For the past several months, I have been privileged enough to work with the Bryn Mawr oral histories as part of my work for The Albert M. Greenfield Digital Center for the History of Women’s Education. The oral histories are comprised of hundreds of old cassette tapes, containing interviews, speeches, and lectures with Bryn Mawr alumnae, professors, staff, and other members of the college community. Although they are not available to the public at the moment, my job includes listening to the tapes and digitizing them. The long-term goal is that they will one day be a part of a public digital archive. In the meantime, I want to share some of the fun, surprising, and enlightening facts I have learned about Bryn Mawr through my work.

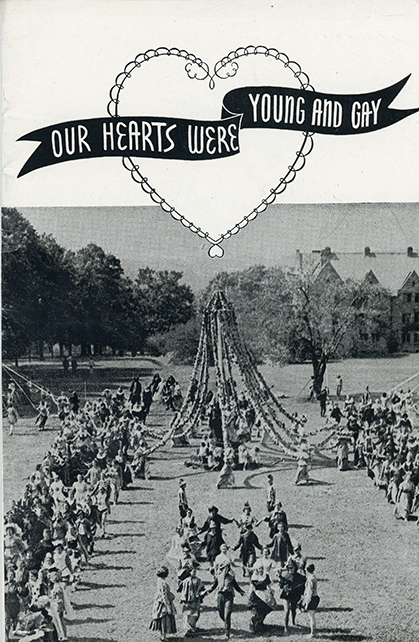

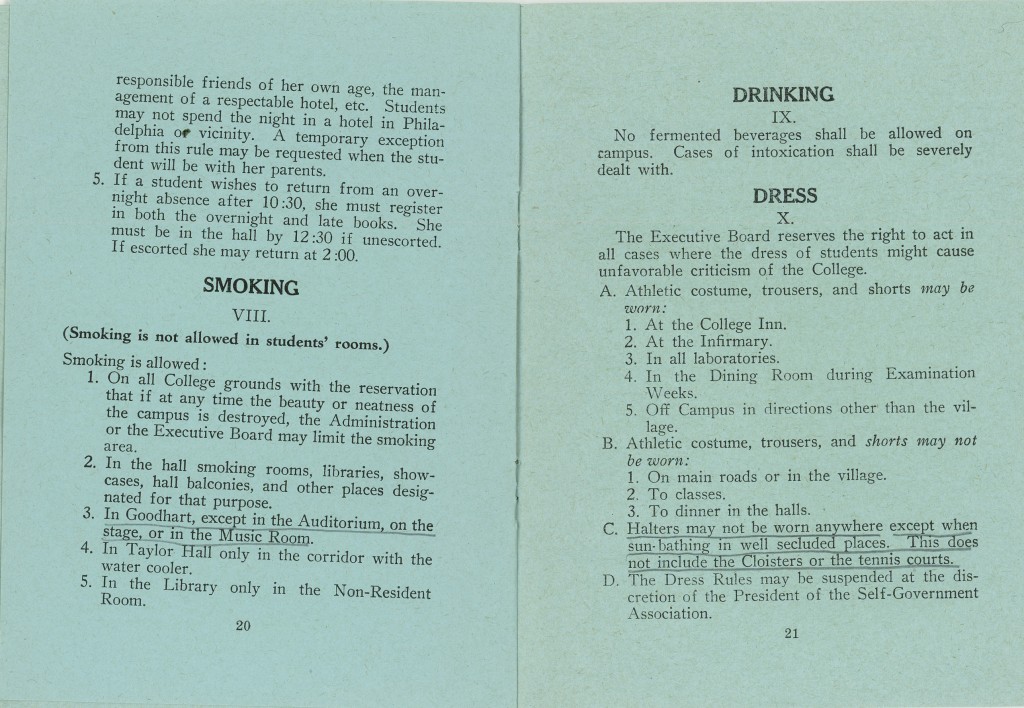

Today, I listened to a speech by Emily Kimbrough, Class of 1921, which she delivered at the Senior Dinner for the Class of 1973. Her speech was riotously funny, and after I finished listening, I decided to look up her alumna file. It turns out that Emily Kimbrough was a very accomplished writer, known for her humorous memoirs and short stories. As if that weren’t fun enough, her breakthrough novel, entitled Our Hearts Were Young and Gay, was co-written with Cornelia Otis Skinner, Class of 1922, a famous writer and actress. The book, published in 1942, is an account of their wild and hilarious trip to Europe when they were fresh out of Bryn Mawr. The book was made into a movie of the same name in 1944, a play dramatized by Jean Kerr, and a short-lived TV show as well. Throughout this process, the book and movie stayed close to their Bryn Mawr roots, with Paramount holding a special Philadelphia premiere of the movie for the Bryn Mawr College Special Scholarship Fund. Special Collections has the program for this premiere, which provides a great glimpse of Bryn Mawr in the 1940’s, as well as the strong associations between Our Hearts Were Young and Gay and the college.

Having discovered this treasure trove of forgotten Bryn Mawr hilarity, I immediately chased down the book and movie for myself. The movie appears to be available in full on Youtube. The book was in Canaday, and I can’t wait to start reading it. Even glancing through it, I can see that it is full of the kinds of Bryn Mawr stories that every Mawrter should adopt into their personal collection of college trivia. I hope that this post can revive the popularity of the book and movie at Bryn Mawr, and perhaps Our Hearts Were Young and Gay will become the new craze to sweep the campus. Such works are invaluable to every Mawrter, since they provide fun glimpses into the lives of our predecessors outside of the classroom. While I get to hear such stories frequently through the oral histories, other students can pick up Our Hearts Were Young and Gay and learn a bit more of the Mawrters of days past, and the mischief they got up to over 90 years ago.

Zoe Fox, 2014