By Rebecca Kelly-Bowditch, Friends of the Library Intern, Summer, 2019.

Recently, a researcher at Northwestern University contacted Special Collections requesting all of our information regarding Marie Curie’s visit to Philadelphia and Bryn Mawr in the spring of 1921. This was something of a surprise, as no one here knew that the famous scientist had visited the college. Online, records abound of Curie’s time in Philadelphia; as do records of a speech M. Carey Thomas gave in New York to welcome her to America. Looking through our Archives, I was also able to find a substantial amount of correspondence from Thomas planning for Curie’s visit. However, if Curie had come to Bryn Mawr, why didn’t anyone know about it? I began reading Thomas’ letters to try to find out the story behind this visit.

Thomas had grand plans for Marie Curie’s visit, and was heavily involved in planning her time in Philadelphia. The two-time Nobel-winning French scientist exemplified to Thomas the ideal of the college woman: Curie’s education and determination enabled her to discover radium and earn international respect for her contributions to the understanding of radioactivity, despite her gender. To Thomas, Curie’s visit was the chance to both inspire American college women and to bolster her ongoing battle for women’s rights. Marie Curie, however, was not one to flaunt her fame. In fact, she had a deep distaste for the limelight and avoided public engagements whenever possible. She was of the opinion that science was for the betterment of society, not the betterment of an individual. She and her late husband, Pierre, had begun their work in a run-down shed in 1897; their aversion to fame and her refusal to patent the radium production process meant that by 1921, Curie’s lab was still inadequate and her supply of radium was dwindling. An American magazine editor and socialite, Mrs. William Brown Meloney, had learned of Curie’s struggles and contrived to raise the funds needed to continue her work; a single gram of radium cost over $100,000. Unfortunately for the reclusive scientist, Meloney’s plans centered on a very public appeal to the women of America. Using her magazine, The Delineator, as a platform, she stressed the significant impact which American women as a group could have on the future of science by each contributing small amounts of money to Curie’s research. To facilitate the fundraising, Meloney formed the Marie Curie Radium Fund, led by two Committees: one of well-known scientists (all men) and one of wealthy, philanthropic women.

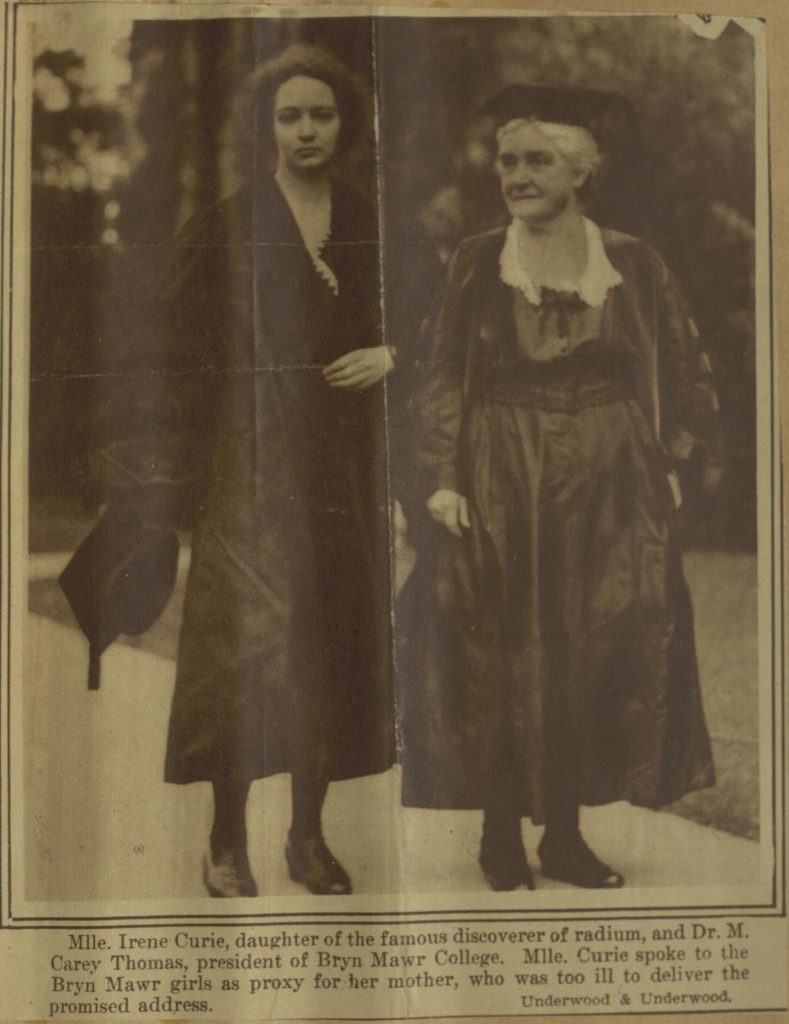

Mrs. Meloney was as extroverted as Marie Curie was introverted. Despite their opposite personalities, the two became close friends and Meloney convinced Curie to travel to America to support the fundraising being done in her name. Curie would spend seven weeks in May and June traveling the country and receiving honors, culminating in the presentation of a gram of radium by President Harding. The Radium Fund Committee was responsible for planning Curie’s itinerary, and one of the major events was to be a grand assembly at Carnegie Hall, where Curie would “be welcomed by the university women of the United States.” M. Carey Thomas and other notable women were to give speeches. Meloney accompanied the scientist throughout the trip, along with Curie’s daughters, Irene (23) and Eve (16). Irene was by now working as her mother’s lab assistant; she would later go on to win her own Nobel Prize.

While the Radium Fund was based in New York, local branches were formed in other cities. M. Carey Thomas was chosen to organize the Philadelphia Committee, serving both as Treasurer and Chairman. Thomas embraced her role with enthusiasm and recruited influential Philadelphians as Committee members, including two women doctors. In the months leading up to Curie’s visit, much of Thomas’ time was spent soliciting donations and corresponding about fundraising efforts. In addition to requesting donations from wealthy Philadelphians, Thomas asked all Bryn Mawr students to donate $1. Despite initial concerns about the Philadelphia Committee’s ability to reach their goal of $5000, they ended up contributing a total of $7489.74.

While the Radium Fund was based in New York, local branches were formed in other cities. M. Carey Thomas was chosen to organize the Philadelphia Committee, serving both as Treasurer and Chairman. Thomas embraced her role with enthusiasm and recruited influential Philadelphians as Committee members, including two women doctors. In the months leading up to Curie’s visit, much of Thomas’ time was spent soliciting donations and corresponding about fundraising efforts. In addition to requesting donations from wealthy Philadelphians, Thomas asked all Bryn Mawr students to donate $1. Despite initial concerns about the Philadelphia Committee’s ability to reach their goal of $5000, they ended up contributing a total of $7489.74.

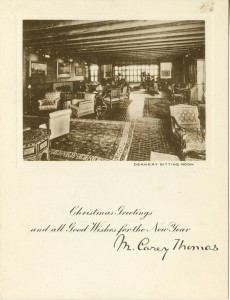

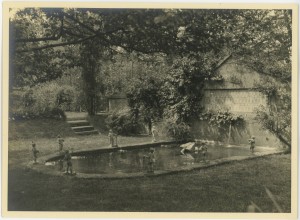

In addition to fundraising, Thomas took charge of planning Curie’s itinerary for Philadelphia. Frequently corresponding with Meloney and with other members of the Philadelphia Committee, she arranged for Curie, her daughters, and Meloney to stay with her at the Deanery for May 23rd and 24th. She planned a full schedule for the scientist, with many opportunities for Curie to appreciate Bryn Mawr. On the 23rd, the group would arrive and have lunch in Philadelphia before touring the Women’s Medical College of Philadelphia where Curie was to be awarded an honorary degree, followed by another honorary degree conferral at the University of Pennsylvania, dinner at Bryn Mawr, and finally a ceremony at the College of Physicians. Curie would spend the night at the Deanery, then visit several radium laboratories the next morning. Thomas planned a large garden party to be held in the Deanery garden that afternoon, and that night the American Philosophical Society would also honor Madame Curie.

Unfortunately for Thomas, plans quickly began to fall through once Curie arrived in America. On May 12th, Thomas wrote to Meloney to confirm cancellation of the radium laboratory trips, noting her disappointment that luncheon at Bryn Mawr had also been cancelled. The garden party was still scheduled as planned, but Thomas hoped to secure more of the scientist’s time. She entreated Meloney to convince Curie to substitute a “brief lecture, or half a brief lecture, in French” for Bryn Mawr students, and asked her to explain to Curie that the only reason why the college was not conferring upon her an honorary degree was because the founders had not granted that power. A couple days later, Thomas wrote to her Vice-Chairman, Dr. John G. Clark, to explain the reason behind the cancellations: Curie had decided to secretly visit the Welsbach plant in New Jersey, which produced mesothorium (an isotope of radium).

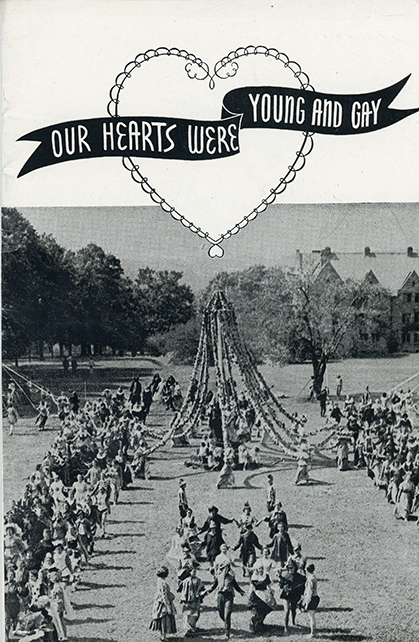

May 19th brought more bad news. Thomas wrote Dr. Martha Tracy of the Women’s Medical College to inform her of changes to the itinerary. Curie’s heart had failed, and “she had on Tuesday night two very serious heart attacks.” As a result, all functions were to be cancelled or minimized as much as possible. Curie would arrive at ceremonies just in time to receive the honorary degrees or awards, then leave immediately. Her daughters would attend the full ceremonies and other events in her stead. Curie managed to attend some of the award ceremonies and did indeed visit the Welsbach plant, where she was presented with 50 milligrams of mesothorium, but she arrived late to Philadelphia and her daughters stood in for her on many occasions. Thomas was forced to concede most of her grand plans for Curie’s visit, but the much-anticipated garden party still took place. According to the Bryn Mawr College News of June 1st, 1921 there were 700 guests in attendance, but Curie was too ill to receive or speak and was forced to leave the party early. Her daughter and lab assistant Irene stepped in on the same day to present a lecture to Bryn Mawr students about her mother’s work and discoveries.

Although Thomas and Curie did not end up interacting as much as the former had hoped, they did correspond occasionally after the trip. Thomas sent Curie some newspaper cuttings which she thought she would be interested in, and there is a record of Thomas receiving a card and picture from Curie addressed to the students of Bryn Mawr. Thomas and Meloney continued to write as well, and in 1929 Meloney wrote telling Thomas of a recent discussion with Curie in which the scientist had spoken of her fond memories of meeting Thomas.