Dr. Jeannette Ridlon Piccard was a pioneer on several fronts in her lifetime. She became the first woman to reach the stratosphere with her husband, Dr. Jean Felix Piccard, in a high-altitude balloon in 1934. In 1974, she became one of the first women ordained as priests by the Episcopal Church. Although she professed little talent for academics, Piccard was a dedicated student. In a letter composed in 1942 as a supplement to a job application, Piccard claimed to have chosen Bryn Mawr College because her high school diploma decreed that she could go to any college in the country except for Bryn Mawr. She wrote, “So I decided to take Bryn Mawr exams so that no one could say there was any college to which I could not go.” Piccard graduated from Bryn Mawr in 1918 with a bachelor’s degree in philosophy and psychology, and went on to earn a master’s degree in organic chemistry from the University of Chicago in 1919, finally receiving her Ph.D. in education from the University of Minnesota in 1942.

The task of organizing her papers, which were donated to Bryn Mawr College by her granddaughter Ruth Elizabeth Piccard, has occupied the bulk of my summer in Special Collections. When I began sorting through the five boxes, I found Piccard’s extensive correspondence mixed with receipts and travel vouchers from her time as a Special Consultant for NASA; drafts of essays on topics ranging from the significance of head covering in various religious denominations to the ethics of modern medicine; evidence of her decades-long campaign for the ordination of women jumbled up with the original research for her Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Minnesota; and even a rough copy of the first few chapters of her unfinished autobiography. The collection was disorganized, to say the least. However, over the past several weeks, I have managed to consolidate the assorted papers into a formal structure that will guide the more complete organization and description of the collection in the future.

By her own account, Piccard lived an eventful and unconventional life. Born in Chicago, Illinois, on January 5, 1895, she was the next-to-youngest of nine children. At three, she watched her twin sister accidentally set herself aflame and burn to death. By the time she was eleven, Piccard had resolved to become a priest, even though at the time there were no female priests in the Episcopal Church. She was also deeply invested in the sciences; even though her majors were philosophy and psychology, she took all the college courses in physics and chemistry she could. Upon entering graduate school at the University of Chicago during the First World War, Piccard chose to pursue a master’s degree in chemistry, partly to “replace a man for the front,” but also because she believed her degree might lead to permanent employment after the war, as opposed to the temporary positions most of her fellow female students expected. It was as a graduate student that Jeannette met her future husband, Swiss national Dr. Jean Felix Piccard. “We were drawn to each other the first time we met. We had the same name. We were [identical] twins.” They married shortly after Jeannette received her degree and promptly left for Switzerland.

Drawn into aeronautics by her brother-in-law Auguste, Piccard qualified as a pilot in 1934. In October of the same year, she and Jean ascended by balloon to an altitude of 57,559 ft, reaching the stratosphere through a layer of clouds. Contemporary accounts hailed Piccard as the first woman in space. She and her husband became popular lecturers as a result of their successful flight and toured for many years, until Jean secured a teaching position at the University of Minnesota, one of the first universities to have a department devoted to aeronautical engineering.

A year after Jean’s death in 1963, the director of NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center hired Jeannette as a consultant. She held the position until it was eliminated for reasons of economy in 1970, the same year the General Convention of the Episcopal Church opened the Diaconate to women. From that point onwards, Piccard devoted herself to becoming a priest, a vocation she had never abandoned. She was finally ordained in 1974 alongside ten other women, who together formed the “Philadelphia Eleven”, the first female priests “irregularly” ordained by the Episcopal Church. After extensive debate, the ordinations were regularized on January 1, 1977.

Although Piccard dedicated her life to two fields in which I otherwise have little interest, I have found a great deal to admire in this woman whom I came to know through the papers she left behind. Piccard was a life-long advocate for gender equality in two areas traditionally closed to women: the church and aerospace. Unapologetically committed to eradicating institutionalized sexism in both space exploration and the church that was so dear to her, Piccard was one of those fortunate people who actually managed to make something of her ambitions, making significant progress in both arenas during her lifetime.

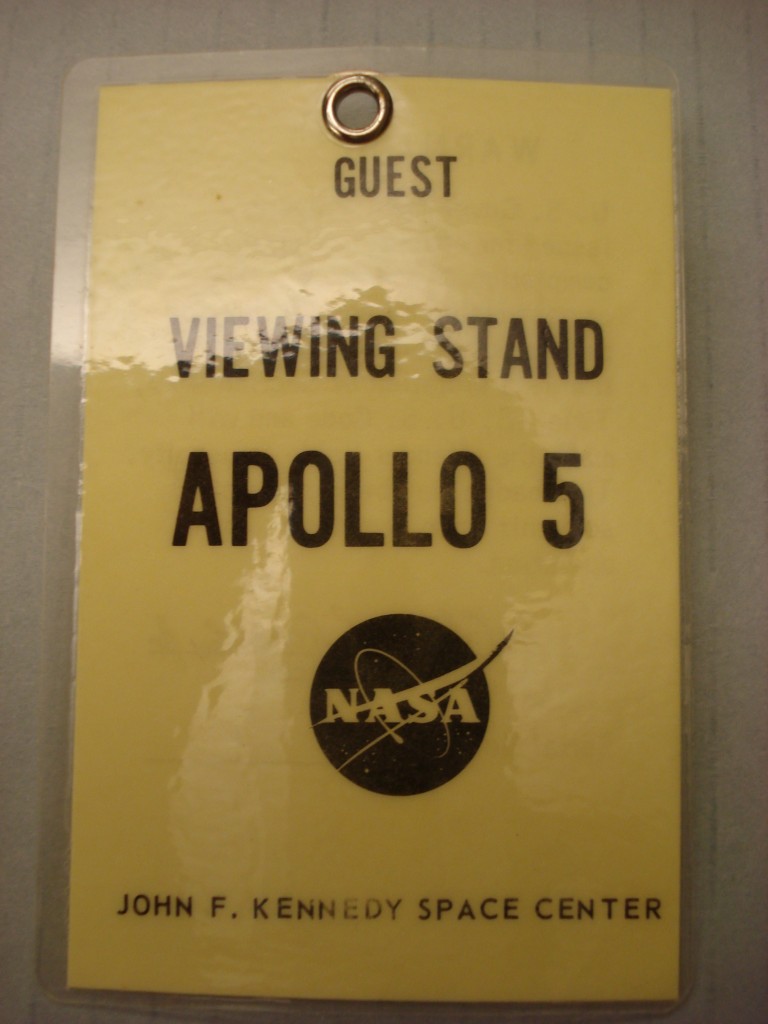

In a letter to a colleague dated March 30, 1970, Piccard noted that she had a number of badges from her time as a Special Consultant for NASA that no longer held any value following the expiration date. “I’ll stick them in the file to edify future generations!” she wrote.

Consider me edified, Reverend Dr. Piccard.