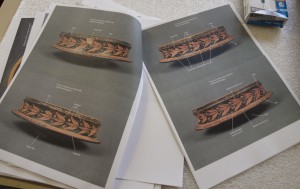

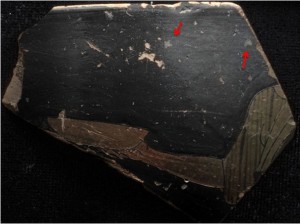

The Special Collections of Bryn Mawr College holds an extensive collection of Greek pottery, both decorated and undecorated. This summer I, a PhD student at Bryn Mawr College, was granted one of the NEH internships to study vases with painted and incised inscriptions. As some of them are difficult to identify even when working closely with the objects, I , with the assistance of the Special Collections Intern, Katy Holladay, who is interested in archaeology and has a strong interest in technology, sought a way to properly document inscriptions that can be difficult to see in photographs, or even when handling/studying artifacts. Alex Brey, another graduate student at Bryn Mawr College, suggested the use of Reflectance Transformation Imaging, or RTI, which he had previously utilized on some of the coins and graciously agreed to show us the process. RTI is a technique that uses sequential photography of an object with variant locations for the light source, which are then combined using a program to produce a manipulative image. The manipulative image allows for the exploration of the surface of the image with gradient lighting, unlike traditional museum-quality images such as seen below.

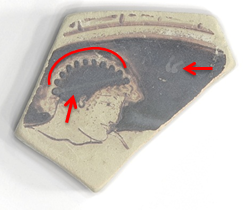

P.961, Traditional photograph that does not show the partial inscription in the image (KA)

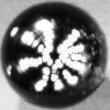

P.961, RTI Viewer with Normal Unsharp Masking Rendering Mode

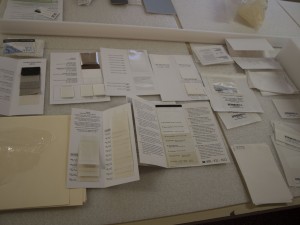

The equipment was easy to access, since only a few other objects are needed to capture the images for RTI:

- a camera and tripod

- an external flash (with a very long cord)

- a remote for the camera

- a pair of black spheres; they need to be included in the image in order to show the position of the light source to the program in each photograph

- a color card needs to be included in the first image.

The software to find and view the RTI images is provided by Cultural Heritage Imaging, free of charge: http://culturalheritageimaging.org/Technologies/RTI/

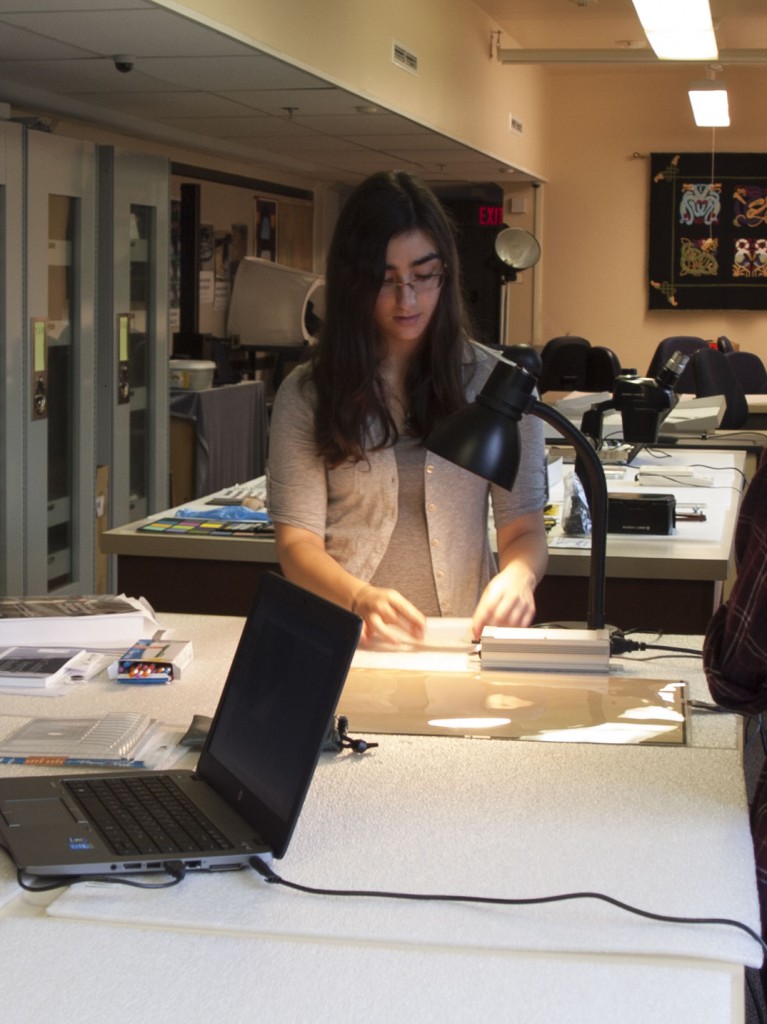

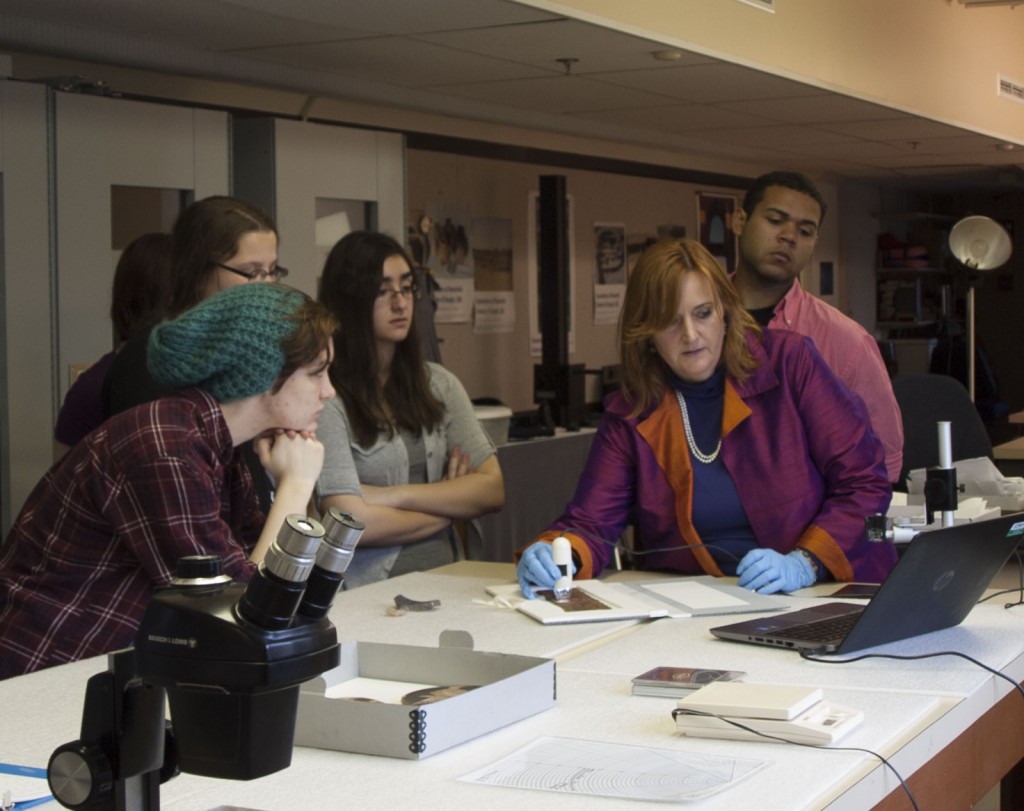

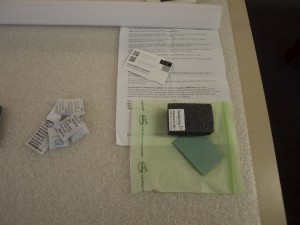

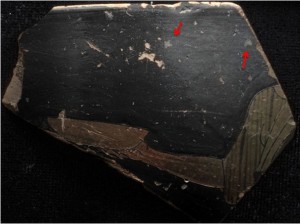

We began with flatter objects, small sherds that were more similar to the coins Alex had previously done and that did not have curved surfaces, which required more practice with the lighting. It turns out that the process was relatively easy: the camera and objects remain stationary with a sphere on either side. For standing objects, the spheres are raised up, such as on pencils in the photograph below; for flat objects laying down, the spheres can be resting. The spheres should be around 250 pixels in the final photos, so the sphere size will vary with the object and zoom. The flash is moved into different positions over and around the object in a dome while the object and the camera remain unmoved; others doing RTI have created actual dome structures as guides, but that was not necessary for our initial goals.

One person can do the process alone, but a second person is very helpful. We took between 50 and 120 pictures per object, depending on the size. Katy and I did run into some problems as we began the process, including the spheres originally being too small to accurately show the location of the light source in each image for the program. After becoming more familiar with the process, we captured images of complete vases; their size and the curving surfaces presented challenges as these objects reflect he light differently. At this point, we needed to be creative for mounting the spheres – eventually using the ball bearings, magnets, and foam to create mounts for the spheres with the assistance of Marianne Weldon, the Collections Manager of the Art and Artifact Collections, but originally using pencils as stands.

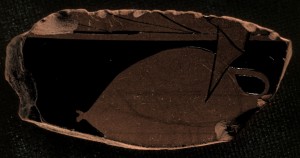

Danielle Smotherman and Katy Holladay taking RTI photography of L.P.8

A composite image of the light source for L.P.8

The RTI Builder program cannot handle spaces in any file names. It requires specific formats for the files, which initially caused us a few problems as well. We imported the raw files as .jpg and .dng into specifically-named folders from Adobe Bridge, although another similar type of program can be used, and then followed the process in the RTI software; this was rather user-friendly. The RTI Viewer has nine different rendering modes to examine the object, once the file is compiled. The viewer also allows the user to zoom in on the images, which is why we took the images at higher resolutions, and to take snapshots of the image on the screen, such as the examples seen below.

P.95, Bryn Mawr Painter, RTI Viewer with Default Rendering showing the full inscription

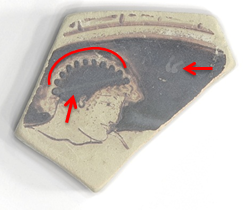

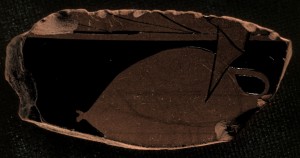

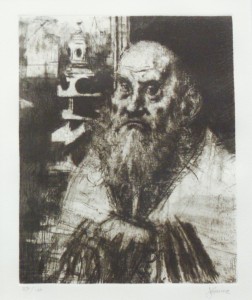

Using the RTI Viewer, various rendering modes can be used to explore the surface of the object, including raking light at various angles. Details can be highlighted, for instance the full inscription on P.95 can be read in the snapshot from the RTI Viewer seen above. The same snapshot also shows the contour lines evident around the reclining figure, his cup, and the hanging pipes case. The RTI provided much more than just a clearer look at the inscriptions on these vases: it indicated better evidence of the preparation work of the paintings, including highlighting sketch marks and contour lines, as well as demonstrating the presence of other techniques, such as added clay along the head. Katy noted the presence of finger prints on the name-piece of the Bryn Mawr painter, seen in the still photograph captured from the RTI viewer, seen below. In the right image below, the faded details of a wreath that had been painted on top of the hair of the youth are clearly shown with the RTI, although they can be difficult to see in traditional photos. RTI also allowed us to capture the sketching of a kylix on P.985, which is very difficult to make out in traditional photographs.

P.95, Bryn Mawr Painter, RTI Viewer with Specular Enhancement Rendering Mode

P.212, Ancona Painter, RTI Viewer with Diffuse Gain Rendering Mode

P.985, unattributed, RTI Viewer with Diffuse Gain Rendering View

The files we created can provide better access to the objects for scholars unable to physically visit the collections and can be used as educational materials. Katy will be working with Rachel Appel, the Digital Collections Librarian, in hopes of finding a way of making the RTI images available via our online database, Triarte at http://triarte.brynmawr.edu. Also, Katy has made a short video that shows the actual RTI viewer, which can be seen at http://www.viddler.com/v/8aa9f1ac. In addition to web access, finding other platforms to present the RTI images with could be a fantastic addition to future exhibitions, inviting guests to interact with the objects as if moving them around in different lighting. Katy has produced a guide of our process for future use that goes into much more detail in the hopes that RTI will continue to be used in collections and possibly expanded to other forms of lighting, such as IR and UV, which only require the different light sources. Overall, our experiences suggest that this is a viable and valuable process for other objects and classes of materials in the collections. I would very much like to encourage others working with objects in the collections at Bryn Mawr to make use of RTI and perhaps other collections as well. RTI is relatively easy and inexpensive process that does not require highly specialized equipment and that can greatly enhance access to the objects.

Danielle Smotherman, Doctoral Candidate in Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology