“I often tell young ladies, that no excellence in music is to be acquired, without constant practice,” says Lady Catherine de Bourg, in Pride and Prejudice. Anyone who has learned to play an instrument knows that, for once, she is correct, but that practice is not enough. In early 19th-century families of social standing, learning music meant not just playing “by ear”, but also learning to play from printed sheet music.

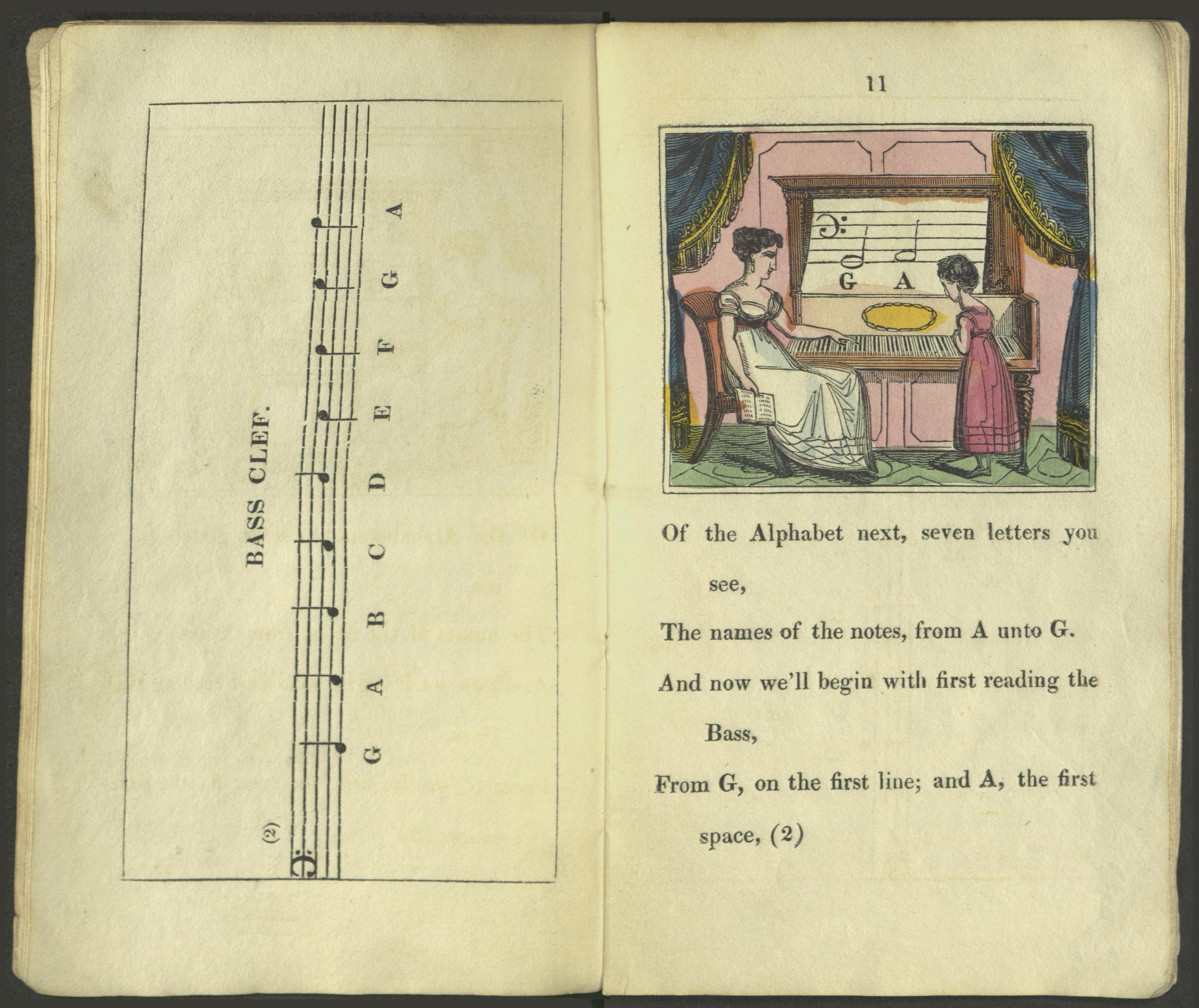

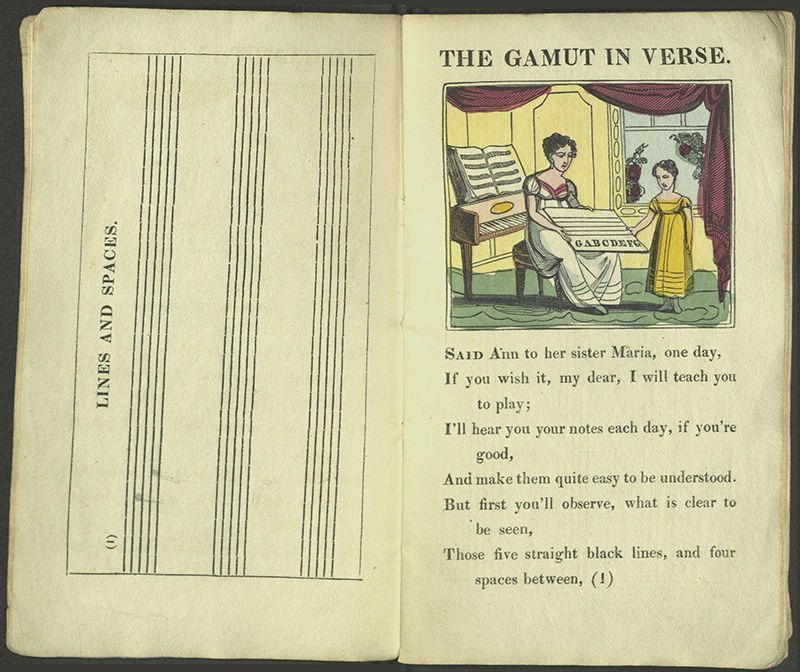

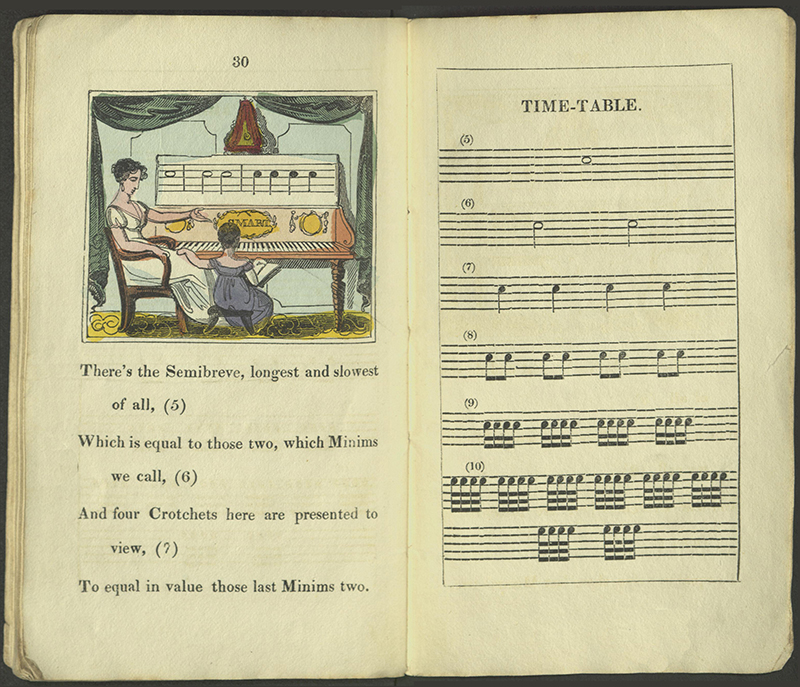

The Gamut and Time-Table in Verse offers a minimal introduction to the notes of the bass and treble clefs, and to the duration of different types of notes, the two most basic skills in reading music. This information is necessary, but far from sufficient. Anyone who learned “Every Good Boy Does Fine” in their first music lesson knows that you soon stop repeating the phrase as you look at the score. How much more so if you had learned, “Then the second space A, is here to be seen,/ The third line is B.–C, the third space between.”

The Gamut and Time-Table in Verse offers a minimal introduction to the notes of the bass and treble clefs, and to the duration of different types of notes, the two most basic skills in reading music. This information is necessary, but far from sufficient. Anyone who learned “Every Good Boy Does Fine” in their first music lesson knows that you soon stop repeating the phrase as you look at the score. How much more so if you had learned, “Then the second space A, is here to be seen,/ The third line is B.–C, the third space between.”

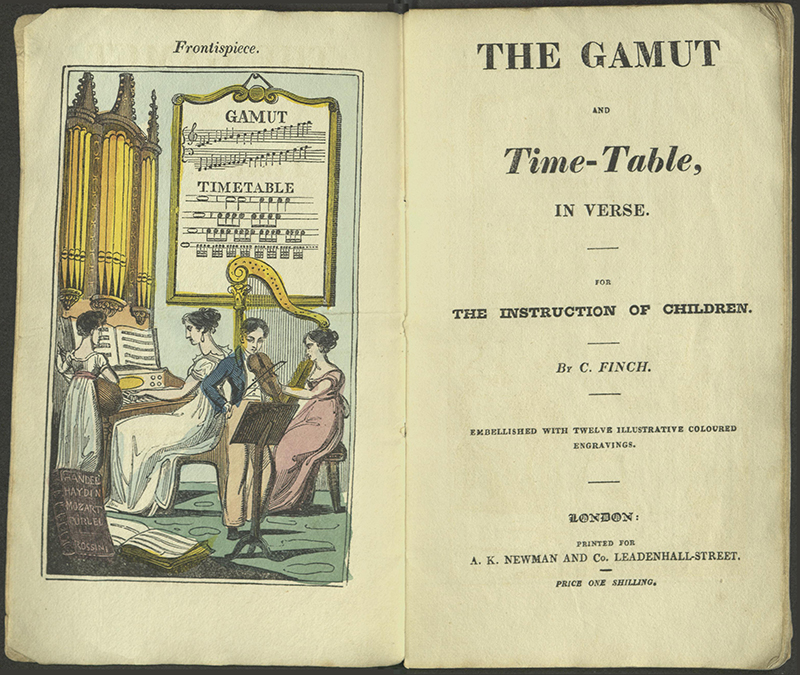

In spite of its rudimentary information, The Gamut was a very successful book. It was first printed in the early 1820s by Dean & Munday and sold throughout the decade under their name and also with A.K. Newman named as the publisher. Much of the attraction of the work must have been the appeal to gentility; the booksellers were peddling not just music education, but also social aspiration. Well-educated upper-class children, and especially girls, played and sang, providing music for impromptu and informal dancing, and as entertainment in private households. The Gamut conveys the expectation of fitting into a society of well-bred individuals not just through its ostensible topic, but also through a series of class markers that would have been understood by the contemporary reader.

In spite of its rudimentary information, The Gamut was a very successful book. It was first printed in the early 1820s by Dean & Munday and sold throughout the decade under their name and also with A.K. Newman named as the publisher. Much of the attraction of the work must have been the appeal to gentility; the booksellers were peddling not just music education, but also social aspiration. Well-educated upper-class children, and especially girls, played and sang, providing music for impromptu and informal dancing, and as entertainment in private households. The Gamut conveys the expectation of fitting into a society of well-bred individuals not just through its ostensible topic, but also through a series of class markers that would have been understood by the contemporary reader.

The Gamut is illustrated extensively with wood engravings – in spite of their name, a type of relief prints that can be set in the press at the same time as the type and printed simultaneously. The music as well was printed in relief, rather than from engraved copper plates; each note and its lines are a single piece of type and they are lined up to create a (slightly wobbly) staff. The illustrations have been colored by hand. These features hint at the prospective audience: the book is meant to be attractive, but not expensive. At one shilling it was well within the reach of a family of moderate means, including those of respectable merchants and tradesmen who were doing well. It might also have been bought by a more elevated clientele, to which group the lesser aligned itself by purchase.

The Gamut is illustrated extensively with wood engravings – in spite of their name, a type of relief prints that can be set in the press at the same time as the type and printed simultaneously. The music as well was printed in relief, rather than from engraved copper plates; each note and its lines are a single piece of type and they are lined up to create a (slightly wobbly) staff. The illustrations have been colored by hand. These features hint at the prospective audience: the book is meant to be attractive, but not expensive. At one shilling it was well within the reach of a family of moderate means, including those of respectable merchants and tradesmen who were doing well. It might also have been bought by a more elevated clientele, to which group the lesser aligned itself by purchase.

The illustrator stakes the book’s claim to participation in canonical musical culture in the frontispiece, with the names of Haydn, Mozart, Handel, Purcell, and the immensely popular Rossini, on the book cover in the foreground. The group of players – possibly a family – arrange themselves casually as if they were playing for their own amusement. They present an ideal picture of the pleasures of music for accomplished amateurs, although the large organ and harp both belong only in very affluent establishments.

Most of the instruments depicted were available in the homes of the merely well to do. There is a grand piano (or an out of fashion harpsichord), a small organ, a mandolin, two harps, and a succession of square pianofortes through the book. The appearance of the word “SMART” on the pianoforte on page 30 establishes a terminus post quem for the undated book. Henry Smart was a successful violinist, composer, and orchestra and oratorio leader who opened a piano factory in 1821 and his name evokes the fashionable music scene of London.

Most of the instruments depicted were available in the homes of the merely well to do. There is a grand piano (or an out of fashion harpsichord), a small organ, a mandolin, two harps, and a succession of square pianofortes through the book. The appearance of the word “SMART” on the pianoforte on page 30 establishes a terminus post quem for the undated book. Henry Smart was a successful violinist, composer, and orchestra and oratorio leader who opened a piano factory in 1821 and his name evokes the fashionable music scene of London.

The sisters are well-dressed and graceful – laudable examples of female accomplishment and behavior. Although the interiors are reduced to their essentials and set within curtains as if they were stage sets, the simplified paneled walls, patterned rugs, fashionable furniture, paintings of land- and seascapes, and a glimpse of a garden through the window convey comfort and prosperity.

The sisters are well-dressed and graceful – laudable examples of female accomplishment and behavior. Although the interiors are reduced to their essentials and set within curtains as if they were stage sets, the simplified paneled walls, patterned rugs, fashionable furniture, paintings of land- and seascapes, and a glimpse of a garden through the window convey comfort and prosperity.

The book’s final claim to gentility – identifying the author as C. Finch – is subtle and almost certainly fraudulent. There is no more complete contemporary attribution on record, but from the mid-century it was understood to refer to Lady Charlotte Finch (1725-1813), daughter of one earl and daughter-in-law of another, who served as royal governess to the fifteen children of King George III and Queen Charlotte. Although Finch retired in 1793, she was for three decades the most famous, and most noble, educator in England, and an early adopter of progressive educational theories and techniques. There is no reason to think she wrote the substandard verse which first appeared a decade after her death, and the publisher carefully did not say it was her work, but one suspects the implication was an additional attraction to purchase.

The book’s final claim to gentility – identifying the author as C. Finch – is subtle and almost certainly fraudulent. There is no more complete contemporary attribution on record, but from the mid-century it was understood to refer to Lady Charlotte Finch (1725-1813), daughter of one earl and daughter-in-law of another, who served as royal governess to the fifteen children of King George III and Queen Charlotte. Although Finch retired in 1793, she was for three decades the most famous, and most noble, educator in England, and an early adopter of progressive educational theories and techniques. There is no reason to think she wrote the substandard verse which first appeared a decade after her death, and the publisher carefully did not say it was her work, but one suspects the implication was an additional attraction to purchase.

The audience for The Gamut was respectable and financially comfortable, but the book conveyed a whispered promise of something better – a nicer house, more fashionable company, an accomplished family. I doubt anyone ever learned to play by reading and memorizing the book, but it must surely have provided an inducement to persist through the tedium of scales and dozens of repetitions of country dance tunes or the latest quadrilles.

The audience for The Gamut was respectable and financially comfortable, but the book conveyed a whispered promise of something better – a nicer house, more fashionable company, an accomplished family. I doubt anyone ever learned to play by reading and memorizing the book, but it must surely have provided an inducement to persist through the tedium of scales and dozens of repetitions of country dance tunes or the latest quadrilles.

Finch, Charlotte. The Gamut and Time-Table in Verse: For the Instruction of Children. London: A.K. Newman and Co., 1823.

Our copy of The Gamut can be read on the Internet Archive.

With the continuing closure of the Library, we are blogging regularly about books from the exhibition, The Girl’s Own Book. The exhibition’s run has been extended through the 2020-2021 academic year; information about when it will open and related programming will be available when we are able to give it. Please follow us on Facebook or subscribe here for notices of new blog posts.