“There has never been anything real about my life over here. I can’t believe that it is I who am seeing it with my eyes, living in something that is a reality and not a dream. It worries me sometimes for I am afraid it will disappear out of my memory like a dream and I just don’t know what to do to hold on to it” (84-5). This is one of Margaret Hall’s more poignant moments as she reflects on her service for the Red Cross during World War I. Her experience so strongly affected her that she compiled her correspondence and photographs into a typed bound manuscript: Letters and Photographs from the Battle Country, 1918 and 1919 . I had the opportunity to read an original copy. As a recently graduated history major/nerd, I was excited to actually hold the historic manuscript and learn about WWI through the eyes of Margaret Hall.

“There has never been anything real about my life over here. I can’t believe that it is I who am seeing it with my eyes, living in something that is a reality and not a dream. It worries me sometimes for I am afraid it will disappear out of my memory like a dream and I just don’t know what to do to hold on to it” (84-5). This is one of Margaret Hall’s more poignant moments as she reflects on her service for the Red Cross during World War I. Her experience so strongly affected her that she compiled her correspondence and photographs into a typed bound manuscript: Letters and Photographs from the Battle Country, 1918 and 1919 . I had the opportunity to read an original copy. As a recently graduated history major/nerd, I was excited to actually hold the historic manuscript and learn about WWI through the eyes of Margaret Hall.

July 28, 2014 marks the 100th anniversary of the beginning of the Great War, so it is appropriate that the Massachusetts Historical Society currently has an exhibition, “Letters and Photographs From the Battle Country: Massachusetts Women in the First World War,” featuring Hall’s writings. There are only four known copies of Margaret Hall’s book. Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, the Massachusetts Historical Society and the Cohasset Historical Society each own one. World War I does not occupy a particularly large space in US popular culture, especially when compared to World War II. Movies like Saving Private Ryan, Schindler’s List or Patton are widely considered classic American films. Speaking for my generation, our little knowledge of World War I comes from the novel, All Quiet on the Western Front, primarily because it is required reading in many high schools. I have always thought WWI fascinating as its own historical moment, not just simply a precursor to WWII.

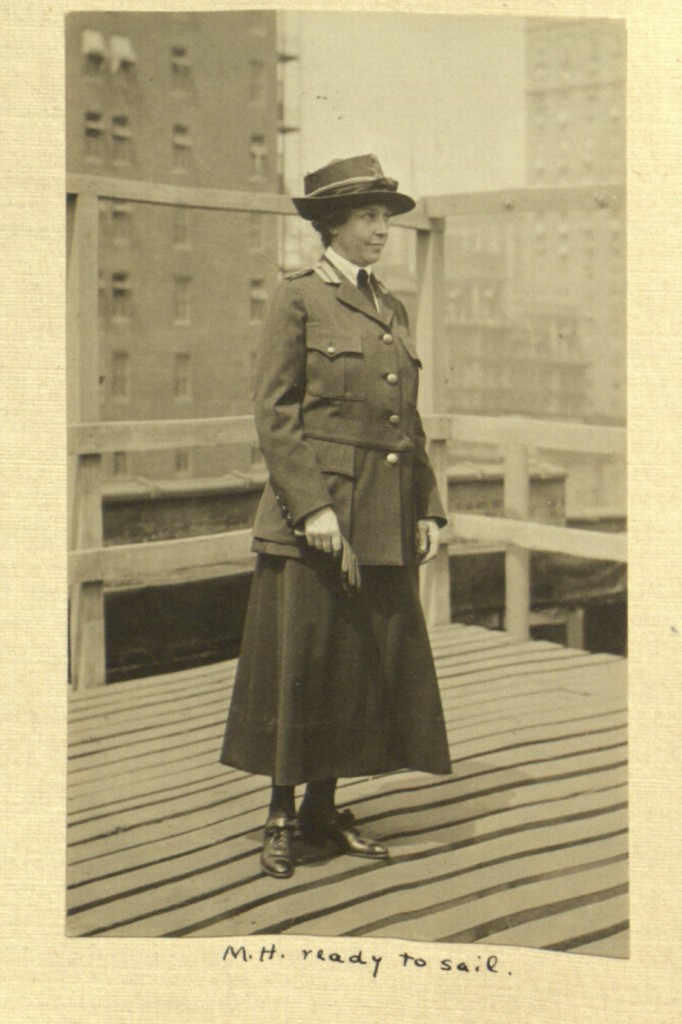

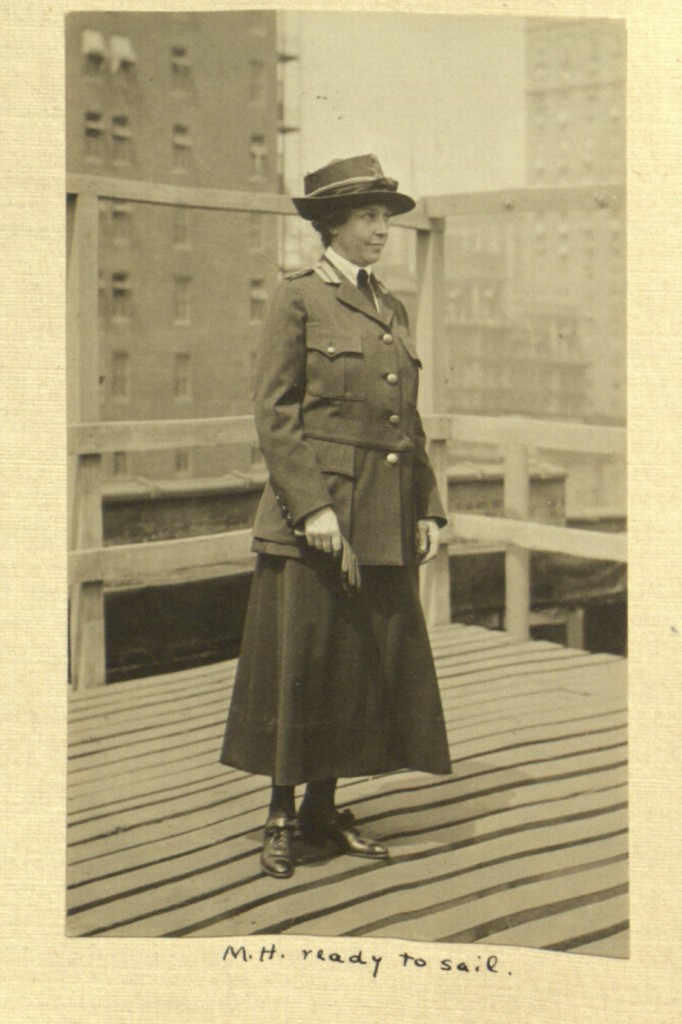

Margaret Hall graduated from Bryn Mawr College in 1899 with a degree in history. She came from a relatively well-to-do family in Boston, Massachusetts. In 1915, she helped organize nationwide marches for women’s suffrage. In 1917, according to Bryn Mawr’s Alumnae Quarterly, she traveled to Cuba and the Isle of Pines and later that year started her own farm. Then, on August 23, 1918 Hall sailed across the submarine strewn Atlantic Ocean into the deadly combat zone of Marne, France. I was curious to know why she did this but unfortunately, she does not expand upon what precisely influenced her decision. Perhaps she felt a sense of duty or wanted adventure. Of course, we will never know but it is certain that she was a strong-willed woman who was not intimidated by the unknown.

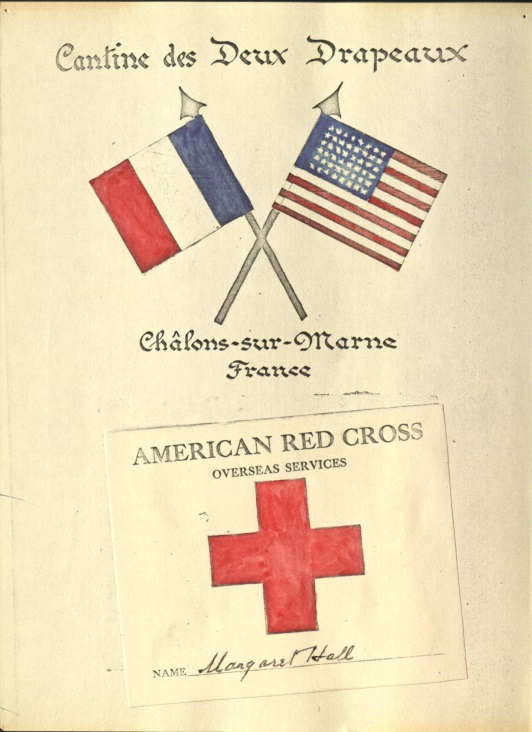

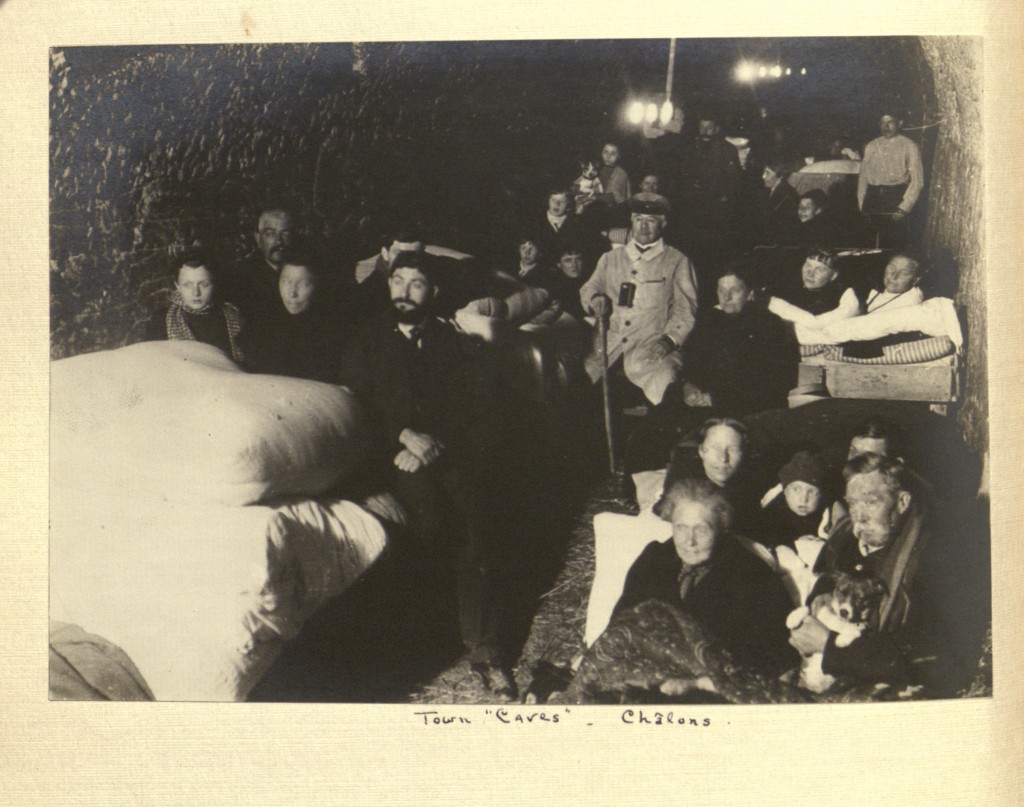

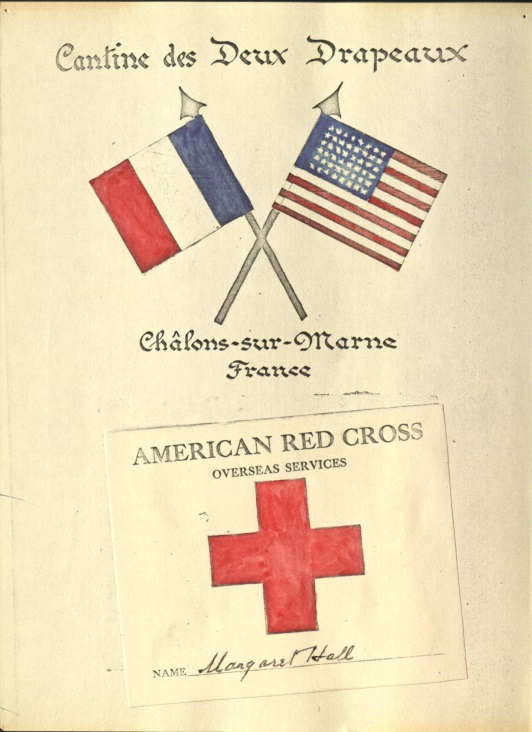

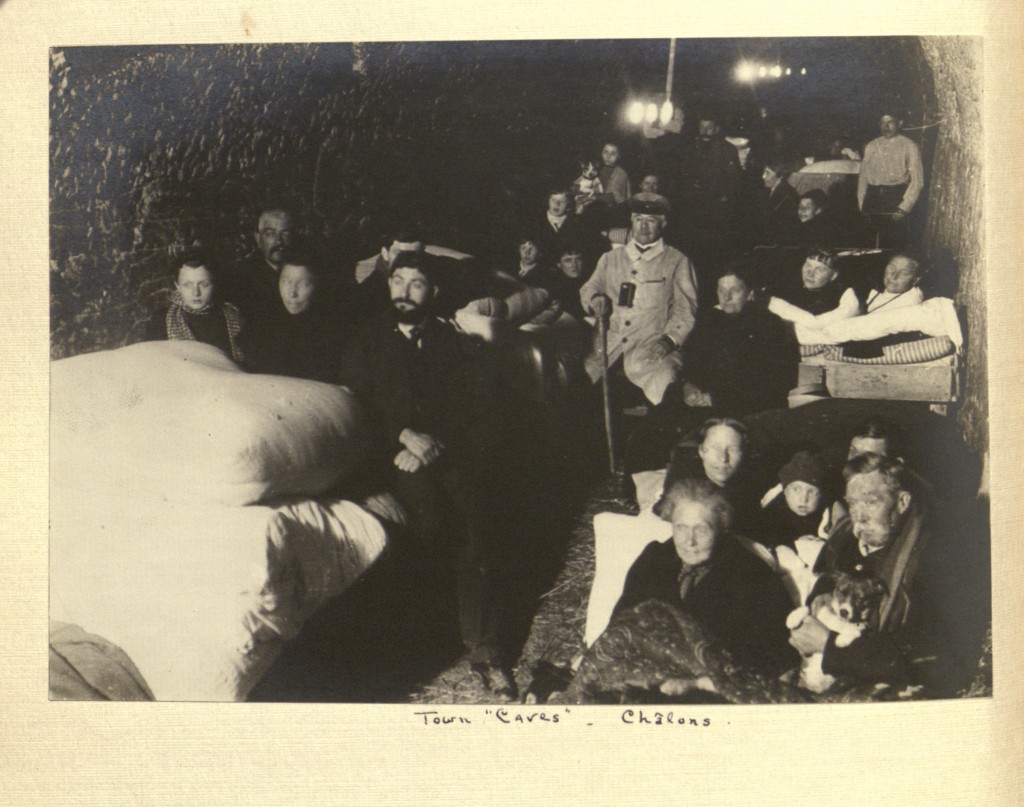

Once Margaret arrived in Paris, she was assigned to a desk job that required her to read casualty reports and letters. Then she would have to write families “about the boys’ last words, what they did and said, their funerals, etc.” (18). Hall found this incredibly depressing and desired to work at a canteen near the frontlines: “I have no hopes of getting near the front. The Red Cross does not send women near, they tell me…Salvation Army is what I want and I wish to goodness I had tried for it.” (17) But, like a true Mawrter, she persisted and ultimately was assigned to the Chalons-sur-Marne, “Cantine des Deux Drapeaux.” This Red Cross canteen in the St. Mihiel sector was literally on the front lines of World War 1 and Hall arrived just in time for the last major battle of the war. She and others at the canteen often had to take cover in the local abris, underground caves. Near the end of the war, Hall writes on November 1, 1918: “The guns are banging away at the front. It is much farther away, but we can still hear them, and they always disturb one’s nervous system. We’ve got the hardest part of the line near us, where there is terrific fighting and terrific mortality. Everyone from the front says the same thing, that it is awful up there. Think of being so near to it that we can hear it thundering on!” (83-4). The fighting was not the only peril – disease ran rampant in the canteen. Margaret was ill several times but luckily survived while many other women died from the Spanish flu.

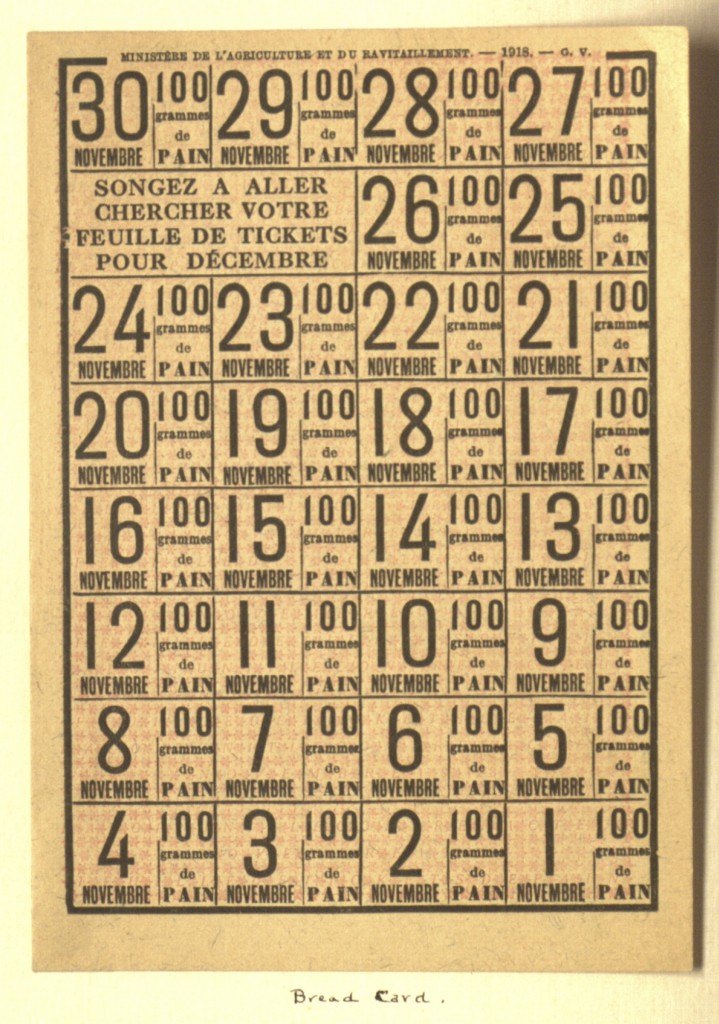

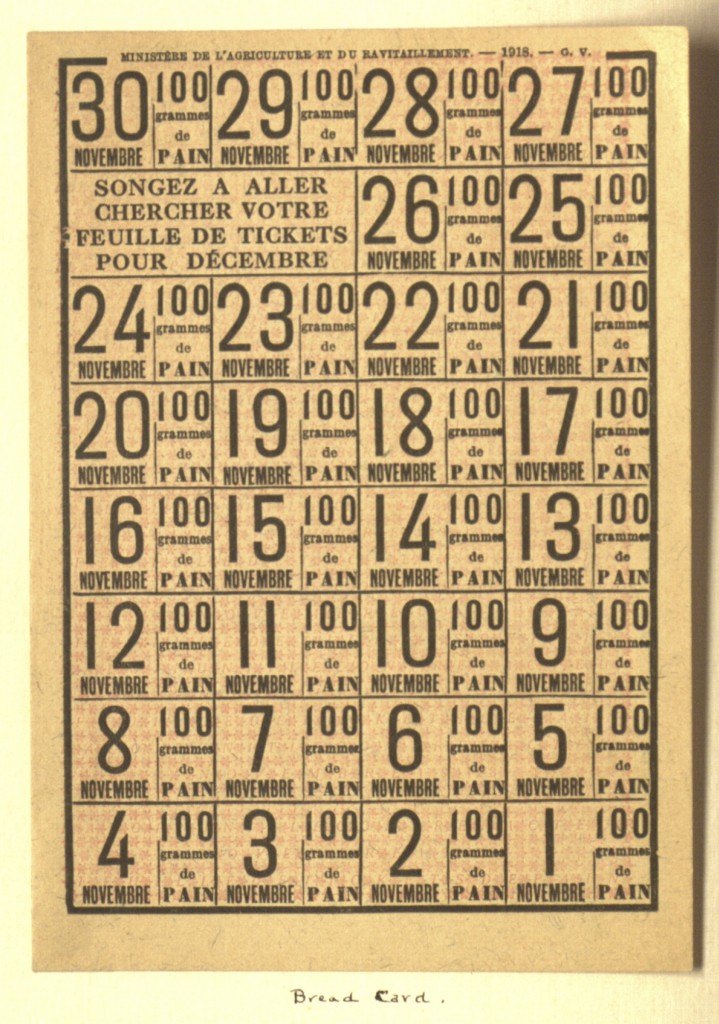

While reading her letters, I asked myself if I could do what she did and honestly, I’m still unsure. For a year, she lived a life completely different than anything she had ever known and for the first time, she encountered Algerians, “Anamites” (Vietnamese), Poles, “a real American Indian”, among others. There were food rations, she had little sleep or privacy, and saw countless dead and wounded soldiers. I cannot imagine how difficult it must have been to adjust to this environment. But, as Margaret points out, the four-year war made miserable conditions the norm and the end brought anything but peace: “Discontent is rampant in all branches of the service and among all nations. It’s a most deplorable ending to the four-years of agony. Not one definite thing accomplished, Allies loving each other less than ever” (178).

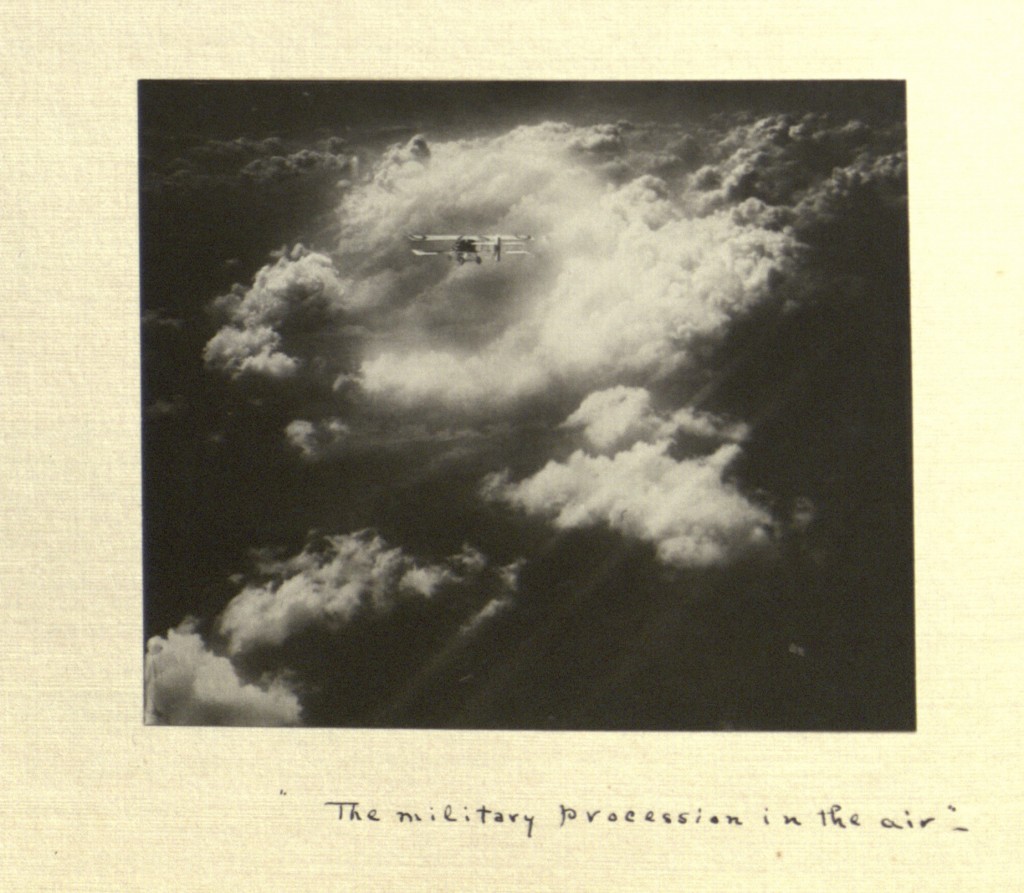

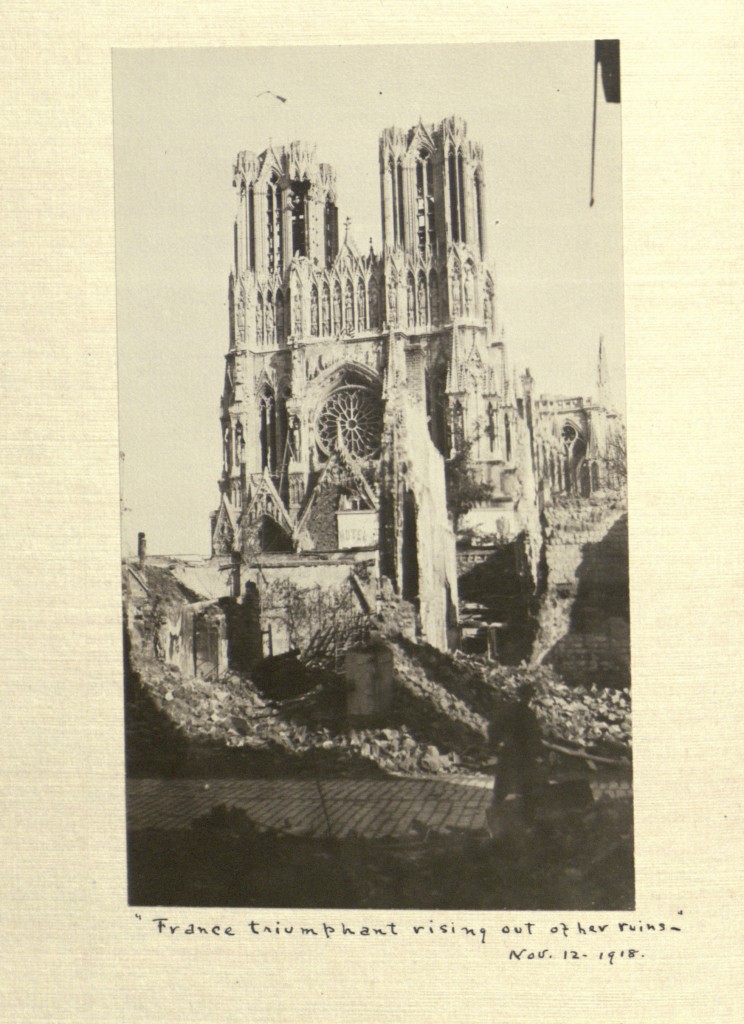

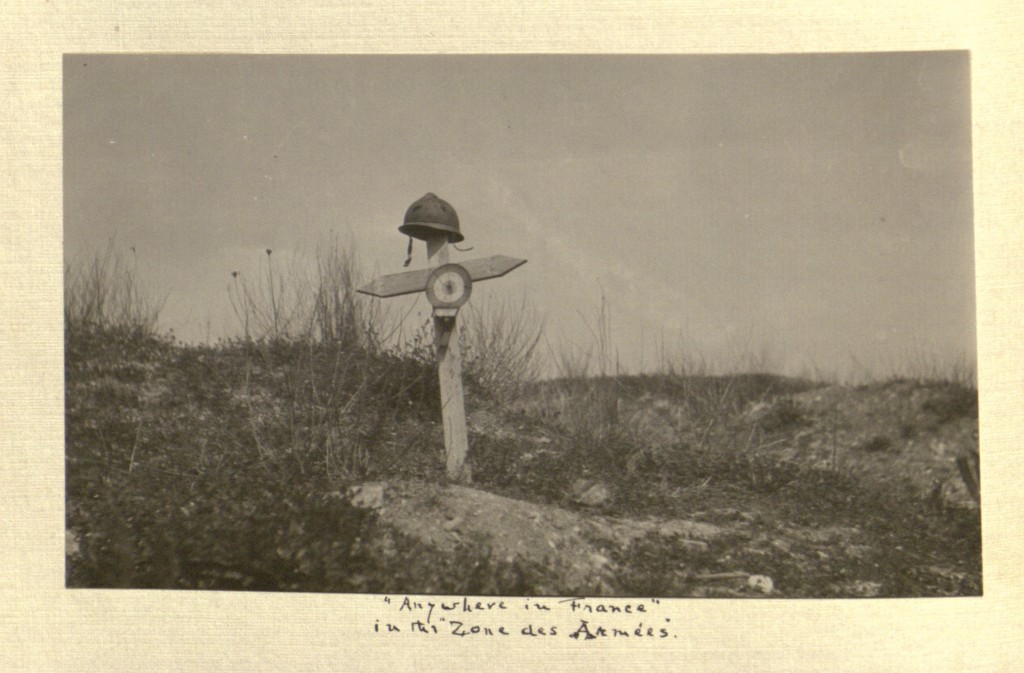

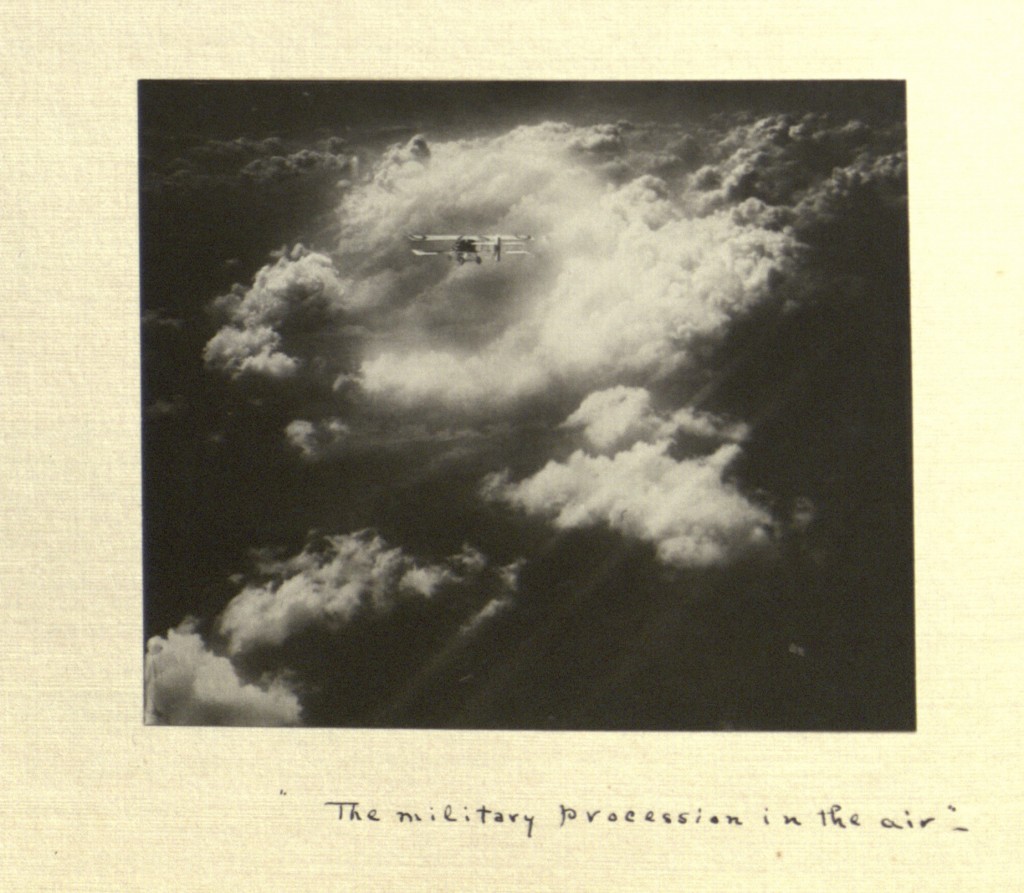

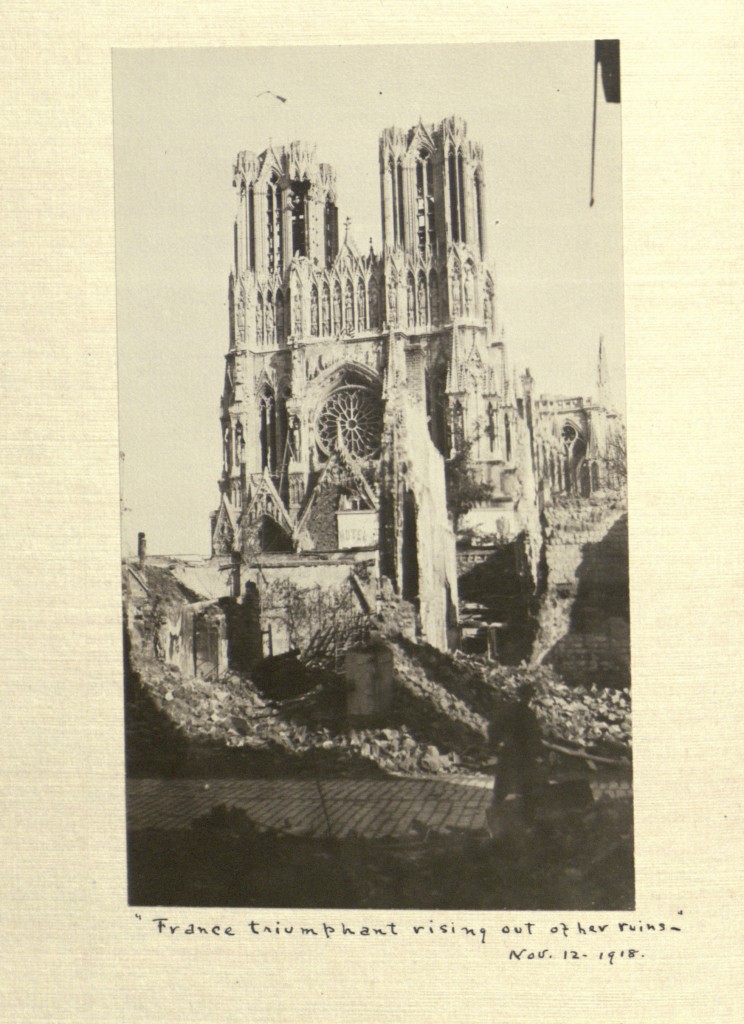

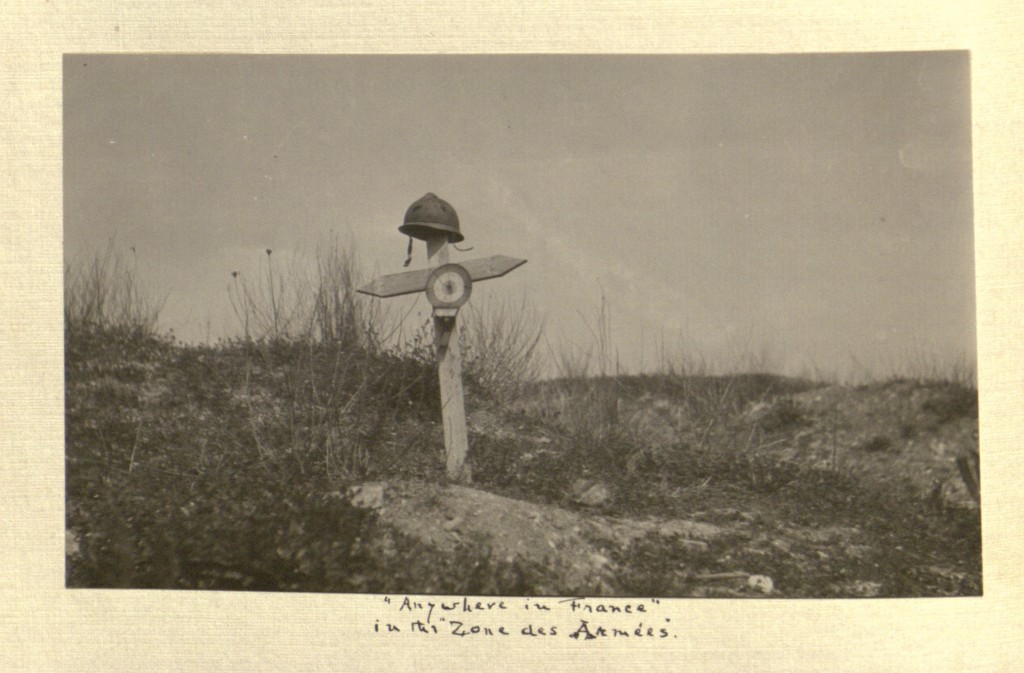

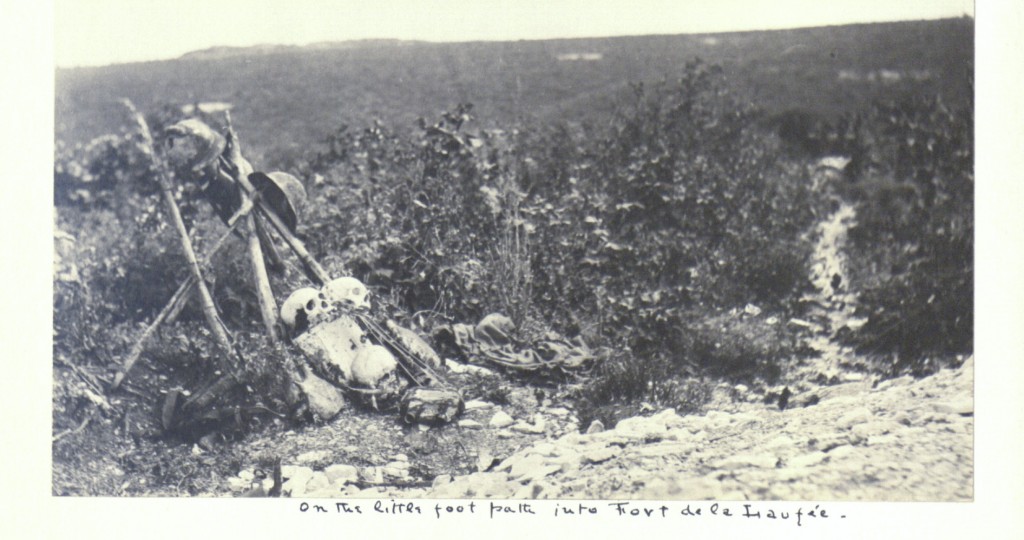

As an amateur photographer myself, I was particularly taken with Margaret’s pictures throughout her narrative. She snuck her camera past Paris customs, allowing her to capture hundreds of scenes from the Western front. Visually documenting the war was clearly very important to her: “One of the things most wearing to me is the desire to get out to take pictures, and the impossibility of doing it. I know I could get such wonderful things” (160). Keep in mind; she was using an ‘old-fashioned’ film camera. I can’t know for sure, but it is highly likely she used a Vest Pocket Kodak camera, which was introduced in 1912. As the name suggests, it was small enough to fit in a pocket, which might explain how she managed to smuggle her camera past customs. One roll of film, at maximum, could take sixteen pictures and she took many more than that. This means that Margaret would have had to find a pitch black area to change film rolls or else the negatives would be ruined. Speaking from experience, removing film is not the easiest thing to do and it definitely takes practice. Or, she could have had someone else do it for her. Regardless, it is interesting to really think about the physical process of photography in 1917 and the thought that was put into each picture she took.

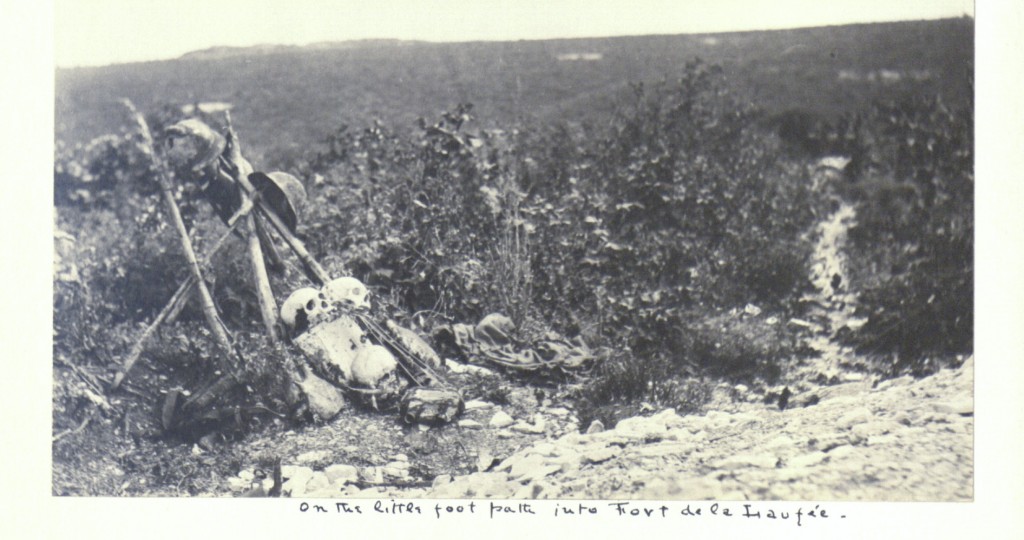

I learned a lot about Margaret by looking at her pictures; they show what and who she thought was worth photographing. Hall was both fascinated and horrified by the amount of destruction due to the fighting: “In the afternoon we walked to the little town of Courteau, all shelled up and as picturesque as the dickens” (129). The majority of her photographs are scenes of desolate land, abandoned weapons, destroyed buildings and graves. Many of her photos are artistically well composed and there are also candid shots of Allie solders and German prisoners. Margaret looked at the war from all angles and it is amazing to have such a dynamic collection of photographs all in one book.

I was quite struck by her response to corpses and demolished towns or buildings. She often described these scenes as “picturesque,” which I understand as there is allure in the grotesque. But, her description of the looting she did with other women from the canteen and the treatment of German bodies show a level of desensitization. “On our way down, found a dugout in which were ten or twelve Germans who had been gassed…It seemed only musty down there, not really disagreeable at all…Their hands were mummified, but you could almost see the muscles in their broad shoulders. Probably the gas, and being so far down away from the air, had preserved them. Don’t know how I ever could have gone into such a place. The only reason must be because they were our enemies and you don’t feel the same about them as you do about anything else in the world” (223). I think Margaret was surprised by her actions as well but accepted them rather than changed them. I thought that this looting expedition was particularly disturbing: “I am going to find a Boche prisoner now to fix up my souvenirs. Two women of the canteen are taking skulls as ‘souvenirs,’ and some of the nurses pull belts and boots off of dead Germans. Sometimes the feet come off in the boots, but that seems to be no objection!” (178). Not only was looting disrespectful to the dead, it was also extremely perilous: “People are killed and injured all the time for hunting souvenirs” because the abandoned trenches and battlefields were littered with hand grenades and other explosives. Plus, these women were traveling into foreign lands with people they met along the way. But, Hall maintained this mentality: “But why be here in the midst of it and not see it, even if it kills you in the end!” (135). Or as we would say today, #YOLO.

Hall describes a conversation with a German prisoner that is an eerily accurate prediction for the future: “The Germans say, ‘Just wait six years.’ I think they have no intention of remaining a conquered nation longer than that” (153). He [German boy] is convinced that he will go home in a month or two at most, or else the war will begin again. Germany will have her prisoners back, he says. He’s a nice, industrious boy, but German, and they can never be changed; they will always wish to push their Kultur onto others. He told us their government was the best, and we’d all have to come to it sooner or later. I really felt quite hopeless after I’d talked to him” (158). This anecdote sent chills down my spine because we now know this solder’s declarations soon became a reality. Seven years after the war ended, Adolf Hitler published Mein Kampf and then became Chancellor of Germany in 1933. The rest, as they say, is history.

Elizabeth Reilly, Class of 2014

Elizabeth Reilly, Class of 2014

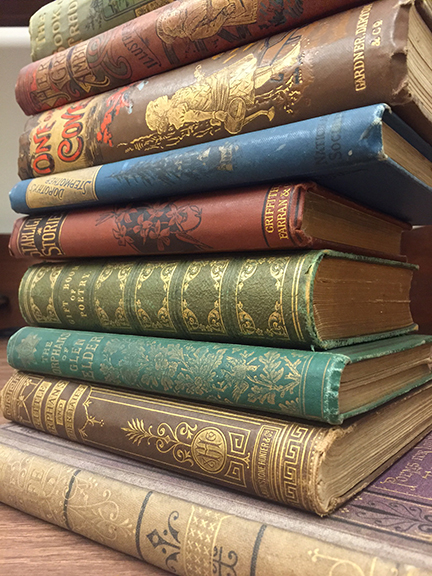

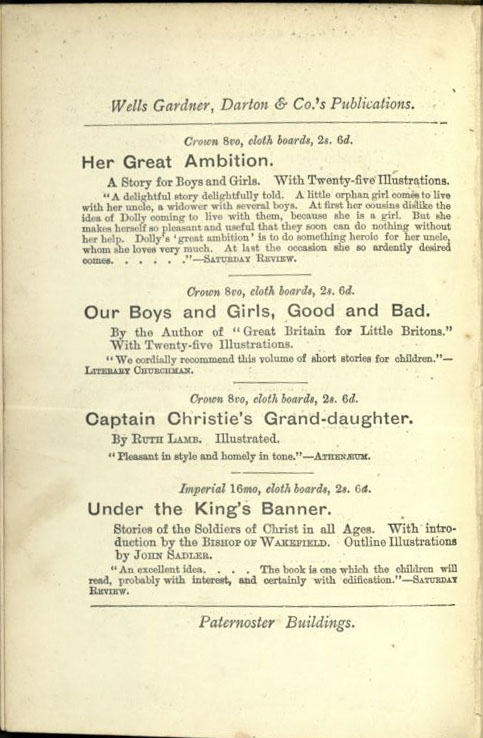

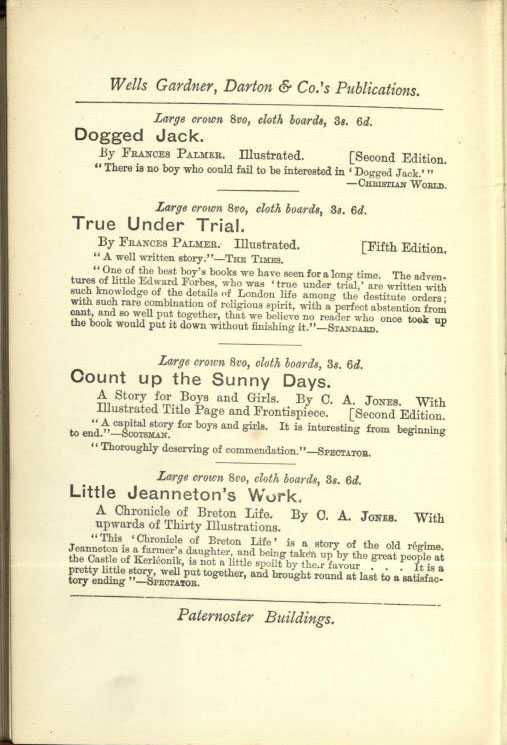

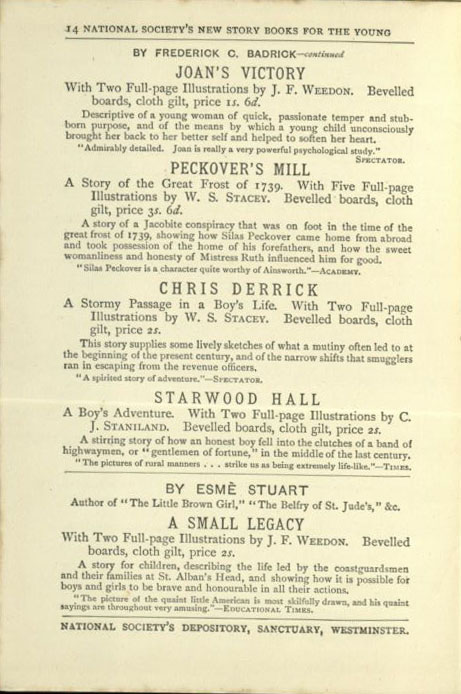

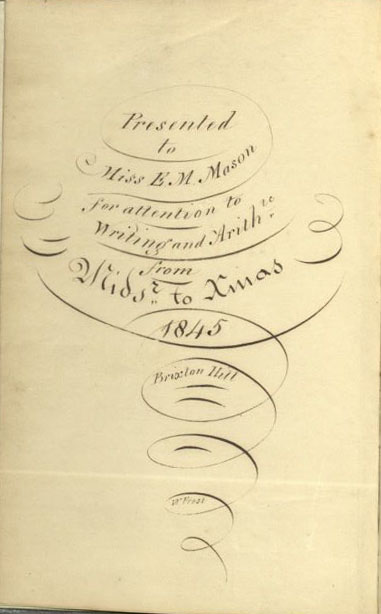

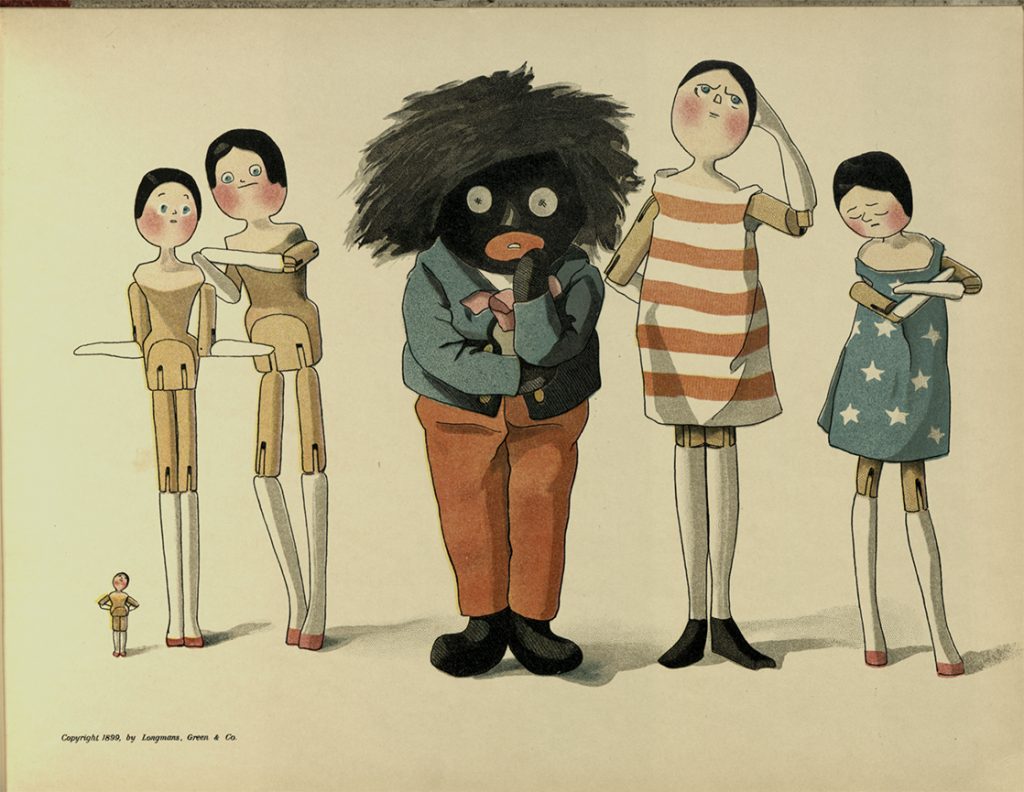

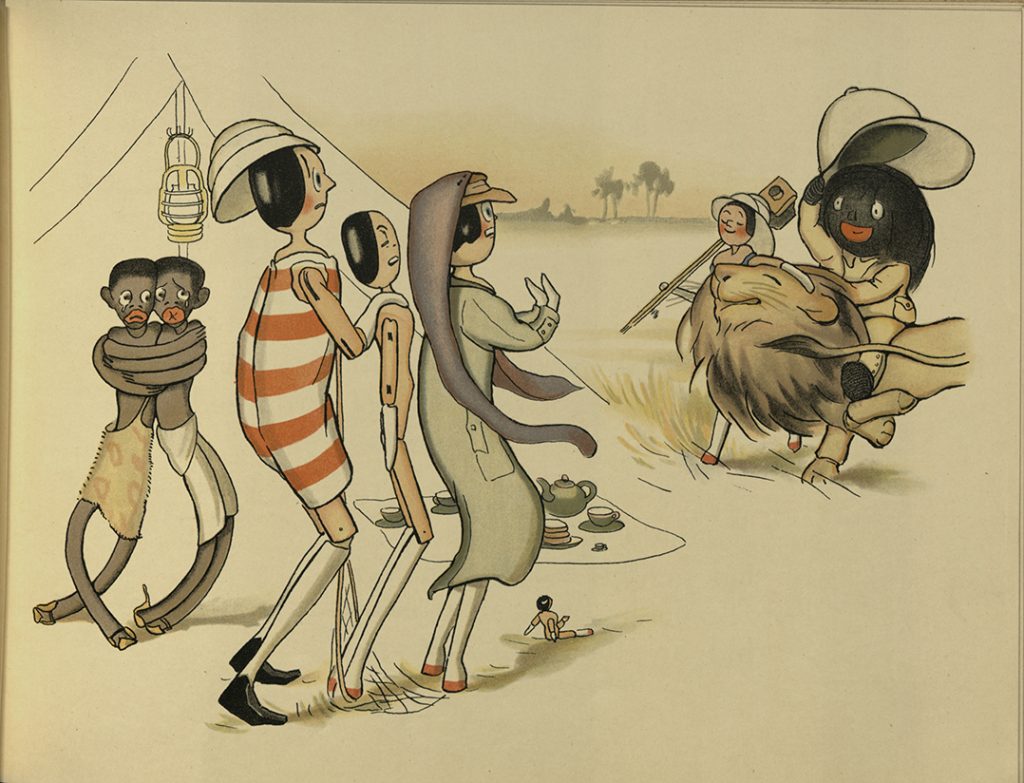

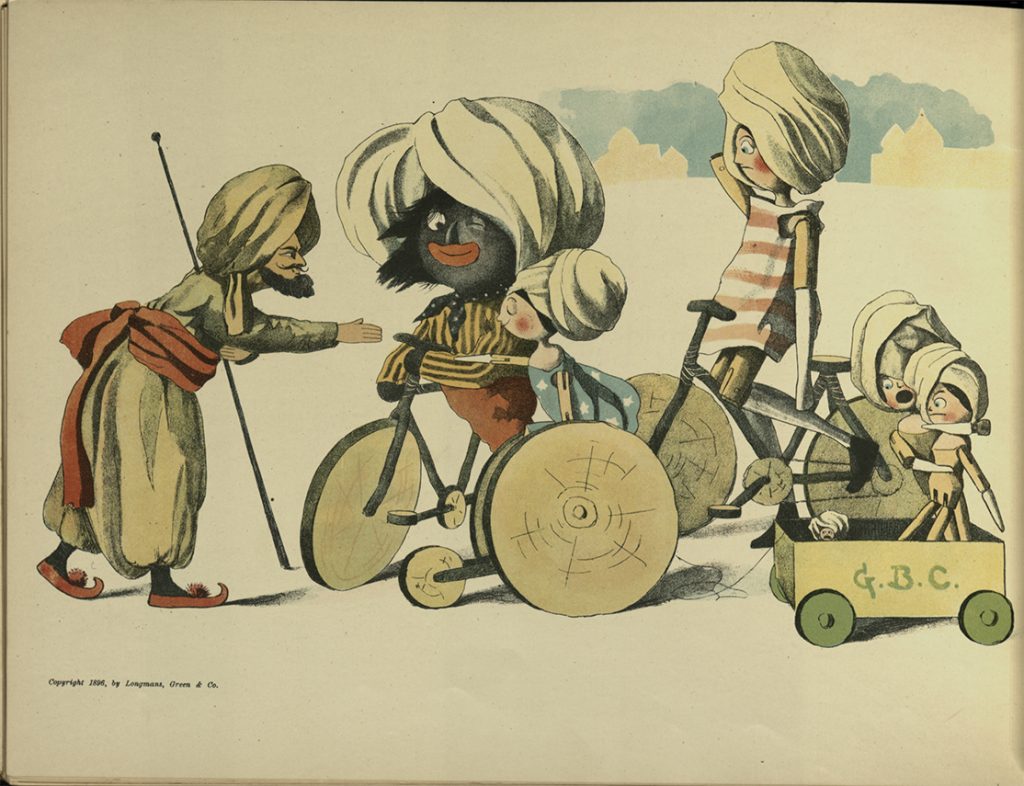

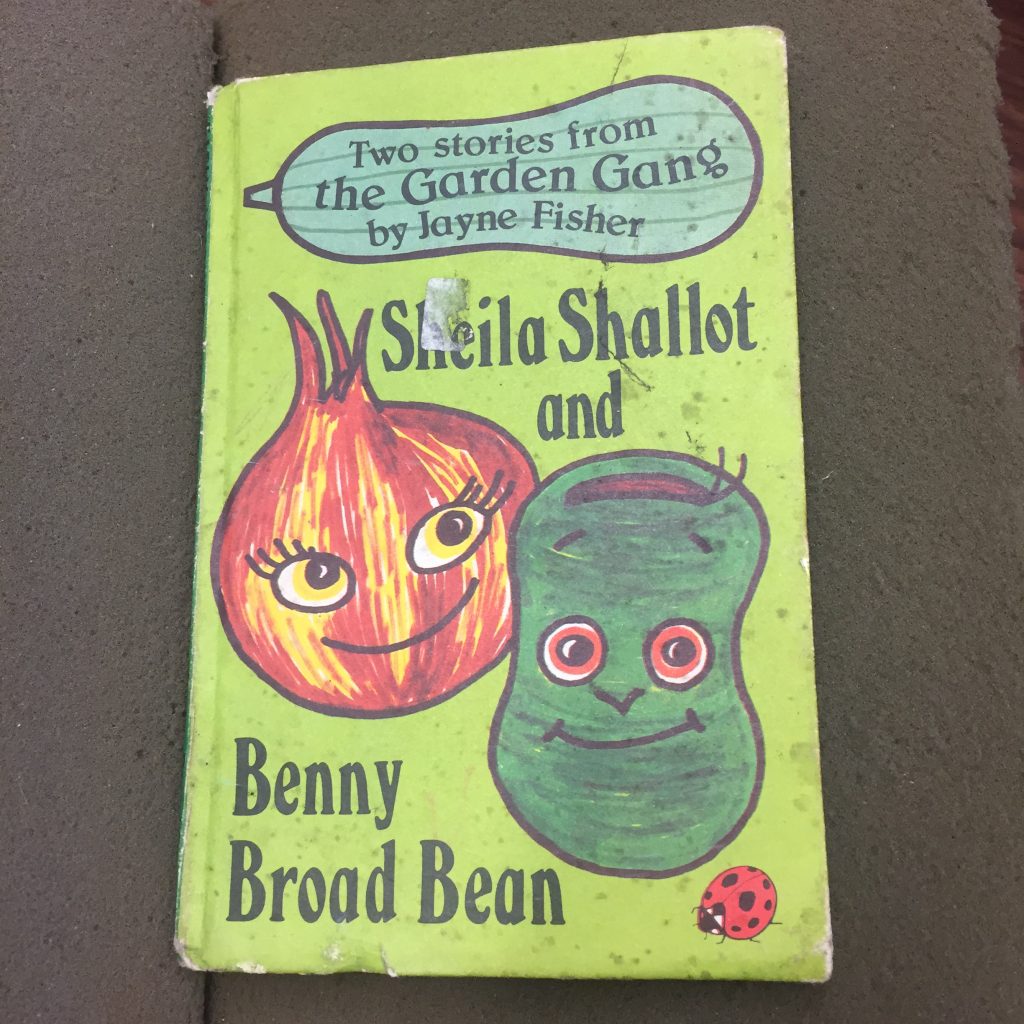

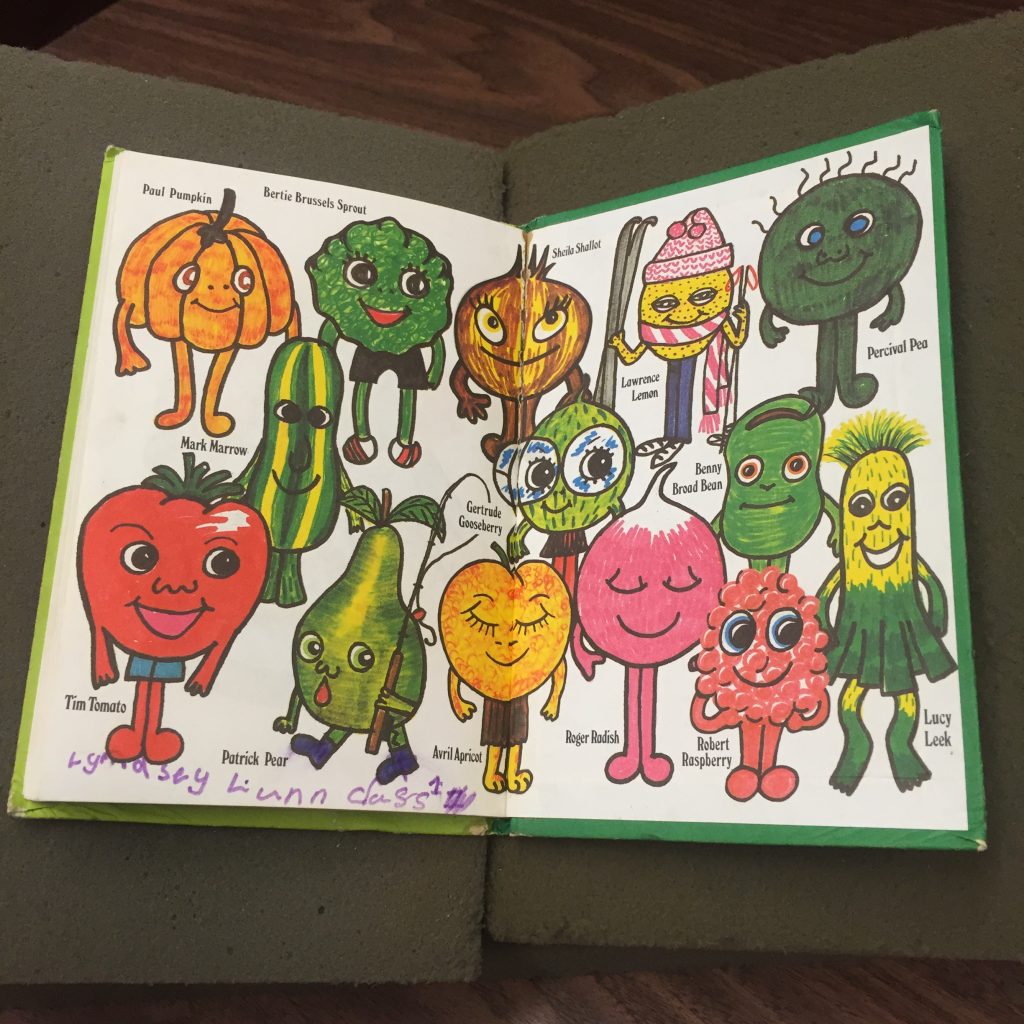

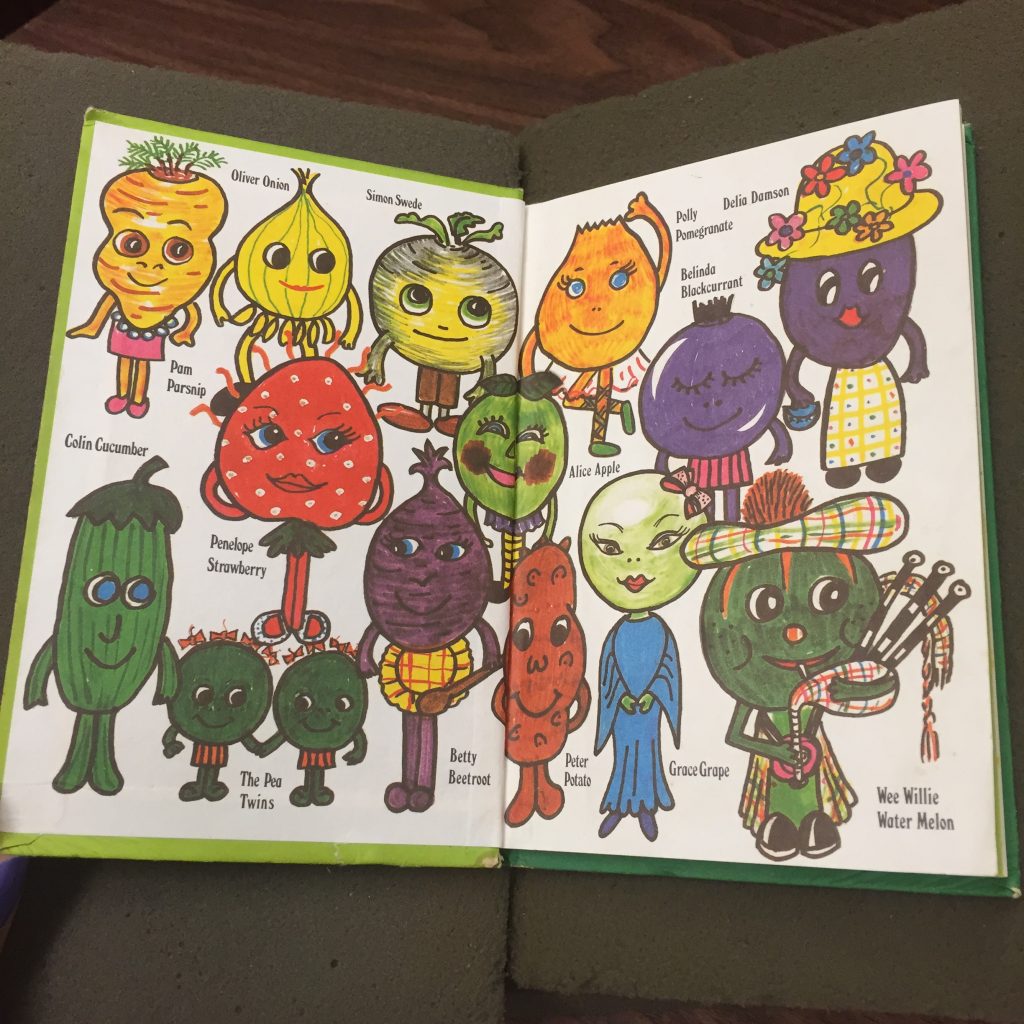

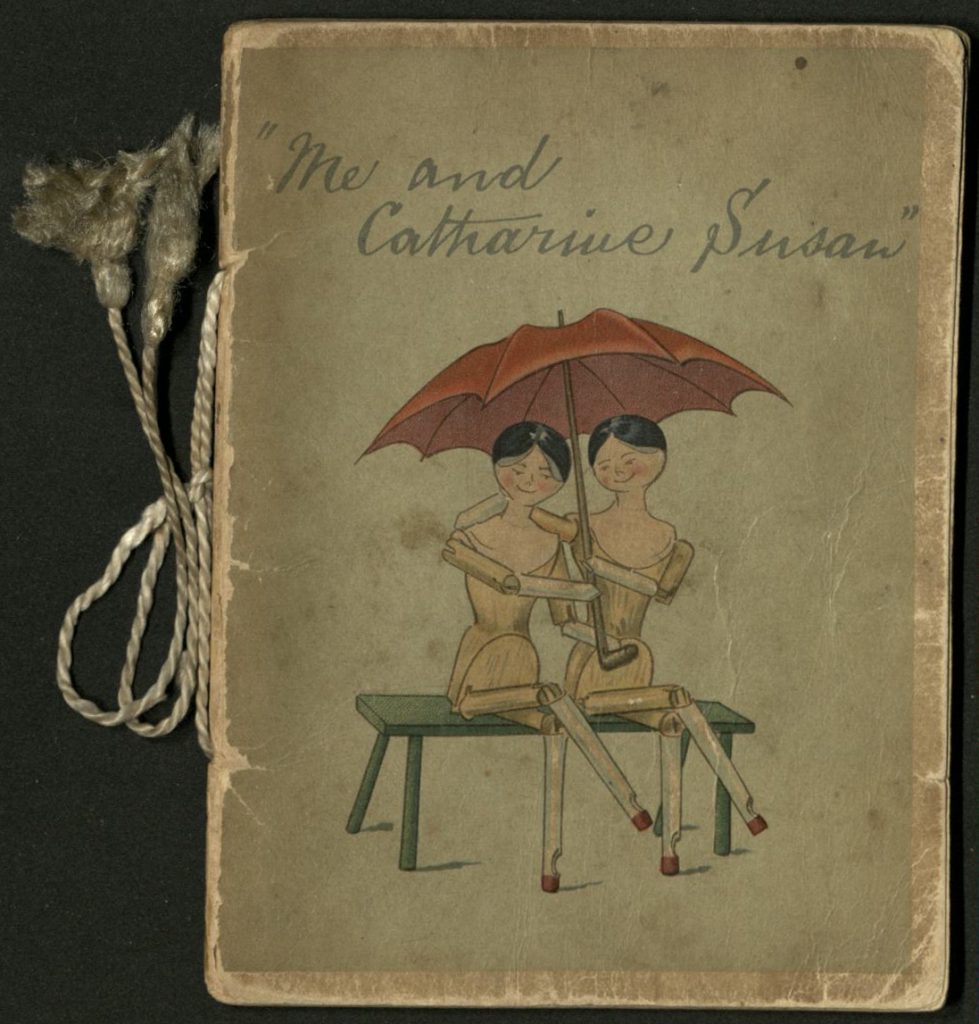

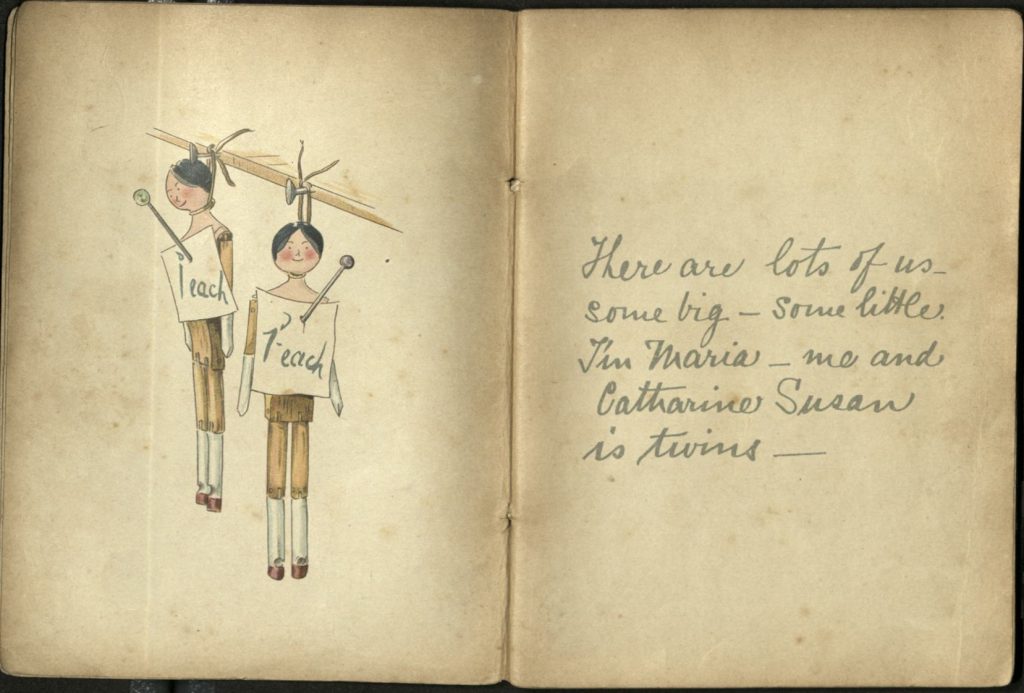

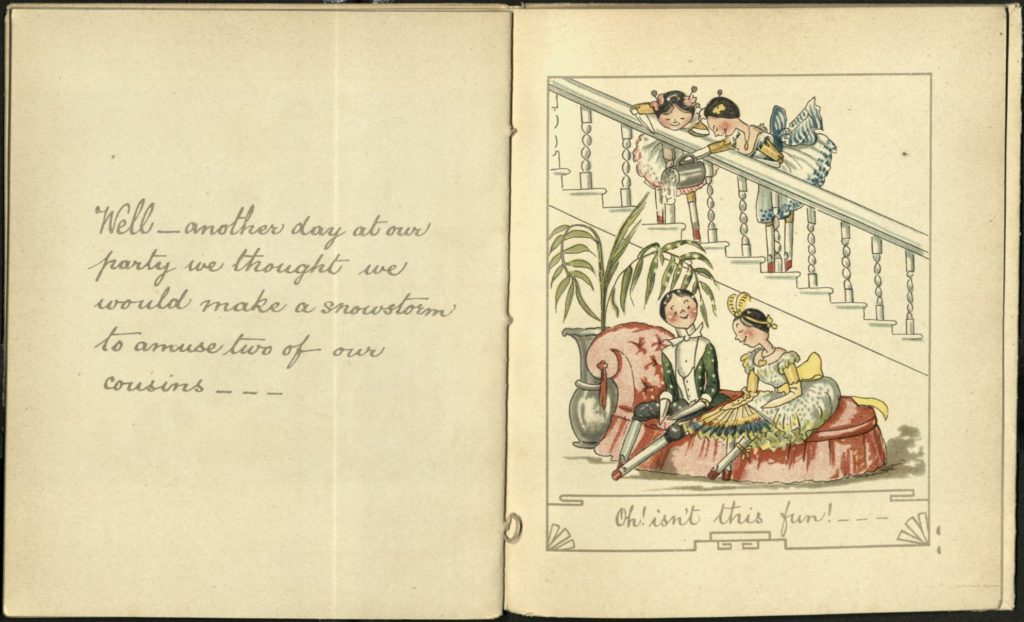

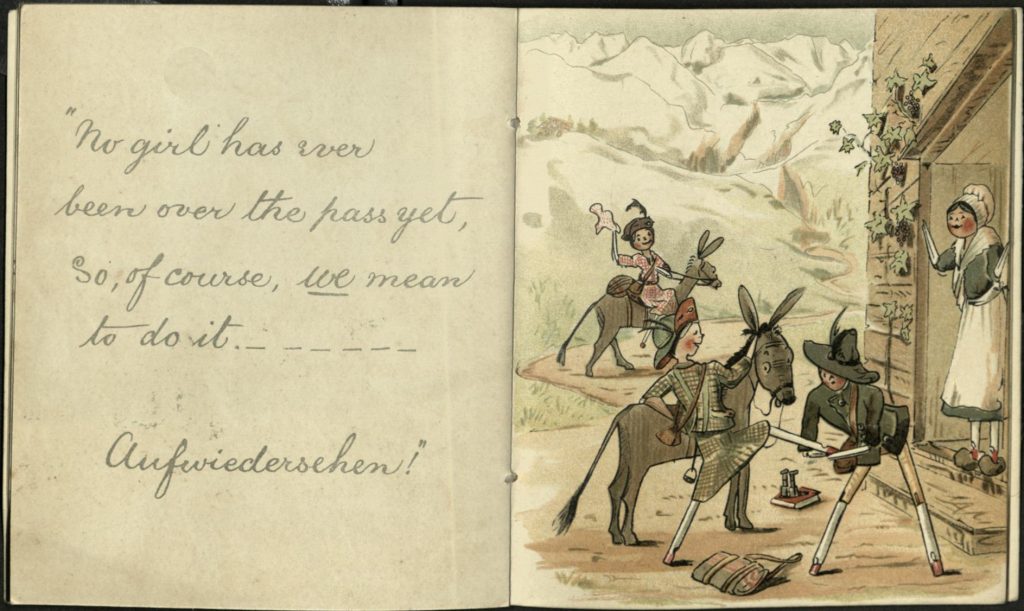

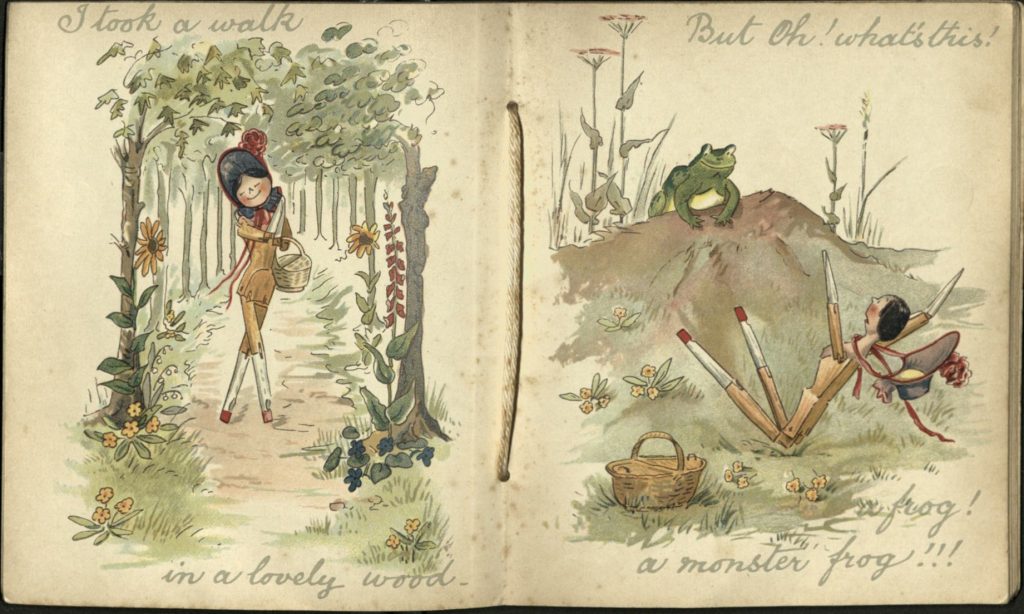

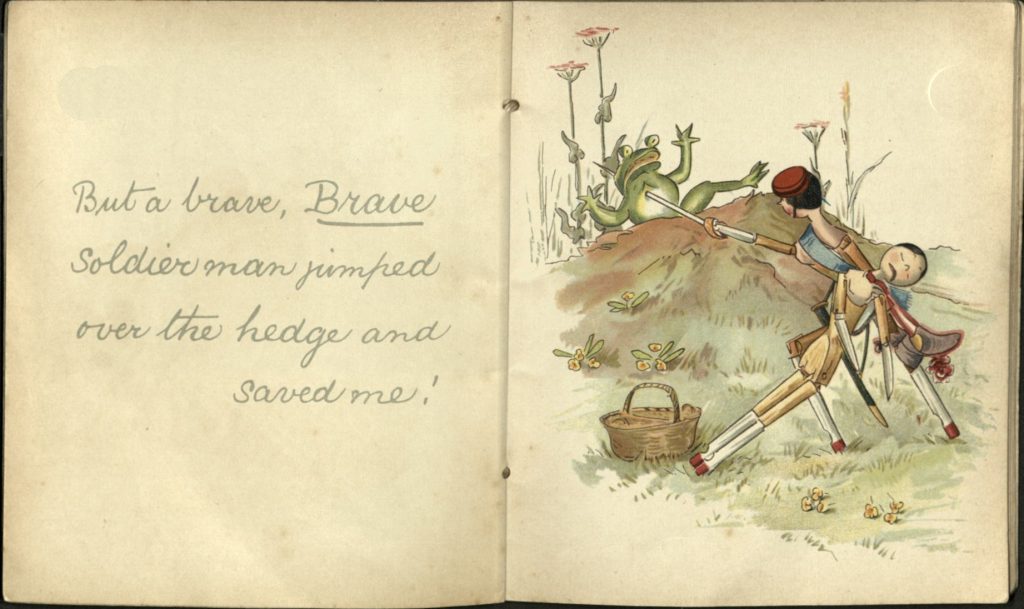

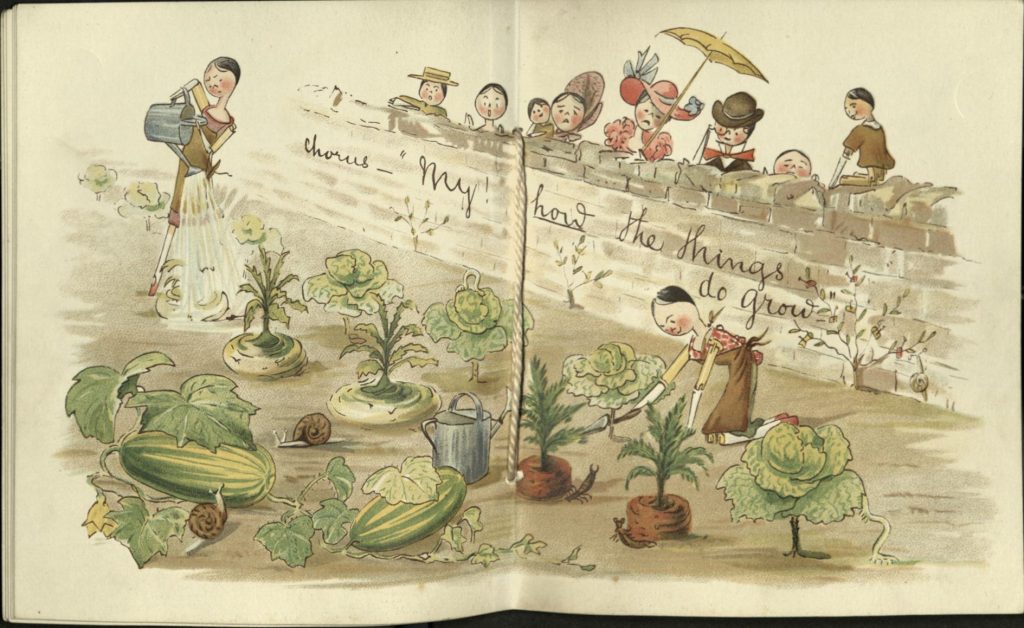

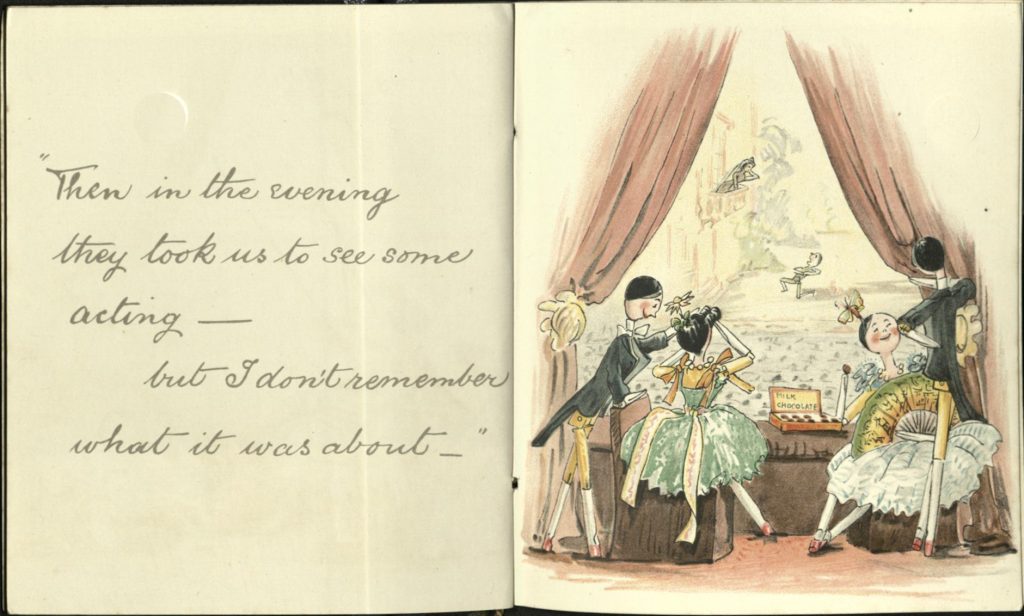

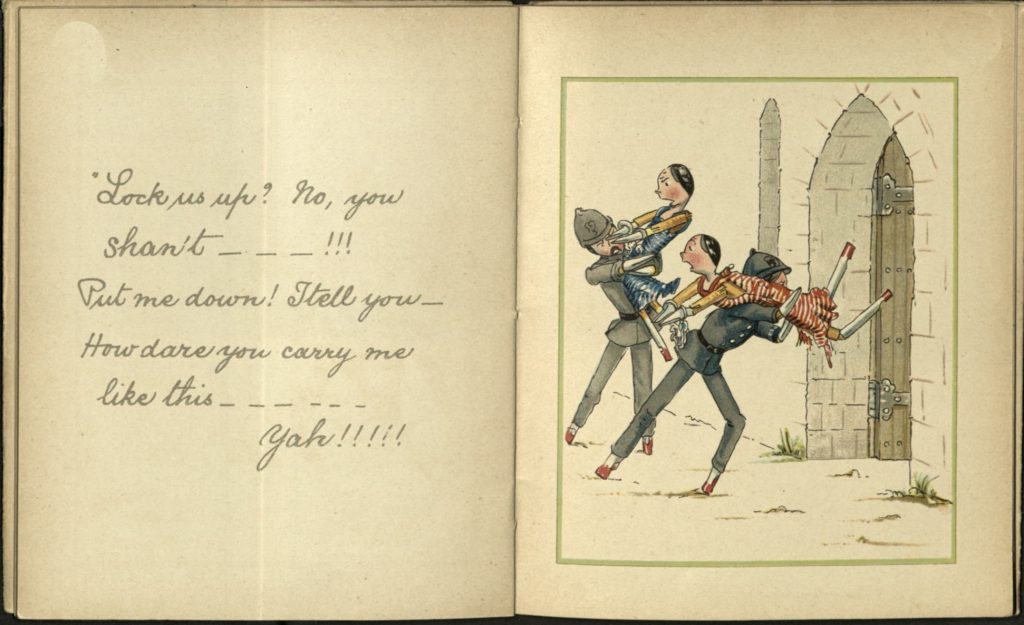

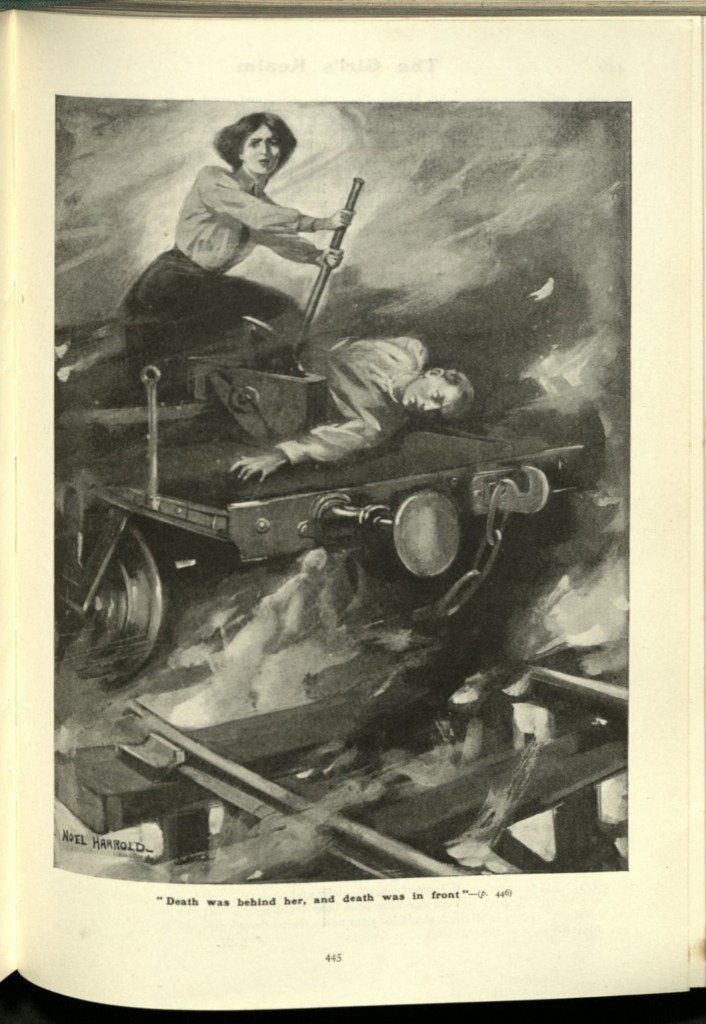

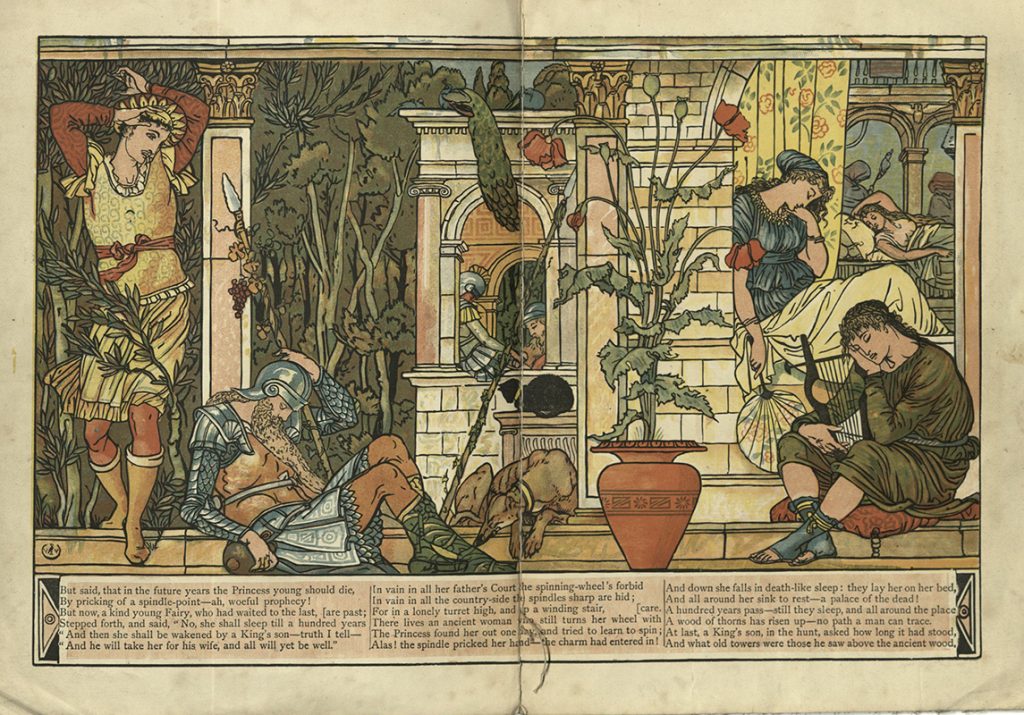

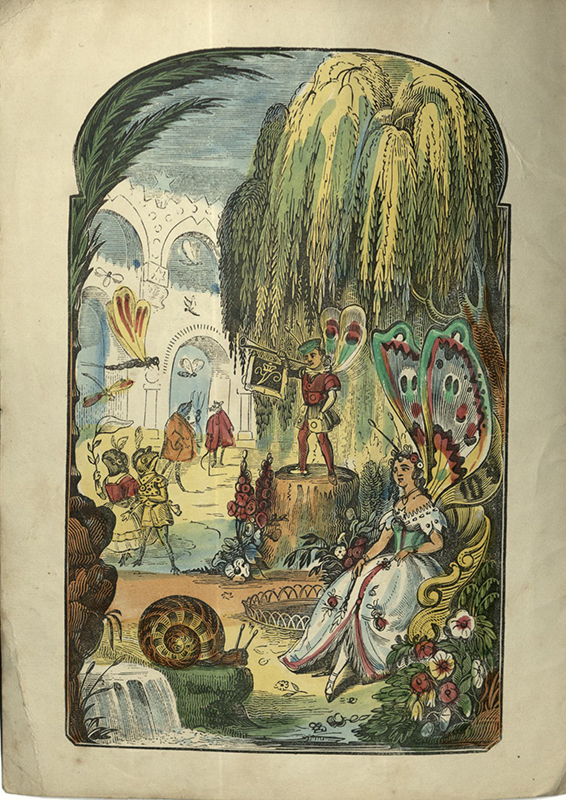

The collection has hundreds of volumes of fairy tales and folk tales. We are showing a spectacular Sleeping Beauty (1876) illustrated by Walter Crane, an Ainu story (Ho-Limlim: A Rabbit Tale from Japan, 1990) illustrated by the modern woodcut artist Keizaburō Tejima, and an 1871 collection of fairy tales illustrated by Gustave Doré.

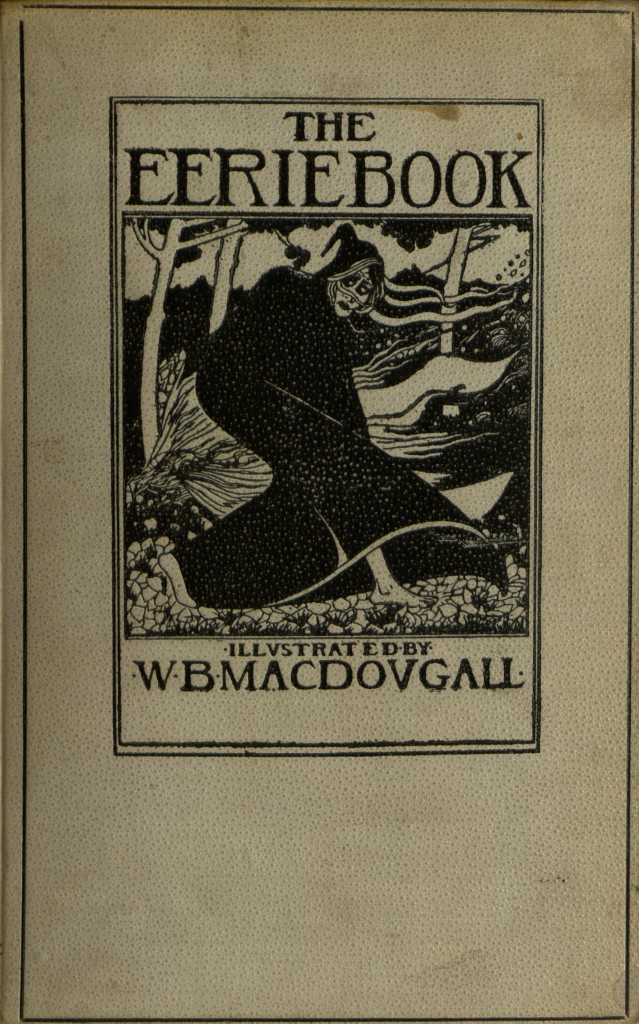

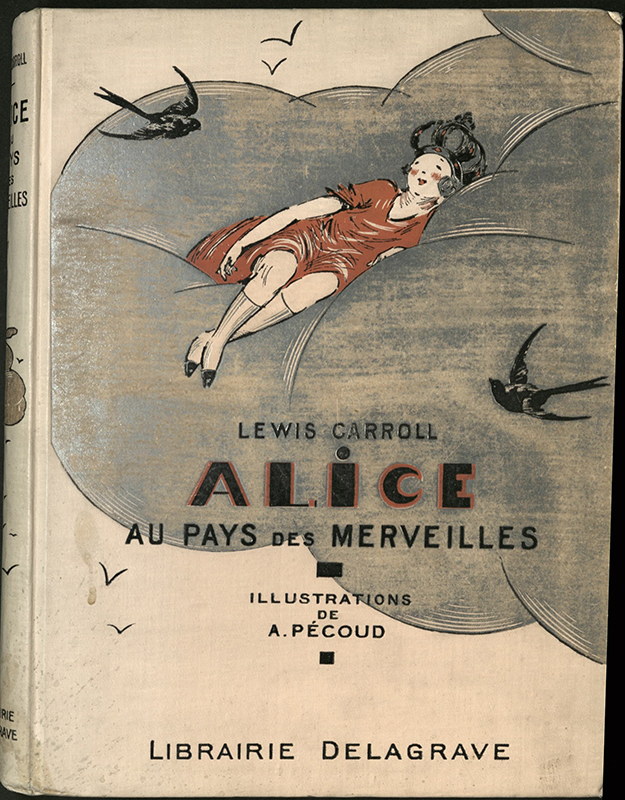

The collection has hundreds of volumes of fairy tales and folk tales. We are showing a spectacular Sleeping Beauty (1876) illustrated by Walter Crane, an Ainu story (Ho-Limlim: A Rabbit Tale from Japan, 1990) illustrated by the modern woodcut artist Keizaburō Tejima, and an 1871 collection of fairy tales illustrated by Gustave Doré. Fantasy literature is very well represented in the collection from its beginnings in the nineteenth century right through The Hobbit, Harry Potter, and Philip Pullman’s work. The exhibition includes first editions of Mary Poppins (1934) and The Amber Spyglass (2000), and a beautifully illustrated French Alice in Wonderland from 1935.

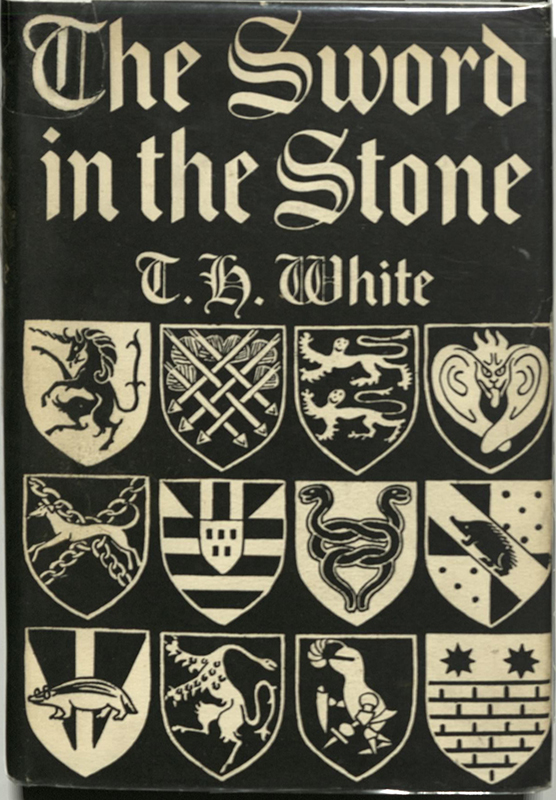

Fantasy literature is very well represented in the collection from its beginnings in the nineteenth century right through The Hobbit, Harry Potter, and Philip Pullman’s work. The exhibition includes first editions of Mary Poppins (1934) and The Amber Spyglass (2000), and a beautifully illustrated French Alice in Wonderland from 1935. Other young adult novels featured are The Sword in the Stone, by T.H. White,

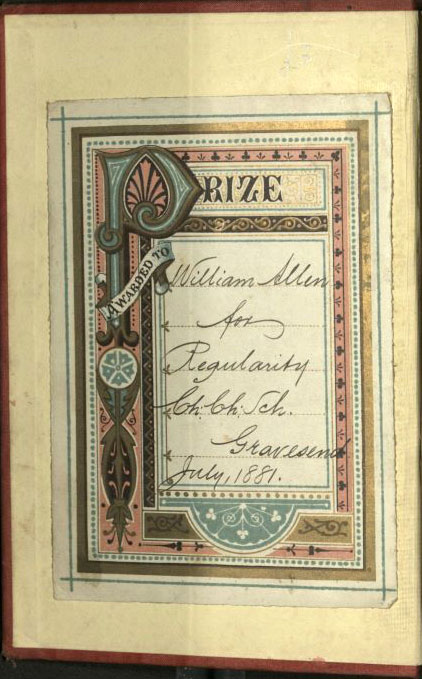

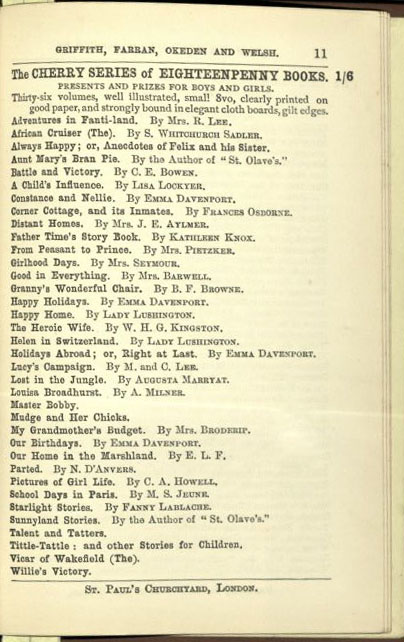

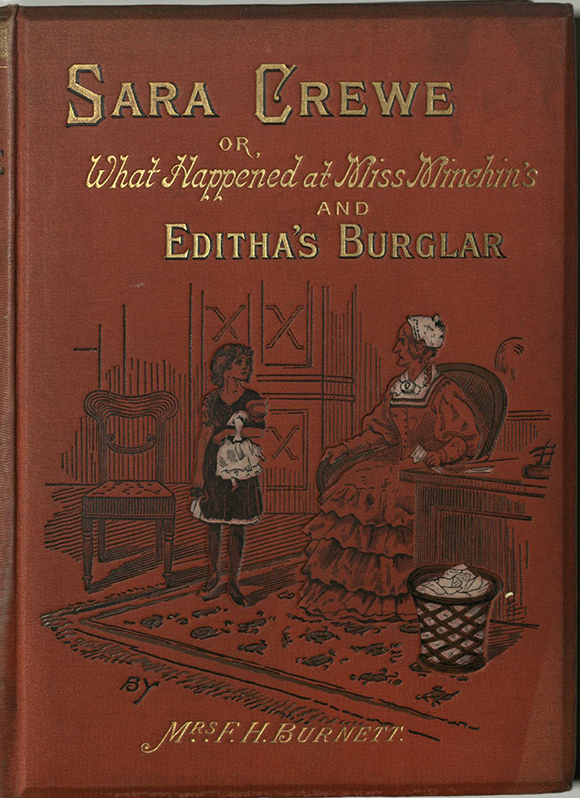

Other young adult novels featured are The Sword in the Stone, by T.H. White, and Tennis Shoes, by Noel Streatfeild, (both 1938); Frances Hodgson Burnett’s first version of A Little Princess (1888);

and Tennis Shoes, by Noel Streatfeild, (both 1938); Frances Hodgson Burnett’s first version of A Little Princess (1888);  Rosemary’s Sutcliff’s The Armourer’s House (1951), representing the important genre of historical novels; and one of the more than eighty novels written by Mrs Molesworth, a successful (although now little known) nineteenth-century author, The Trio in the Square (1898).

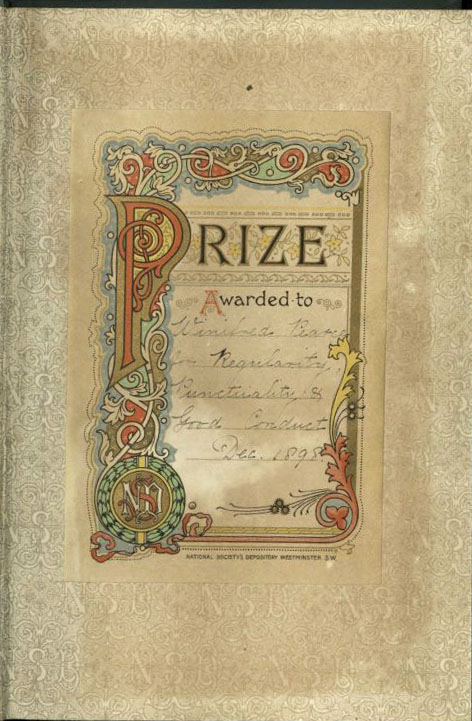

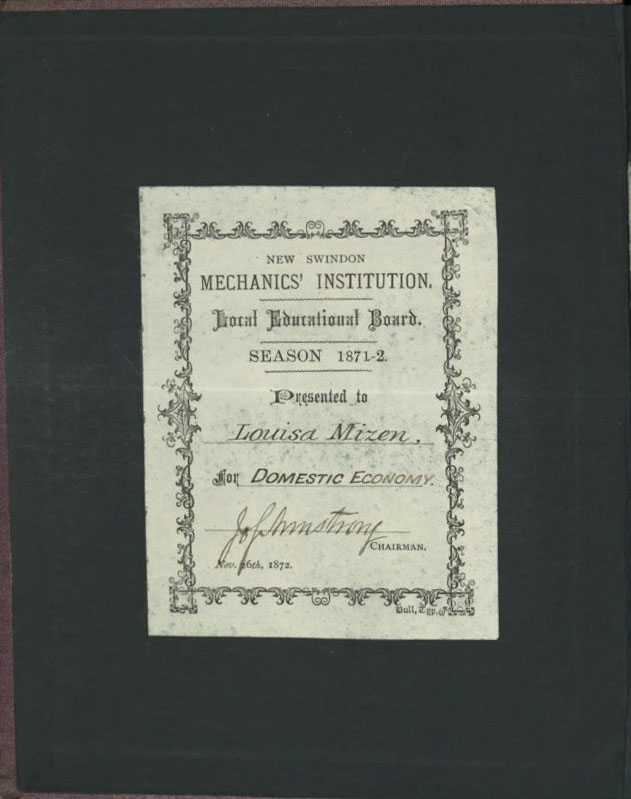

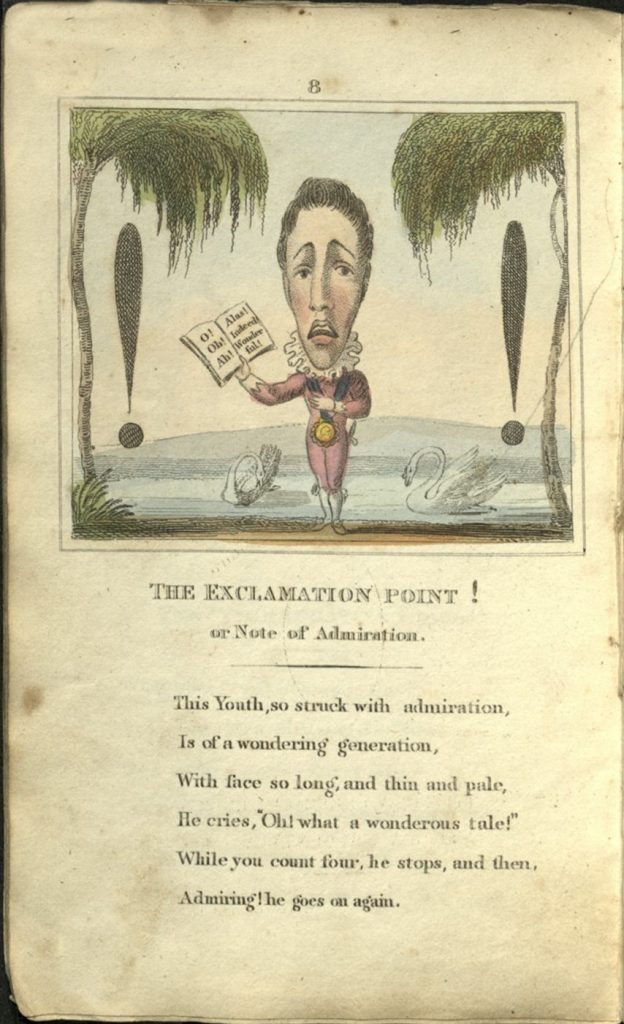

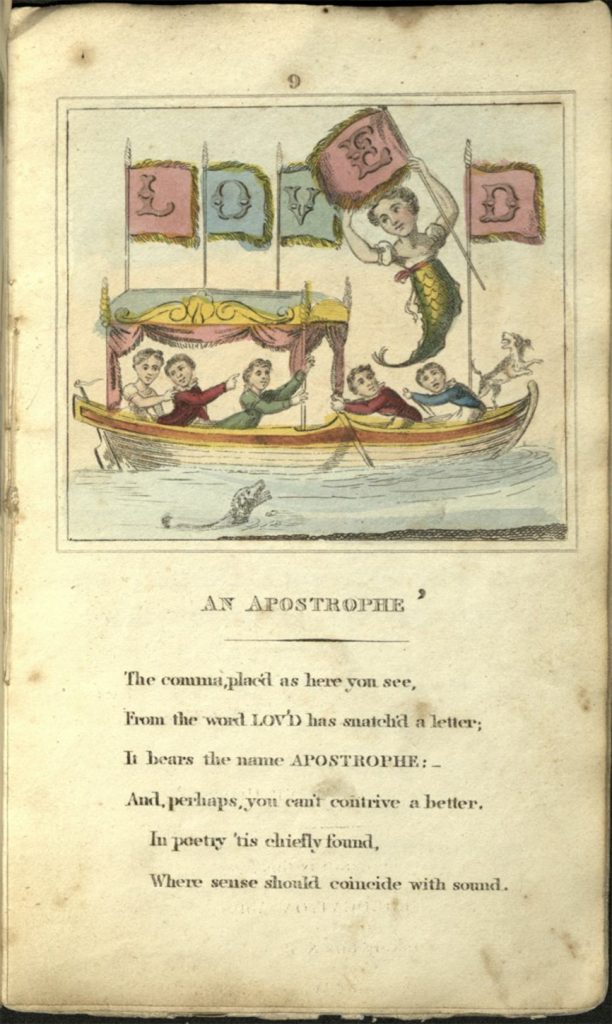

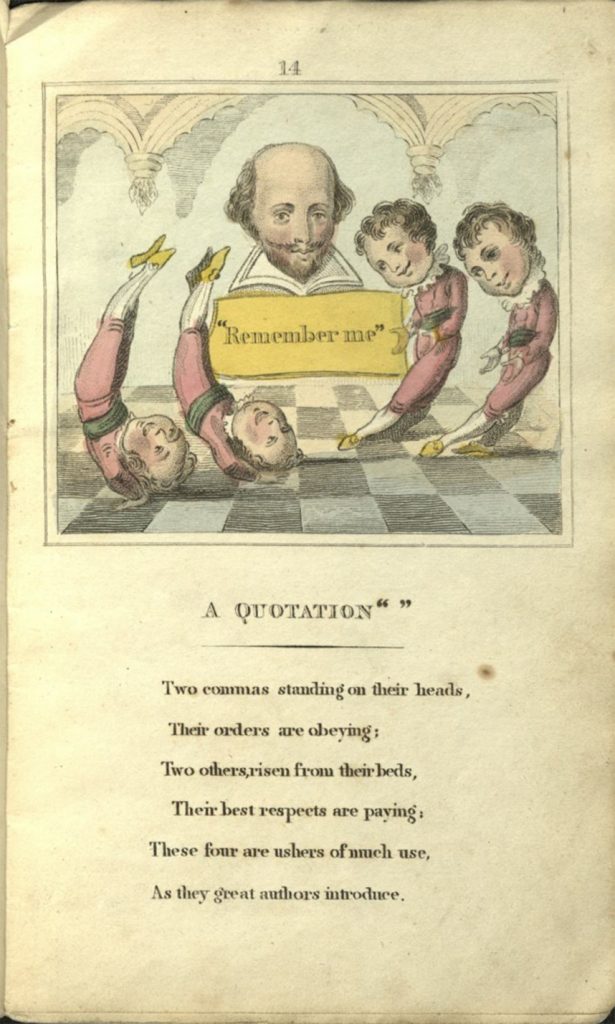

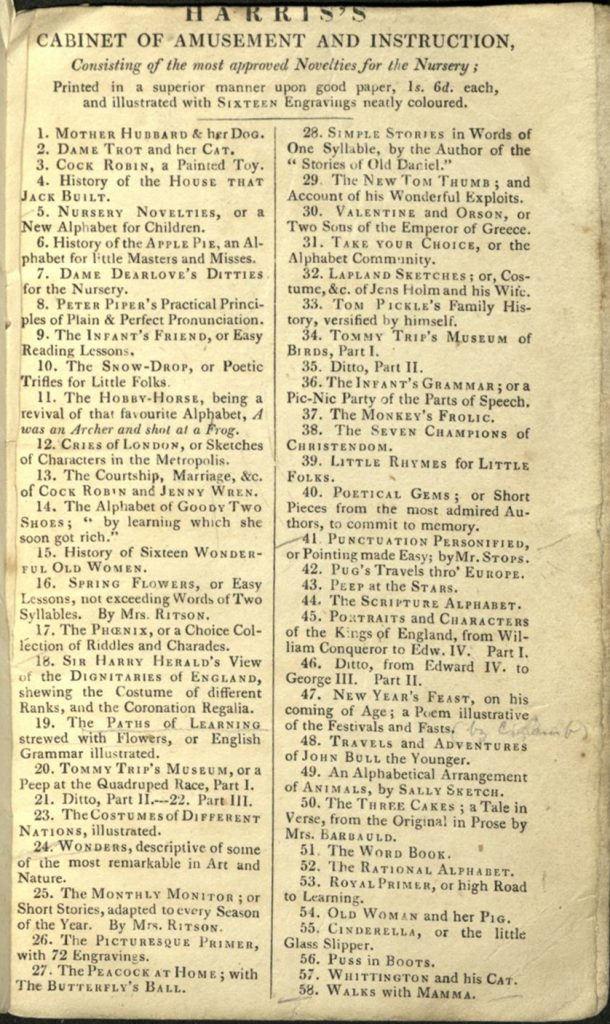

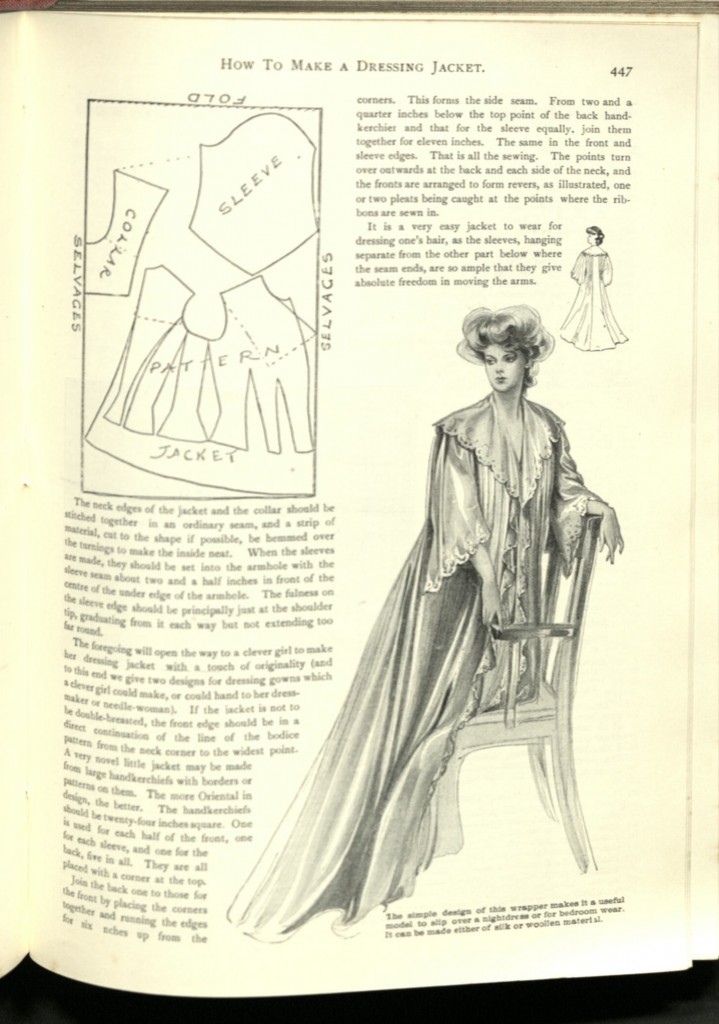

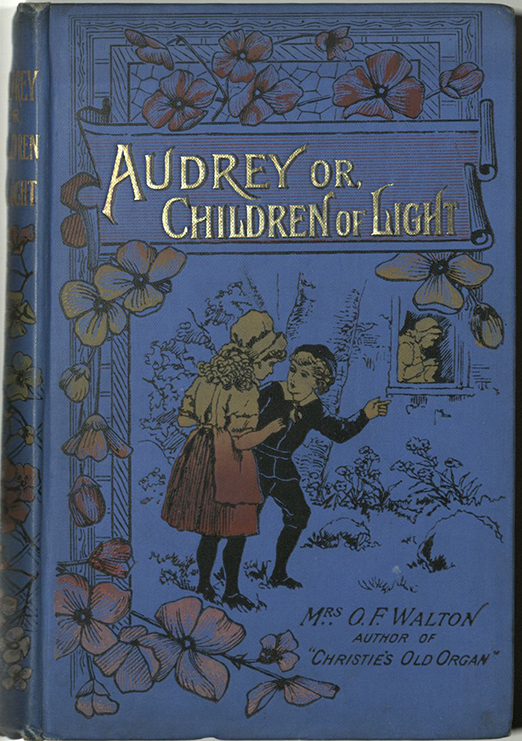

Rosemary’s Sutcliff’s The Armourer’s House (1951), representing the important genre of historical novels; and one of the more than eighty novels written by Mrs Molesworth, a successful (although now little known) nineteenth-century author, The Trio in the Square (1898). an ABC; an 1820 pamphlet on learning to read music; and the 1876 The Young Lady’s Book: A Manual of Amusements, Exercises, Studies, and Pursuits, with chapters on everything from cooking, sewing, and drawing to heraldry, stamp collecting, and archery. Attempts to make children better behaved are represented by Amy Catherine Walton’s religious novel Audrey, or, Children of Light (1897)

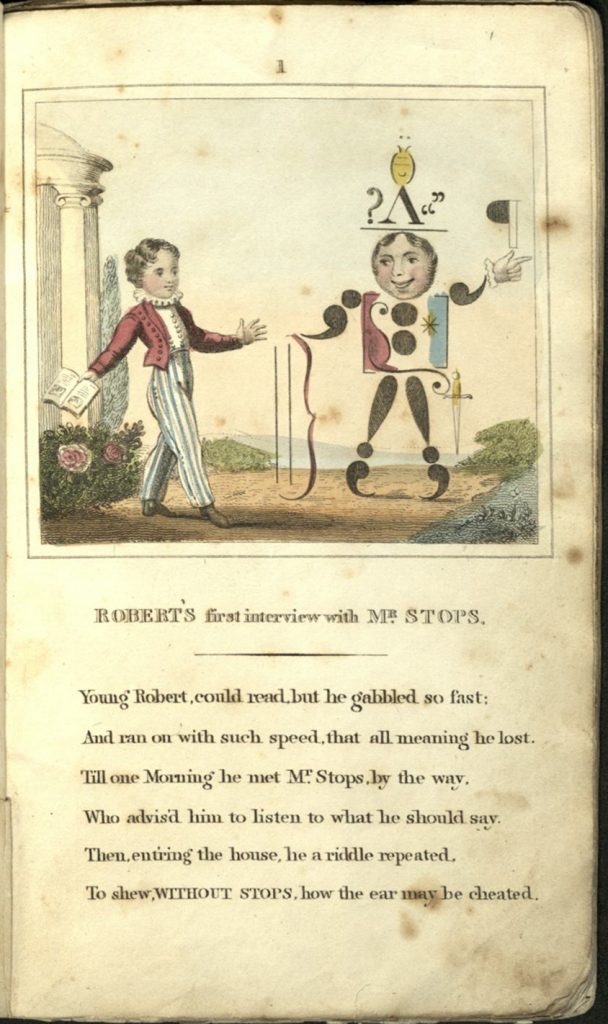

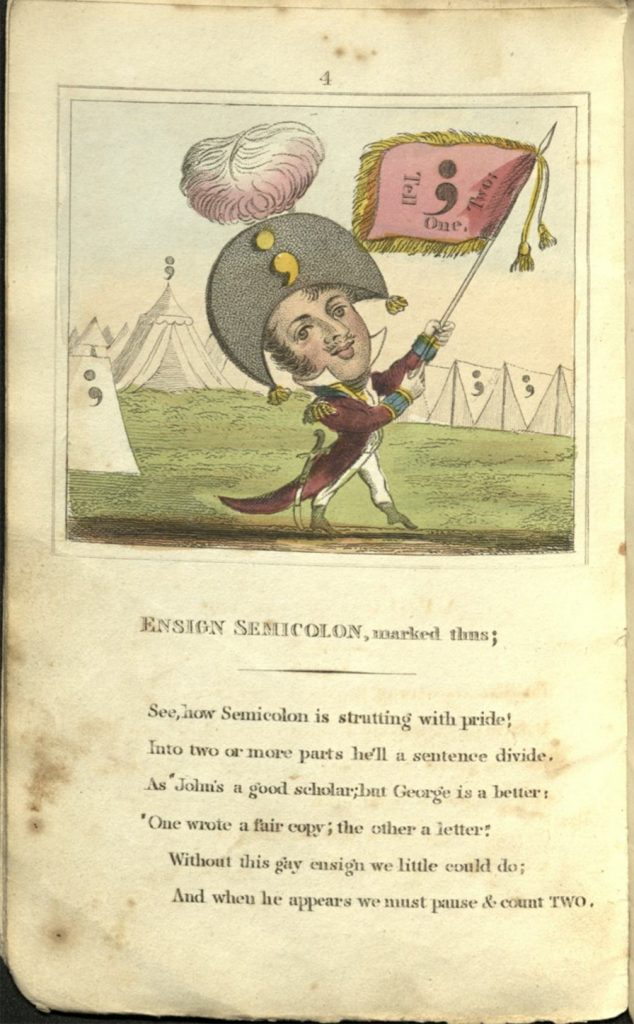

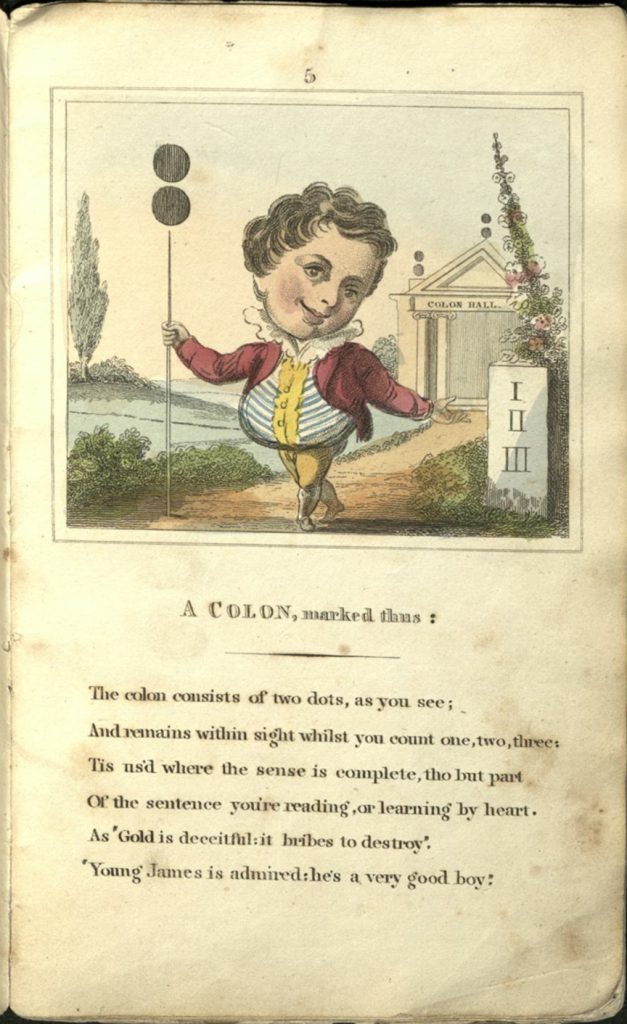

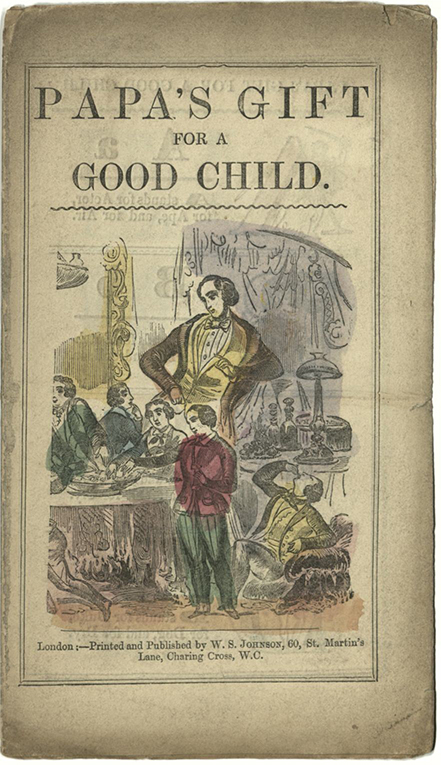

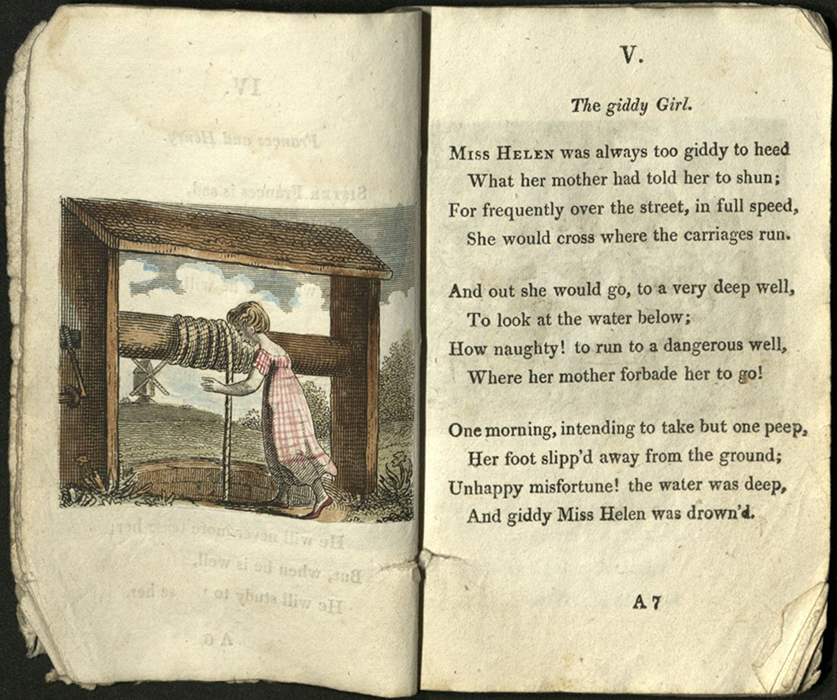

an ABC; an 1820 pamphlet on learning to read music; and the 1876 The Young Lady’s Book: A Manual of Amusements, Exercises, Studies, and Pursuits, with chapters on everything from cooking, sewing, and drawing to heraldry, stamp collecting, and archery. Attempts to make children better behaved are represented by Amy Catherine Walton’s religious novel Audrey, or, Children of Light (1897)  and by The Daisy, or, Cautionary Stories in Verse: Adapted to the Ideas of Children from Four to Eight Years Old (1807).

and by The Daisy, or, Cautionary Stories in Verse: Adapted to the Ideas of Children from Four to Eight Years Old (1807).  Six Stories for the Nursery: In Words of One and Two Syllables crosses the mind/morals divide by trying to teach reading and manners simultaneously.

Six Stories for the Nursery: In Words of One and Two Syllables crosses the mind/morals divide by trying to teach reading and manners simultaneously. We cannot offer you an elegant supper, but we do hope you will drop by to look at the books – and that you will be increasingly delighted.

We cannot offer you an elegant supper, but we do hope you will drop by to look at the books – and that you will be increasingly delighted.