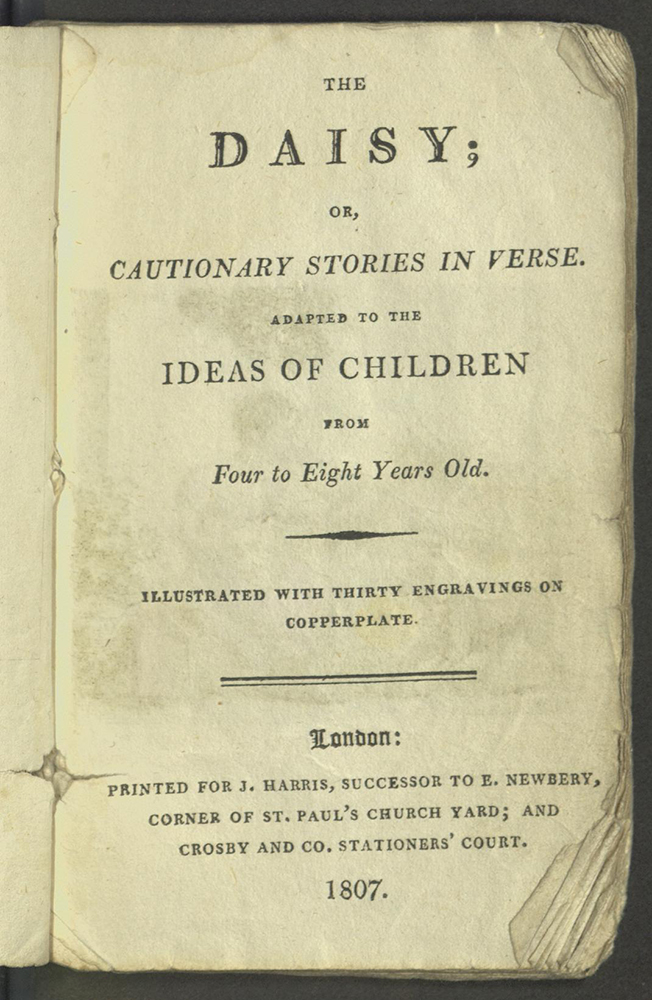

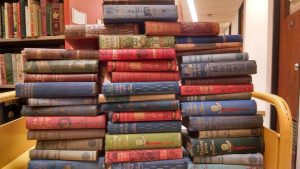

At the beginning of May 2016, the first of 634 boxes of books arrived at the loading dock of Canaday Library. The enormous collection of 19th and 20th-century works for young readers had been bequeathed to the College by Ellery Yale Wood (Class of 1952).

At the beginning of May 2016, the first of 634 boxes of books arrived at the loading dock of Canaday Library. The enormous collection of 19th and 20th-century works for young readers had been bequeathed to the College by Ellery Yale Wood (Class of 1952).

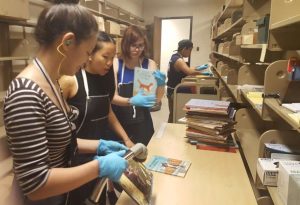

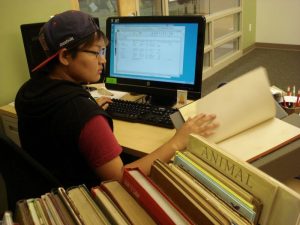

Over the next three months six student employees unpacked, vacuumed, aired out, and roughly sorted approximately 17,000 books.

By the end of that summer, all the books had been sorted and organized by author.

In the succeeding five years, 37 of our student employees have worked on the Wood collection. They alphabetized. They helped identify duplicate volumes. They helped find books to answer reference questions and requests for images – a very difficult task before the books were cataloged and given call numbers. They shelved newly cataloged books, and retrieved and then reshelved books for readers and classes. They put acid-free covers on books with dust jackets, and measured books for the conservation boxes we use for fragile items. Three students – Toby, Kate, and Beck – did preparatory work identifying online records to save our professional catalogers time.

Three of the students who worked on the collection in the first year wrote blog posts – on the Golliwog, Mrs. Molesworth, and Beauty and the Beast.

In addition to the students’ posts, we have blogged about the collection 26 times. This blog is the twenty-seventh.

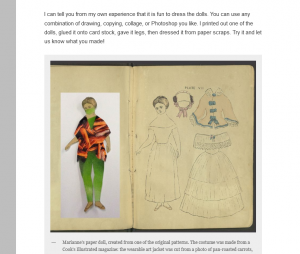

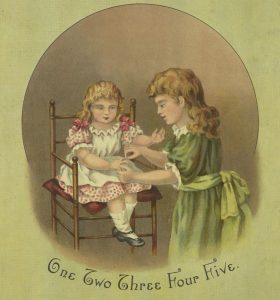

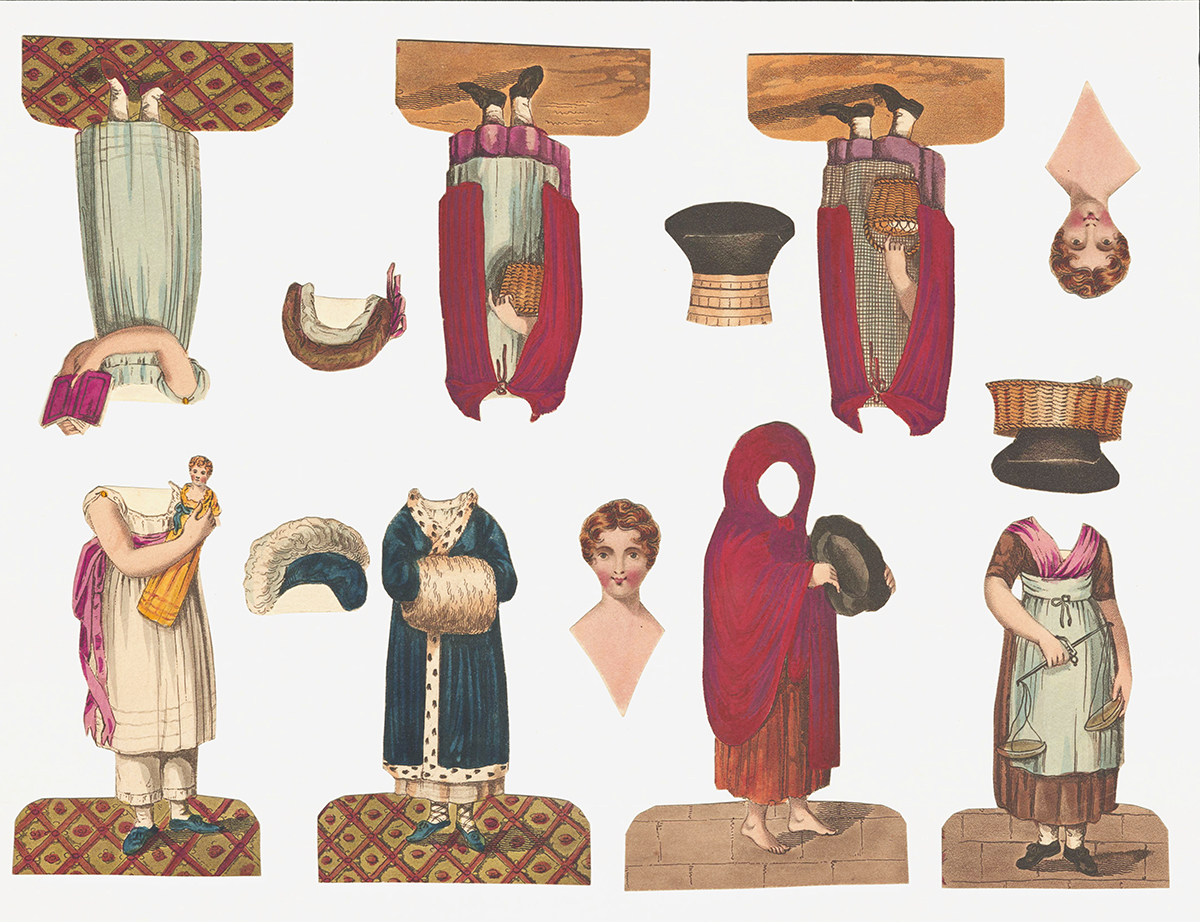

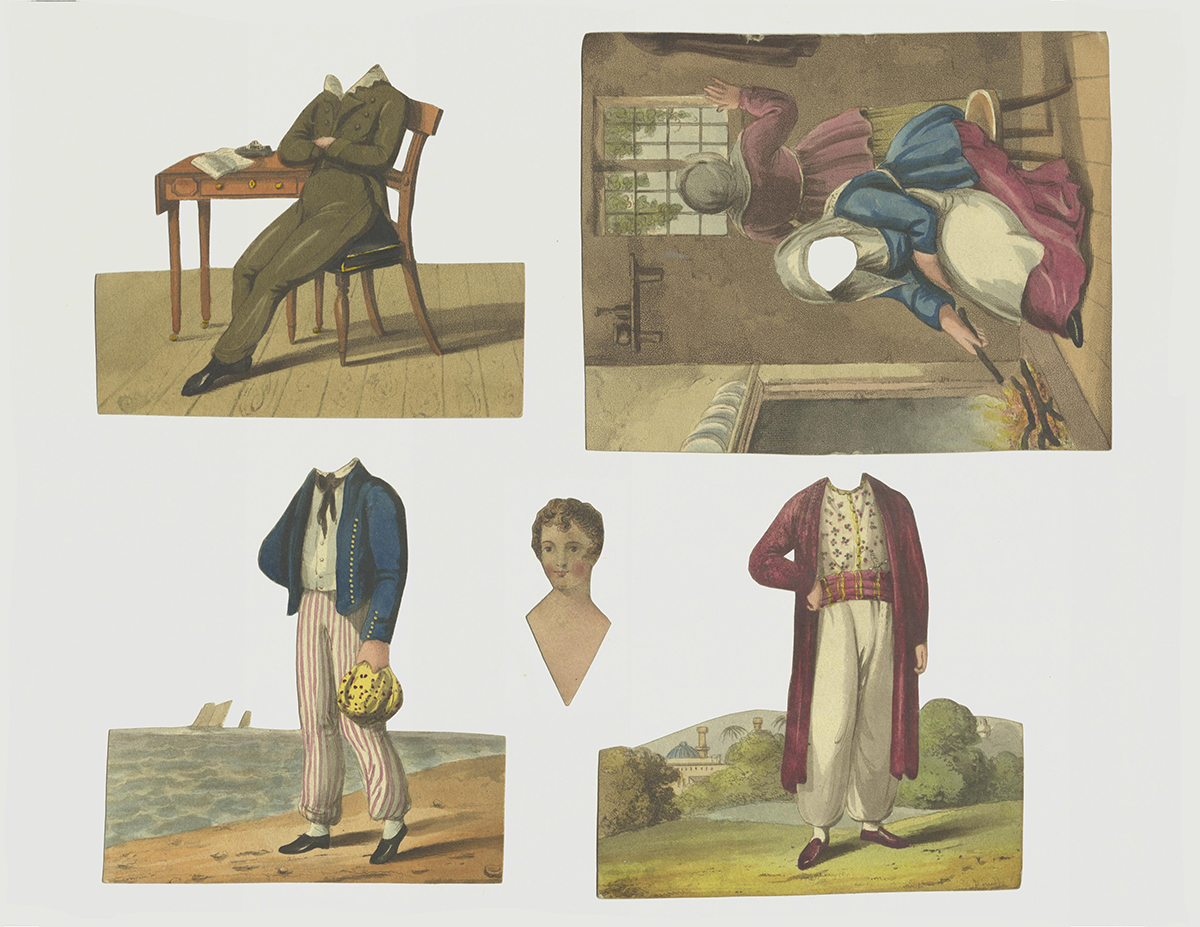

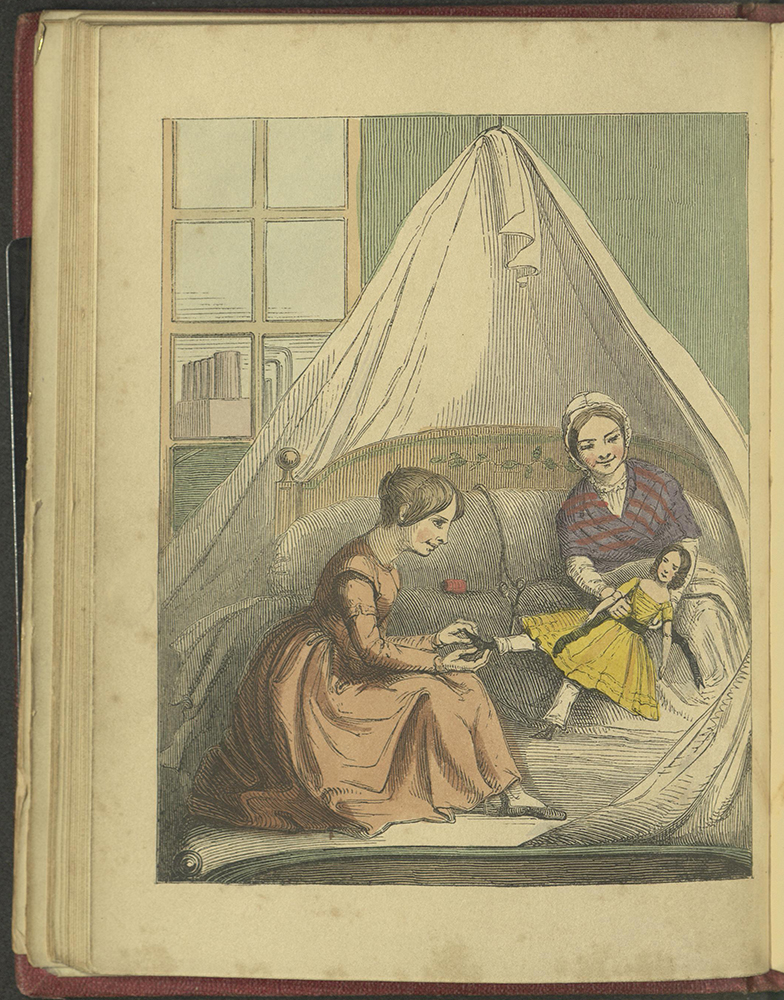

Blog post on Paper Dolls and How to Make Them (1857) with a homemade doll dressed in modern clothing

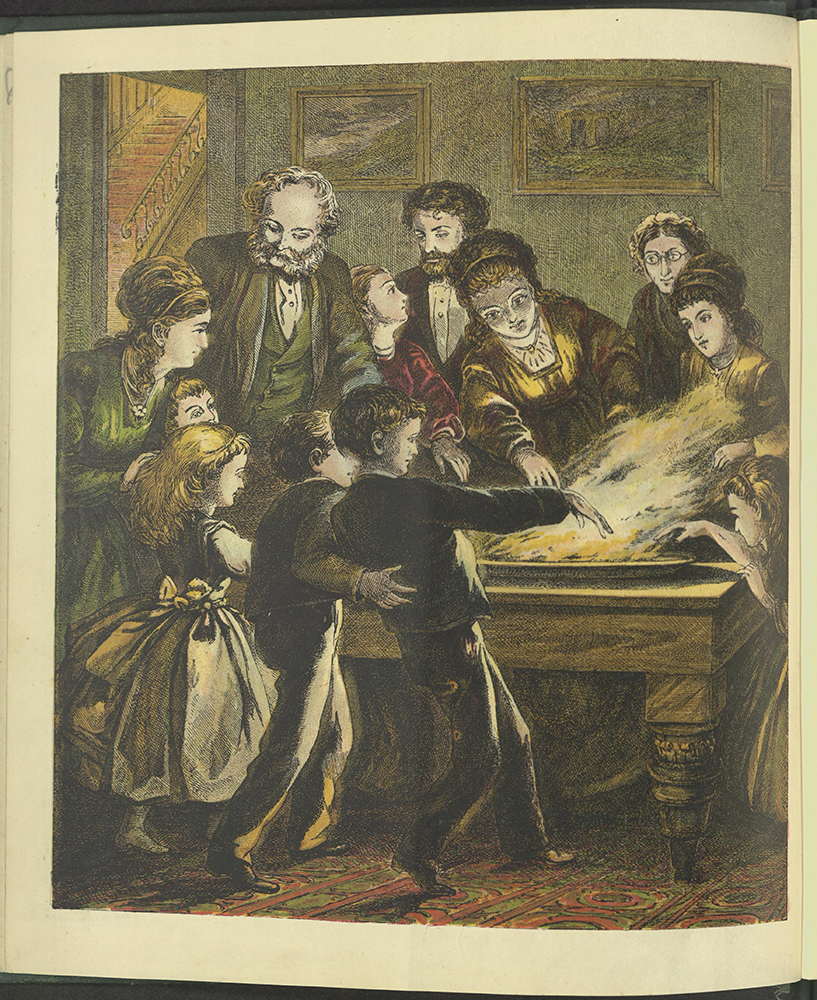

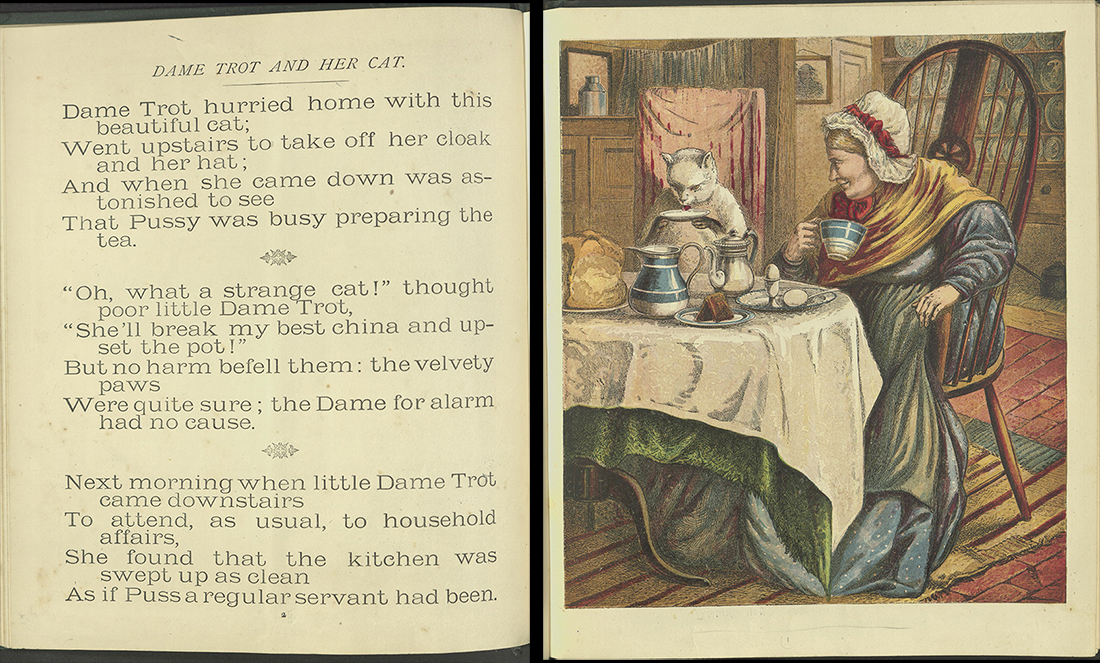

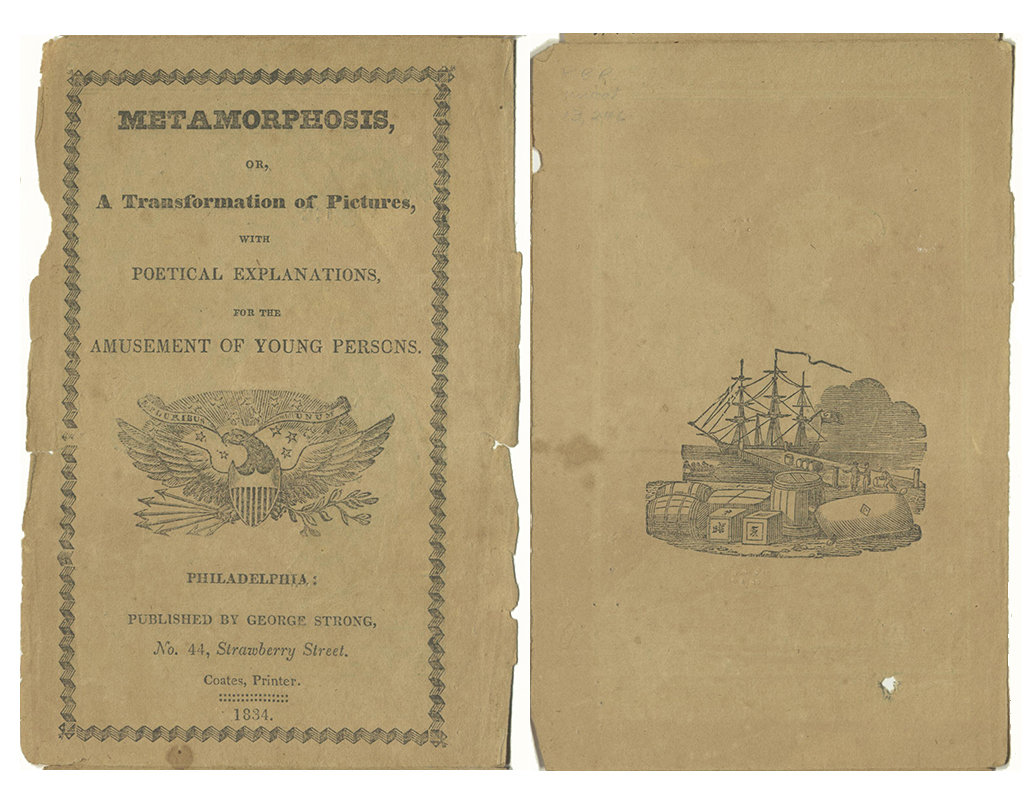

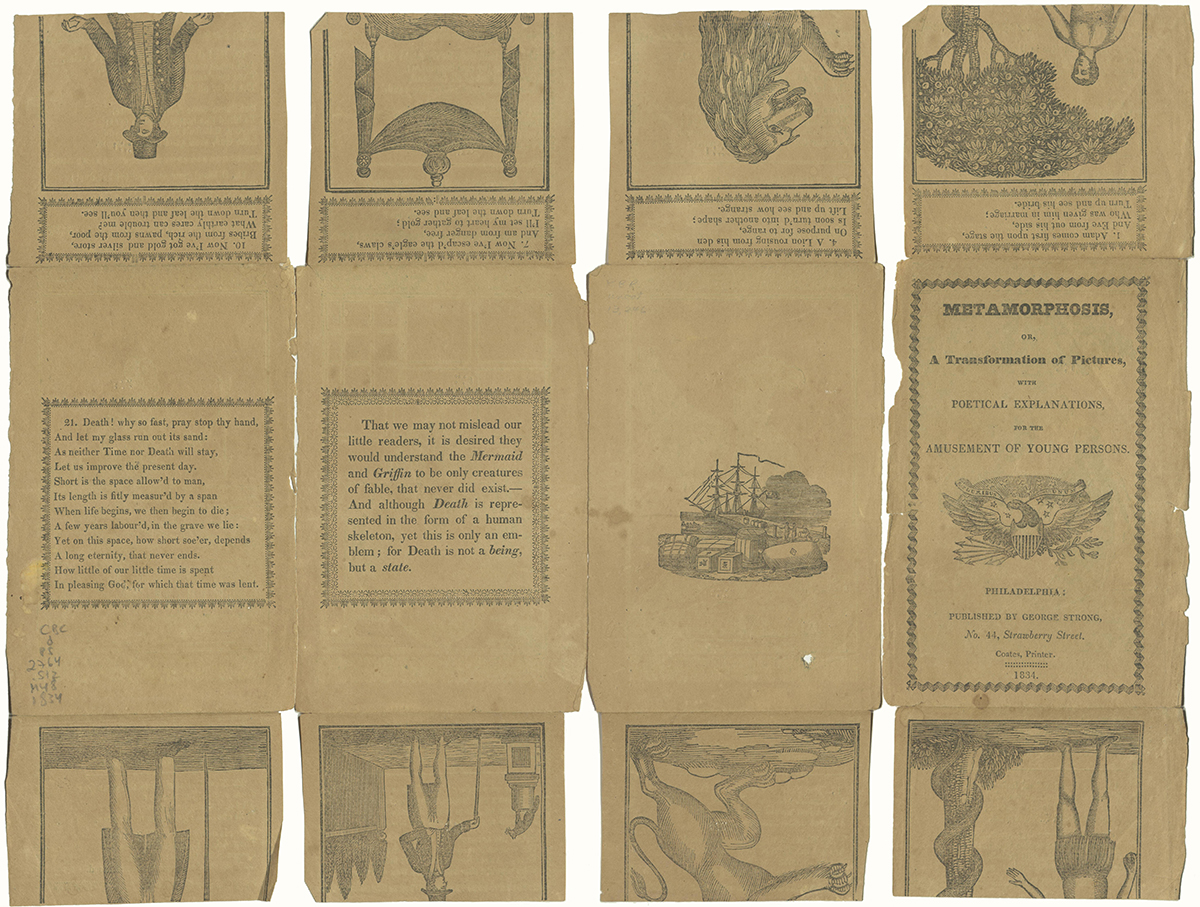

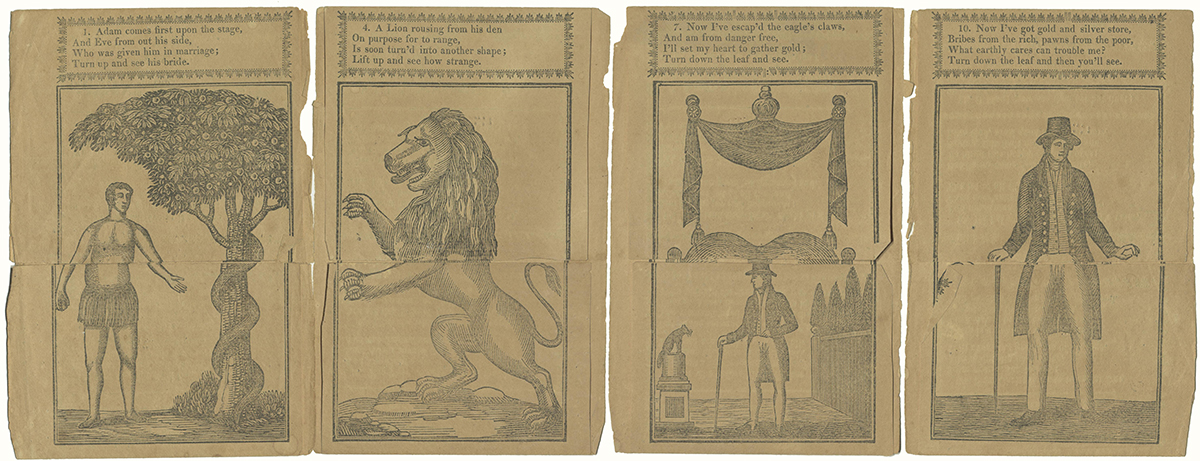

Subsets of the collection – paper dolls, movable books, fairy tales – are large enough to provide significant resources for scholarly research. This year’s Friends of the Libraries intern, Juliet Smith, is the third student to work on the world-class sub-collection of books about Old Dame Trot. We currently have 62 individual historic books and 25 books which include the poem among other texts. Juliet’s efforts will result in an online bibliography and guide by the end of the summer. Two other students are working on Little Goody Two Shoes and The Butterfly’s Ball – and all of their imitators and derivative works.

The collection has been used by 28 Bryn Mawr and Haverford classes in our seminar room. Besides English courses, these include first year writing seminars, Russian Literature, Classics, Museum Studies, and History of the Book. In Fall 2018 a 360° cluster centered around children’s literature included English, Creative Writing, and Sociology courses, with classes and individual students using the collection repeatedly.

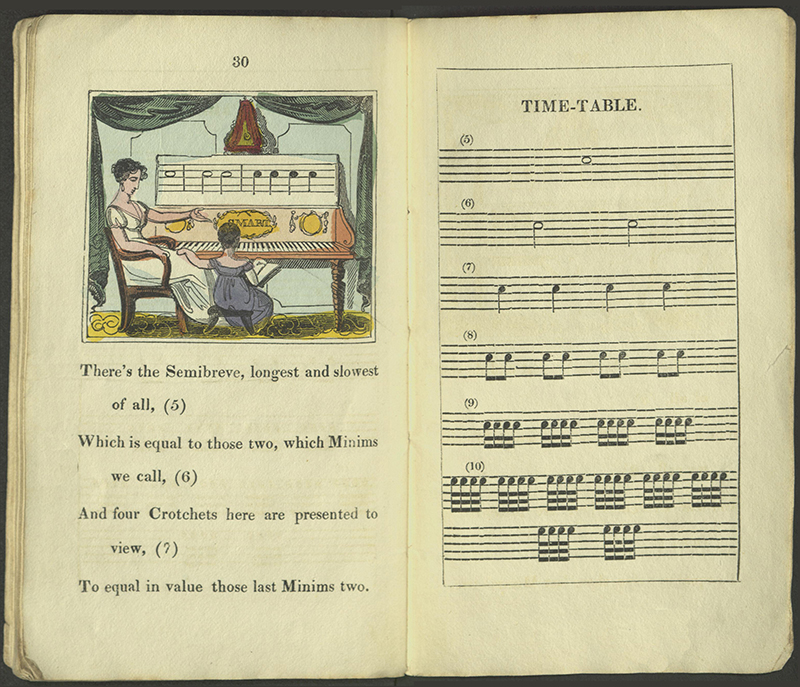

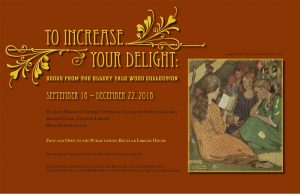

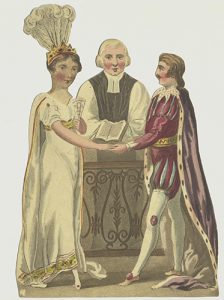

We have presented two exhibitions of these books. To Increase Your Delight introduced the collection to the community in Fall 2016. Four students – Hannah, Isabella, Julia, and Cassidy – spoke on their experiences with the books at an event celebrating the exhibition.

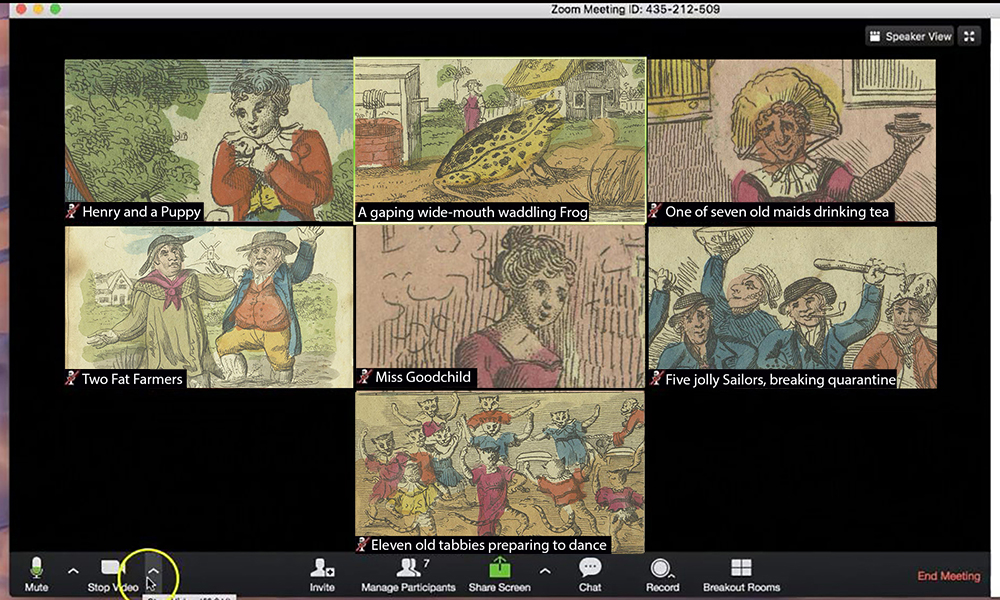

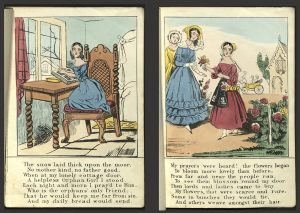

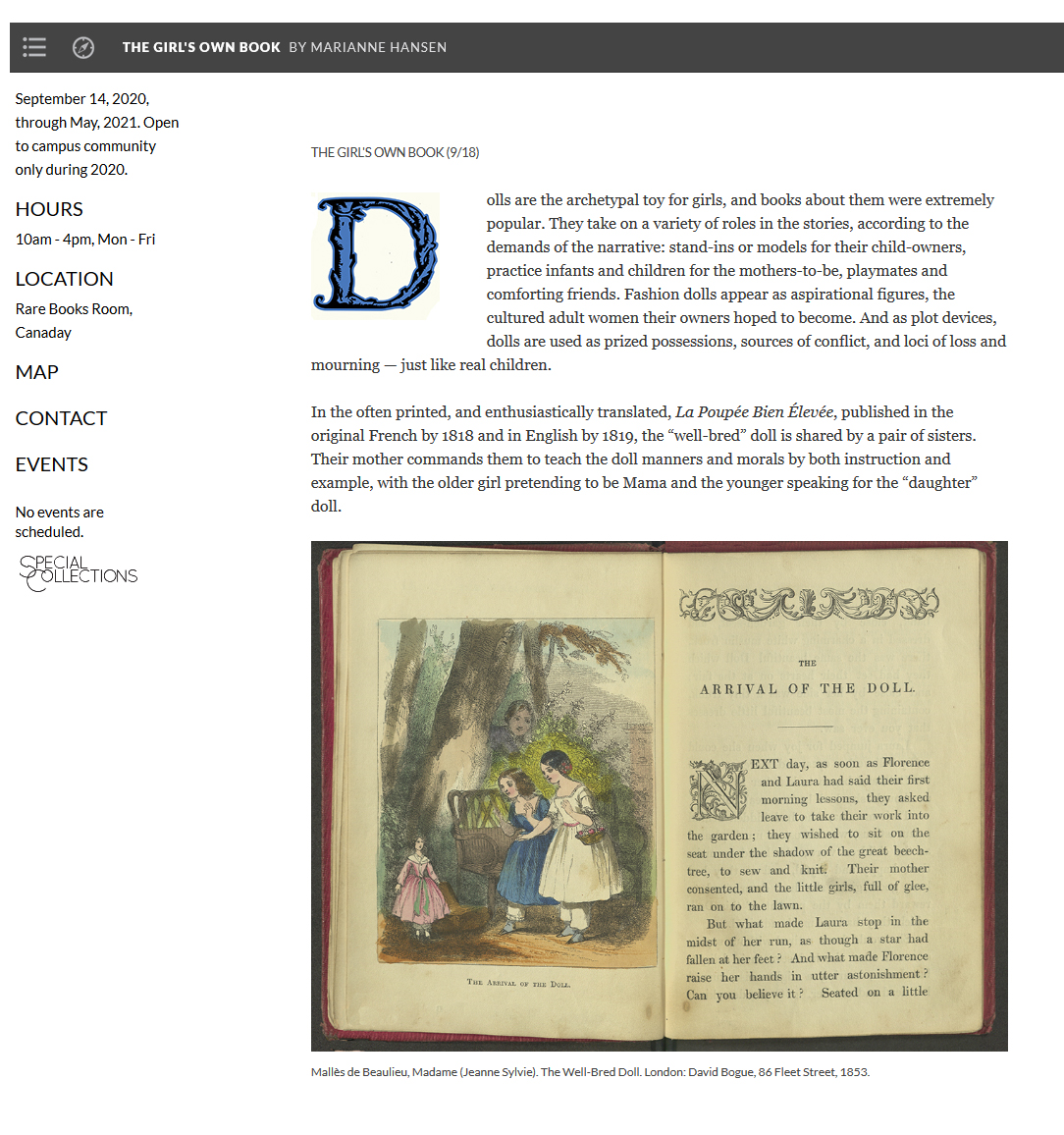

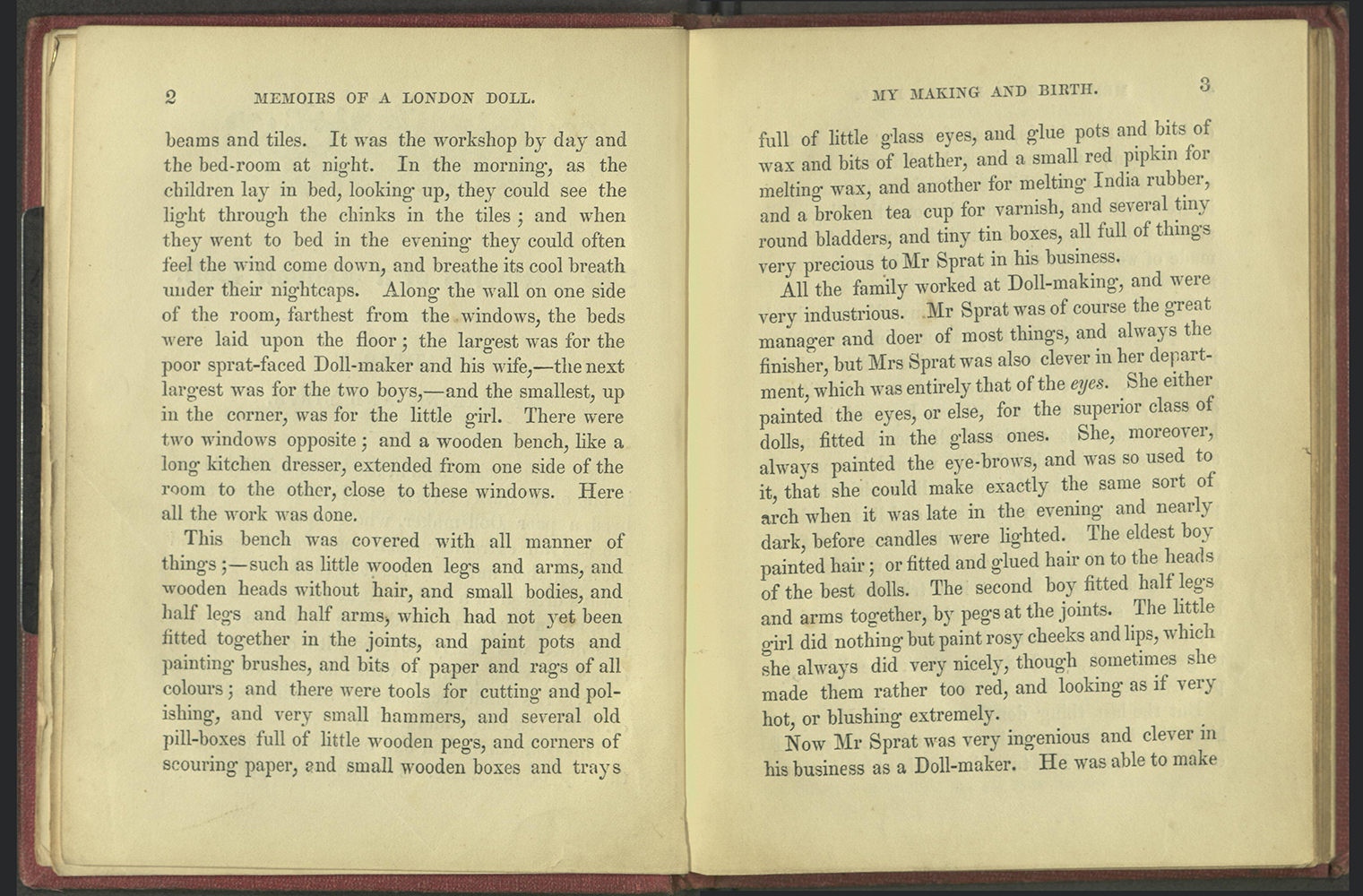

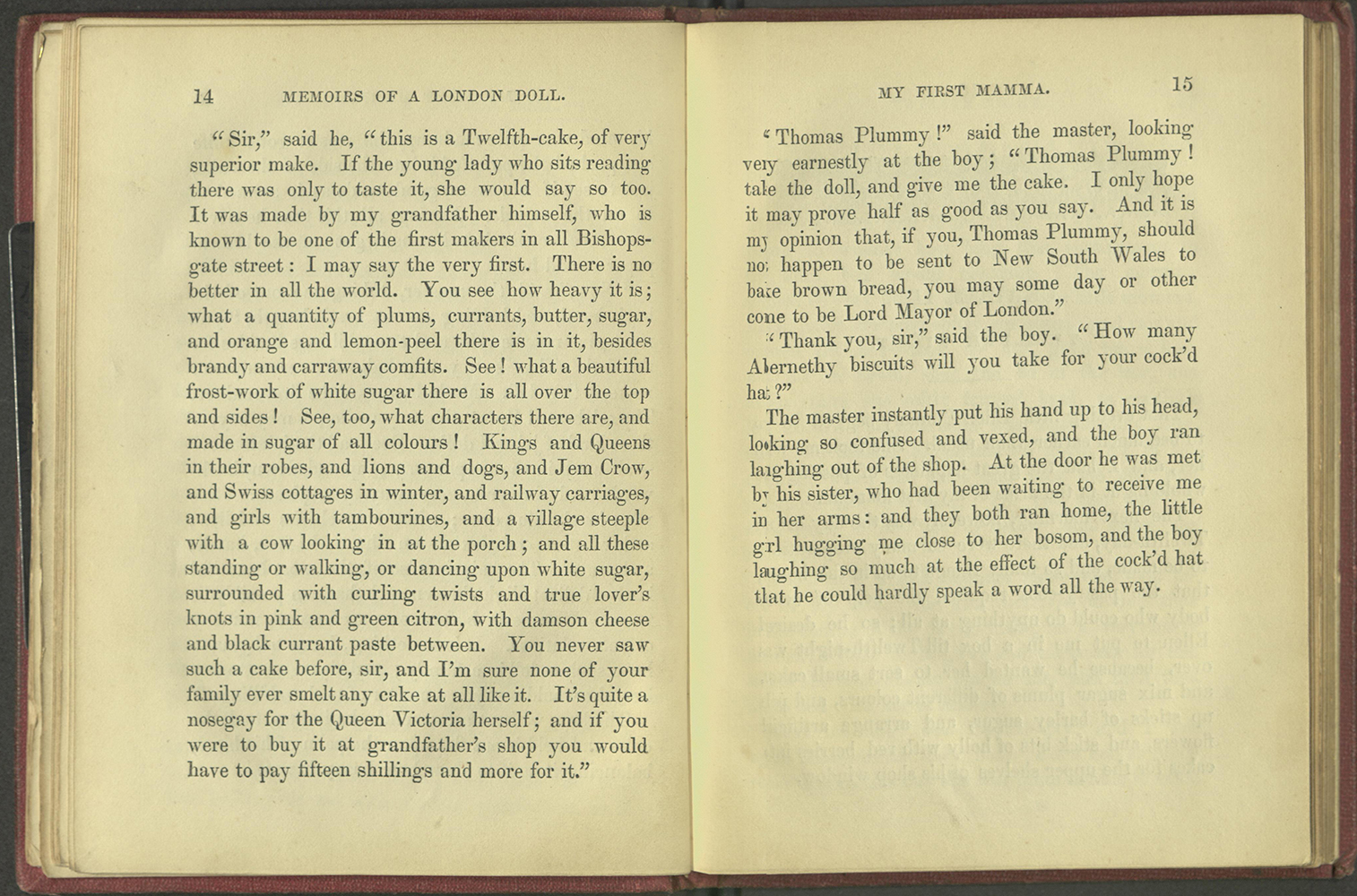

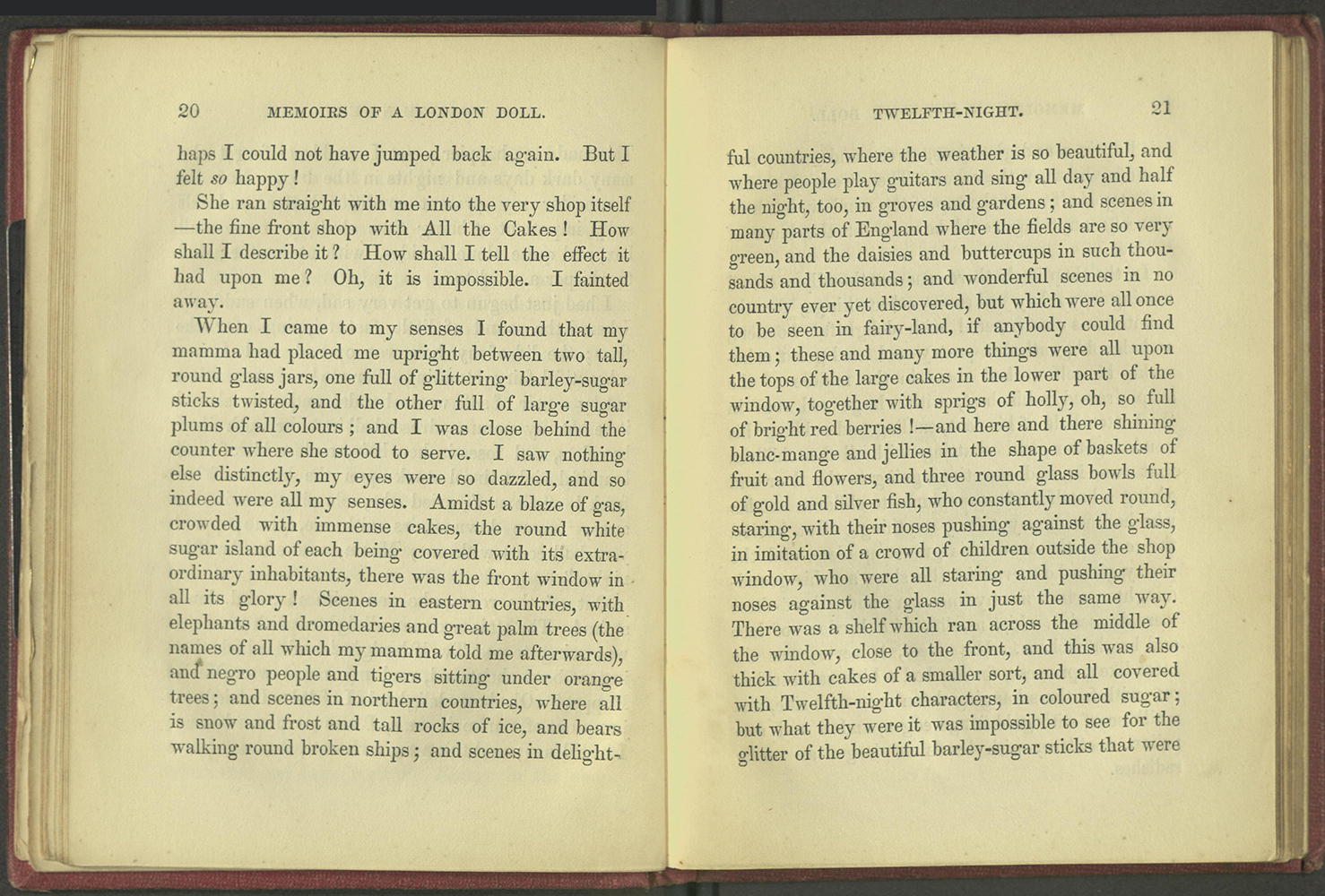

The Girl’s Own Book ran through the 2020-2021 academic year; pandemic restrictions meant that most visitors experienced the show remotely. An online version included the full text of the show and links to online versions of many of the books.

The Girl’s Own Book ran through the 2020-2021 academic year; pandemic restrictions meant that most visitors experienced the show remotely. An online version included the full text of the show and links to online versions of many of the books.

Six students did background research and wrote draft labels for The Girl’s Own Book. Four helped install the show.

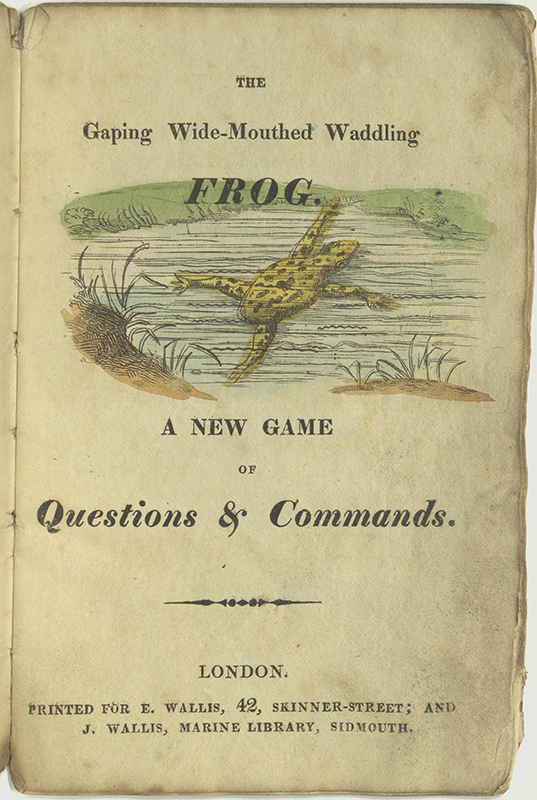

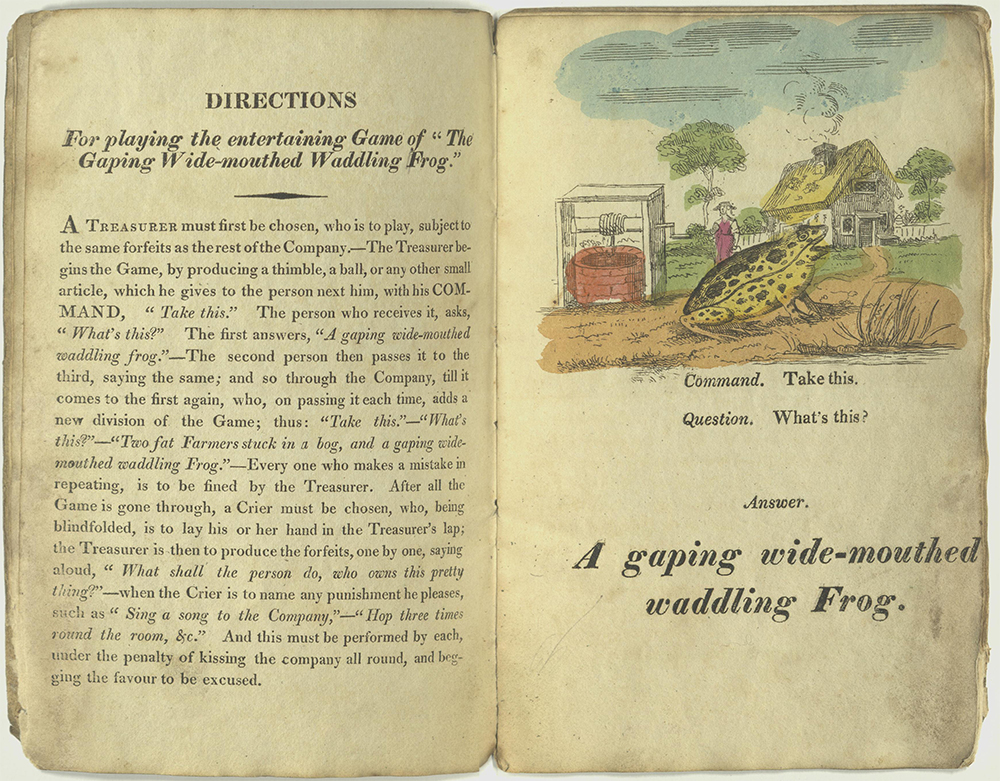

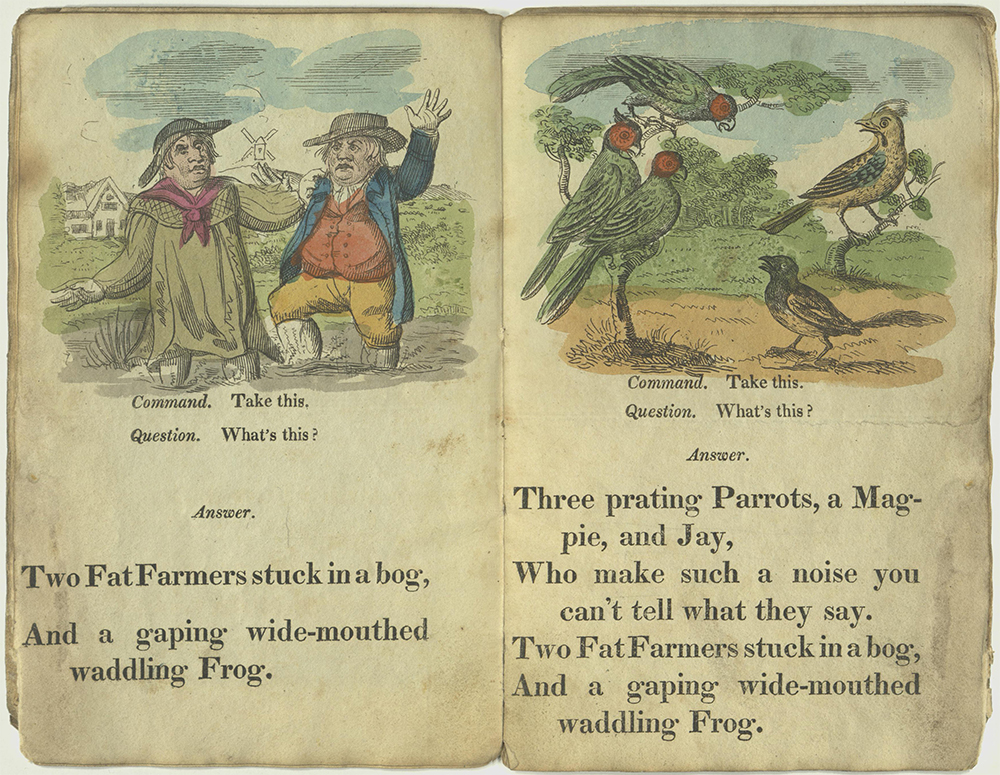

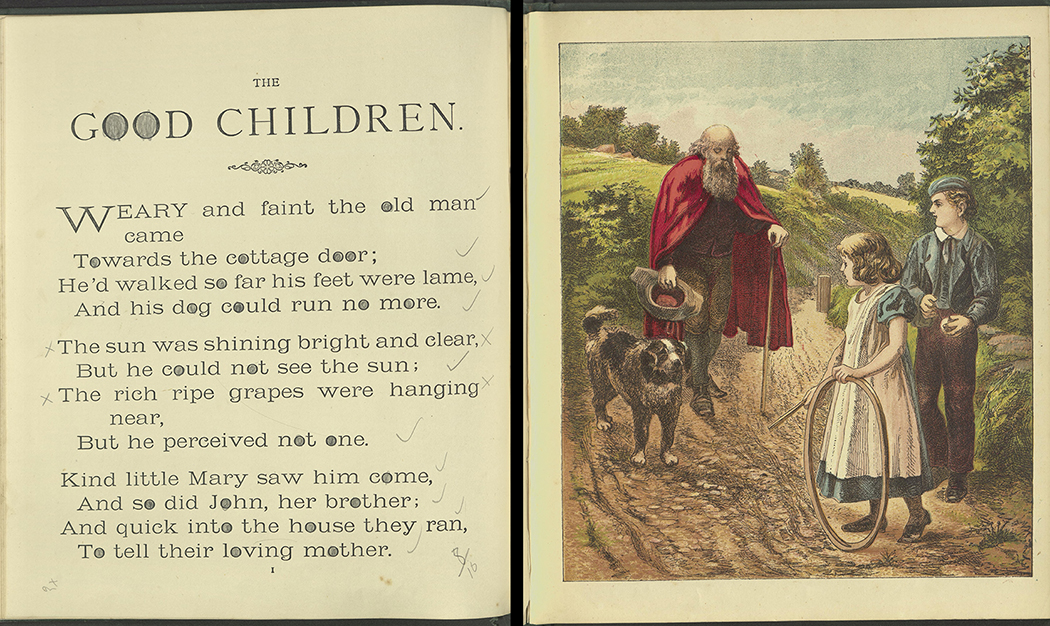

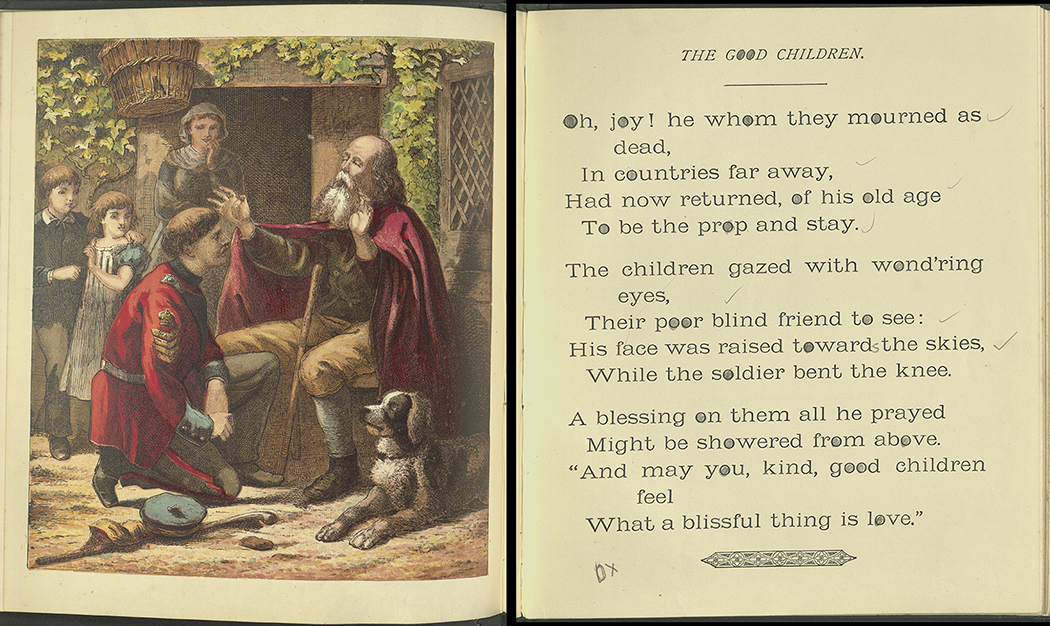

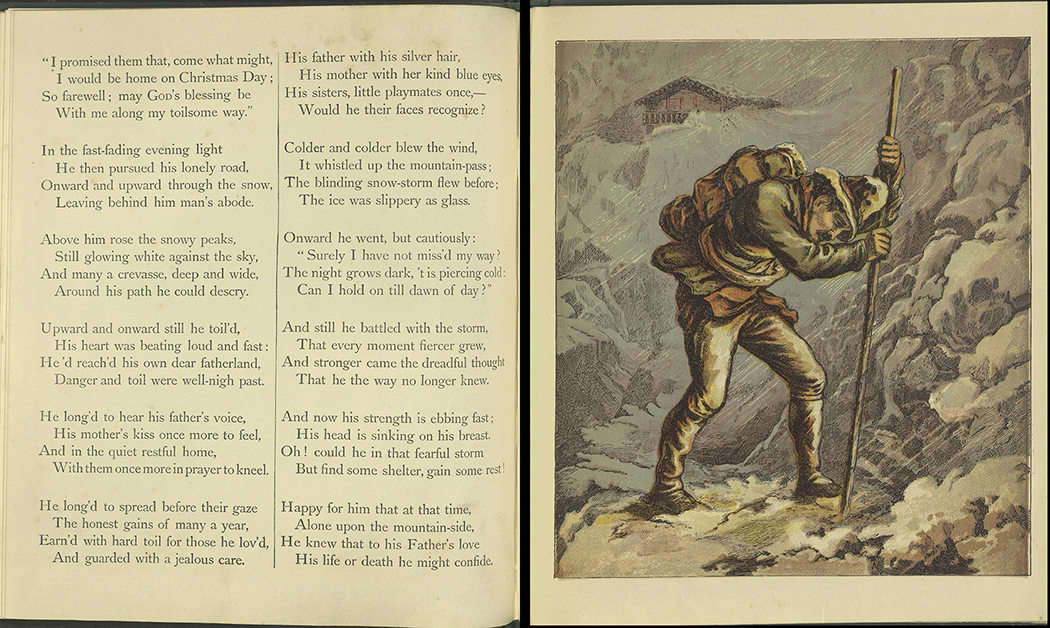

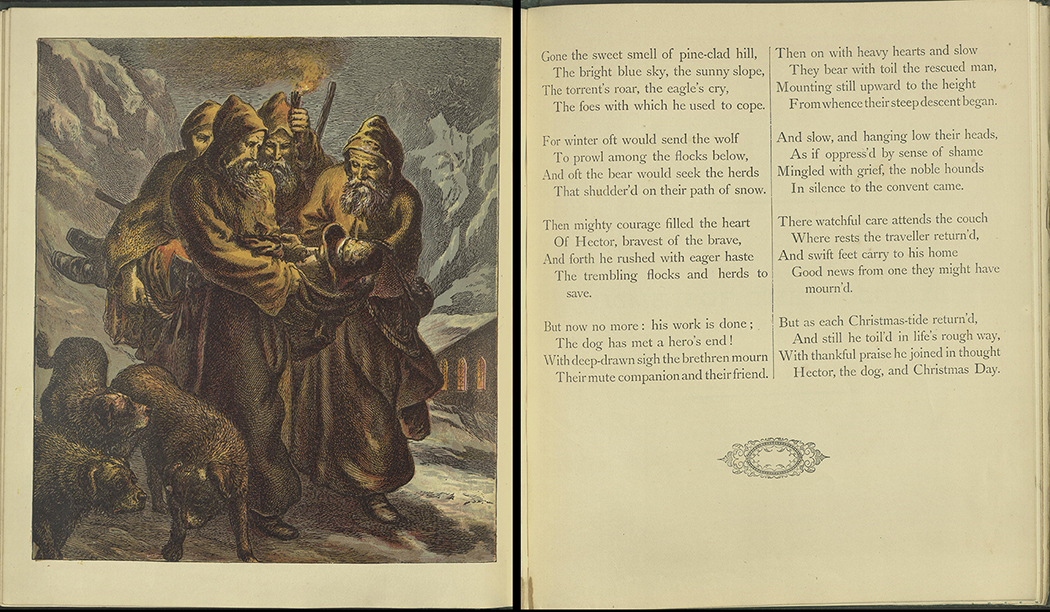

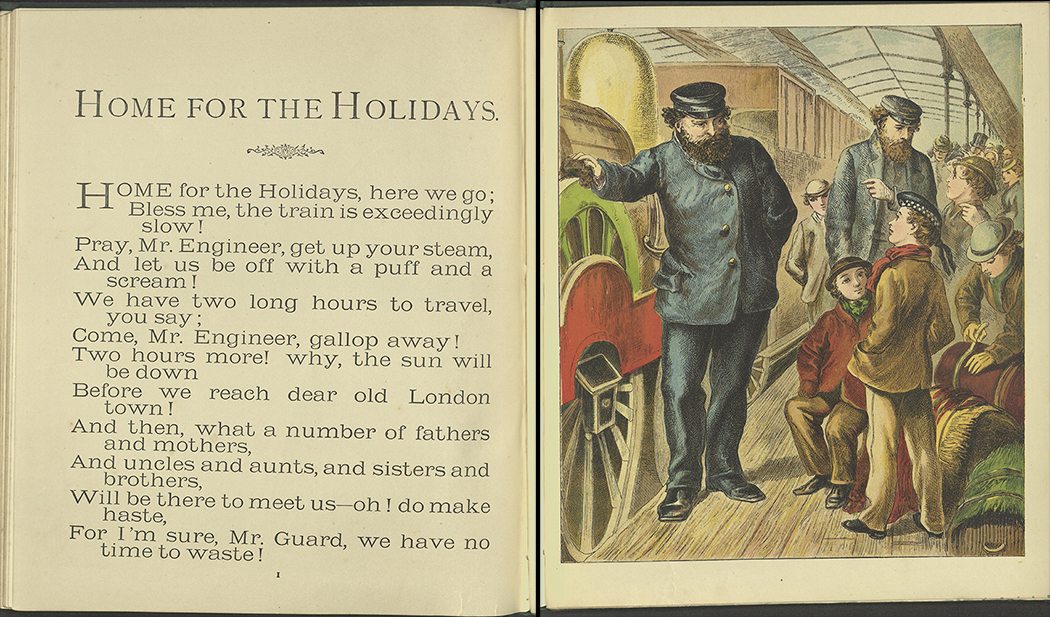

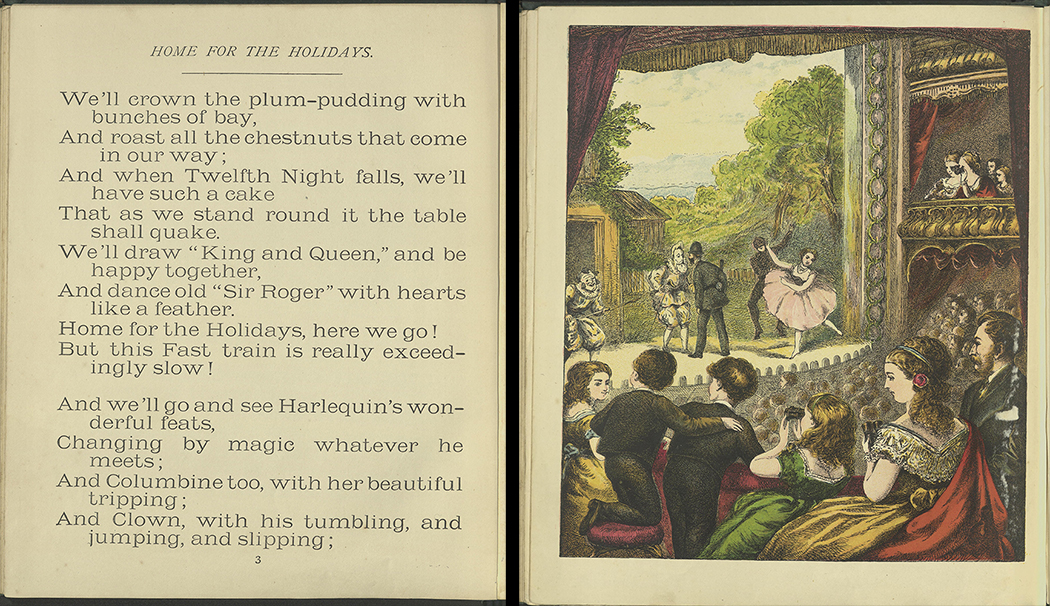

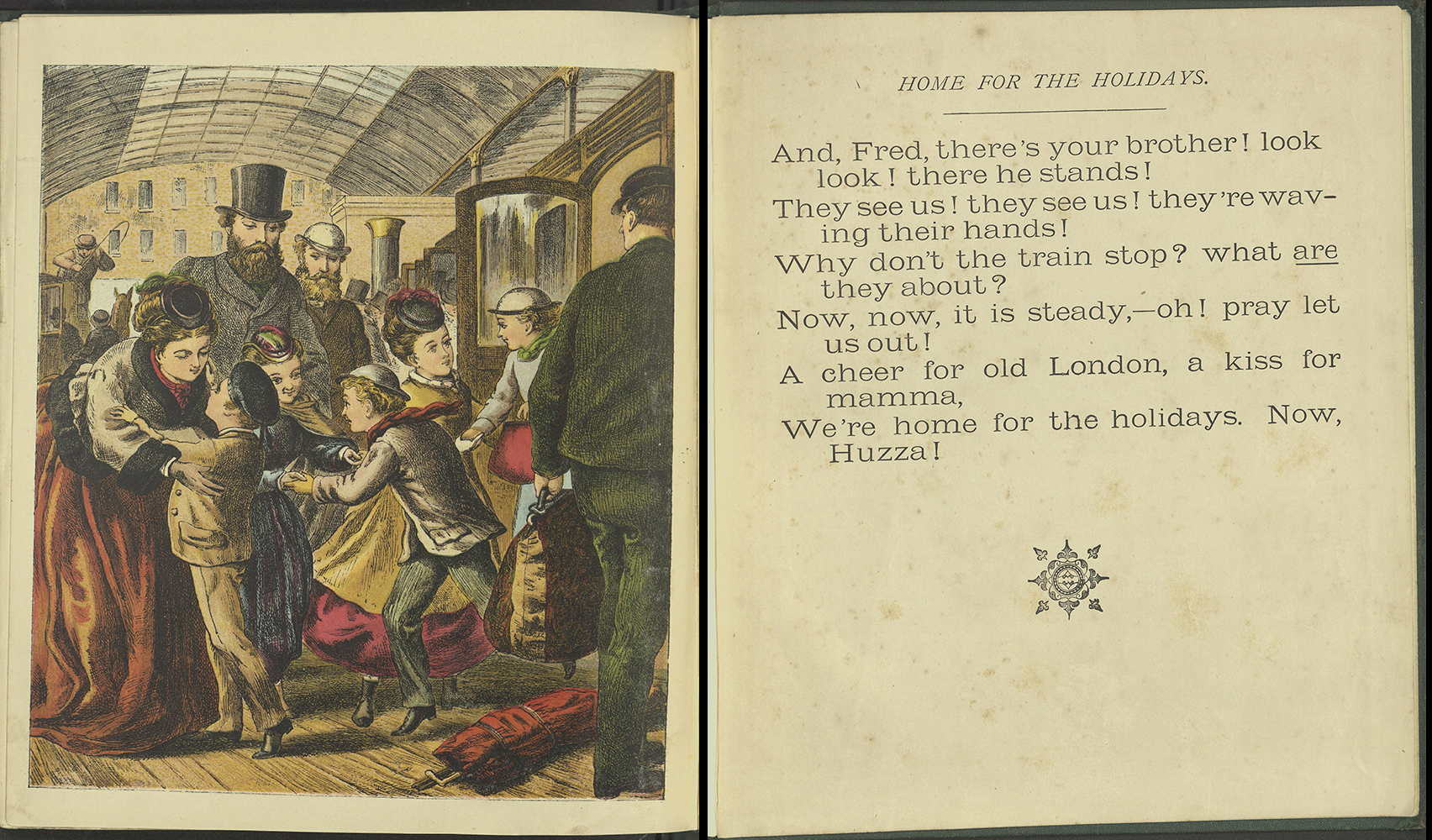

To date, 42 books from the Wood Collection have been fully digitized and shared globally on the Internet Archive. Because it is time-consuming, we digitize only works in the public domain that are not otherwise freely available.

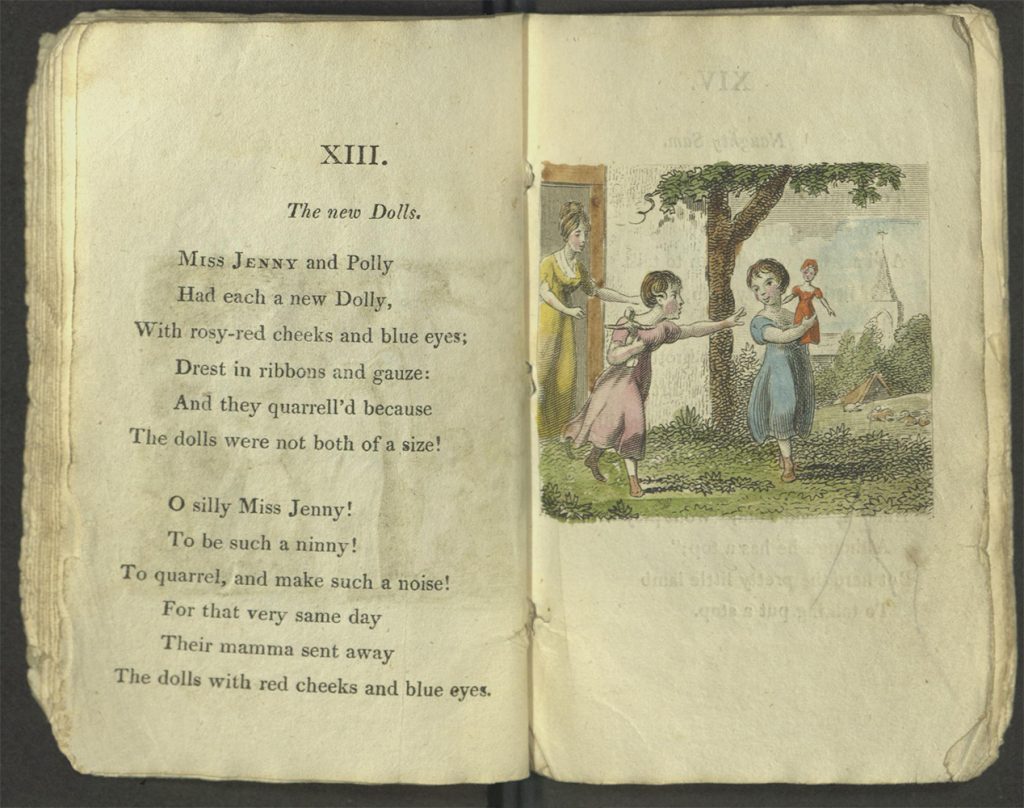

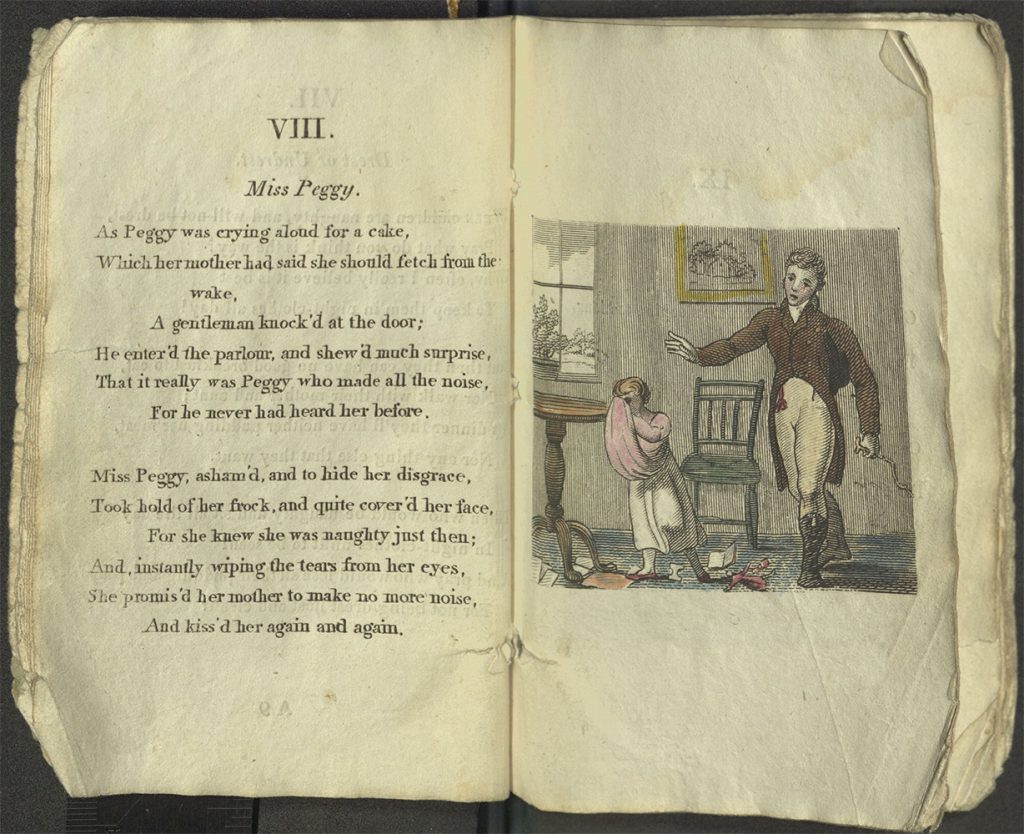

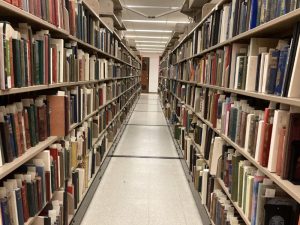

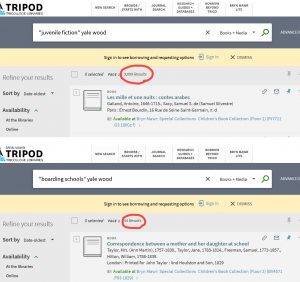

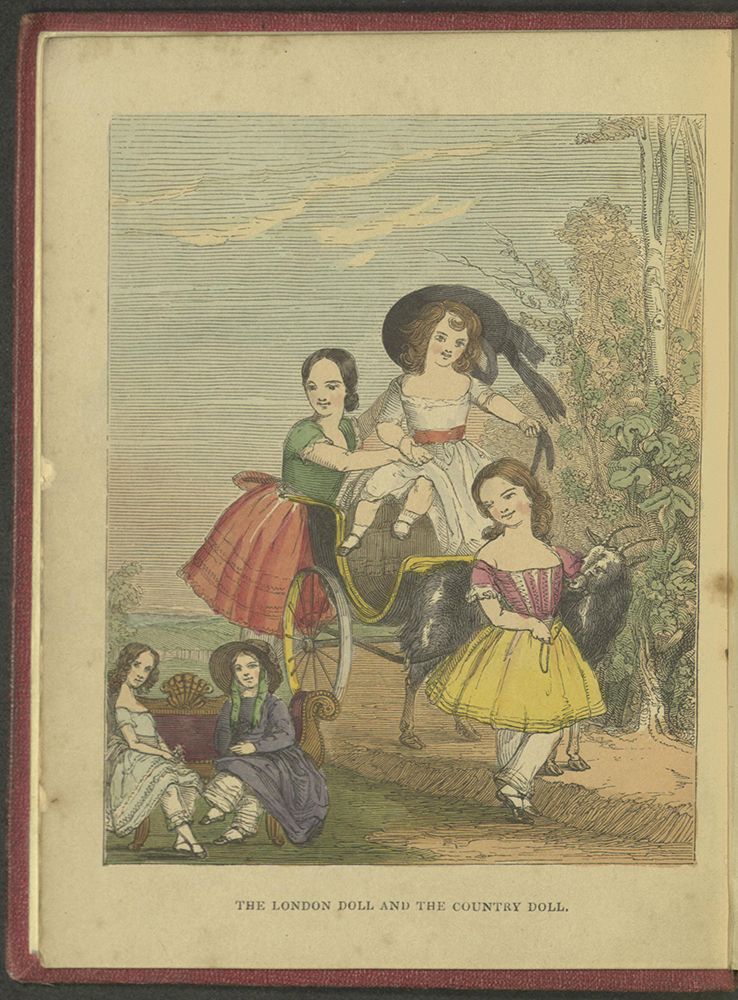

The most strenuous effort in processing any donation of books is cataloging – describing the books and entering them into the library’s public catalog. Historically, fiction – even children’s fiction – has been added to catalogs with little or no information about the major themes in the stories. In cataloging the Wood Collection we broke with tradition to include extensive lists of topics (“subject headings” in library-speak) in the catalog records. So books are not just described as “Juvenile literature”, but with terms like Problem children, Siblings, Orphans, Child labor, Dolls, Boarding Schools, Dreams, Imaginary Voyages, Imperialism, Stereotypes, Adaptations. This deep cataloging has made it possible for students, staff, faculty, and researchers to use Tripod (our online catalog) find books on topics of interest – impossible to do otherwise in a collection of 13,000 books.

Three catalogers and three cataloging assistants have worked on the collection. In the first two years Patrick Crowley, Katharine Chandler, Jo Dutilloy (BMC 2017), and Rayna Andrews (BMC 2011), working part-time, added records for 2750 books.

Starting in 2018, a generous gift from Ellen Michelson (P’09) and additional support from the Friends of the Bryn Mawr College Libraries made it possible to hire a full-time cataloger and a part-time assistant to work exclusively on the Wood Collection. Amy Graham and Maria Gorbunova together cataloged 10,811 books before their appointments ended March 31, 2021. Maria worked primarily on 20th-century books, although her extensive language skills helped us add Russian, Japanese, French, and German titles as well. Cataloger Amy Graham managed the cataloging project and concentrated on the earlier volumes.

Nearly 600 of the catalog records Amy created were “original” – she was not able to use another library’s description for the book, but needed to catalog it from the beginning based on the book itself and her research on its publisher, author, date, and contents.

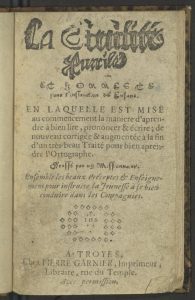

La civilité puérile et honneste pour l’instruction des enfans (1736) – one of the books Amy cataloged “from scratch”

As of June 2021, there were 13,402 books cataloged in the Ellery Yale Wood Collection.

The collection is still growing. Curator Marianne Hansen has taken over cataloging, to make information about additional books accessible. A relatively small number of books from the bequest still need to be added to Tripod. We have recently received three donations of twentieth-century picture books for young readers, totaling 125 books. Finally, we buy books to add to our collection – 50 in the last year – and those books must also be cataloged. We look forward to building the collection and making it available to readers for years to come!

The collection is still growing. Curator Marianne Hansen has taken over cataloging, to make information about additional books accessible. A relatively small number of books from the bequest still need to be added to Tripod. We have recently received three donations of twentieth-century picture books for young readers, totaling 125 books. Finally, we buy books to add to our collection – 50 in the last year – and those books must also be cataloged. We look forward to building the collection and making it available to readers for years to come!

The Girl’s Own Book is now open online at

The Girl’s Own Book is now open online at

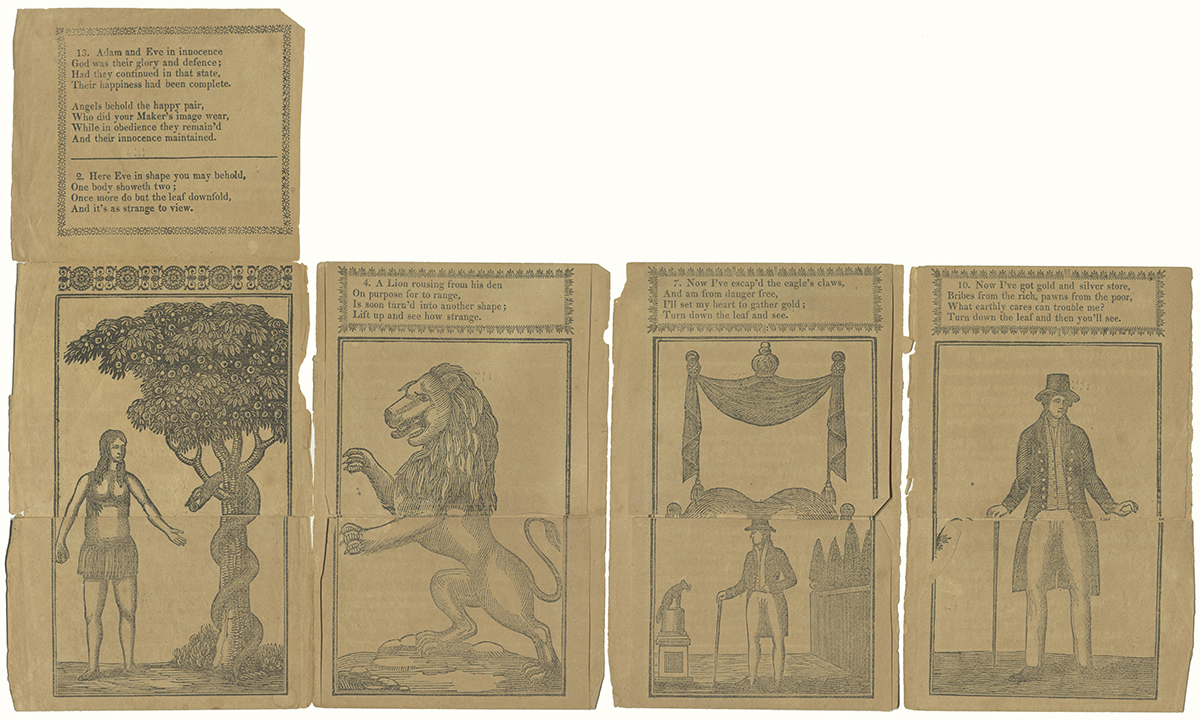

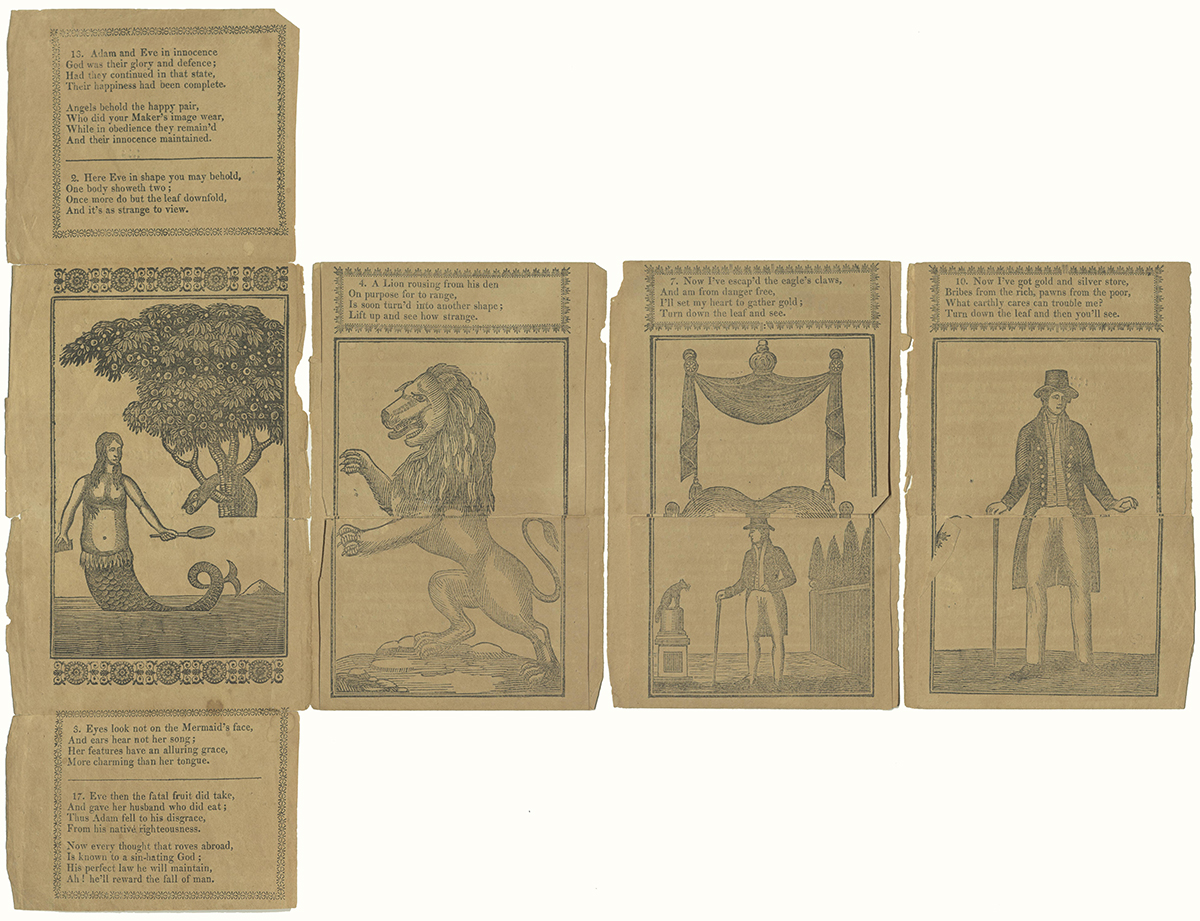

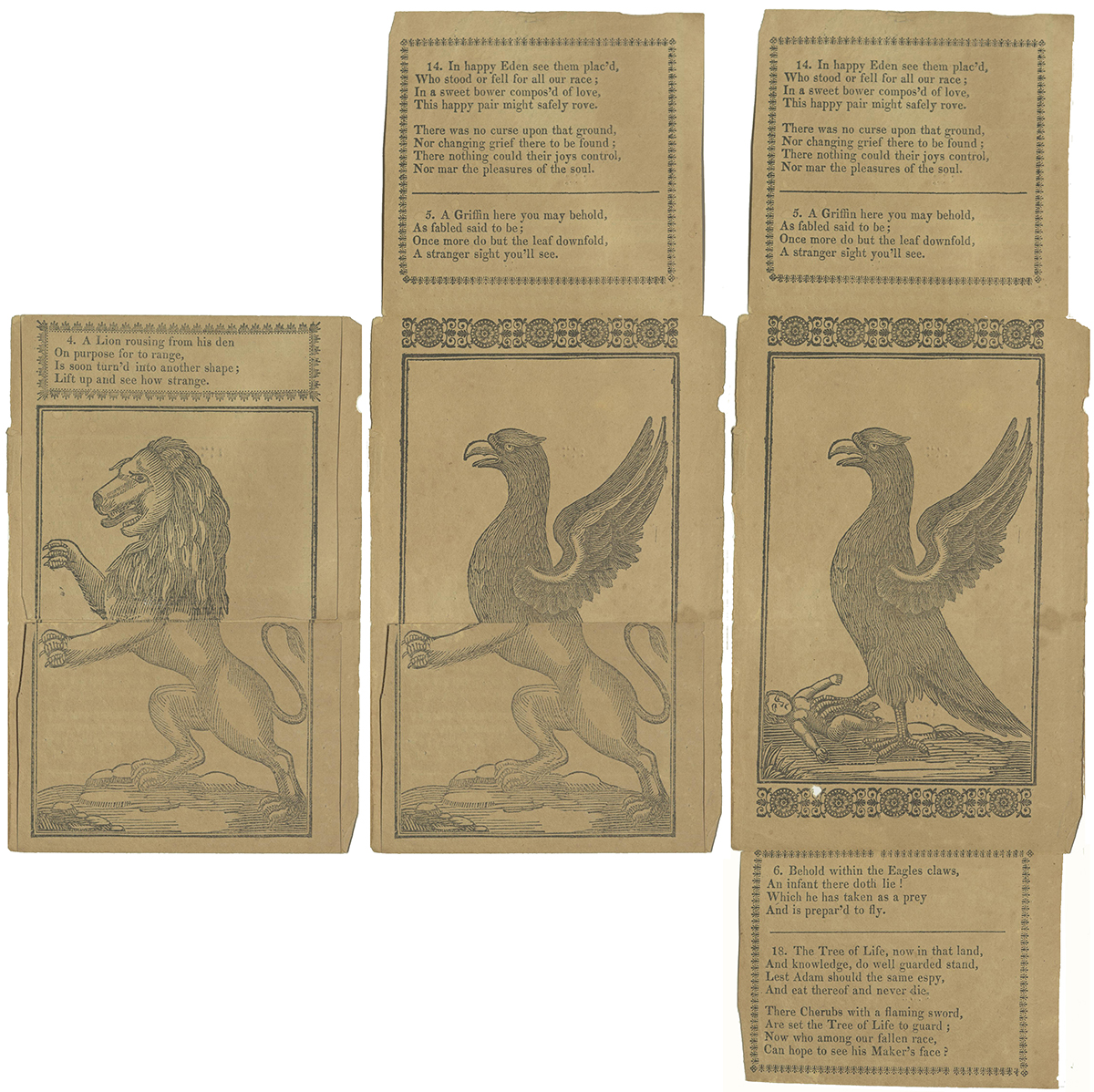

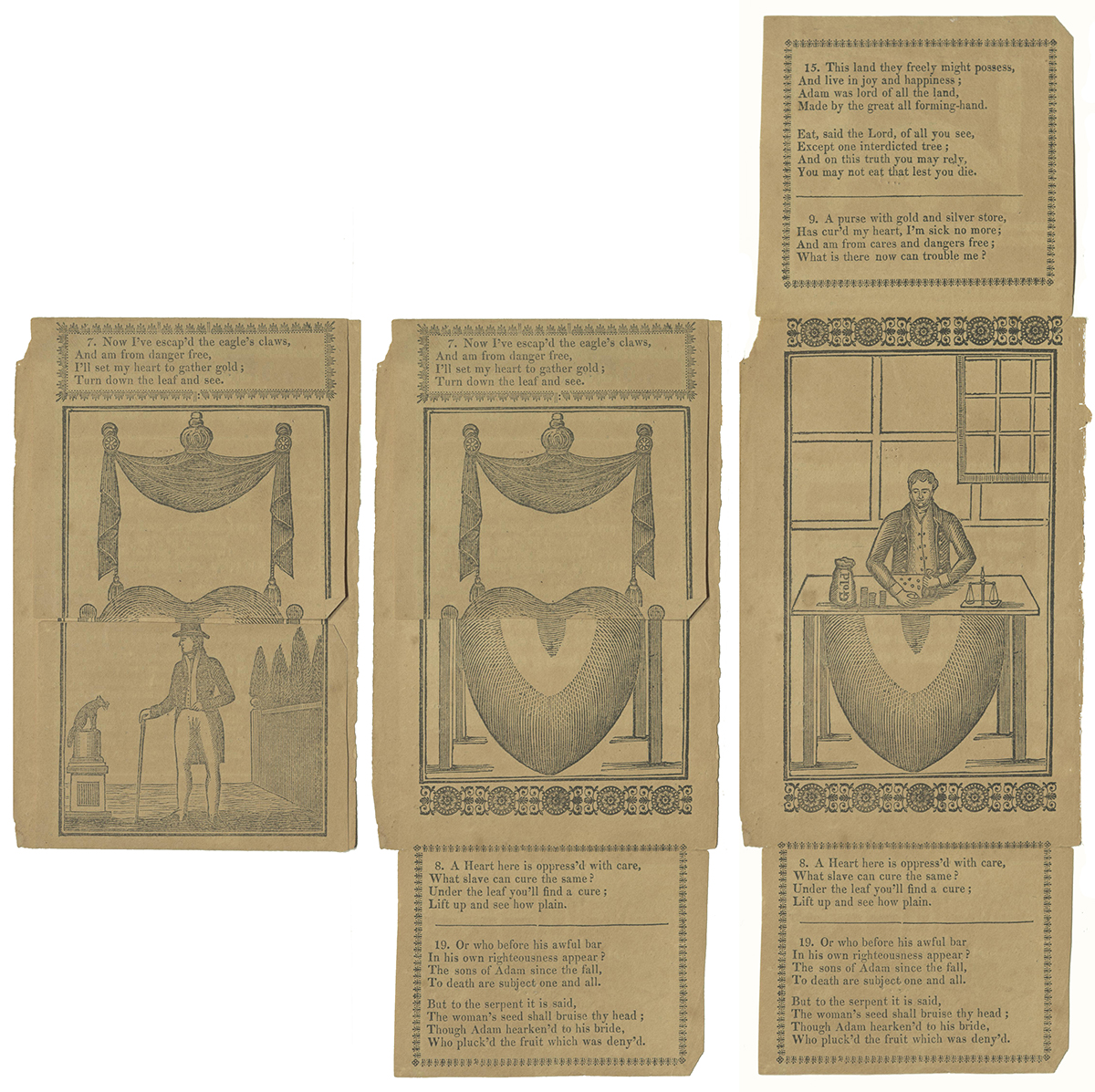

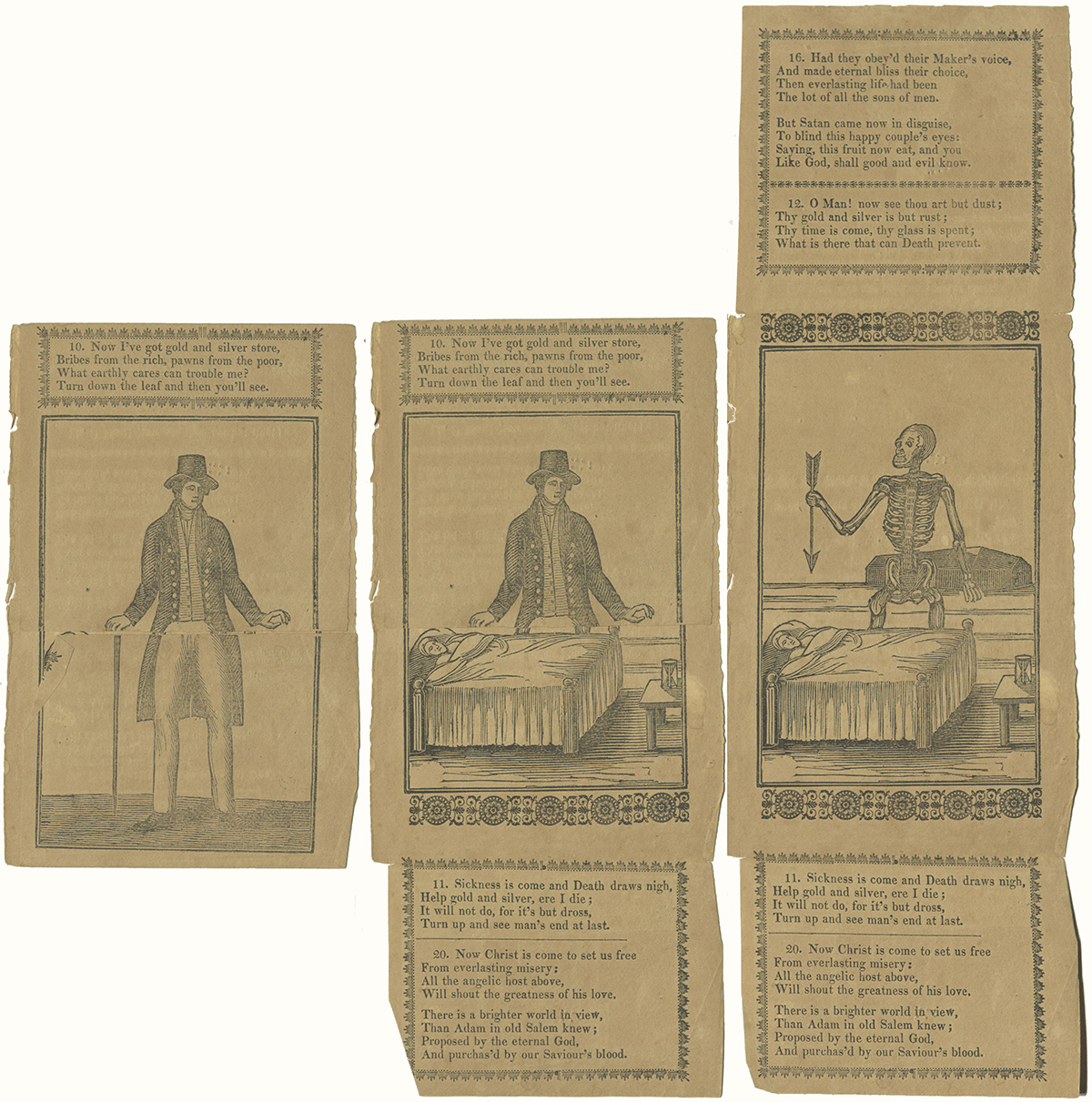

![Verse 13: Adam and Eve in innocence, God was their glory and defence : Had they continued in that state, Their happiness had been complete. Angels, behold the happy pair, Who did your Maker’s image wear, While in obedience they remain’d And their innocence maintained. Verse 14: In happy Eden see them plac’d, Who stood or fell for all our race; In a sweet bower, composed of love, This happy pair might safely rove. There was no curse upon that ground, Nor changing grief there to be found: There nothing could their joys controul [sic], Nor mar the pleasures of the soul. Verse 15: This land they freely might possess, And live in joy and happiness: Adam was lord of all the land, Made by the great all-forming hand. Eat, said the Lord, of all you see, Except one interdicted tree; And on this truth you may rely, You may not eat that lest you die. Verse 16 (not numbered): Had they obey’d their Maker’s voice, And made eternal bliss their choice, Then everlasting life had been The lot of all the sons of men. But Satan came now in disguise, To blind this happy couple’s eyes: Saying, this fruit now eat, and you Like God, shall good and evil know.](http://specialcollections.blogs.brynmawr.edu/files/2020/06/13through16.jpg)