Thanks to the work of our web services team, you can now subscribe by e-mail or RSS for musings, news, and updates from Bryn Mawr College Special Collections. Hit the link at the top of the page (just below the image), and never miss a post.

Category Archives: Friends of the Library

Remembering Jane Martin

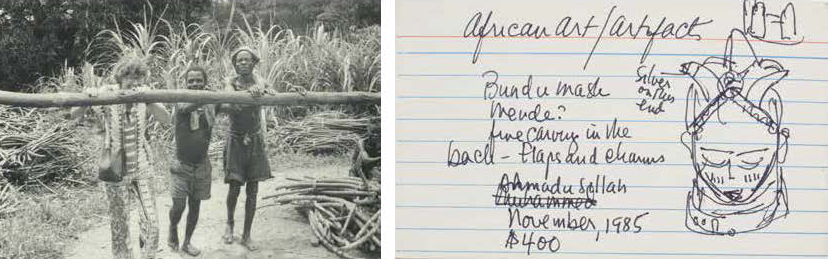

Photograph of Jane Martin and workers at Nyema Smith’s sugar cane production in Liberia (April 15, 1976); Catalog Card written by Jane Martin (c. 2000) from The Jane Martin Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives

Special Collections remembers Dr. Jane Martin (Class of 1953, MA 1958), the generous donor of a significant collection of African Art and related papers from her professional work in Liberia, who died on April 14. After graduating from Bryn Mawr with two degrees, Martin went on to earn her PhD in African History from Boston University in 1968. Her research focused on the Glebo of Eastern Liberia, and many of her interests there are reflected in the archives she donated to the College, including material on specific individuals in the Kru tribe, African women and their roles in education and society, and governmental and non-profit organizations in Africa.

Martin lived and worked in West Africa for several years, teaching African History at the University of Calabar in Nigeria and the University of Liberia in the 1970s. Her papers demonstrate her careful thinking about how to teach history and what to teach, as well as research interviews she conducted during this time. From 1984 to 1989, she was Executive Director of the United States Educational and Cultural Foundation in Liberia, administering the Fulbright Program and other cultural exchange programs. She was a strong advocate for binationalism between the US and Liberia for all of her life, continuing this work at the African-American Institute in New York, when civil war forced Martin to leave Liberia in 1989.

Throughout her travels in Africa, Martin collected a wide variety of art and cultural objects, some 150 of which she donated to the Art & Artifacts Collection at Bryn Mawr. These include helmet masks danced by women of Liberia’s Sande society, Ashanti gold weights, baby carriers, toys made by the artist Saarenald T. S. Yaawaisan from recycled flip-flop sandals, and a Baule Chief’s chair. She documented her collecting with various field notes, photographs, and correspondences, all of which serve to enrich the gift of objects immeasurably.

Works from Martin’s Collection have been featured in exhibitions organized by students since their arrival at the College in 2016, including On Selecting: Profiles of Alumnae Donors to the African Art & Artifacts Collection (Spring 2017) and Mirrors & Masks: Reflections and Constructions of the Self (Spring 2017). These materials are regularly used in courses across a variety of fields at the College.

To learn more, visit:

Naughtiness and – Disproportionate? – Punishment

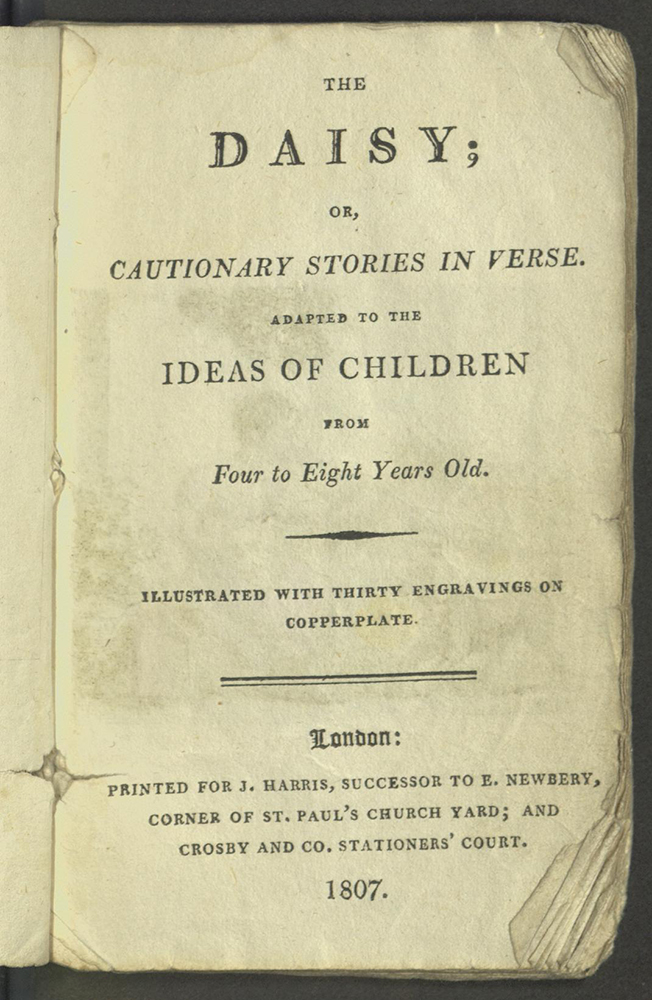

Until the end of the eighteenth century, moral literature for the young focused primarily on religious instruction. But changing ideas about childhood resulted in new parenting styles, with increasing emphasis on empathy, reason, and psychological reward and punishment. Books for children began to speak openly of earthly as well as heavenly rewards for good behavior – happiness, parental love, social approbation, and gifts and treats. Naughtiness, similarly, resulted not only in eternal damnation but also in rebuke, deprivation, social isolation, corporal punishment, injury, and even death. Although many of these books also contained religious instruction, morality and behavior drove much of the narrative, rather than piety and belief.  The most successful book of this sort was The Daisy, or, Cautionary Stories in Verse: Adapted to the Ideas of Children from Four to Eight Years Old, attributed to Elizabeth Turner. First published by John Harris in 1807, it was reprinted in England and America throughout the nineteenth century. Half the poems are about good children who are obedient, kind to their pets and their siblings, speak courteously, study hard at school, and are benefactors of the poor. But the more interesting narratives are driven by conflict, and the most memorable characters are ill-behaved. The Daisy is famous for bad things happening to barely naughty people – burned, poisoned, drowned. It is the epitome of the alarmist books that were parodied first by Hoffman’s Struwwelpeter, and later by Gorey in the Gashlycrumb Tinies. To the 21st-century reader it seems absurd to have threatened such dire outcomes of typical childish misbehavior, especially for such a young audience.

The most successful book of this sort was The Daisy, or, Cautionary Stories in Verse: Adapted to the Ideas of Children from Four to Eight Years Old, attributed to Elizabeth Turner. First published by John Harris in 1807, it was reprinted in England and America throughout the nineteenth century. Half the poems are about good children who are obedient, kind to their pets and their siblings, speak courteously, study hard at school, and are benefactors of the poor. But the more interesting narratives are driven by conflict, and the most memorable characters are ill-behaved. The Daisy is famous for bad things happening to barely naughty people – burned, poisoned, drowned. It is the epitome of the alarmist books that were parodied first by Hoffman’s Struwwelpeter, and later by Gorey in the Gashlycrumb Tinies. To the 21st-century reader it seems absurd to have threatened such dire outcomes of typical childish misbehavior, especially for such a young audience.

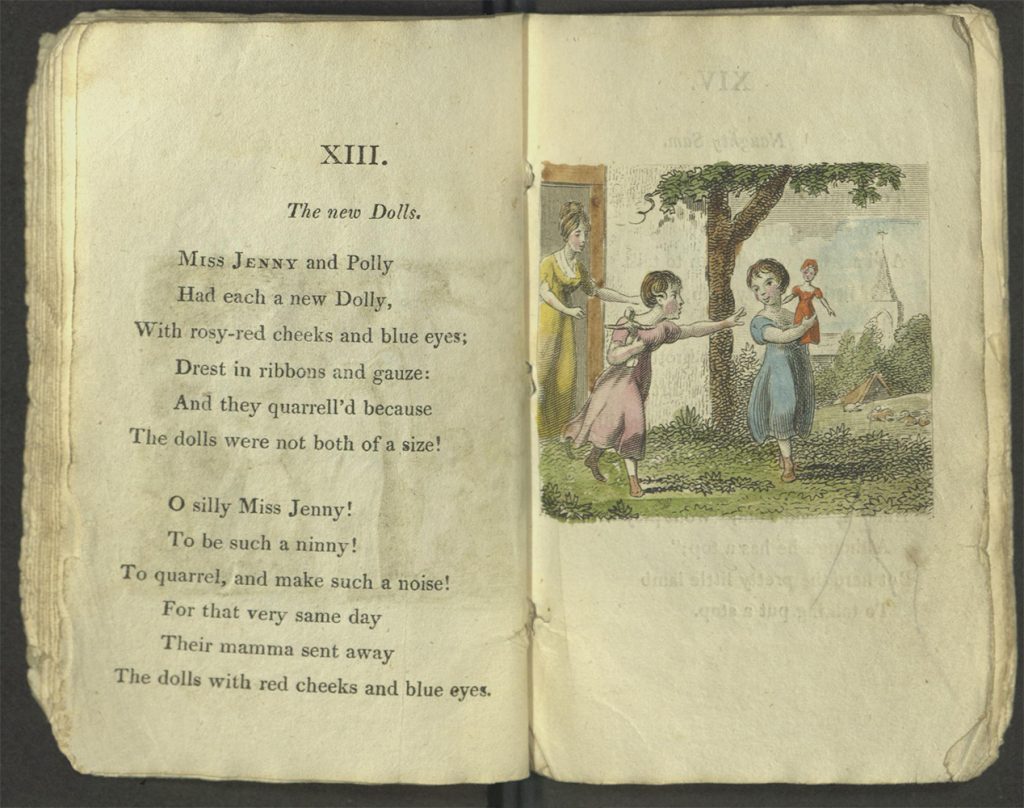

Some of the infractions and punishments do seem reasonable, even to modern feelings. Sisters Jenny and Polly fight over whose new doll is bigger – and their mother takes the dolls away from them.

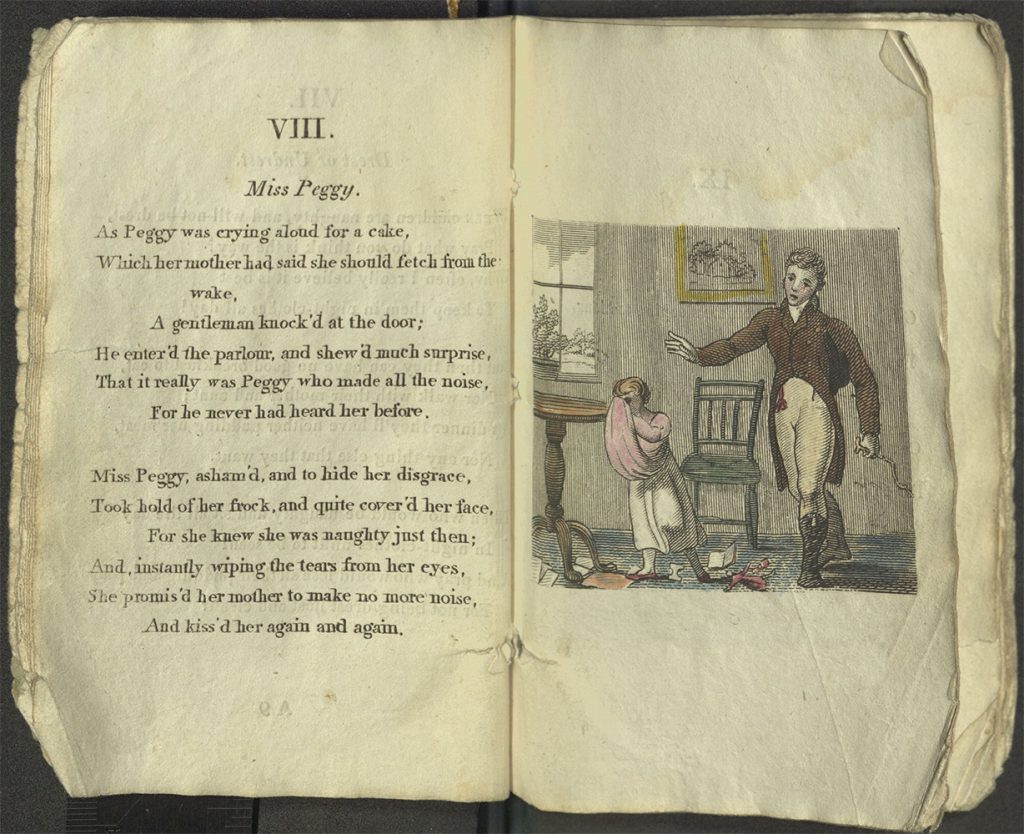

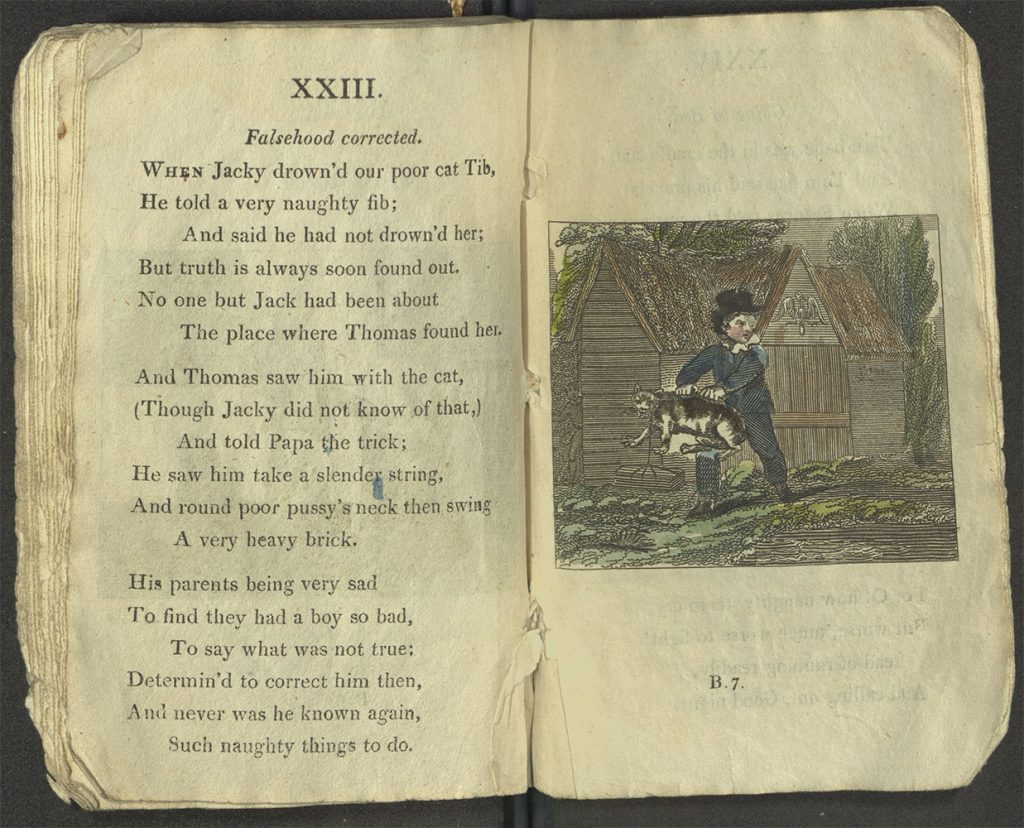

Social pressure is another familiar motive for moral improvement. Miss Peggy is reformed from throwing tantrums by the humiliation of having a gentleman come into the house to learn what all the screaming is about.  We are not, of course, always sympathetic to 19th-century sensibilities. In “Falsehood Corrected” Jacky ties a brick to the cat and drowns it. But he is punished for lying about it – and not for having murdered the family pet.

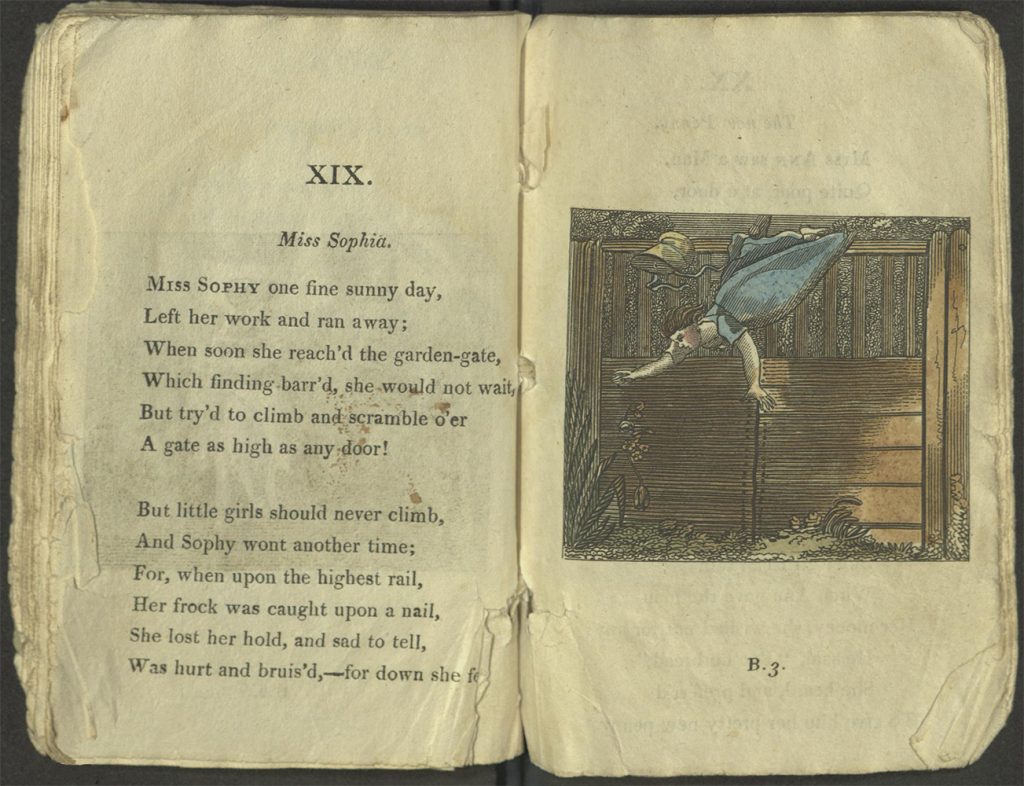

We are not, of course, always sympathetic to 19th-century sensibilities. In “Falsehood Corrected” Jacky ties a brick to the cat and drowns it. But he is punished for lying about it – and not for having murdered the family pet.  Strangest to us are the childish infractions which result in serious injury or death. Miss Sophia neglects her schoolwork and climbs a gate she knows she shouldn’t – and is injured in falling from a gate “as high as any door.”

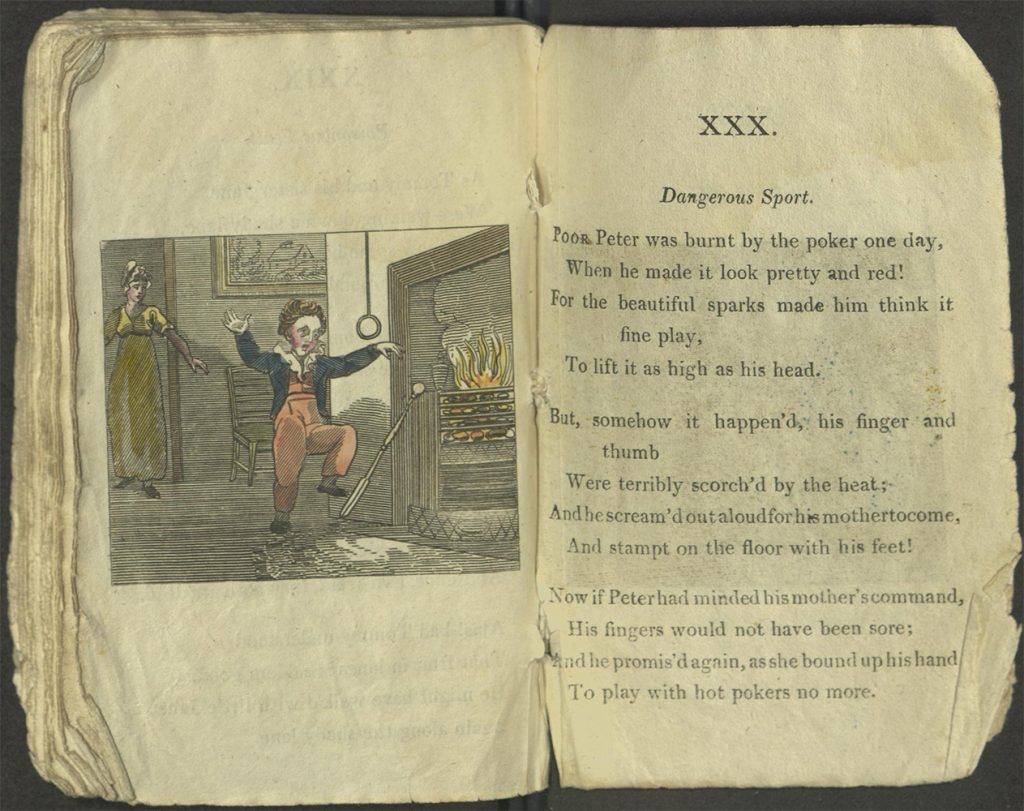

Strangest to us are the childish infractions which result in serious injury or death. Miss Sophia neglects her schoolwork and climbs a gate she knows she shouldn’t – and is injured in falling from a gate “as high as any door.”  Meanwhile, Peter warmed a fireplace poker to red heat, and waved it around until he burned himself – but he would not have been injured if he had obeyed his mother. Disobedience is the greatest, and underlying, offense in most of these stories. Besides recording actions that are inconsiderate, bad-tempered, or foolhardy, the poems stress that the children are doing what they had expressly been told not to do. Even “modern” 19th-century parents, who sympathized, and empathized, and relied upon discussion and reason in correcting their children, felt that those children should obey them immediately and without question.

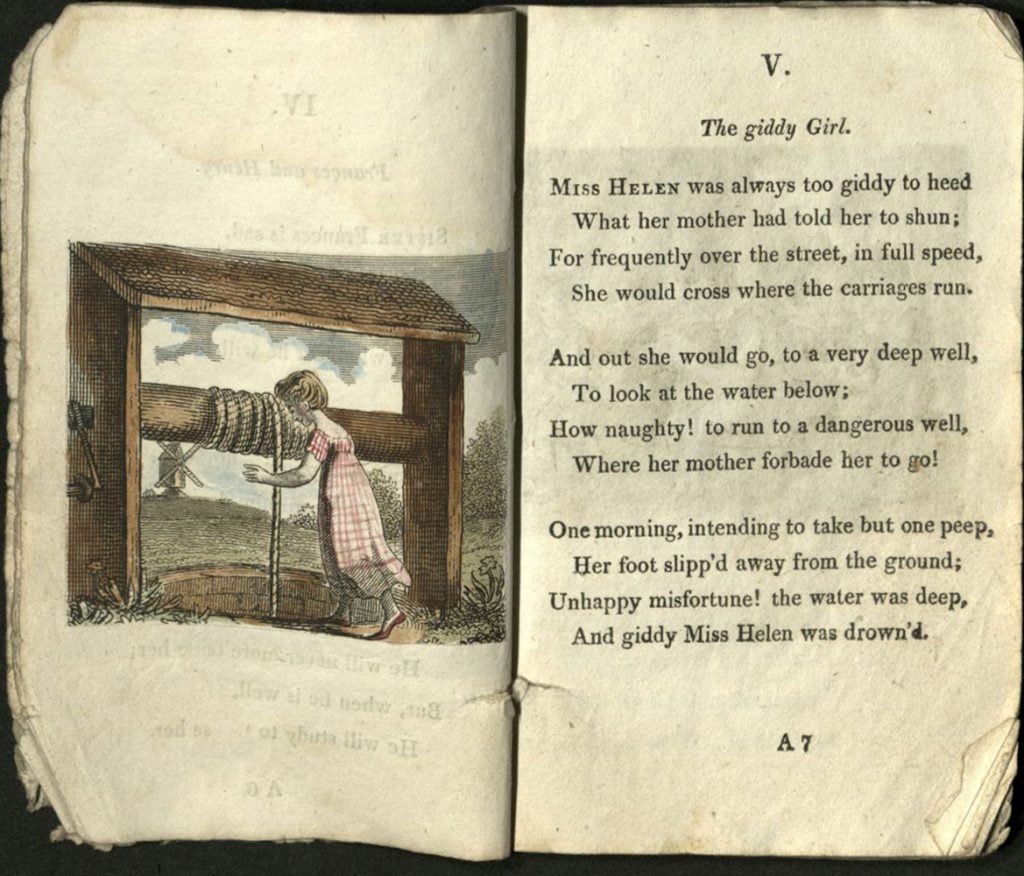

Meanwhile, Peter warmed a fireplace poker to red heat, and waved it around until he burned himself – but he would not have been injured if he had obeyed his mother. Disobedience is the greatest, and underlying, offense in most of these stories. Besides recording actions that are inconsiderate, bad-tempered, or foolhardy, the poems stress that the children are doing what they had expressly been told not to do. Even “modern” 19th-century parents, who sympathized, and empathized, and relied upon discussion and reason in correcting their children, felt that those children should obey them immediately and without question.  As the the result of disobedience, three children in The Daisy are injured – Peter (burned), Sophia (bruised), and Frances, who spins until she is dizzy and hurts herself when she falls. Three die. The fatalities are Tom and Jane, who eat poisonous berries they should have left alone, and Helen, who looks into a well every chance she gets until the day she slips and falls in.

As the the result of disobedience, three children in The Daisy are injured – Peter (burned), Sophia (bruised), and Frances, who spins until she is dizzy and hurts herself when she falls. Three die. The fatalities are Tom and Jane, who eat poisonous berries they should have left alone, and Helen, who looks into a well every chance she gets until the day she slips and falls in.  Helen also used to run across the street, disregarding the danger of carriages. And this gives us a hint that there might actually have been something reasonable about the urgency that drove Elizabeth Turner and contemporary writers to condemn so harshly what seems like simple disobedience and childish foolishness.

Helen also used to run across the street, disregarding the danger of carriages. And this gives us a hint that there might actually have been something reasonable about the urgency that drove Elizabeth Turner and contemporary writers to condemn so harshly what seems like simple disobedience and childish foolishness.

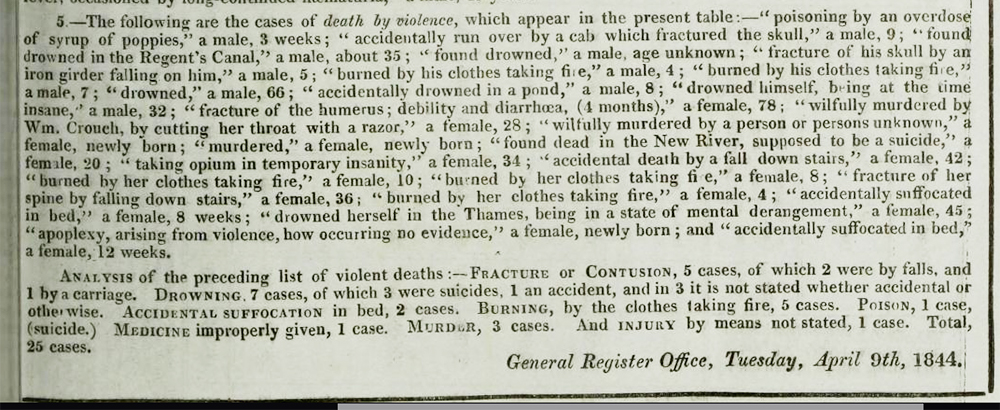

General Register Office; Royal College of Physicians of London. A Table of Mortality for the Metropolis, Shewing the Number of Deaths from All Causes Registered in the Week ending Saturday, 6th April. London: Hartnell, 1844. Scan from the Internet Archive.

The General Register Office for England and Wales, in 1844, began publishing reports for deaths in London in a format that permits one to track causes of mortality for children. I took a quick sample – the first week of each month from that year. Of the 5350 persons between the ages of 0 and 15 who died in those twelve weeks, 102 suffered “Violent deaths” – something other than disease or an inherent medical condition killed them. 40 of those deaths resulted from the children’s clothes catching fire (and 2 more were scalded). Thirteen of the young people drowned. Eleven were run over by carriages. Five fell to their deaths. Nearly 70% of these real children died of one of the causes through which the imaginary children in The Daisy endanger themselves.

I finished my short statistical foray with new sympathy for the “dreadful results” genre of moral literature for the young. It still sounds shrill to me. But I have more specific, evidence-based, ideas now about the perils of living in a time when people cooked with fire, drove horses at high speed through crowded streets, and maintained uncovered wells. The behaviors punished in the poems were demonstrably dangerous. One can hardly blame loving parents from trying what they might to keep their children from harm.

– Marianne Hansen, Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts

Turner, Elizabeth, and John Harris. The Daisy, or, Cautionary Stories in Verse: Adapted to the Ideas of Children from Four to Eight Years Old. London: J. Harris, 1807. We have not yet digitized our copy of The Daisy, but you can get an idea of the book from the 1817 edition at the University of California.

Explore the Table of Mortality for the Metropolis for yourself on the Internet Archive

With the continuing closure of the Library, we are blogging regularly about books from the exhibition, The Girl’s Own Book. Please subscribe or check back here, or follow us on Facebook for notices of new blog posts.

The Tragical Death of A Apple-Pye:

“A is for Apple. B is for Ball,” we say these days. But for two hundred years, English children learning the alphabet grappled instead with apple pie, greed, and interpersonal conflict. Hebrew, Greek and Latin sources provide ancient abecedarian poetry and texts, where the first letter of each line – or verse or stanza – starts with a letter in alphabetical order. Psalm 119 (“Blessed are the undefiled in the way, who walk in the law of the LORD. ” KJV) is abecedarian in Hebrew. St. Augustine’s Psalmus contra partem Donati sets the stanzas in alphabetical order, in Latin. Even Chaucer wrote a carmen secundum ordinem litterarum alphabeti, in English, in honor of the Virgin Mary.

Hebrew, Greek and Latin sources provide ancient abecedarian poetry and texts, where the first letter of each line – or verse or stanza – starts with a letter in alphabetical order. Psalm 119 (“Blessed are the undefiled in the way, who walk in the law of the LORD. ” KJV) is abecedarian in Hebrew. St. Augustine’s Psalmus contra partem Donati sets the stanzas in alphabetical order, in Latin. Even Chaucer wrote a carmen secundum ordinem litterarum alphabeti, in English, in honor of the Virgin Mary.

No one knows when the first ABC poem meant for the youngest readers was created, but Apple Pie was current in England in the 17th century. John Eachard, satirist and doctor of divinity, published a humorous criticism of sermons in the Church in 1671. While abusing preachers who stretch their sermons by elaborating on each letter in a word (REPENT – Readily Earnestly, Presently, Effectually…) he says, “And also why not A Apple-pasty, B bak’d it, C cut it, D divided it, E eat it, F fought for it, G got it, &c. ?” The poem next appears in print in 1743, when it was included in The Child’s New Play-thing, a spelling book that began with several alphabets and ABC poems. It was printed frequently after that in the frenzy of the new market for children’s books.

Many of those “books” were the tiny publications called chapbooks – a single sheet of paper printed on both sides, and folded to make a little sixteen-page pamphlet smaller than the palm of your hand. Our Apple Pye is one of these, roughly 3 1/2 inches tall and 2 1/4 inches wide. It was published around 1800 (it is undated) and the fragile miniature might not have survived, except that it was bound with 14 other chapbooks early on, probably in the eighteen teens.

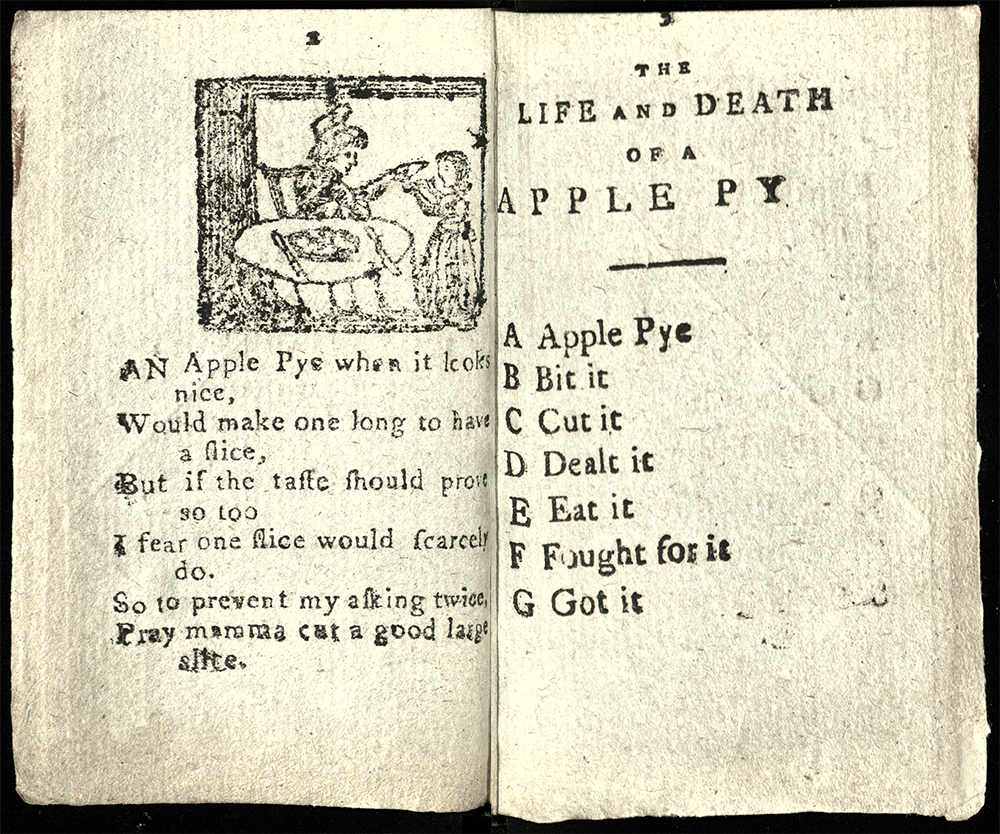

The book includes two alphabet poems, and it begins with a woodcut and a bit of doggerel where a canny child demands a large slice of pie, to save the trouble of asking for a second. The poem proper (The Tragical Death of A Apple-Pye, Who Was Cut in Pieces and Eat by Twenty Five Gentlemen) then begins, and each letter takes some action towards A, the apple pie itself. There is the usual trouble with choosing appropriate words at the end of the alphabet, and X, Y, and Z have to collaborate with Ampersand. The “Twenty-five gentlemen” realize there may not be enough to go around, so they agree to stand in order around the pie and take turns.

There is the usual trouble with choosing appropriate words at the end of the alphabet, and X, Y, and Z have to collaborate with Ampersand. The “Twenty-five gentlemen” realize there may not be enough to go around, so they agree to stand in order around the pie and take turns. But they do not then all use their nicest manners to ensure a fair distribution of the meal. The second alphabet poem, A Curious Discourse that Passed Between the Twenty-five Letters at Dinner-Time, starts with A, like the little girl in the opening verse, asking for “a good, large slice.”

But they do not then all use their nicest manners to ensure a fair distribution of the meal. The second alphabet poem, A Curious Discourse that Passed Between the Twenty-five Letters at Dinner-Time, starts with A, like the little girl in the opening verse, asking for “a good, large slice.” Every letter has its preferences, although most of them just want a lot of pie.

Every letter has its preferences, although most of them just want a lot of pie. Predictably, by the time it is Y’s turn, he eats the last piece, and Z and Ampersand have to lick the dish. John Evans, the printer/publisher, then inserted an advertisement for his other books for “little readers,” complete with his shop address.

Predictably, by the time it is Y’s turn, he eats the last piece, and Z and Ampersand have to lick the dish. John Evans, the printer/publisher, then inserted an advertisement for his other books for “little readers,” complete with his shop address. Evans still had three small pages to fill, so he added a woodcut of the imaginary old woman who made the pie in the poem, and stated she would supply a similar treat to good children. But since good people always pray before meals, he included a grace for the children to learn – to demonstrate that they deserved a pie. On the final page, he printed a postprandial grace and the Lord’s Prayer.

Evans still had three small pages to fill, so he added a woodcut of the imaginary old woman who made the pie in the poem, and stated she would supply a similar treat to good children. But since good people always pray before meals, he included a grace for the children to learn – to demonstrate that they deserved a pie. On the final page, he printed a postprandial grace and the Lord’s Prayer. Our copy of The Tragical Death is part of the Ellery Yale Wood Collection of Books for Young Readers. It has been digitized and is available for your perusal on the Internet Archive.

Our copy of The Tragical Death is part of the Ellery Yale Wood Collection of Books for Young Readers. It has been digitized and is available for your perusal on the Internet Archive.

The Tragical Death of a Apple-Pye, Who Was Cut in Pieces and Eat by Twenty Five Gentlemen: With Whom All Little People Ought to Be Very Well Acquainted. London: Printed by John Evans, 42, Long-lane, West-smithfield, c.1800.

With the continuing closure of the Library, we are blogging regularly about books from the exhibition, The Girl’s Own Book. Please subscribe or check back here, or follow us on Facebook for notices of new blogs.

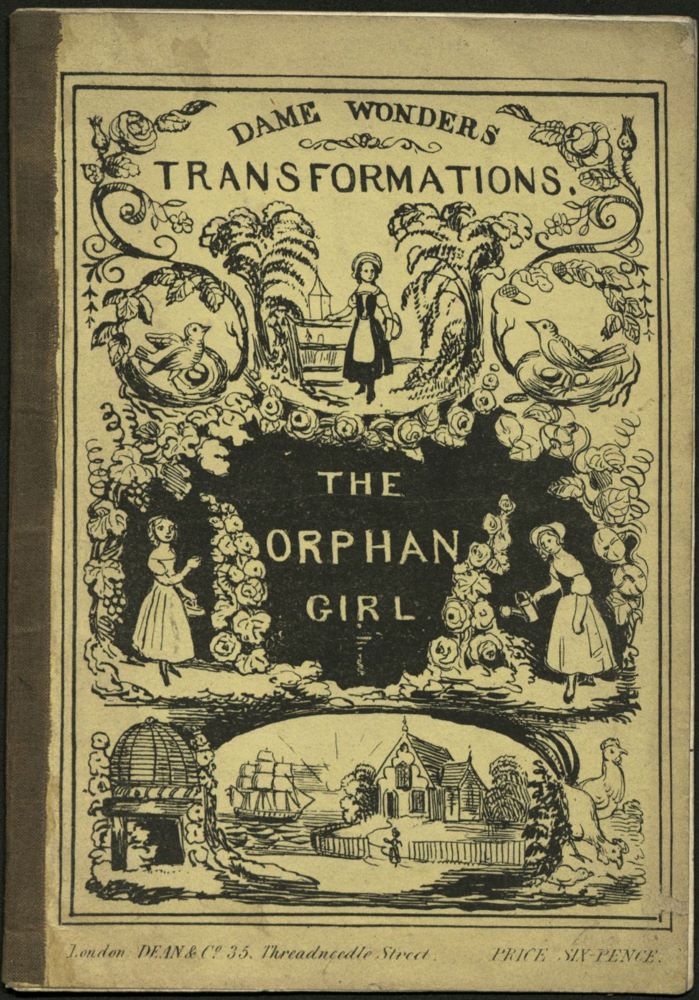

Transformations of Images and Texts – The Orphan Girl

Dean & Co. was an early and prolific publisher of toy and movable books for children: pop-ups, pantomime books, “peepshow” or tunnel books. Their first line of novelty books was the series Dame Wonder’s Transformations, books with a hole cut in each page through which the face of the main character appears, surrounded by the events of the story. The Orphan Girl, published between 1843 and 1845, is a charming example of this technology.

The Orphan Girl, published between 1843 and 1845, is a charming example of this technology.

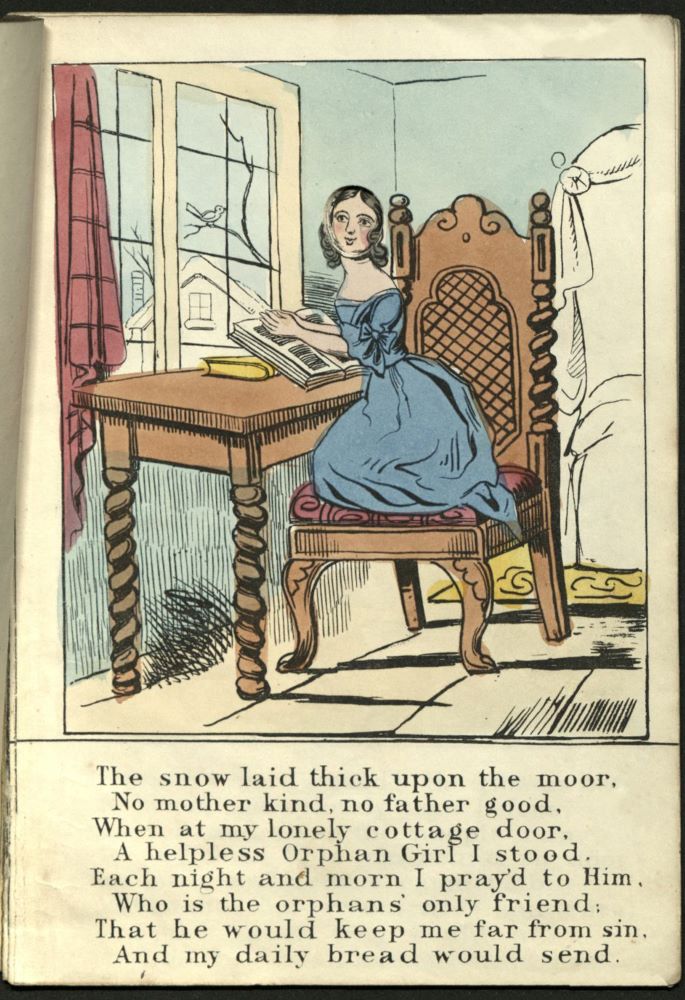

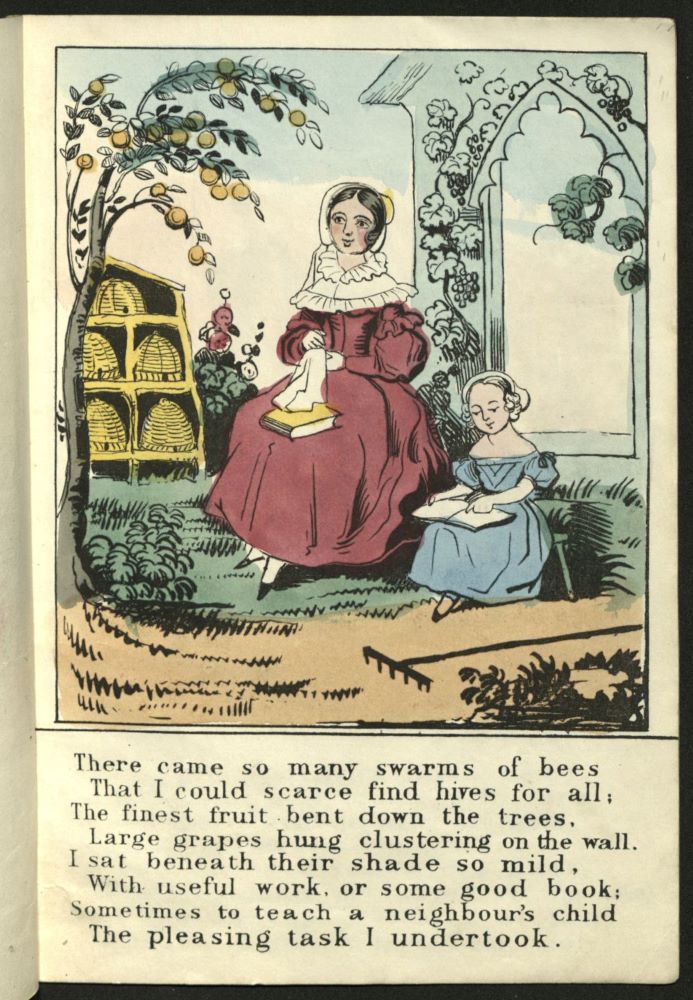

The story is told in the first person by the “orphan girl”, who appears to be in her mid-to late teens at the beginning of the book. She is left alone, although in possession of a cottage, and she calls upon God to keep her from sin and to supply her needs.  As a result of her earnest piety, her garden provides abundant bouquets which she sells to the wealthy.

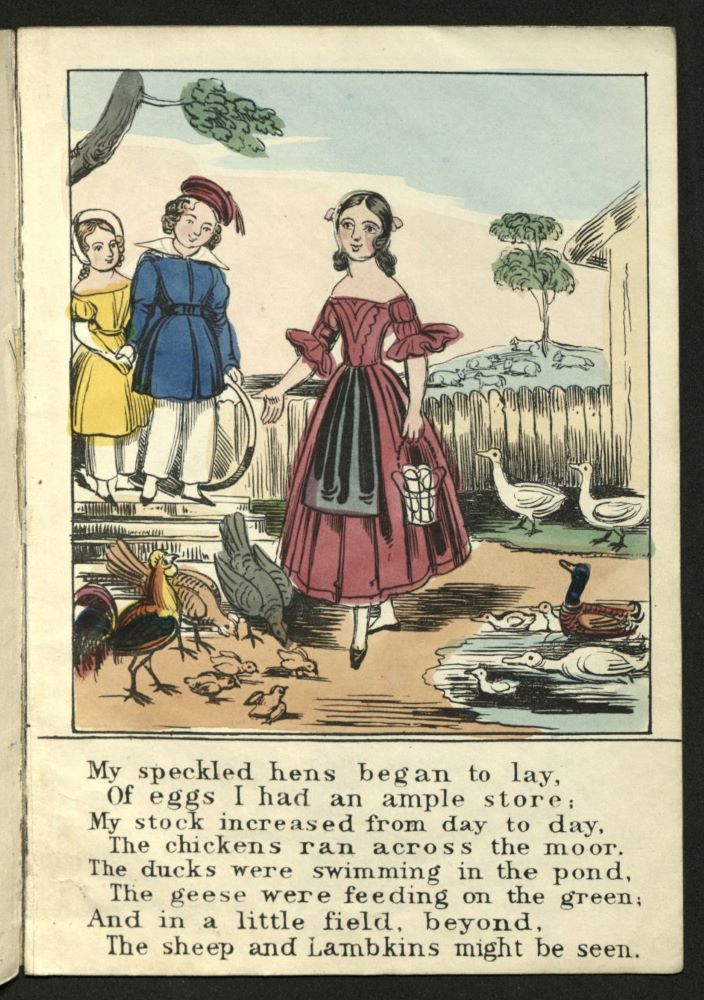

As a result of her earnest piety, her garden provides abundant bouquets which she sells to the wealthy.  In addition, her domestic fowl and sheep increase prodigiously, bees swarm to her home, and her fruit trees and vines bear heavily.

In addition, her domestic fowl and sheep increase prodigiously, bees swarm to her home, and her fruit trees and vines bear heavily.  She occasionally teaches a neighbor’s child to read, apparently as a leisure activity.

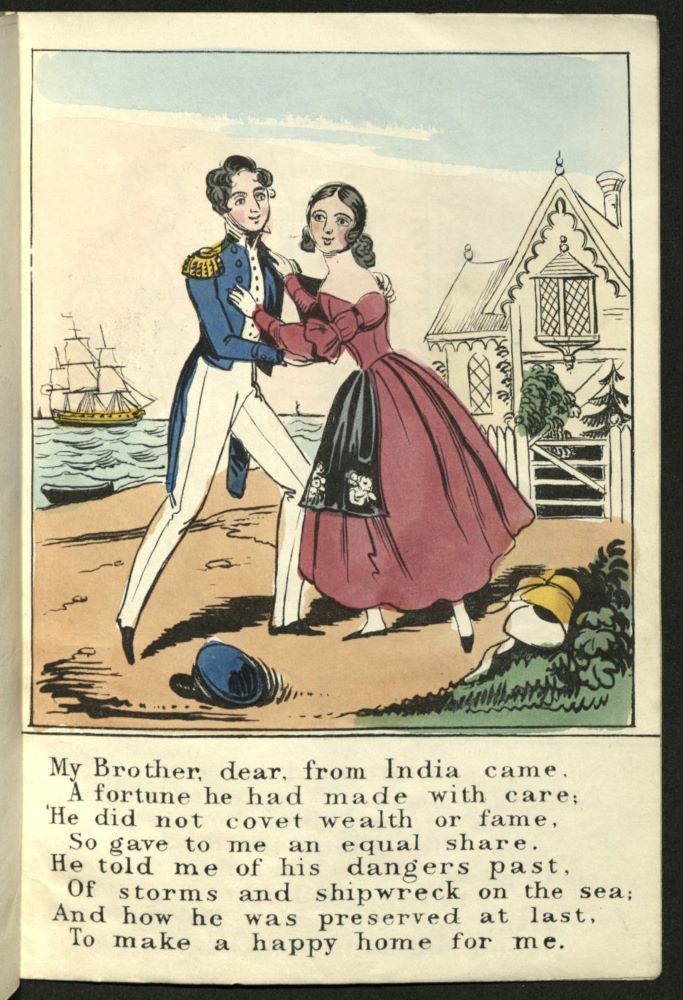

She occasionally teaches a neighbor’s child to read, apparently as a leisure activity.  Suddenly, her brother returns from India, having made a fortune, and provides the means for the two of them to live comfortably in the cottage.

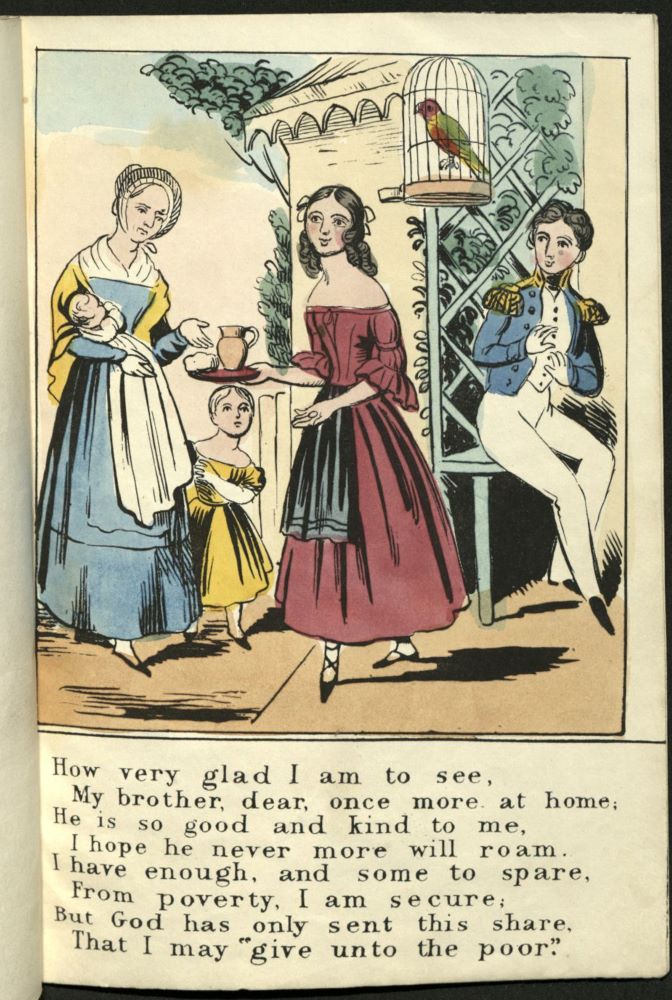

Suddenly, her brother returns from India, having made a fortune, and provides the means for the two of them to live comfortably in the cottage.  In the last scene, supplied abundantly herself, she gives bread and drink to an impoverished neighbor.

In the last scene, supplied abundantly herself, she gives bread and drink to an impoverished neighbor. The narrative is related to the most famous children’s book of the eighteenth century, Little Goody Two-Shoes, although in The Orphan Girl, the account is condensed to an extreme. The original, first published in 1765, tells the story of a sister and brother whose parent die when the children are small. They are separated, and the story follows the sister who lives at first in extreme poverty in the country, gradually gaining the respect and trust of her fellow villagers. By the time she is in her early teens she supports herself by going house to house daily, teaching younger children to read. When the schoolmistress retires, she is chosen to replace her. Her competence and kindness induce a local gentleman first to employ, then to woo her. Their wedding is enlivened by the return of her now wealthy brother, and she lives afterward as a model of prudence, piety, and effective charity. The Libraries do not, unfortunately, have an early copy of the book, but you can read it on the Internet Archive.

The narrative is related to the most famous children’s book of the eighteenth century, Little Goody Two-Shoes, although in The Orphan Girl, the account is condensed to an extreme. The original, first published in 1765, tells the story of a sister and brother whose parent die when the children are small. They are separated, and the story follows the sister who lives at first in extreme poverty in the country, gradually gaining the respect and trust of her fellow villagers. By the time she is in her early teens she supports herself by going house to house daily, teaching younger children to read. When the schoolmistress retires, she is chosen to replace her. Her competence and kindness induce a local gentleman first to employ, then to woo her. Their wedding is enlivened by the return of her now wealthy brother, and she lives afterward as a model of prudence, piety, and effective charity. The Libraries do not, unfortunately, have an early copy of the book, but you can read it on the Internet Archive.

Of course, if you reduce a story from 100 plus pages to a bare six images you must simplify the narrative. Goody Two-Shoes appeared in dozens of later, shorter versions, many of which suggest that the reader was expected already to know the story. But the differences in these two accounts give us an opportunity to reflect on the lessons conveyed by books to their young readers. The “orphan girl” is devout and trusts God, and she is rewarded for her faith and piety by prosperity, without any effort beyond prayer. Although Goody Two-Shoes also conveyed numerous religious messages, it featured a protagonist who made her way in the world though dogged hard work, good nature, and intelligence. Both are historically acceptable role models – but what a difference in the influences the two might have on a young female reader.

The Orphan Girl. London: Dean & Co., 35 Threadneedle Street, 1843-1845

The Orphan Girl. London: Dean & Co., 35 Threadneedle Street, 1843-1845

The History of Little Fanny – Make Your Own Paper Dolls

Gallery

This gallery contains 19 photos.

The History of Little Fanny, Exemplified in a Series of Figures was offered in 1810 by the publisher S. and J. Fuller at their magnificent Temple of Fancy, a London emporium of artists’ supplies, instruction books on drawing and painting, … Continue reading

Madame Curie’s Forgotten Visit to Bryn Mawr

By Rebecca Kelly-Bowditch, Friends of the Library Intern, Summer, 2019.

Recently, a researcher at Northwestern University contacted Special Collections requesting all of our information regarding Marie Curie’s visit to Philadelphia and Bryn Mawr in the spring of 1921. This was something of a surprise, as no one here knew that the famous scientist had visited the college. Online, records abound of Curie’s time in Philadelphia; as do records of a speech M. Carey Thomas gave in New York to welcome her to America. Looking through our Archives, I was also able to find a substantial amount of correspondence from Thomas planning for Curie’s visit. However, if Curie had come to Bryn Mawr, why didn’t anyone know about it? I began reading Thomas’ letters to try to find out the story behind this visit.

Thomas had grand plans for Marie Curie’s visit, and was heavily involved in planning her time in Philadelphia. The two-time Nobel-winning French scientist exemplified to Thomas the ideal of the college woman: Curie’s education and determination enabled her to discover radium and earn international respect for her contributions to the understanding of radioactivity, despite her gender. To Thomas, Curie’s visit was the chance to both inspire American college women and to bolster her ongoing battle for women’s rights. Marie Curie, however, was not one to flaunt her fame. In fact, she had a deep distaste for the limelight and avoided public engagements whenever possible. She was of the opinion that science was for the betterment of society, not the betterment of an individual. She and her late husband, Pierre, had begun their work in a run-down shed in 1897; their aversion to fame and her refusal to patent the radium production process meant that by 1921, Curie’s lab was still inadequate and her supply of radium was dwindling. An American magazine editor and socialite, Mrs. William Brown Meloney, had learned of Curie’s struggles and contrived to raise the funds needed to continue her work; a single gram of radium cost over $100,000. Unfortunately for the reclusive scientist, Meloney’s plans centered on a very public appeal to the women of America. Using her magazine, The Delineator, as a platform, she stressed the significant impact which American women as a group could have on the future of science by each contributing small amounts of money to Curie’s research. To facilitate the fundraising, Meloney formed the Marie Curie Radium Fund, led by two Committees: one of well-known scientists (all men) and one of wealthy, philanthropic women.

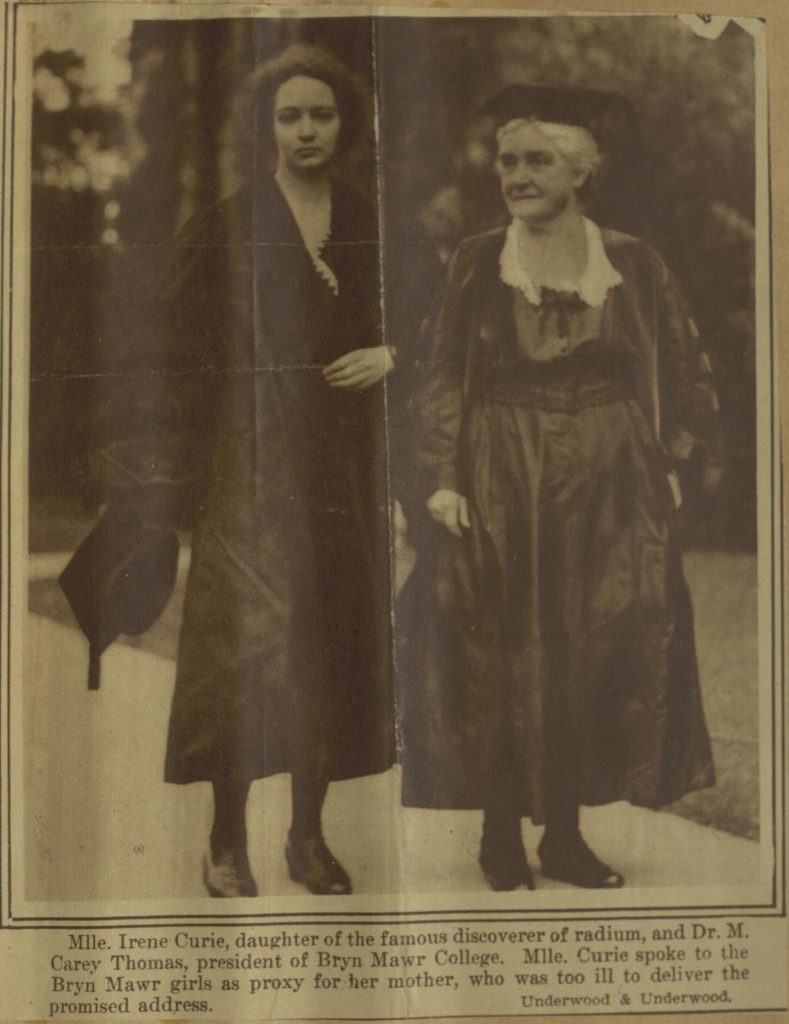

Mrs. Meloney was as extroverted as Marie Curie was introverted. Despite their opposite personalities, the two became close friends and Meloney convinced Curie to travel to America to support the fundraising being done in her name. Curie would spend seven weeks in May and June traveling the country and receiving honors, culminating in the presentation of a gram of radium by President Harding. The Radium Fund Committee was responsible for planning Curie’s itinerary, and one of the major events was to be a grand assembly at Carnegie Hall, where Curie would “be welcomed by the university women of the United States.” M. Carey Thomas and other notable women were to give speeches. Meloney accompanied the scientist throughout the trip, along with Curie’s daughters, Irene (23) and Eve (16). Irene was by now working as her mother’s lab assistant; she would later go on to win her own Nobel Prize.

While the Radium Fund was based in New York, local branches were formed in other cities. M. Carey Thomas was chosen to organize the Philadelphia Committee, serving both as Treasurer and Chairman. Thomas embraced her role with enthusiasm and recruited influential Philadelphians as Committee members, including two women doctors. In the months leading up to Curie’s visit, much of Thomas’ time was spent soliciting donations and corresponding about fundraising efforts. In addition to requesting donations from wealthy Philadelphians, Thomas asked all Bryn Mawr students to donate $1. Despite initial concerns about the Philadelphia Committee’s ability to reach their goal of $5000, they ended up contributing a total of $7489.74.

While the Radium Fund was based in New York, local branches were formed in other cities. M. Carey Thomas was chosen to organize the Philadelphia Committee, serving both as Treasurer and Chairman. Thomas embraced her role with enthusiasm and recruited influential Philadelphians as Committee members, including two women doctors. In the months leading up to Curie’s visit, much of Thomas’ time was spent soliciting donations and corresponding about fundraising efforts. In addition to requesting donations from wealthy Philadelphians, Thomas asked all Bryn Mawr students to donate $1. Despite initial concerns about the Philadelphia Committee’s ability to reach their goal of $5000, they ended up contributing a total of $7489.74.

In addition to fundraising, Thomas took charge of planning Curie’s itinerary for Philadelphia. Frequently corresponding with Meloney and with other members of the Philadelphia Committee, she arranged for Curie, her daughters, and Meloney to stay with her at the Deanery for May 23rd and 24th. She planned a full schedule for the scientist, with many opportunities for Curie to appreciate Bryn Mawr. On the 23rd, the group would arrive and have lunch in Philadelphia before touring the Women’s Medical College of Philadelphia where Curie was to be awarded an honorary degree, followed by another honorary degree conferral at the University of Pennsylvania, dinner at Bryn Mawr, and finally a ceremony at the College of Physicians. Curie would spend the night at the Deanery, then visit several radium laboratories the next morning. Thomas planned a large garden party to be held in the Deanery garden that afternoon, and that night the American Philosophical Society would also honor Madame Curie.

Unfortunately for Thomas, plans quickly began to fall through once Curie arrived in America. On May 12th, Thomas wrote to Meloney to confirm cancellation of the radium laboratory trips, noting her disappointment that luncheon at Bryn Mawr had also been cancelled. The garden party was still scheduled as planned, but Thomas hoped to secure more of the scientist’s time. She entreated Meloney to convince Curie to substitute a “brief lecture, or half a brief lecture, in French” for Bryn Mawr students, and asked her to explain to Curie that the only reason why the college was not conferring upon her an honorary degree was because the founders had not granted that power. A couple days later, Thomas wrote to her Vice-Chairman, Dr. John G. Clark, to explain the reason behind the cancellations: Curie had decided to secretly visit the Welsbach plant in New Jersey, which produced mesothorium (an isotope of radium).

May 19th brought more bad news. Thomas wrote Dr. Martha Tracy of the Women’s Medical College to inform her of changes to the itinerary. Curie’s heart had failed, and “she had on Tuesday night two very serious heart attacks.” As a result, all functions were to be cancelled or minimized as much as possible. Curie would arrive at ceremonies just in time to receive the honorary degrees or awards, then leave immediately. Her daughters would attend the full ceremonies and other events in her stead. Curie managed to attend some of the award ceremonies and did indeed visit the Welsbach plant, where she was presented with 50 milligrams of mesothorium, but she arrived late to Philadelphia and her daughters stood in for her on many occasions. Thomas was forced to concede most of her grand plans for Curie’s visit, but the much-anticipated garden party still took place. According to the Bryn Mawr College News of June 1st, 1921 there were 700 guests in attendance, but Curie was too ill to receive or speak and was forced to leave the party early. Her daughter and lab assistant Irene stepped in on the same day to present a lecture to Bryn Mawr students about her mother’s work and discoveries.

Although Thomas and Curie did not end up interacting as much as the former had hoped, they did correspond occasionally after the trip. Thomas sent Curie some newspaper cuttings which she thought she would be interested in, and there is a record of Thomas receiving a card and picture from Curie addressed to the students of Bryn Mawr. Thomas and Meloney continued to write as well, and in 1929 Meloney wrote telling Thomas of a recent discussion with Curie in which the scientist had spoken of her fond memories of meeting Thomas.

Bauhaus at Bryn Mawr: Museum Studies Praxis Intern Organizes Fall Exhibition

by Rachel Grand (BMC ’21)

Student curator Rachel Grand ’21 at opening of ReconTEXTILEize, the 360 course cluster’s exhibition that helped prepare her to organize her own exhibition this fall.

I began my internship with Special Collections as part of the Museum Studies Praxis course, where students find placements in local museums for a practical learning experience. I was placed with a History of Art PhD candidate, Nina Blomfield, who is curating an exhibition in the fall on Lockwood de Forest’s decorative arts program for the College. My initial assignment was to help with her research, but it grew into an opportunity to curate my own smaller exhibition in conjunction with hers on Marcel Breuer, another artist commissioned to design furniture for the College. Compared to my past internships, I felt extremely fortunate for this opportunity with Special Collections because of the real responsibilities that were entrusted to me. In this internship, I felt that the research that I produced for Nina was valued and impactful, and the exhibition that I was able to curate myself, has taught me an invaluable amount about curatorial work. Because of the research opportunities afforded to me in Special Collections, I learned more about the history of Bryn Mawr College than I ever expected to know about my temporary home.

Lockwood de Forest was a designer and architect who first came to Bryn Mawr College in the 1890s. His boss, and friend, was none other than M. Carey Thomas, for whom he designed and decorated a significant portion of her residence and other parts of campus. De Forest is not a well-known name nowadays among students and faculty, compared to M. Carey Thomas, so it was surprising to learn that his architectural touch is all over the College, from the campus center and health center, to the ceiling of the Great Hall! When I walk around on campus now, knowing the history of the buildings enforces a sense of home. While reading correspondence between de Forest and Thomas, I got a sense of Thomas’ strong will, in regard to both interior decoration as well as the future of the college, which provided me with an educated perspective, amidst the controversy surrounding the renaming of Old Library.

The second artist that I studied, Marcel Breuer, was commissioned for a specific project on campus. When Rhoads was built in 1937, he was approached by the college to design a set of furniture for the new dorm rooms. Marcel Breuer was a famous designer and architect who was trained at the Bauhaus, a radically modern art school in Weimar Germany.

In order to learn more about Breuer’s furniture, I looked through the college’s archives. As I searched, I could not help but notice how the College used to place an emphasis on Bryn Mawr being “male friendly.” The yearbook from 1939 boasted that women who lived in Rhoads were more likely to be engaged (to men) than any other dorm. Photographs of students in Rhoads dining hall in the 1960s depicted at least one man in each group of smiling students.

I am told that the student body here has changed in recent years and learning more about the college’s history has only confirmed that. Today, Bryn Mawr students would not tolerate M. Carey Thomas, her elaborate expenditures, nor yearbooks boasting their marriageability. It was very impactful to be able to situate myself, as a student, in the timeline of Bryn Mawr’s past through this research at Special Collections.

Rachel’s exhibition, Bauhaus at Bryn Mawr: Marcel Breuer’s Furniture for Rhoads, opens October 24 in the Coombe Suite Display Case on the second floor of Canaday Library.

Happy Holidays!

In January 1823 the London Magazine published Charles Lamb‘s humorous three-page essay “Rejoicing Upon the New Year’s Coming of Age.” It imagined the feast given by the New Year, and attended by 365 guests: April’s Fool, May Day, Christmas, Lord Mayor’s Day, and all the rest. By 1824, Lamb had recast his work as a poem for children, and it was printed with six pages of engravings as The New Year’s Feast on His Coming of Age. In honor of the holidays, we are sharing the copy that come to the Library as part of the Ellery Yale Wood Collection of Children’s Books and Young Adult Literature. It begins:

The Old Year being dead, the young Lord, New Year’s Day,

Determined on giving, for once and away,

A treat to his friends; and that none might be slighted,

All the days in the year to the Feast were invited.

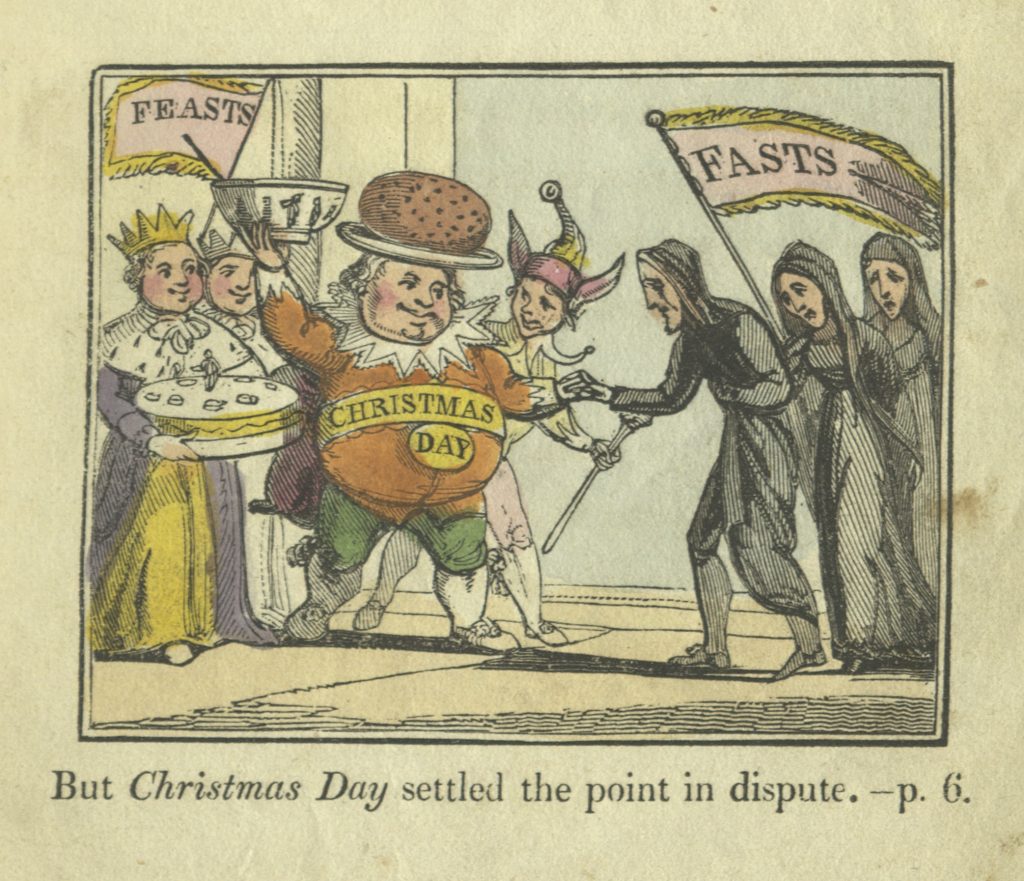

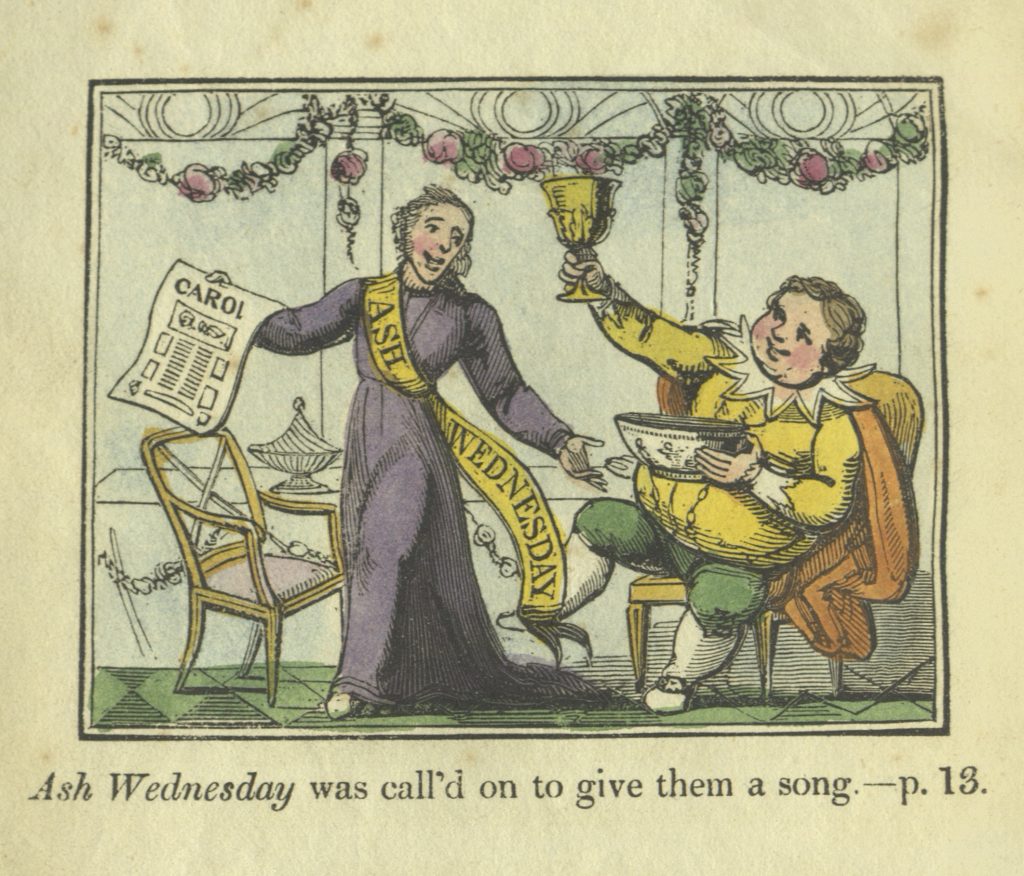

After some squabbling about whether the sad, depressing fast days should be included, Christmas Day prevails and they are invited. It turns out Christmas is not just being kind – he intends to get Ash Wednesday drunk and see what happens.

After some squabbling about whether the sad, depressing fast days should be included, Christmas Day prevails and they are invited. It turns out Christmas is not just being kind – he intends to get Ash Wednesday drunk and see what happens.

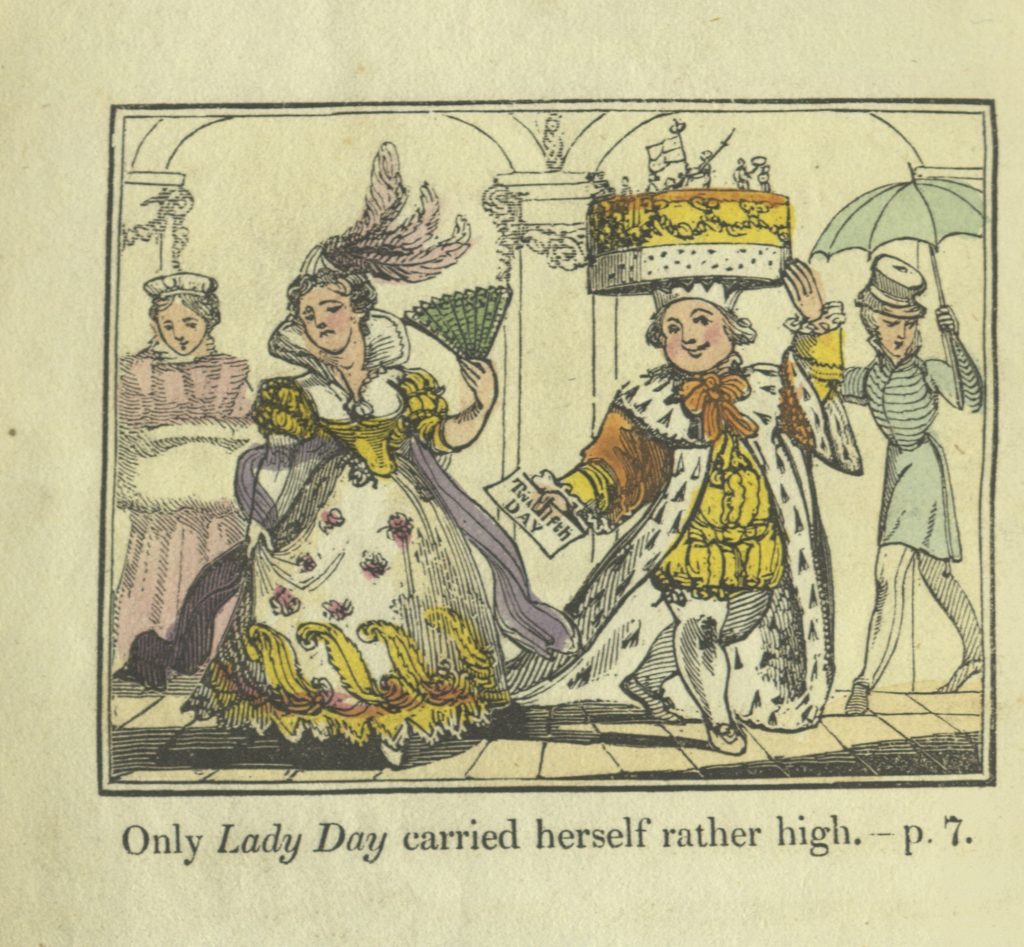

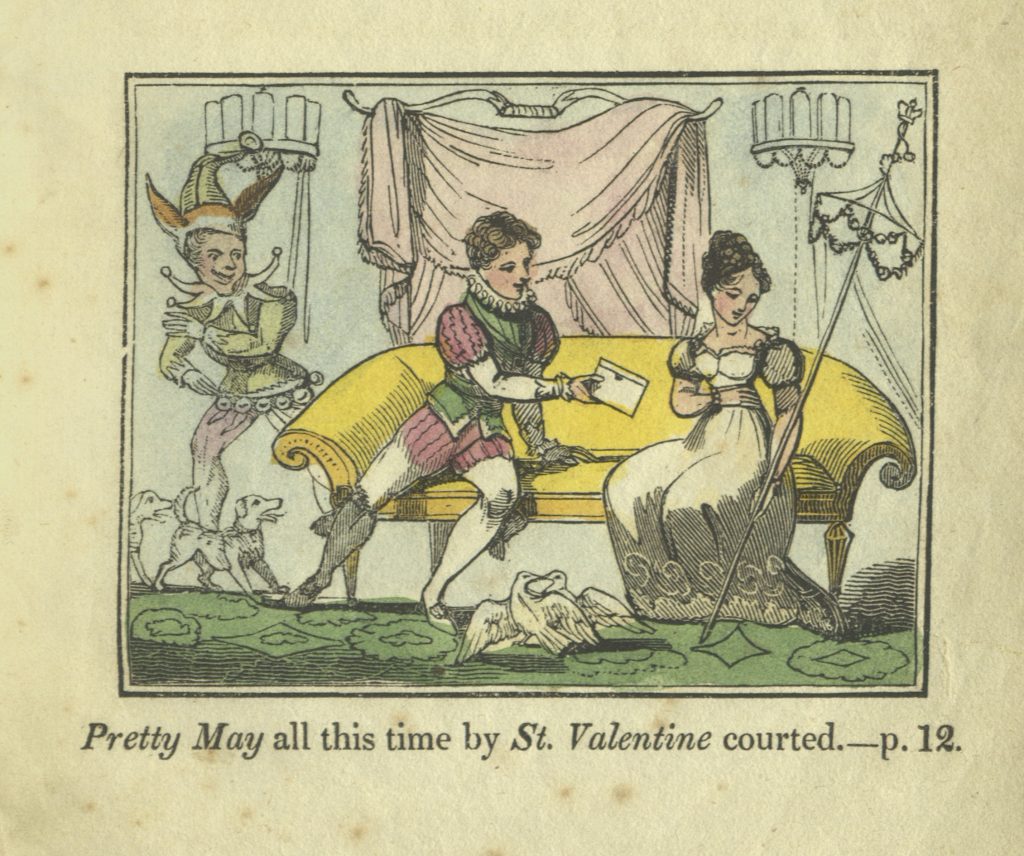

Twelfth Day (usually called Twelfth Night) is the epitome of style, and May Day and St. Valentine cozy up on a sofa.

Twelfth Day (usually called Twelfth Night) is the epitome of style, and May Day and St. Valentine cozy up on a sofa.

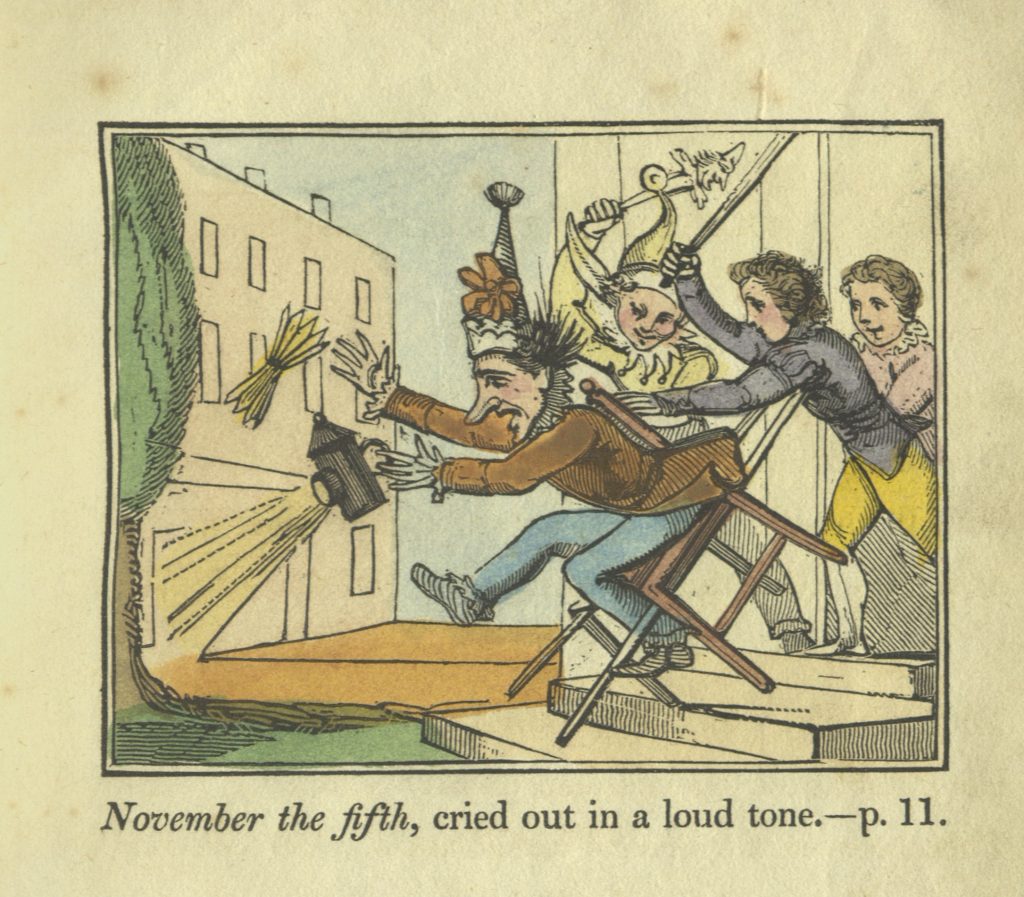

New Year’s speech of welcome is rudely interrupted by November 5 (the anniversary of the discovery of the Gunpowder Plot, Bonfire Day), and the guests take it upon themselves to kick the malcontent out into the street.

New Year’s speech of welcome is rudely interrupted by November 5 (the anniversary of the discovery of the Gunpowder Plot, Bonfire Day), and the guests take it upon themselves to kick the malcontent out into the street.

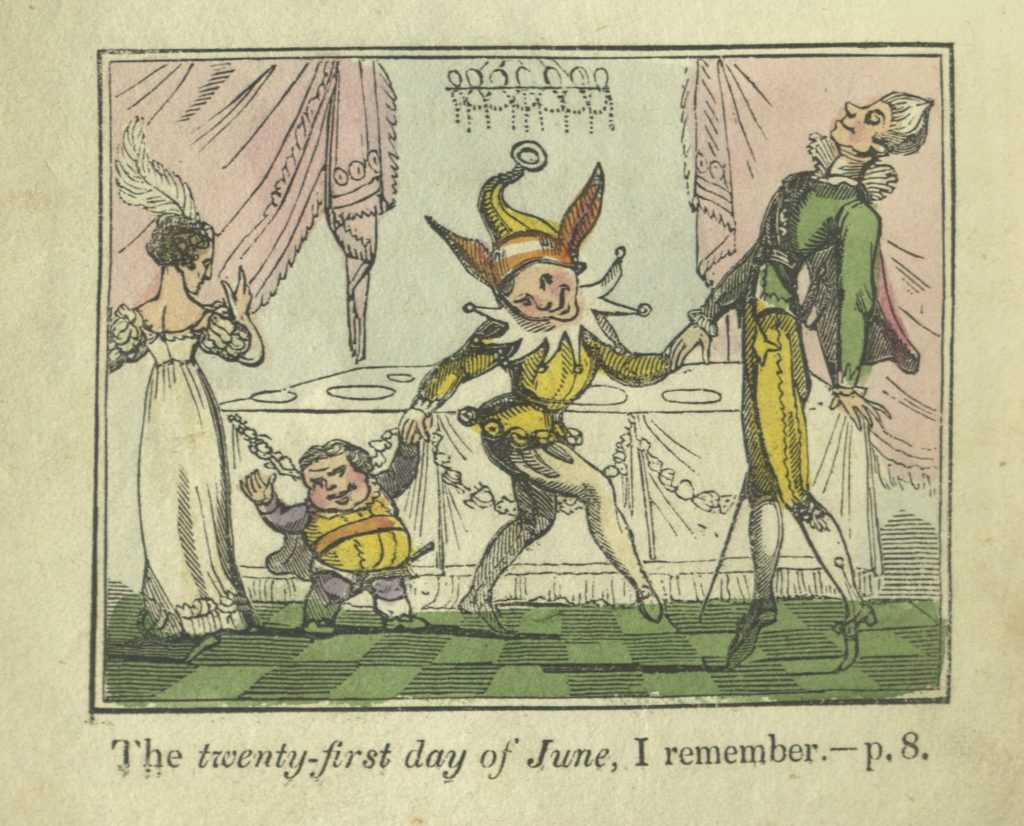

April Fool, who appears in many of these engravings, serves as chief jester and master of ceremonies for the feast. He seats the distant solstices together at the table:

April Fool, who appears in many of these engravings, serves as chief jester and master of ceremonies for the feast. He seats the distant solstices together at the table:

The twenty-first day of June, I remember,

The twenty-first day of June, I remember,

He sat next the twenty-first day of December;

The former the latter contemptuously eyed,

Like a May-pole a[nd] marrow-bone placed side by side.

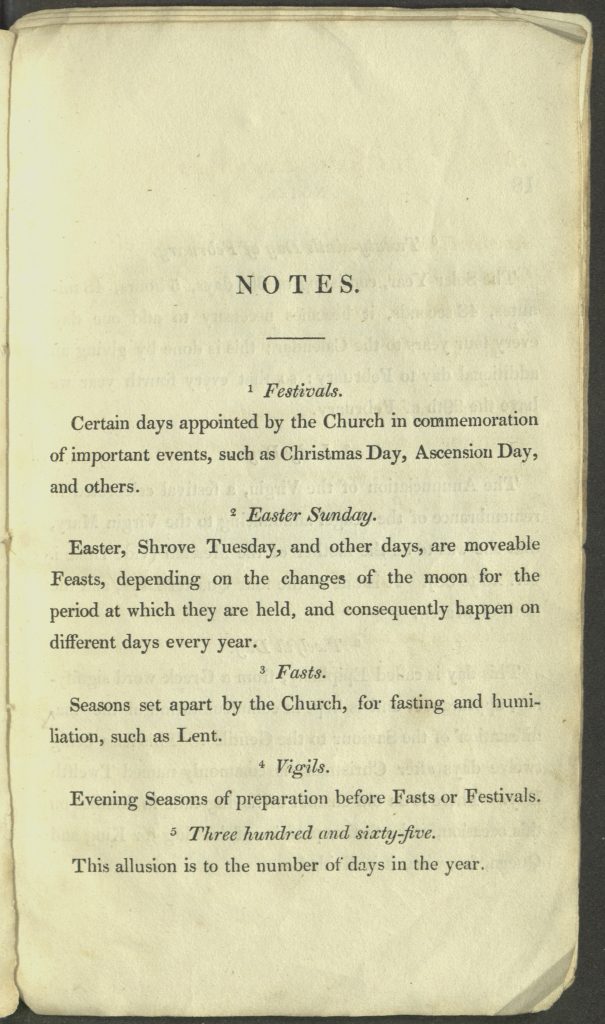

Fortunately for the modern reader, an appendix is provided “designed to assist the juvenile capacity in understanding the allusions in the Poem.” These notes explain, for example, why August the Twelfth and St. George’s Day quarrel over who is to propose the King’s health – George IV’s birthday had come to be celebrated not on his natal day, but on St. George’s feast day, April 23. Other notes are equally useful, explaining Quarter Days, Ember Days, Rogation Day, Septuagesima, and the Greek Kalends (which turn out not to exist).

Once Christmas has plied Ash Wednesday with wassail, both entertain the company with song.

Once Christmas has plied Ash Wednesday with wassail, both entertain the company with song.

Music and conversation follow, and after further revels, the guests depart for their homes. Watchmen (the Vigils) accompany those who needed assistance.

Music and conversation follow, and after further revels, the guests depart for their homes. Watchmen (the Vigils) accompany those who needed assistance.

Another old Vigil, a stout-made patrol.

Called the Eve of St. Christopher’s, jolly old soul,

Perceiving Ash Wednesday inclining to roam,

Took him up on his shoulders and carried him home.

You can read the book for yourself (and find out what Christmas and Ash Wednesday sang, and who went scandalously home with whom) on the Internet Archive. We have digitized our handsome, hand-colored copy, and loaded it into this vast public library at https://archive.org/details/NewYearsFeastOnHisComingOfAge1824. The original essay is also available at https://archive.org/details/londonmagazine11taylgoog/page/n16.

You can read the book for yourself (and find out what Christmas and Ash Wednesday sang, and who went scandalously home with whom) on the Internet Archive. We have digitized our handsome, hand-colored copy, and loaded it into this vast public library at https://archive.org/details/NewYearsFeastOnHisComingOfAge1824. The original essay is also available at https://archive.org/details/londonmagazine11taylgoog/page/n16.

We wish you and yours the happiest of holidays and a very happy, healthy new year!

On Gardens Speak by Tania El Khoury

REFLECTION by Tanjuma Haque (BMC 2021)

Even though I had already seen the set-up of Gardens Speak before and knew what was going to happen, the moment I stepped in through the doors, everything felt completely alien. The lights were dim on the two pews where the ten of us went and sat as the guide handed us one card each person.

As I entered the space where the garden with the graves was made, honestly, I was scared for a moment or two. Since we all had to take off our shoes before we entered the space, the soil was cold under my bare feet as I searched for the person’s grave whose headstone’s picture was on my card.

The humming noise clarified into words as I dug the soil near the headstone with my hands. I put my head next to the pillow with their name, in front of the headstone, and lied and listened quietly. I heard Mustafa’s narrative of how everything was before and after he died, spoken by a man in the first person.

I had taken a Middle Eastern Politics class last semester and I had seen movies from the Middle East that showcased the different uprisings and killings and I knew about the conflicts, but those were nothing compared to when I heard, what seemed to me, Mustafa’s voice, speaking about how he died with many others when a missile struck a peaceful rally and that his girlfriend came and saw him in pieces and that he wanted to say that he loves her, but he no longer could.

I am not a very emotional person and I did not cry then, but when I was writing the letter to Mustafa, I thought that he probably could see me write the letter or something. Later, I went to Tell Me What I Can Do and that is when I almost cried when I saw so many letters full of hope and prayers and support for all the martyrs.

Gardens Speak, possibly the best live artwork I have seen, was a phenomenal experience. From my perspective, it is an extraordinary piece of art, it has the ability to bring people from different parts of the world, with different beliefs, religions, and races, together because nothing motivates love more than the sense of unfair loss. When we, the audience, write letters to the martyr, we all get bound by the same affection.