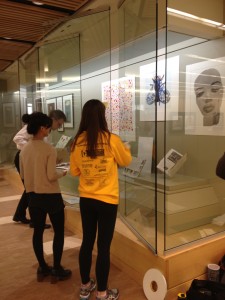

The Spring 2013 course “The Curator in the Museum” at Bryn Mawr College mixes theory into practice in the new exhibition “Making our World” located on the second floor of Canaday Library. Through readings and guest lectures related to the broader course theme of analyzing the “institution” of the museum and all its related parts, we integrated these models into our own project exhibition and corresponding education program for local high school students.

The Spring 2013 course “The Curator in the Museum” at Bryn Mawr College mixes theory into practice in the new exhibition “Making our World” located on the second floor of Canaday Library. Through readings and guest lectures related to the broader course theme of analyzing the “institution” of the museum and all its related parts, we integrated these models into our own project exhibition and corresponding education program for local high school students.

The following updates — written and edited by students as part of the team-based approach to the entire project — are reports on our progress along the way. Please let us know your thoughts.

Decision-making and “Making Our World”

Student blogger: Christine Villanueva

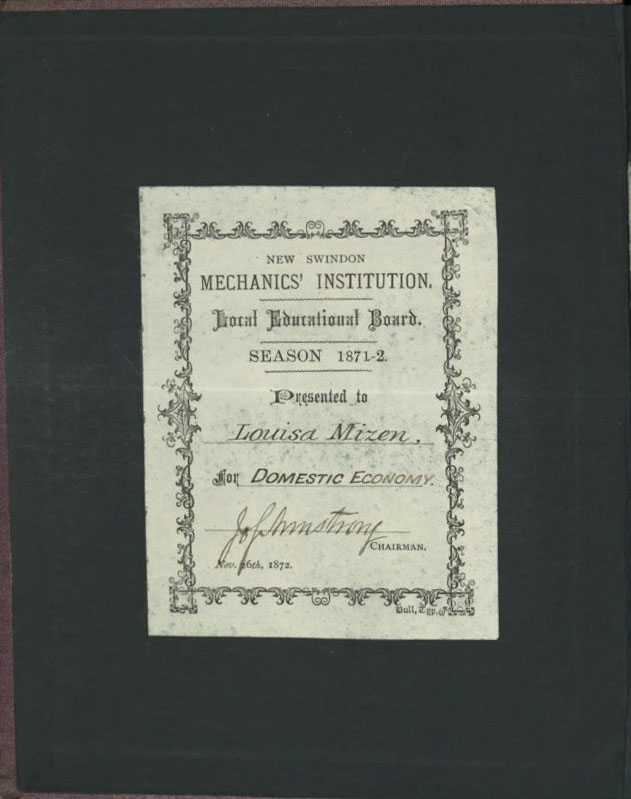

Curator Jennifer Redmond, Director, The Albert M. Greenfield Digital Center for the History of Women’s Education, introduces students to the Taking Her Place exhibition on the first day of the semester.

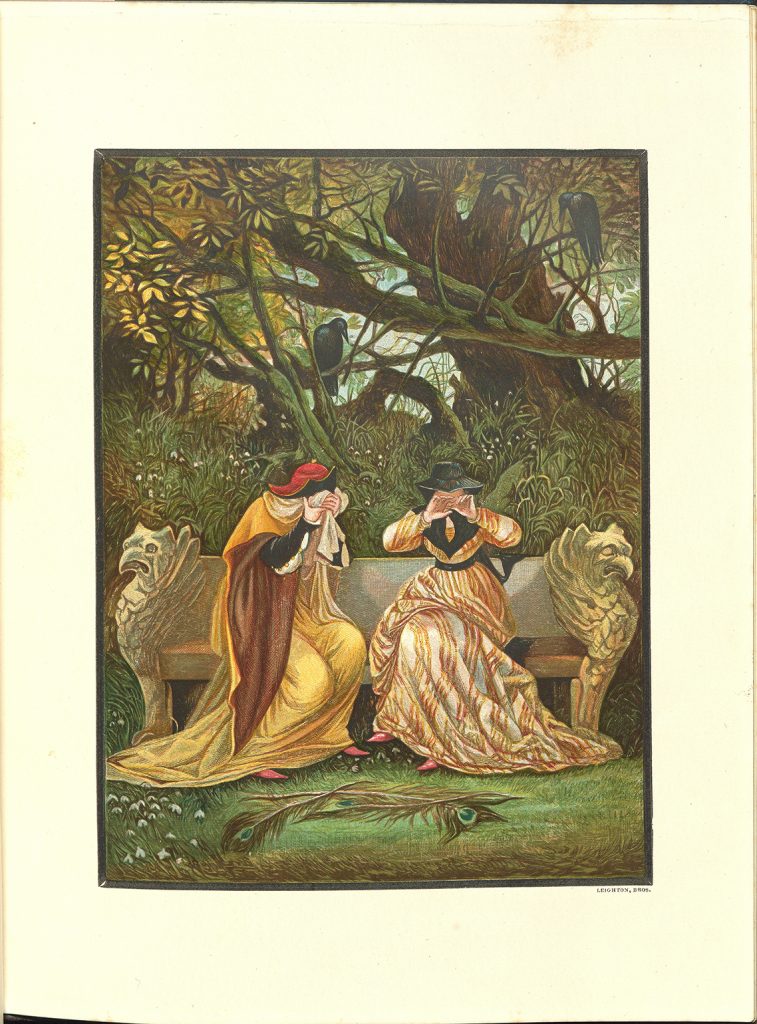

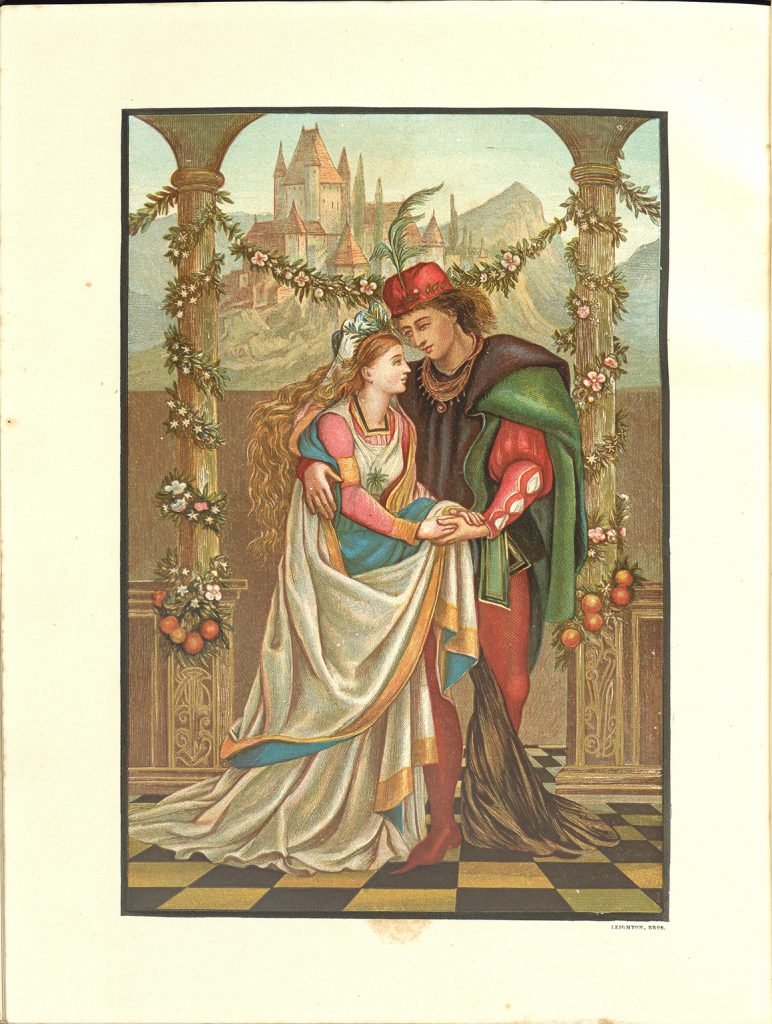

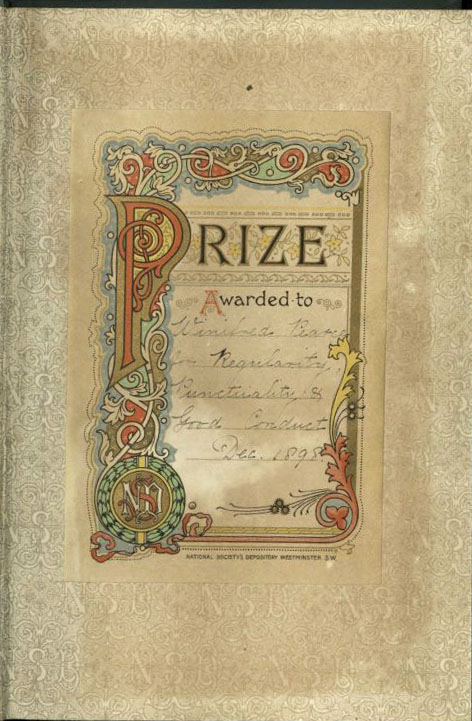

Making Our World is a satellite exhibit centered on main exhibition Taking Her Place located in Canaday’s Rare Book Room. As a departure from Taking Her Place (an exhibition dedicated in exploring the early history of women’s higher education and Bryn Mawr College’s parallel role in providing women of the 19th/early-20th centuries public access beyond the domestic sphere), Making Our World focuses on four contemporary Bryn Mawr alumnae. Since the post-war period, Bryn Mawr has remained an environment that fosters the same intense intellectual curiosity that it did for women in the 19th/early 20th centuries, giving them public access to contribute more actively to the world around them.

The collected cultural ephemera that included (among other things) a computer, yearbooks, magazines, pamphlets, photographs, and artworks were donated by each of the four Bryn Mawr alumnae profiled. Each was generous with her time and participation with the project, but discretion as a value revealed itself of tantamount importance as research in developing the story and thematic elements of Making Our World. The alumnae profiled in Making Our World –Courtney Pinkerton, Kimberly Blessing, Margery Lee, and Jacqueline Levine –not only served as subjects in order to explore how experiences at Bryn Mawr shaped their lives, but also as women to celebrate. In that light, the exhibitions group sought to find objects that best represented and respected the women and their stories, and also how each have impacted Bryn Mawr’s community.

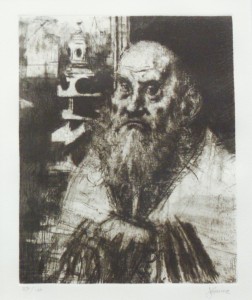

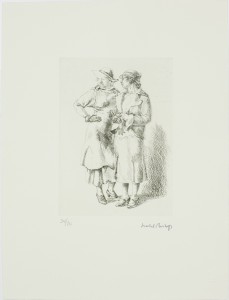

In the case of Margery Lee, Class of 1951, instead of focusing on her experiences as an undergraduate at Bryn Mawr College and her professional career, Lee insisted on focusing on the collection of artworks she donated to Bryn Mawr College and her numerous experiences in the art world. It was clear that her love of art she shared with her husband had been a vital and defining experience in her life. We respected her insistence on this significant aspect of her life by having her collection of artworks take center stage as indicative of Lee’s experiences and accomplishments from Bryn Mawr. She has donated over a dozen artworks to the college, and selecting which works to highlight from the impressive pool of candidates proved a fun task for the exhibitions group as executive “curators” of Making Our World. The objects group pulled several pieces for us to consider. These included a large-scale photograph by local and contemporary artist David Graham, a photograph by prolific and controversial artist Andres Serrano, a screen print by Warren Rohrer, and lithographs by Jim Dine and Jody Pinto.

Working out the installation details

Initially unsatisfied by the pool of works pulled by the objects group, we used triarte.brynmawr.edu, the arts and artifacts database of Bryn Mawr and Haverford colleges to see what other works could be considered for the exhibit. We rejected the Jim Dine lithograph because we felt its heart motif too sentimental, obvious and ‘on the nose’ for the exhibit’s theme and title. We loved that Bryn Mawr owned an Andrew Serrano photograph of a close-up girl’s pierced ear and earring titled “Child Abuse II”, but felt the content of the photograph incongruous with our exhibit, and felt that Serrano’s piece could be better served in a future exhibit. Its inclusion in Making Our World felt forced to us given Serrano’s critical intent for the work. Rohrer’s screen print “Barks and Marks”, David Graham’s photograph of a William Penn impersonator “Bud Burkhart as William Penn, Three Arches, Levittown, PA”, and Jody Pinto’s landscape lithograph “Fingerspan for Climbers Rock Fairmount Park” were all seriously considered to display for the exhibit.

To be frank, however, we wondered if there were other works in Lee’s collection that held the same “big-name” artist recognition as Andres Serrano. Though our anticipated audience was not geared towards a distinctly informed art audience familiar with an artist like Serrano, we felt that, in part, by focusing on Margery Lee’s donated works as indicative of Bryn Mawr’s first-rate Art and Artifacts Collections, we wanted to display works that could carry broad-based appeal and familiarity, and excite an audience approaching not only Making Our World, but Bryn Mawr College itself. Although Rohrer, Graham, and Pinto’s works are of great quality and content (representative of Lee’s strong local connection to the Pennsylvania art scene), we were confident that Lee’s collection was deep enough to pull other works representative of Bryn Mawr’s world class art collection.

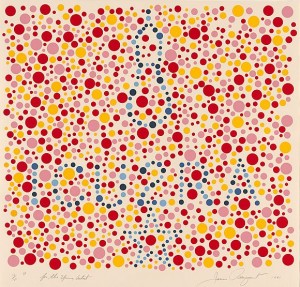

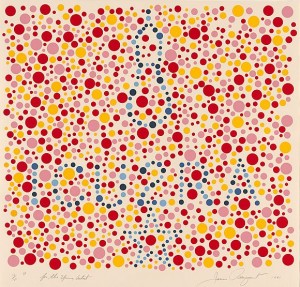

As such, we were excited to discover Lee had also donated George Segal and James Rosenquist serigraphs and an Ansel Adams photograph to the college. We wanted to include the Ansel Adams photograph “Dead Tree, Sunset Crater National Monument, Arizona” but were informed that it had already been exhibited in a prior show, Double Take, a year ago. Because of the photographic medium and the work’s age, conservation rules dictate that photographs only be displayed (under strict lighting guidelines) every few years. In order to preserve Adams’s work for future Mawrtyrs, we were unable to display it for this exhibit. However, the James Rosenquist serigraph “For the Young Artist”, an imitation of a color perception test called an Ishihara Color Test that spells out “ICU2RA*” (roughly “I see you too are a star), proved to be the fulcrum around which we based Margery Lee’s display. It was colorful and dynamic, it was by renowned Pop artist James Rosenquist (whose works are in the collection of MoMA and the Met, among others), and most importantly, its thematic content of mentorship between young and old generations proved a home run. As the only abstract, non-figurative artwork displayed, we chose the Rosenquist piece over Rohrer’s “Barks and Marks”.

For the Young Artist, James Rosenquist

Serigraph on wove paper

2007.12.3

However, its size proved to be slightly detrimental and highly difficult within our display case. But, the exhibitions group pushed for its inclusion as it also worked well loosely juxtaposed next to alumna Kimberly Blessing’s technology oriented objects. We were happy with the other artworks the objects grouped pulled –Marlene Dumas’s “Supermodel”, John Kindness’s “China Cabinet Fly”, and David Graham’s William Penn photo –but their respective sizes proved too large for the space, and we found ourselves needing to cut one piece. Dumas’s “Supermodel” was a shoe-in; it is the only work by a female artist, and, we felt, played well against other featured alumna and art collector Jacqueline Levine’s displayed artworks of figuratively focused, and politically/racially charged (in different degrees) works. Ultimately, we chose etching “China Cabinet Fly” against Graham’s photograph because it paired better between the Rosenquist and Dumas prints.

Upon reflection, perhaps it would have proved better to mix up the displayed artworks, exhibiting the large-scale William Penn photograph instead in order to challenge audience expectations. But, as exhibition designers, we stand strongly behind our decisions to display other works against others, as all decisions were reached thoughtfully and collaboratively. We feel that the final three artworks exhibited for Margery Lee cohesively celebrate both her and the college’s art collection, and more broadly, the community oriented engaged learning of Making Our World.