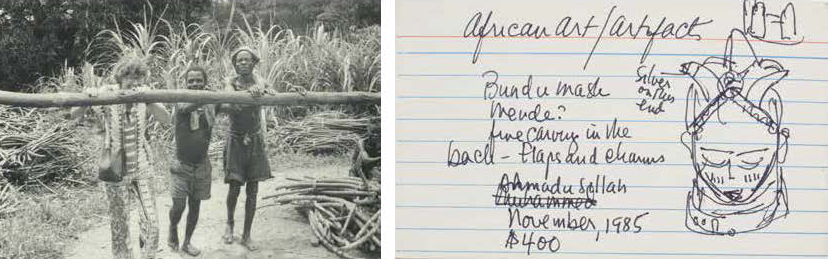

For almost a year, we in Special Collections have been working on a statement documenting the ways in which we are trying to confront the legacies of colonialism and racism in our collections. In June 2020, Black students at Bryn Mawr and Haverford composed an open letter to the Bi-College community. Their letter, which demanded that Bryn Mawr Special Collections acknowledge the colonial racism present in Bryn Mawr’s African Collections and, where possible, create a plan to repatriate objects, represents ongoing, student-led anti-racism efforts at the College—efforts that came to the fore again with the Student Strike in fall 2020. The effects of colonialism and racism in the collections are part of the historical and present-day forms of racism and inequity at Bryn Mawr College that we are committed to addressing, foregrounding, and remediating in the department and at the College as a whole. In response to student voices, the concerns of the wider college community and society, and our own professional ethics, we began working on this statement.

Tied to College and LITS-wide efforts towards diversity, equity, inclusion, and anti-racism, our statement, Confronting the Legacies of Colonialism and Racism in Special Collections, is meant to serve as a starting point for conversation. It is by no means complete or final, and we plan to continue to modify the document as we identify additional ways in which we can address racism and colonialism in Special Collections. As we’ve worked on the statement, we have shared it with some internal stakeholders—the LITS Equity, Inclusion, and Anti-Racism Team, the BMC Collections Committee (which includes faculty and trustees), the President’s Diversity Leadership Group, BMC Alumnae/i Relations and Development, and members of the Bryn Mawr administration. We hope to create a space that allows for on-going discussion, including hosting community-wide conversations about the document in the coming year.

In the meantime, Special Collections staff are engaged in work aimed at addressing the on-going effects of racism and colonialism in our collections, and at increasing the transparency around them. This is a multi-part, long-term project. In addition to addressing our current collection and how we are presenting the material we currently have to the community, we also need to think about future collections. This means identifying and redressing harmful language in descriptions and metadata, actively and ethically acquiring material from a diverse range of voices, and recognizing that we have a professional and ethical obligation to do this work. Special Collections, comprised at Bryn Mawr of Rare Books & Manuscripts, Art & Artifacts, and the College Archives, is primarily intended to be a teaching collection. As educators and caretakers of these collections, we have a responsibility to continue to learn and grow, and we welcome interrogation, critique, and insight into how we can improve our practice.

Read the statement: Confronting the Legacies of Colonialism and Racism in Special Collections

Current, concrete efforts towards this work include:

- Who Built Bryn Mawr? Exhibit and Internships

- Support for the Perry House Oral Histories Project

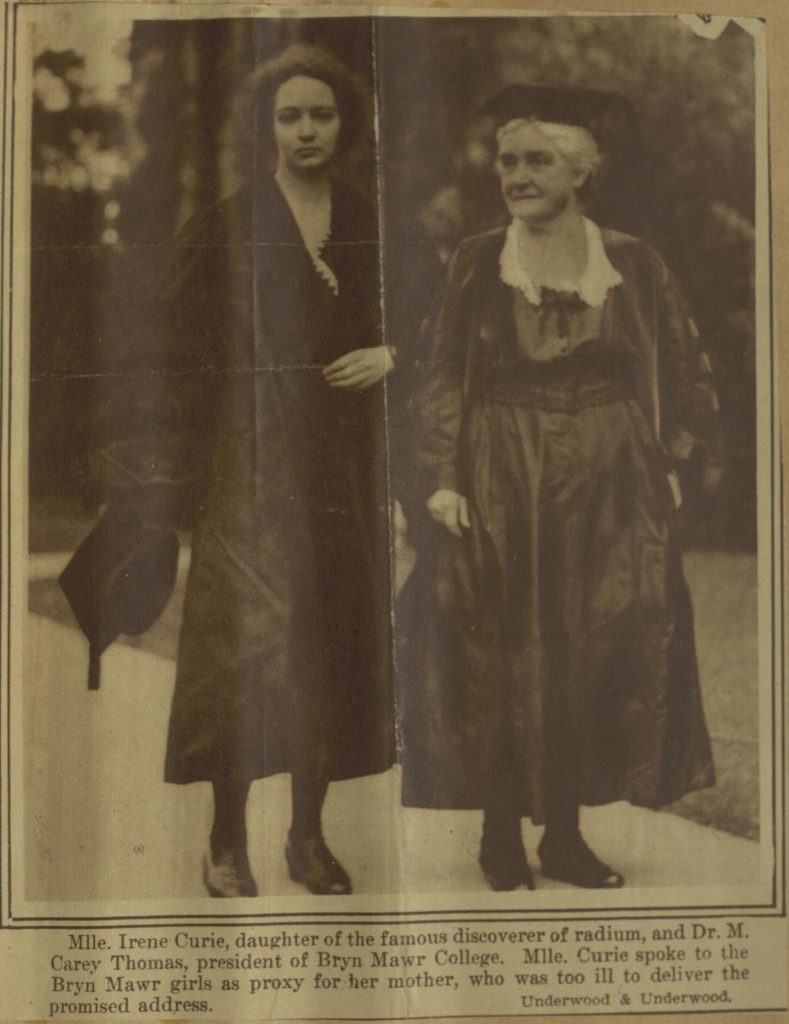

- Removing portraits of M. Carey Thomas from display

- Collecting, preserving, and providing access to materials related to the 2020 Bryn Mawr Strike via the TriCollege Libraries Digital Collections website.

- Supporting and preserving Pensby Fellows research

- Working with the Anthropology and Archaeology Departments to inventory all cultural objects and any human remains stored in campus collections and will continue to adhere to best practices by implementing the legal guidelines put forth by NAGPRA and by adhering to the most recent code of ethics put forth by professional organizations such as the American Anthropological Association, the American Association of Physical Anthropology, and the Society for American Archaeology

- Ongoing improvements of catalog records for African Art & Cultural Artifacts, including identification and provenance research, donor biography research, and development of 2021 summer internship focused on integrating these collections with relevant papers in College Archives

- Ongoing development of resources page for researching African Material Culture, including timeline draft of Art & Artifacts collection history

- Developing websites to document previous exhibitions on campus, including Exhibiting Africa (2017)

- Auditing archival finding aids and digital collections description to bring description up to standards as laid out in the Archives for Black Lives in Philadelphia Anti-Racist Description Resources

- Identifying books with problematic themes, language, and/or art through use of subject headings and genre terms such as Racism in literature, Ethnic stereotypes, etc.

- Updating and improving the cataloging of historic books to illuminate unexamined facets of contemporary society

- Hosting Teach-In on Legacies of Colonialism in the Mineral Collection (with Selby Hearth and Ellie Ga)

- Hosting Teach-In on Race, Racism & Cultural Collections (Monique Scott with Tessa Haas)

- New acquisitions of contemporary artwork by African American Women

- Deepening representation of work by Kris Graves in Art & Artifacts collection to include his most recent portfolio of photographs from protests in Richmond, VA (Summer 2020)

- Outreach and connecting with stakeholders and cultural representatives