By Cassidy Gruber Baruth

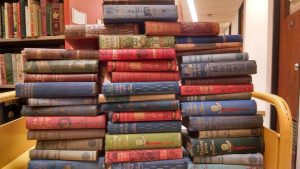

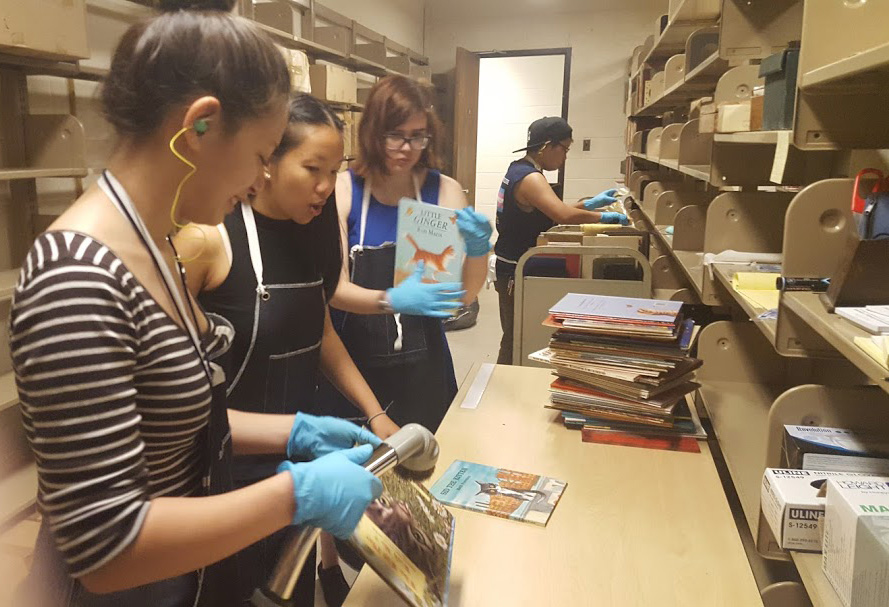

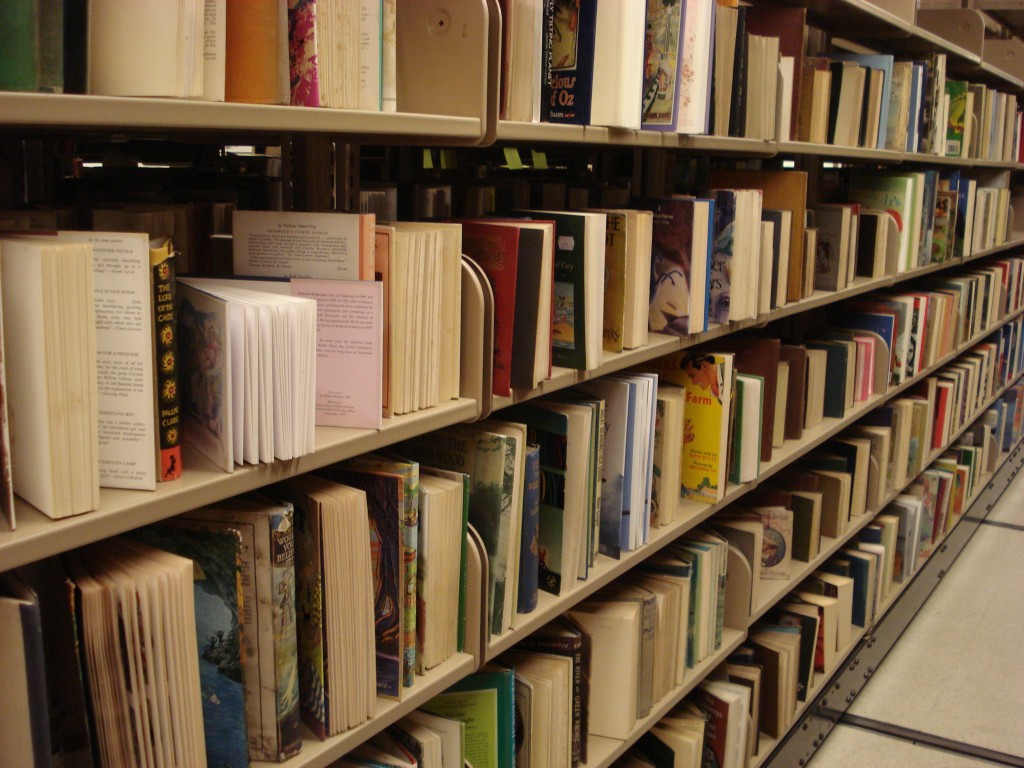

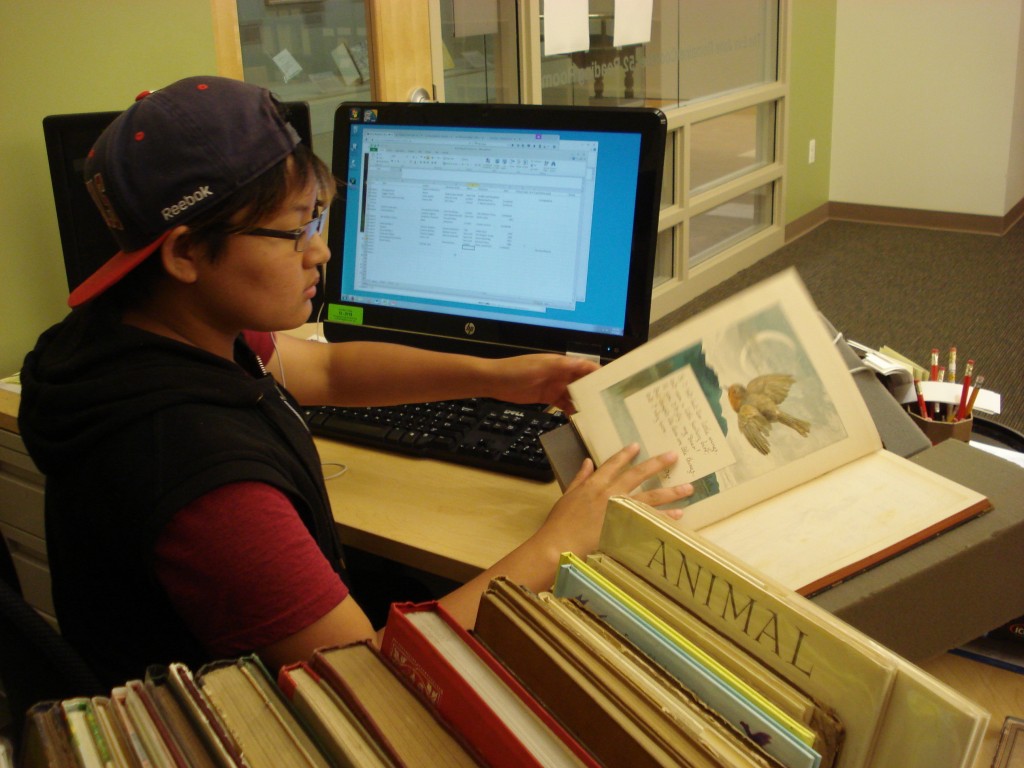

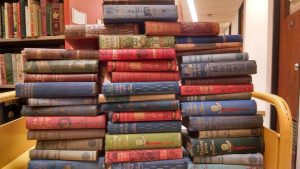

This summer, my coworkers and I unpacked over 630 boxes of primarily children’s books that were donated to Bryn Mawr by alum Ellery Yale Wood. I knew a few of the older authors–Lewis Carroll, Enid Blyton, and Louisa May Alcott–but the vast majority were unfamiliar. Dozens of authors, although prolific and beloved during their era, didn’t stand the test of time. Mrs. Molesworth was one such writer, a woman who wrote so extensively that we joked half of our ‘M’ section was comprised of her books. I became curious about her, an author who produced dozens of books over her lifetime and whom Edward Salmon, a critic for the periodical The Nineteenth Century, deemed “the best story-teller for children England has yet known,” but who is unknown today.

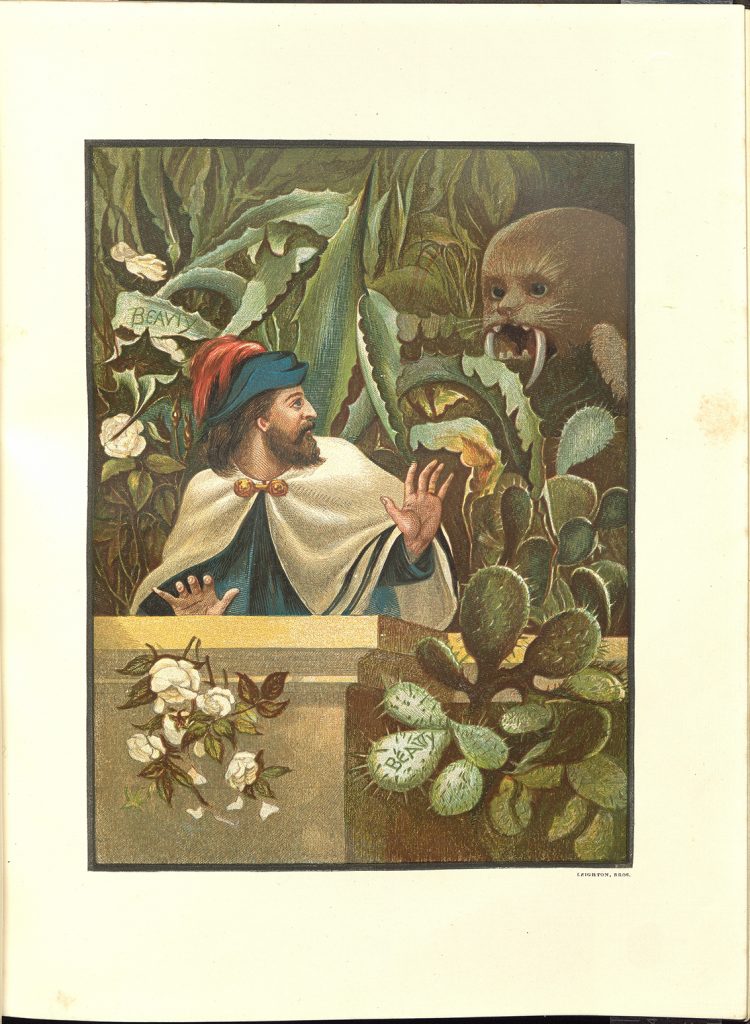

Mary Louisa Molesworth (nee Stewart) was born in Rotterdam in 1839. She moved from the Netherlands to England when she was still a child and lived in Manchester for the duration of her childhood. As a child, there were signs of the writer she would become. She devoured books and loved listening to the fairy stories of her grandmother. She began to repeat these fairy stories to other children, gradually inventing new tales. She enjoyed playing make-believe, but preferred shells over dolls, as they provided a blank, faceless canvas onto which she could project her stories.

She married Major R. Molesworth in 1861 and had four daughters. By 1869 she had begun writing a book when scarlet fever struck her family, killing her eldest daughter. The tragedy spurred her to finish and publish the book Lover and Husband, written under the pseudonym Ennis Graham. Her adult novels were given firmly lukewarm praise, acknowledging the grace and quality of her writing, but finding the final product lackluster. One critic called Lover and Husband, “written with good taste, naturally and simply; the conversations are easy, the characters, if not profoundly studied, are life-like…” Sir Noel Paton, a friend of Molesworth’s, thought her adult novels were written “indifferently,” but encouraged her to try writing children’s literature. Molesworth already had a supply of children’s stories at hand: she had continued the storytelling tradition of her grandmother, inventing new bedtime stories for her own children.

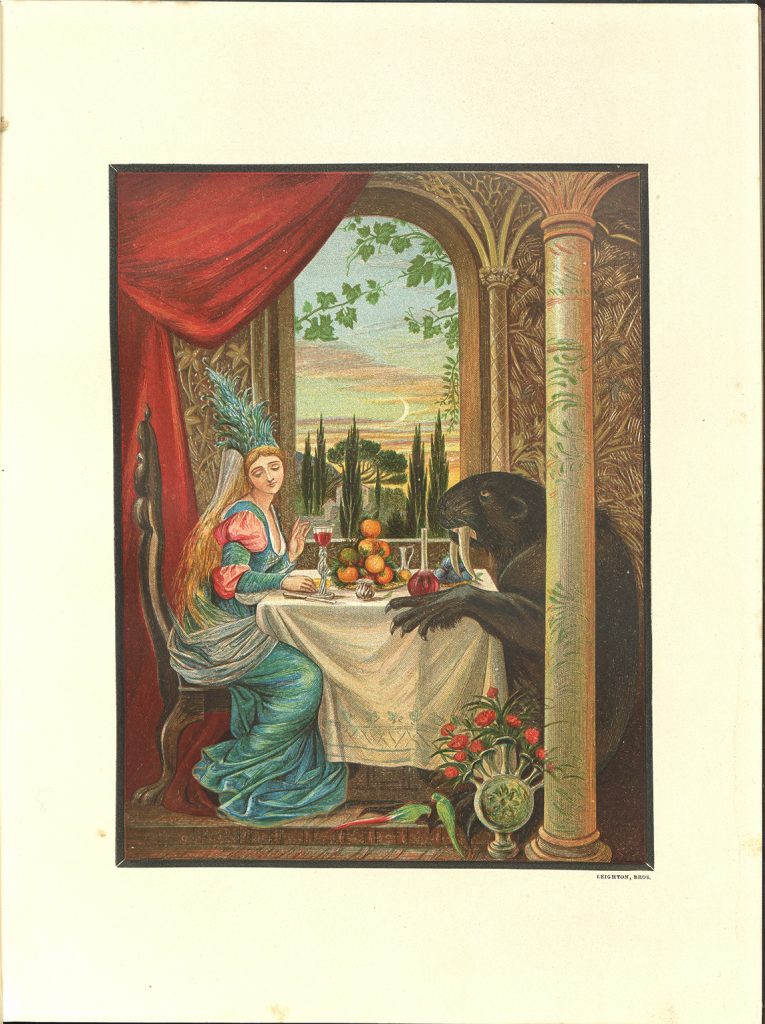

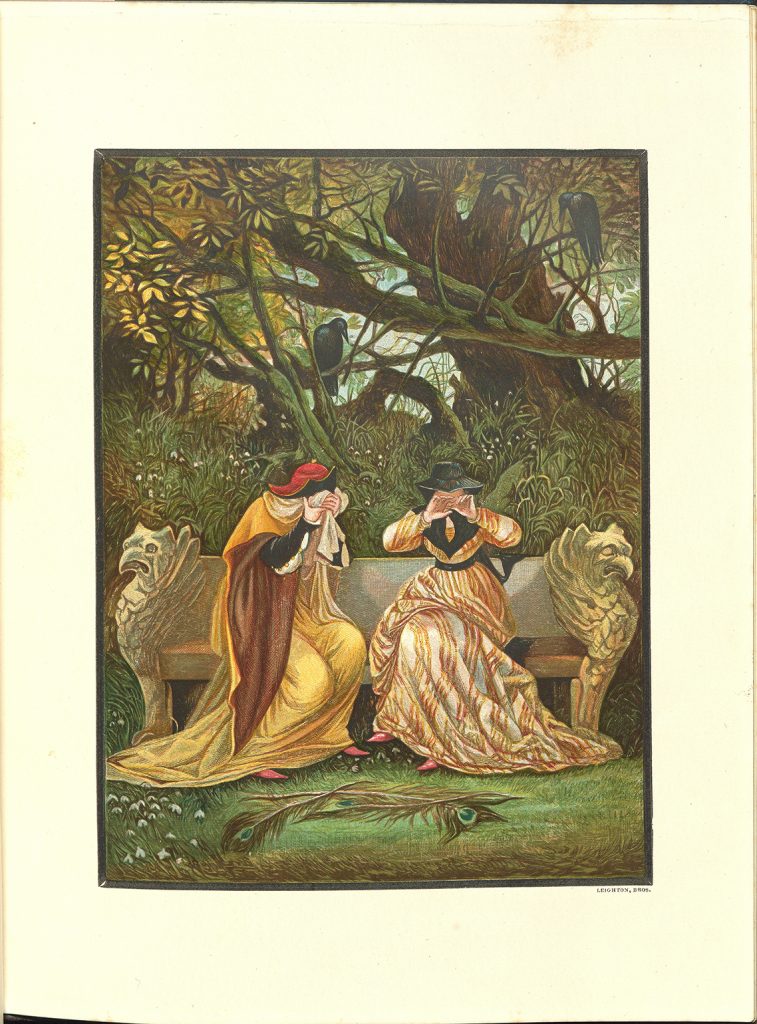

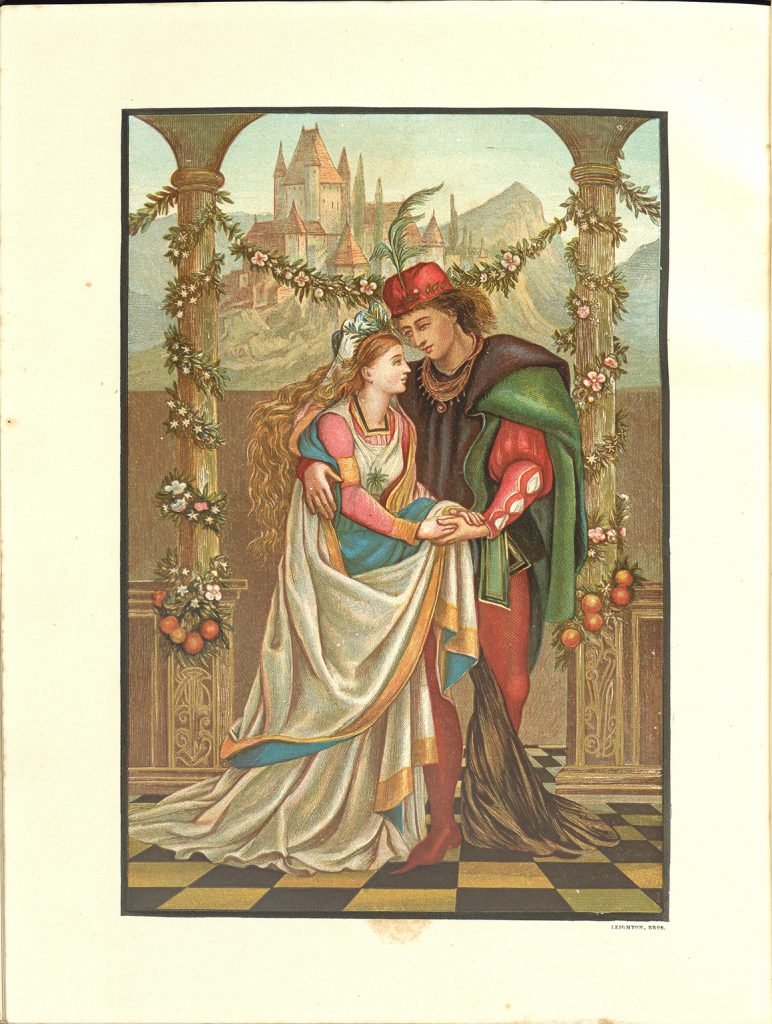

Her first children’s book, a collection of short stories entitled Tell Me a Story, was a resounding success, and a second book quickly followed, and then a third, and a fourth. The qualities which dragged her down as an adult novelist – her simple, easy-going manner of writing – proved valuable to her as a children’s author. Her characters and stories were simple enough for children to follow, but still fresh and engaging. Molesworth wrote with a joy that sprang through the page, using italics, exclamations, and colloquial speech to emote childish joy and delight. She often invented words or wrote in a slangy manner in order to imitate a child’s speech. As Jane Darcy expresses in ‘Works not Realized: The Work of Louisa Molesworth,’ Molesworth wasn’t interested in moralizing or lecturing, as previous authors of children’s fiction had been; rather, she wrote in a child-like voice about topics that children cared about. Her interest and compassion for children comes across, even to a 21st century reader. As I skimmed her novels, I was struck by the energy of her characters and the vibrancy of her prose. Some of what she wrote is indubitably quaint and outdated, but I was unexpectedly impressed by how approachable her stories remain.

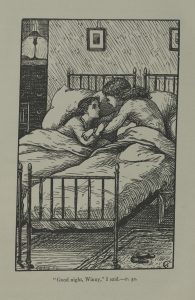

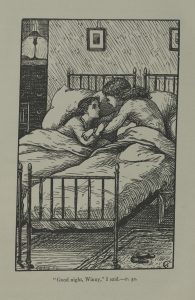

Molesworth was part of a new generation of children’s writers who wrote during the age of literary realism, a movement that moved away from romantic and idealized forms of literature and instead promoted more life-like characters and settings. She constantly drew on her own life experiences for inspiration, writing her children into stories such as ‘Goodnight, Winny’; featuring Holland in one of her most famous books, The Cuckoo Clock; and depicting aspects of her own childhood in the story ‘My Pink Pet.’

Molesworth’s stories dealt with children and growing up: their interests, trip-ups, relationships, and triumphs. Carrots, one of her most popular books, is the growing-up story of a little boy nicknamed Carrots and his older sister, Floss. The novel is a sweet vignette of growing up, making mistakes, and moving forward as Carrots accidentally steals a coin from his nurse and must learn to make amends. Another book, The Cuckoo Clock, similarly deals with themes of mistakes, forgiveness, and friendship after a young girl ruins her aunt’s cuckoo clock in a fit of anger, later discovering that the cuckoo inside is actually a magical creature who wants to be her friend. Although the children in Molesworth’s stories are far from perfect, the tone she takes is patient and understanding, not moralizing or condescending. It is understood that making mistakes is a natural part of growing up, and she gives them the freedom to explore and reflect.

Although Molesworth wrote for children, the quality of her writing and characters were recognized by some of the finest writers of the day. The poet Algernon Charles Swinburne commended Molesworth’s abilities, stating:

“It seems to me not at all easier to draw a life-like child than to draw a life-like man or woman. Shakespeare and Webster were the only two men of their age who could do it with perfect delicacy and success . . . . Our own age is more fortunate, on this single score at least, having a larger and far nobler proportion of women writers: among whom, since the death of George Eliot, there is none left whose touch is so exquisite and masterly, whose love is so thoroughly according to knowledge, whose bright and sweet invention is so fruitful, so truthful, or so delightful as Mrs. Molesworth’s.”

One of the greatest lessons I have learned from this job, and from Mrs. Molesworth especially, is that there is a story behind everything. It is a joy to unearth the person behind the title page, and discover their contributions, however big or small they may be. Mary Louisa Molesworth left behind over 100 novels and stories for both adults and children after her death in 1921. She has been largely forgotten, but her influence lives on. Her style inspired writers such as E. Nesbit, author of Five Children and It, and Frances Hodgson Burnett, author of The Secret Garden and A Little Princess. Due in no small part to Molesworth’s many stories, realistic fiction proved a wildly popular children’s genre and remains so to this day.

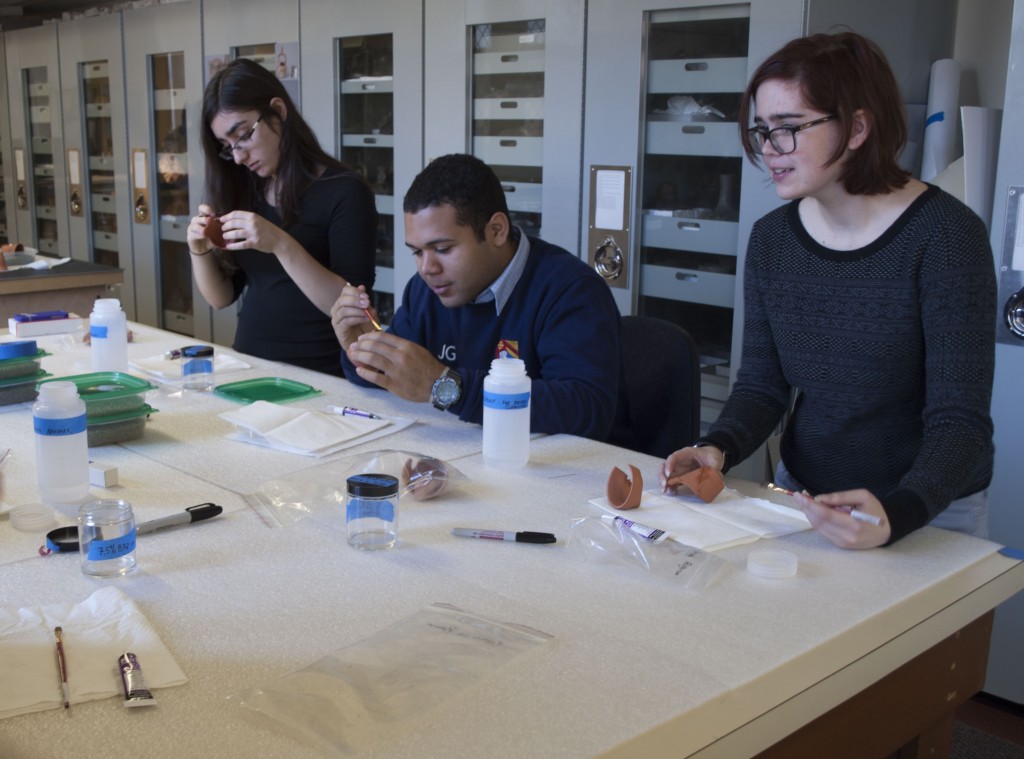

Cassidy Gruber Baruth (BMC 2019) has been working this summer in Special Collections. Among many other tasks, she has unpacked, cleaned, sorted and inventoried books from the Ellery Yale Wood Collection.