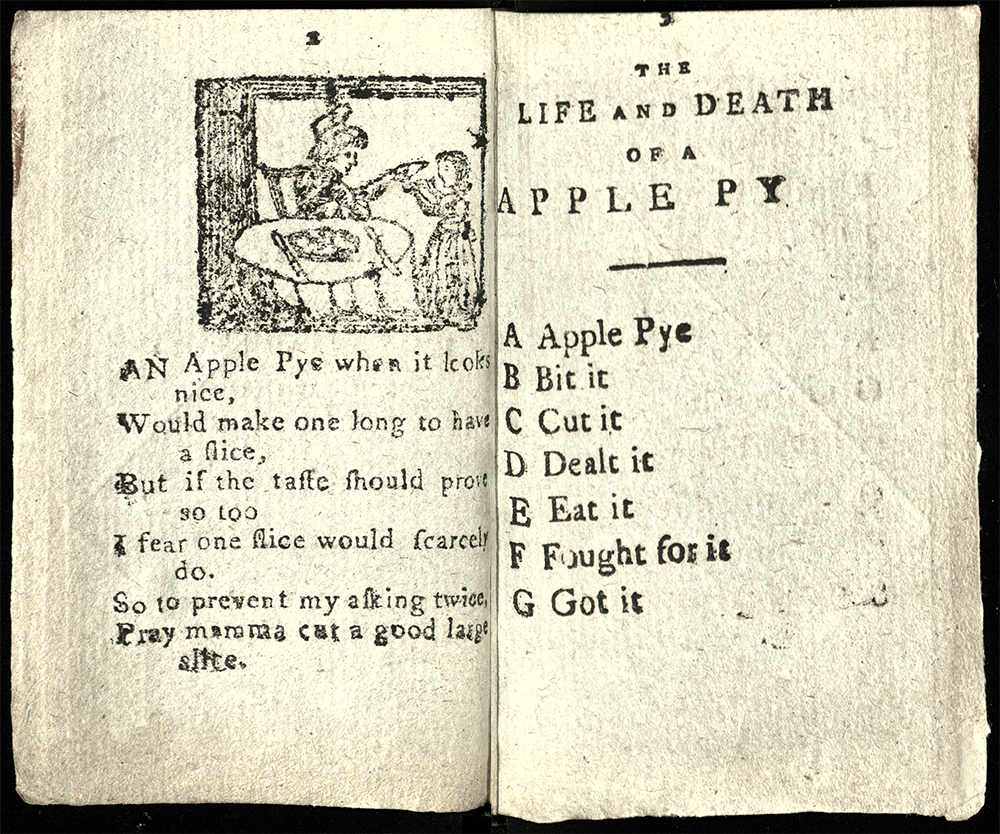

Many of those “books” were the tiny publications called chapbooks – a single sheet of paper printed on both sides, and folded to make a little sixteen-page pamphlet smaller than the palm of your hand. Our Apple Pye is one of these, roughly 3 1/2 inches tall and 2 1/4 inches wide. It was published around 1800 (it is undated) and the fragile miniature might not have survived, except that it was bound with 14 other chapbooks early on, probably in the eighteen teens.

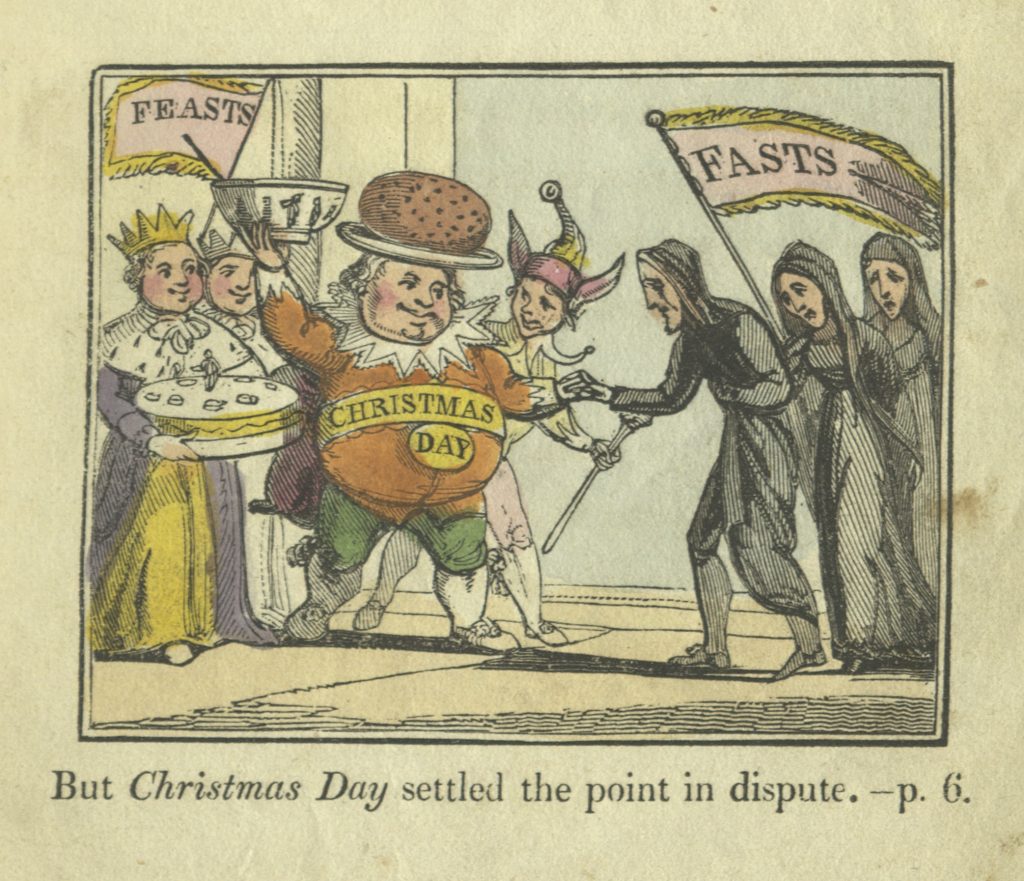

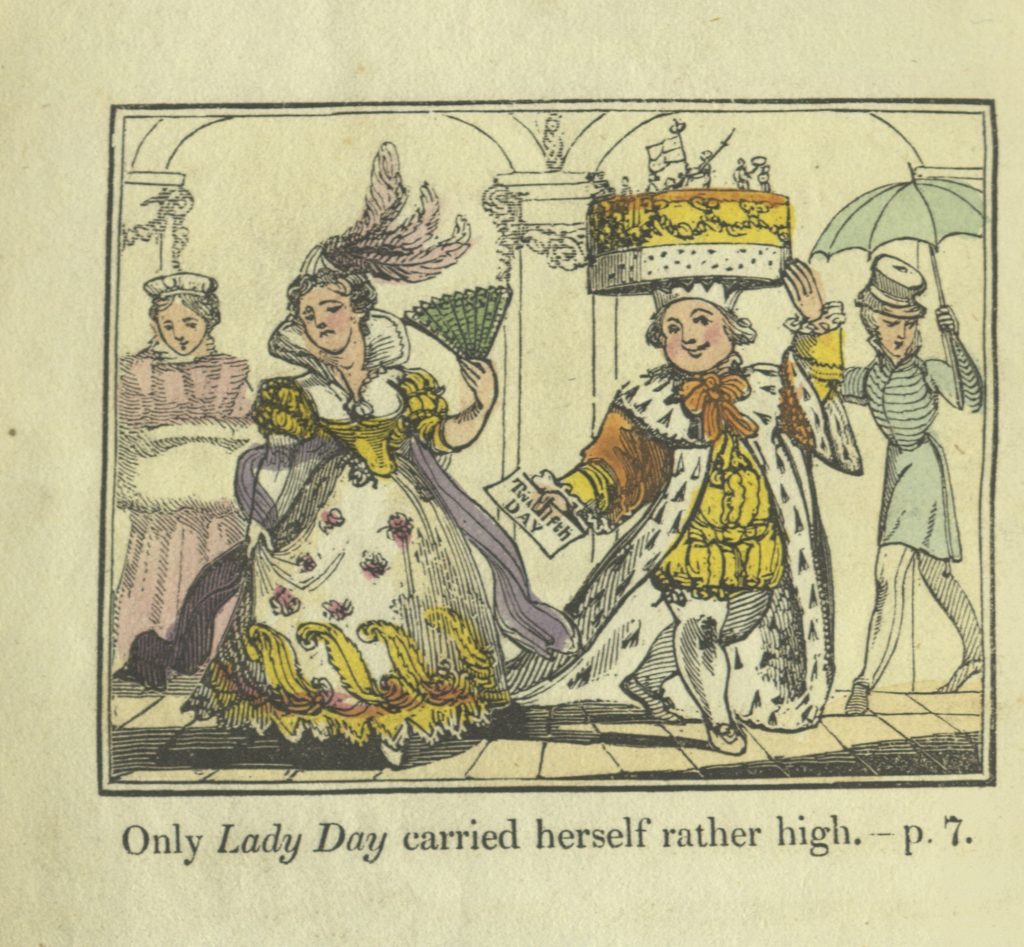

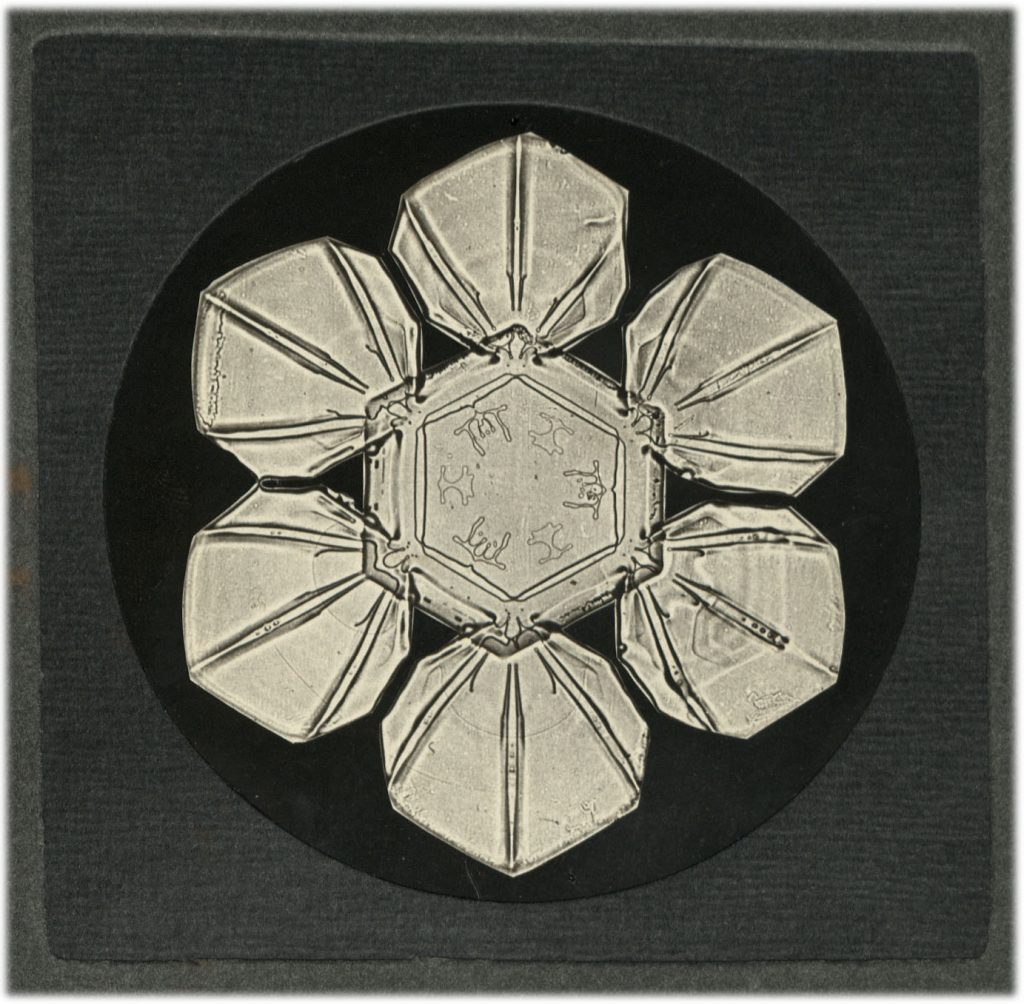

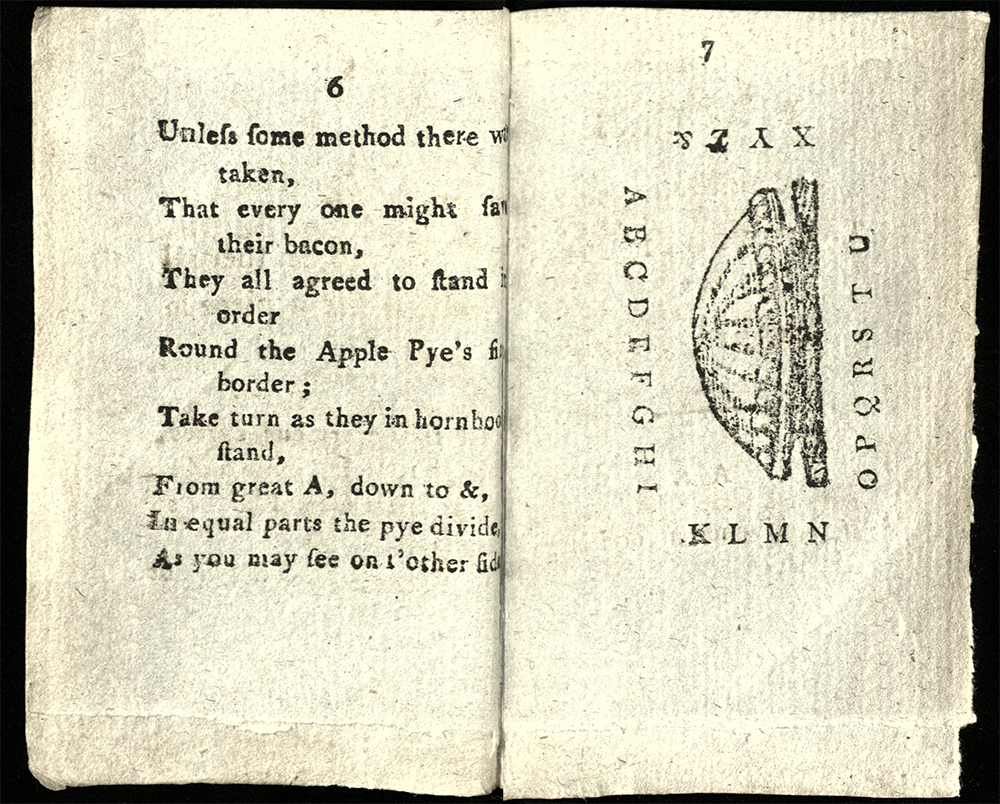

The book includes two alphabet poems, and it begins with a woodcut and a bit of doggerel where a canny child demands a large slice of pie, to save the trouble of asking for a second. The poem proper (The Tragical Death of A Apple-Pye, Who Was Cut in Pieces and Eat by Twenty Five Gentlemen) then begins, and each letter takes some action towards A, the apple pie itself. There is the usual trouble with choosing appropriate words at the end of the alphabet, and X, Y, and Z have to collaborate with Ampersand. The “Twenty-five gentlemen” realize there may not be enough to go around, so they agree to stand in order around the pie and take turns.

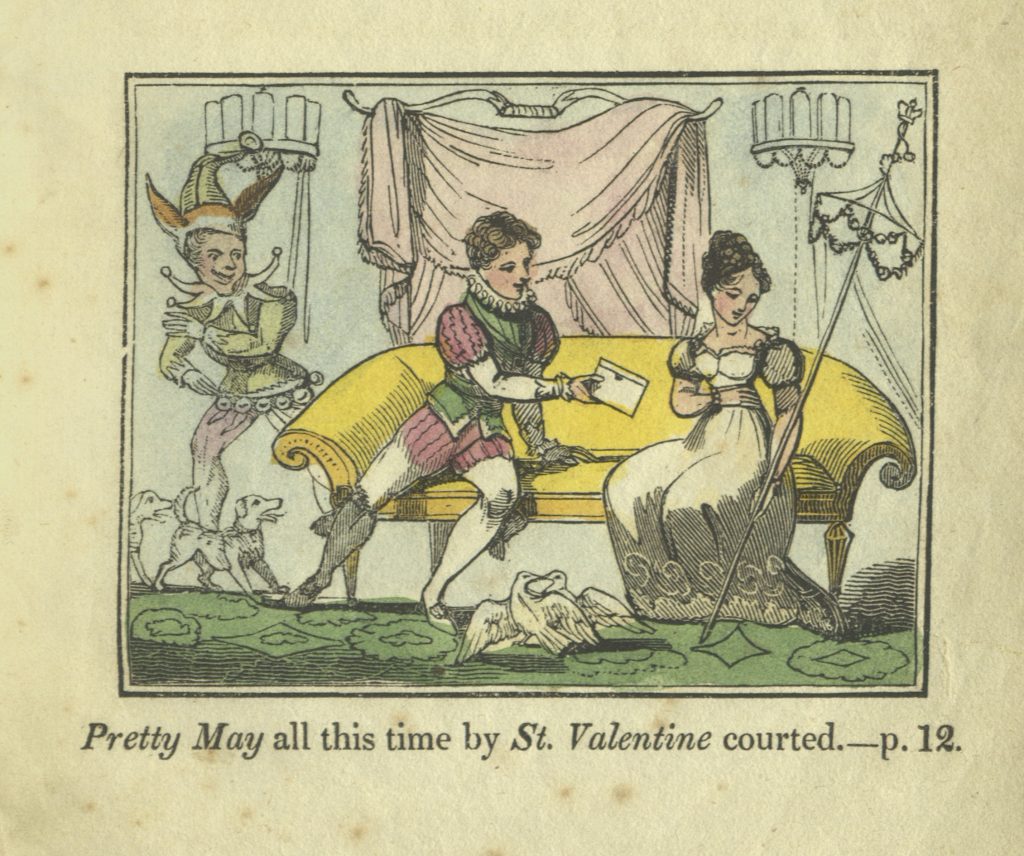

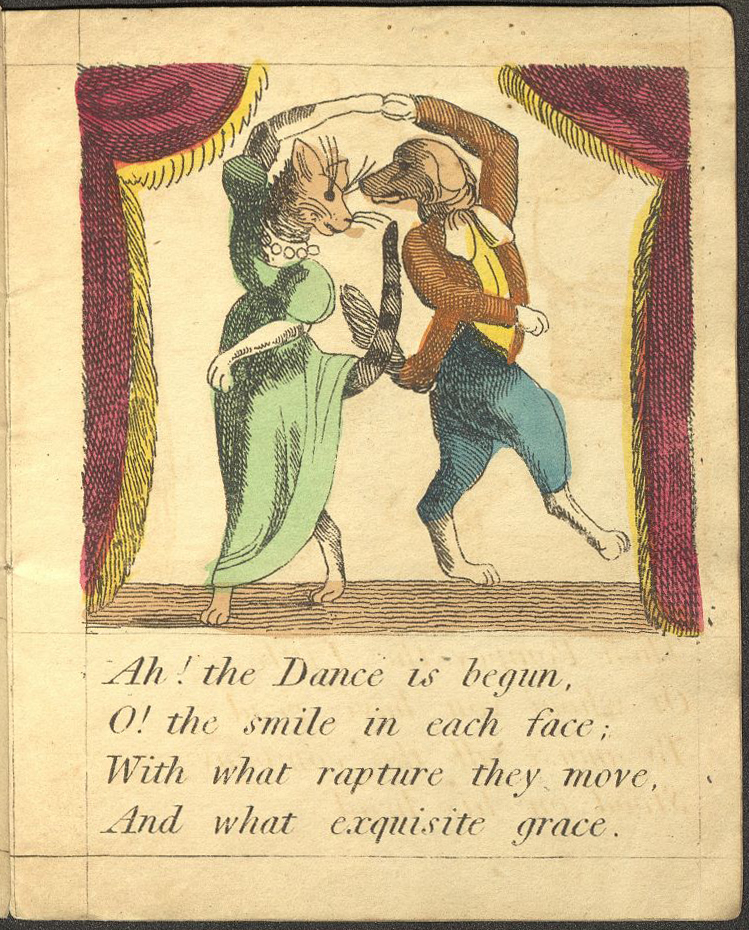

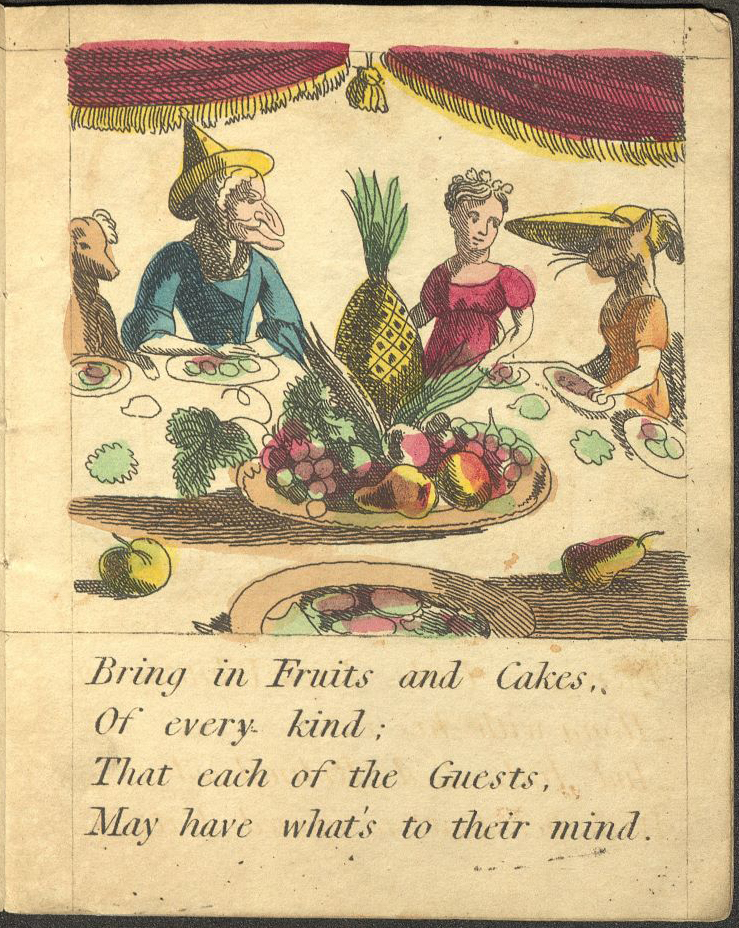

There is the usual trouble with choosing appropriate words at the end of the alphabet, and X, Y, and Z have to collaborate with Ampersand. The “Twenty-five gentlemen” realize there may not be enough to go around, so they agree to stand in order around the pie and take turns. But they do not then all use their nicest manners to ensure a fair distribution of the meal. The second alphabet poem, A Curious Discourse that Passed Between the Twenty-five Letters at Dinner-Time, starts with A, like the little girl in the opening verse, asking for “a good, large slice.”

But they do not then all use their nicest manners to ensure a fair distribution of the meal. The second alphabet poem, A Curious Discourse that Passed Between the Twenty-five Letters at Dinner-Time, starts with A, like the little girl in the opening verse, asking for “a good, large slice.” Every letter has its preferences, although most of them just want a lot of pie.

Every letter has its preferences, although most of them just want a lot of pie. Predictably, by the time it is Y’s turn, he eats the last piece, and Z and Ampersand have to lick the dish. John Evans, the printer/publisher, then inserted an advertisement for his other books for “little readers,” complete with his shop address.

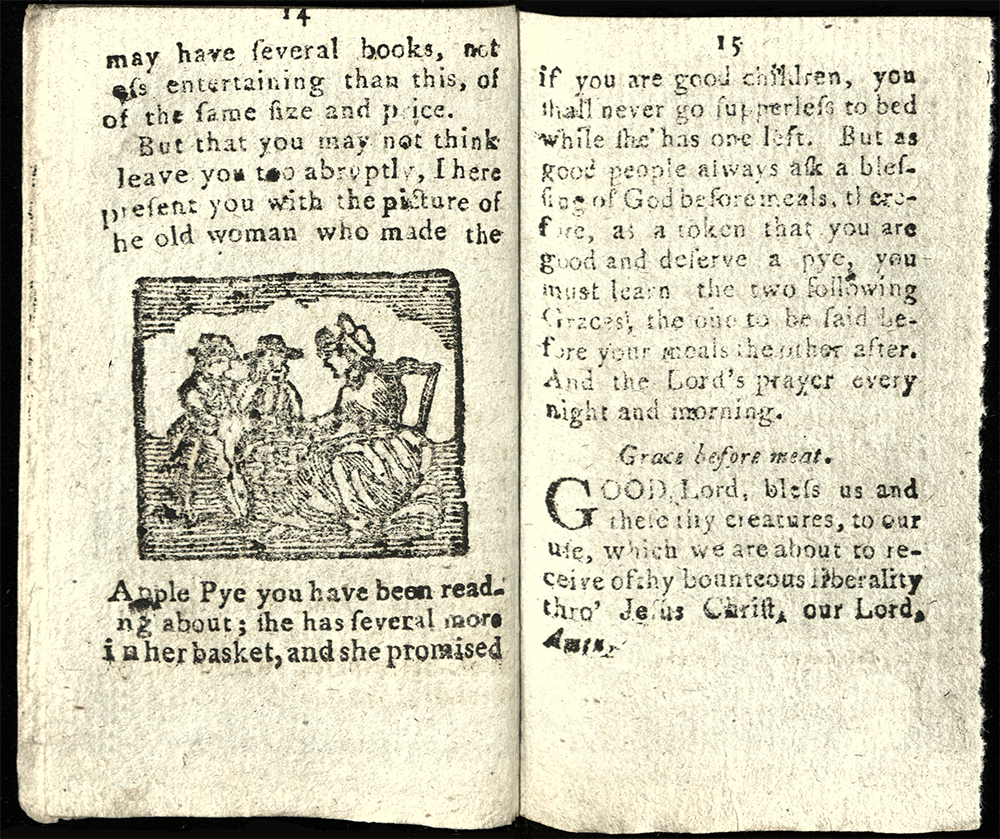

Predictably, by the time it is Y’s turn, he eats the last piece, and Z and Ampersand have to lick the dish. John Evans, the printer/publisher, then inserted an advertisement for his other books for “little readers,” complete with his shop address. Evans still had three small pages to fill, so he added a woodcut of the imaginary old woman who made the pie in the poem, and stated she would supply a similar treat to good children. But since good people always pray before meals, he included a grace for the children to learn – to demonstrate that they deserved a pie. On the final page, he printed a postprandial grace and the Lord’s Prayer.

Evans still had three small pages to fill, so he added a woodcut of the imaginary old woman who made the pie in the poem, and stated she would supply a similar treat to good children. But since good people always pray before meals, he included a grace for the children to learn – to demonstrate that they deserved a pie. On the final page, he printed a postprandial grace and the Lord’s Prayer. Our copy of The Tragical Death is part of the Ellery Yale Wood Collection of Books for Young Readers. It has been digitized and is available for your perusal on the Internet Archive.

Our copy of The Tragical Death is part of the Ellery Yale Wood Collection of Books for Young Readers. It has been digitized and is available for your perusal on the Internet Archive.

The Tragical Death of a Apple-Pye, Who Was Cut in Pieces and Eat by Twenty Five Gentlemen: With Whom All Little People Ought to Be Very Well Acquainted. London: Printed by John Evans, 42, Long-lane, West-smithfield, c.1800.

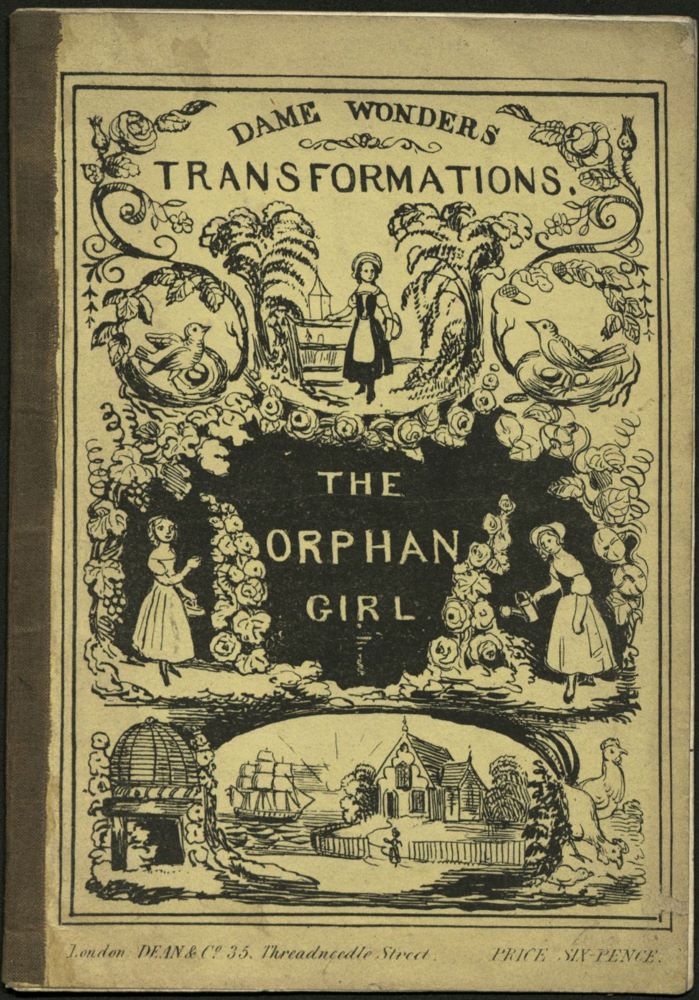

With the continuing closure of the Library, we are blogging regularly about books from the exhibition, The Girl’s Own Book. Please subscribe or check back here, or follow us on Facebook for notices of new blogs.

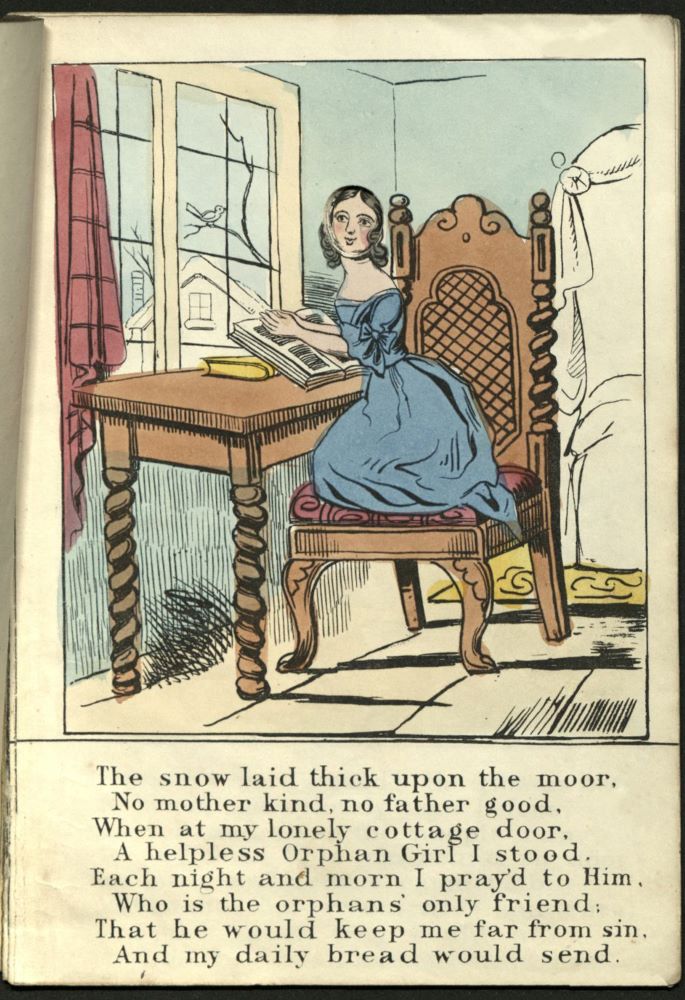

As a result of her earnest piety, her garden provides abundant bouquets which she sells to the wealthy.

As a result of her earnest piety, her garden provides abundant bouquets which she sells to the wealthy.