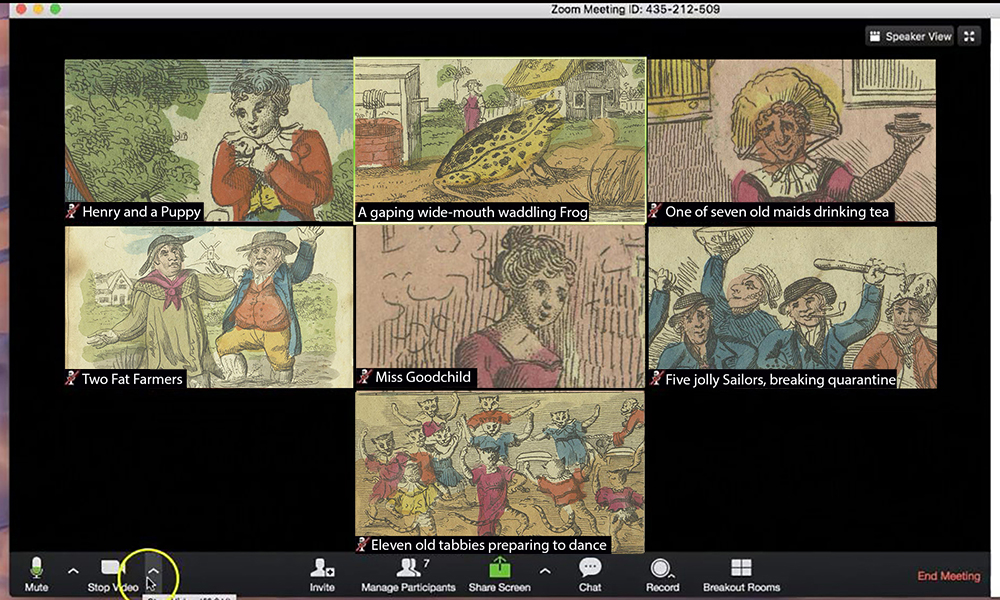

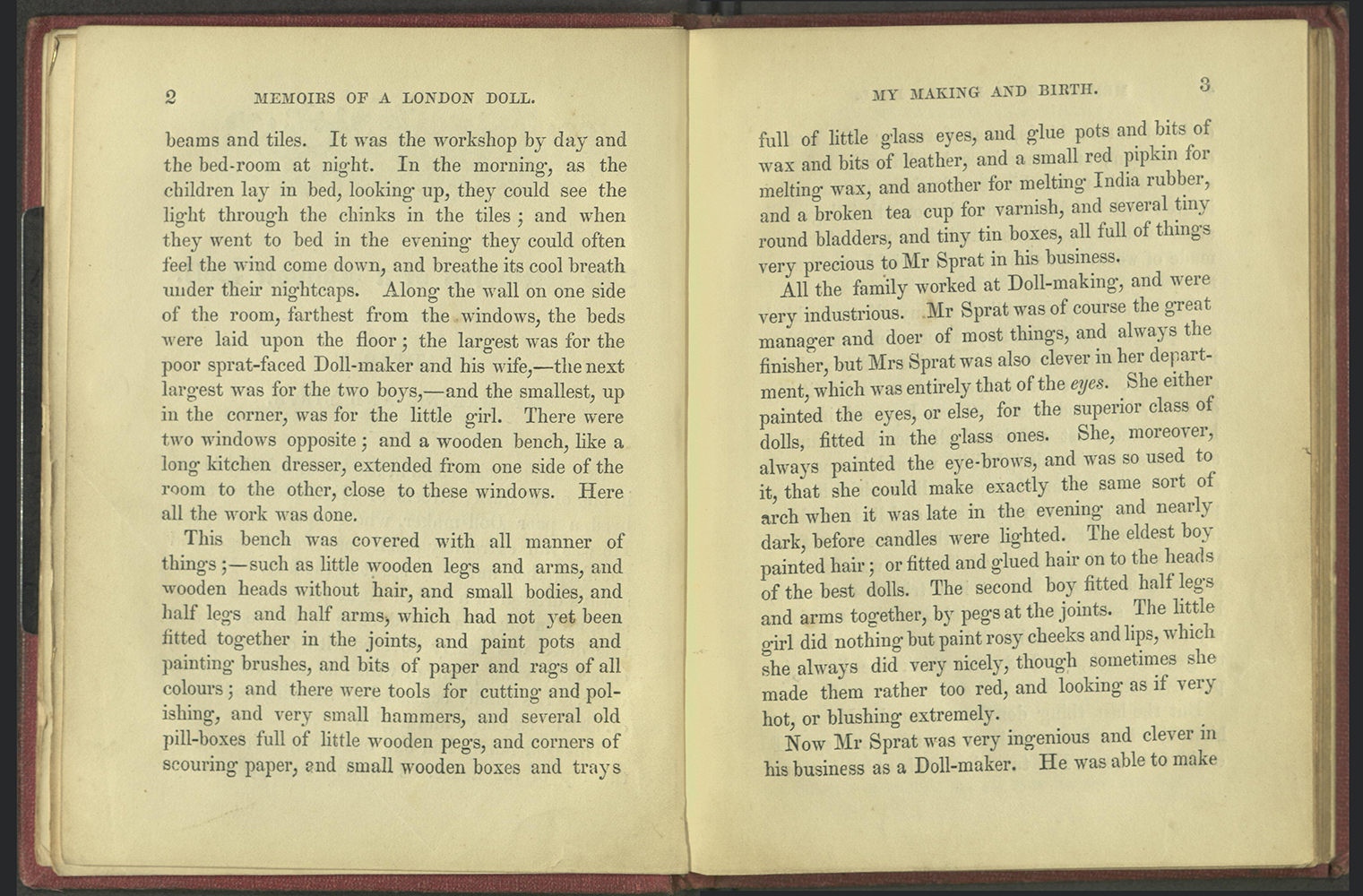

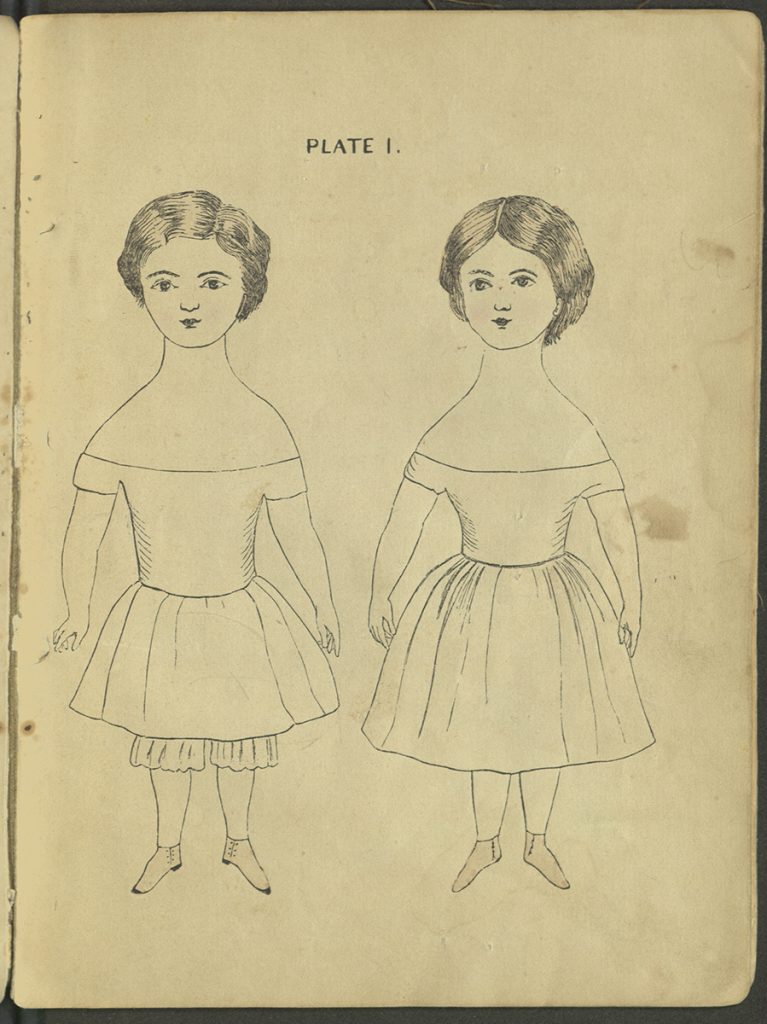

The London doll whose story is recorded in this book comes to consciousness in the home of a skillful but poorly remunerated maker of joined wooden dolls, Mr. Sprat. He, his wife, and their three children live in a rented top floor room, “the workshop by day and the bed-room at night.” The work benches are along the side of the room with windows, the beds on the floor on the opposite wall. Mr. Sprat makes the wooden parts for the dolls. Mrs. Sprat paints the eyebrows and eyes or, in the case of more expensive dolls, inserts glass eyes. The two boys paint hair or attach wigs, and fit the arms and legs together with pegs, respectively. The little girl paints the blushing cheeks and sweet lips. This industrious family produces dolls in bulk, and one day Mrs. Sprat puts the heroine of this story in a basket with nine other dolls, each wrapped in silver paper and carries them to a doll shop in High Holborn.

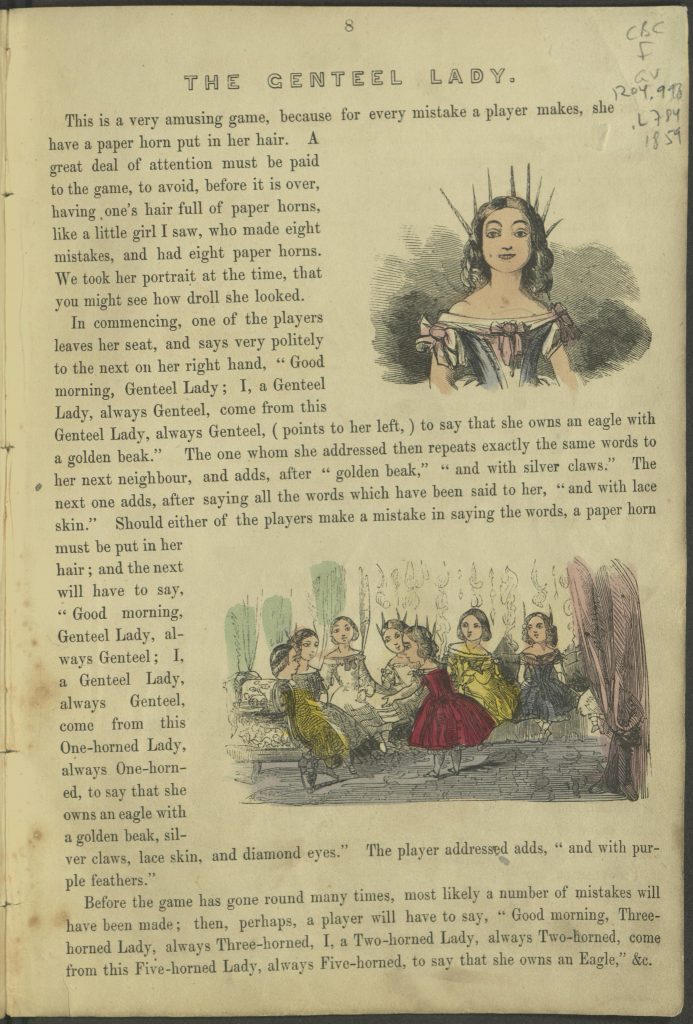

Although the doll longs to be put in the front window, she is stored on a high shelf for some time – “it seemed like years to me” – in the back parlour where she has nothing to do but listen to the daughter of the owner read aloud popular children’s books. One day, though, a boy arrives, asking to trade a fruit cake made for the Twelfth Night celebrations for a doll for his sister. He and the doll shop owner exchange increasingly laudatory descriptions of the objects they are negotiating over; the owner claims the doll, “of a very superior make,” is worth twelve shillings, to which the boy responds that the going price for the cake in the shop of his grandfather, a pastry-cook, is fifteen shillings or more.

In the end, the boy gets the doll for his sister, Ellen, and they return to the pastry-cooks’ house, where the old man asks the child to put the doll away, because he needs her to join in the work for the holiday: “to sort small cakes, and mix sugar plums of different colours, and pile up sticks of barley sugar, and arrange artificial flowers, and stick bits of holly with red berries into cakes for the upper shelves of his shop window.” When Ellen finally brings her new toy down, the doll is astonished by what she drolly describes, in a foreshadowing of a recent catchphrase, as “the fine front shop with All the Cakes!” Overcome by the beauty of the decorations, she faints.

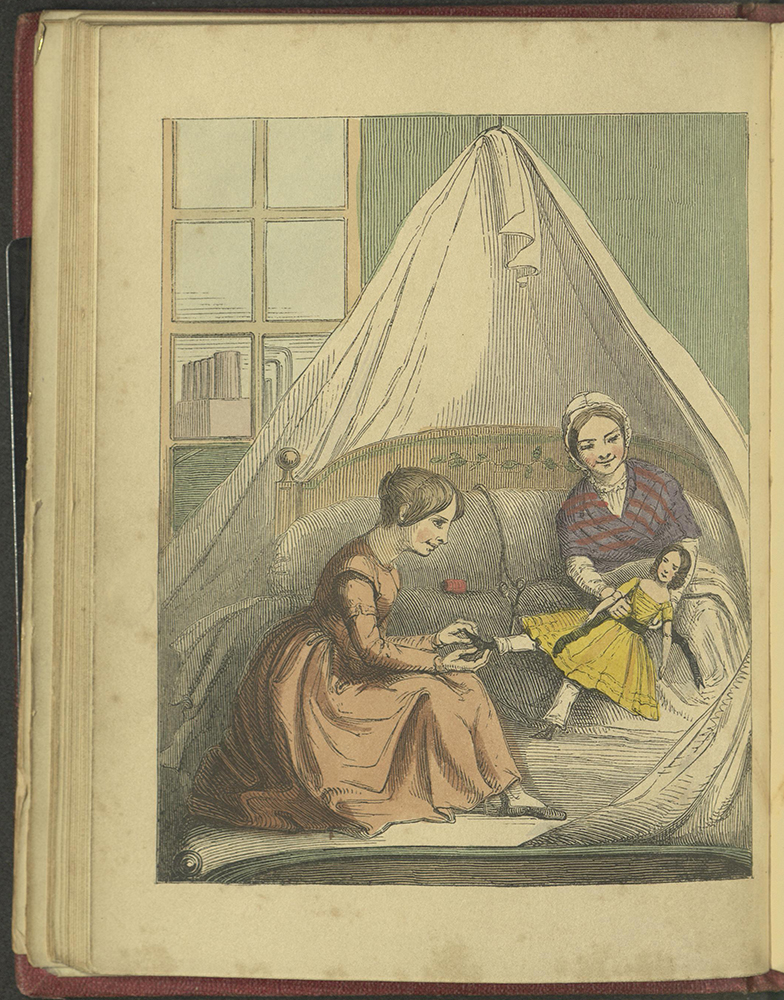

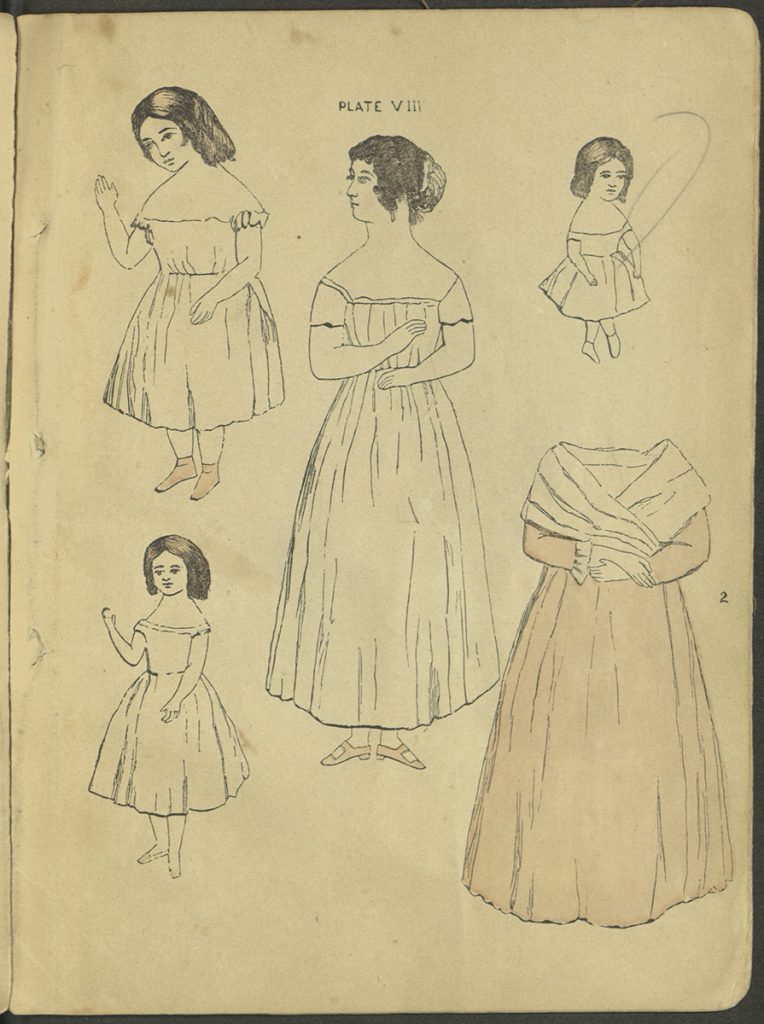

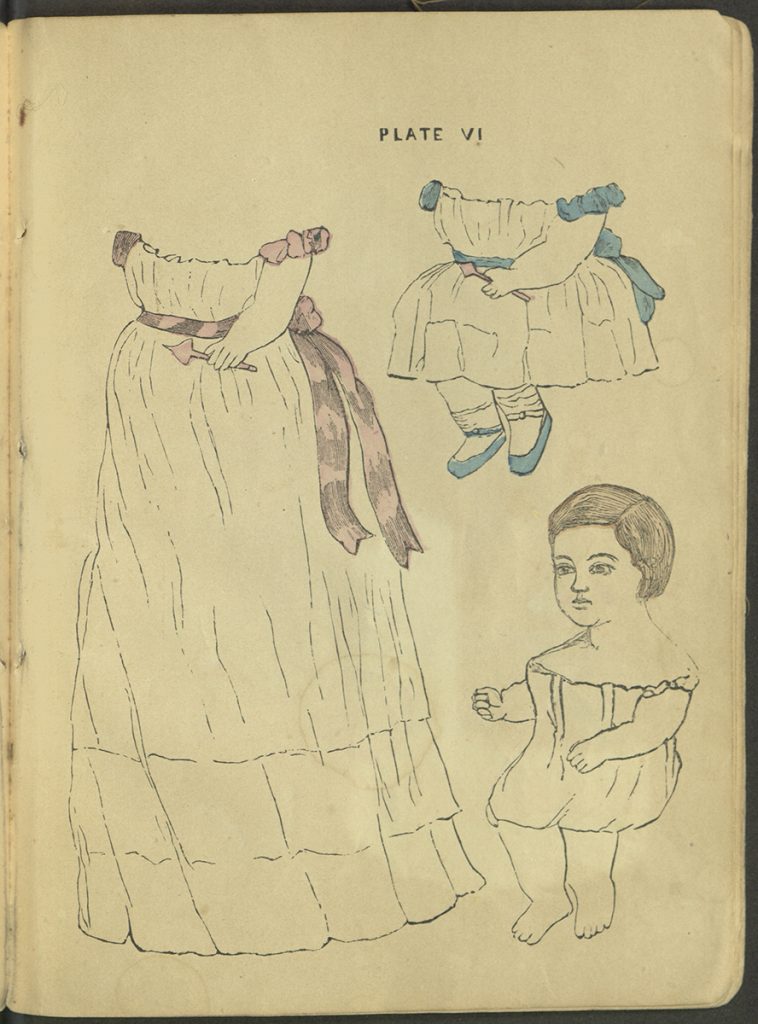

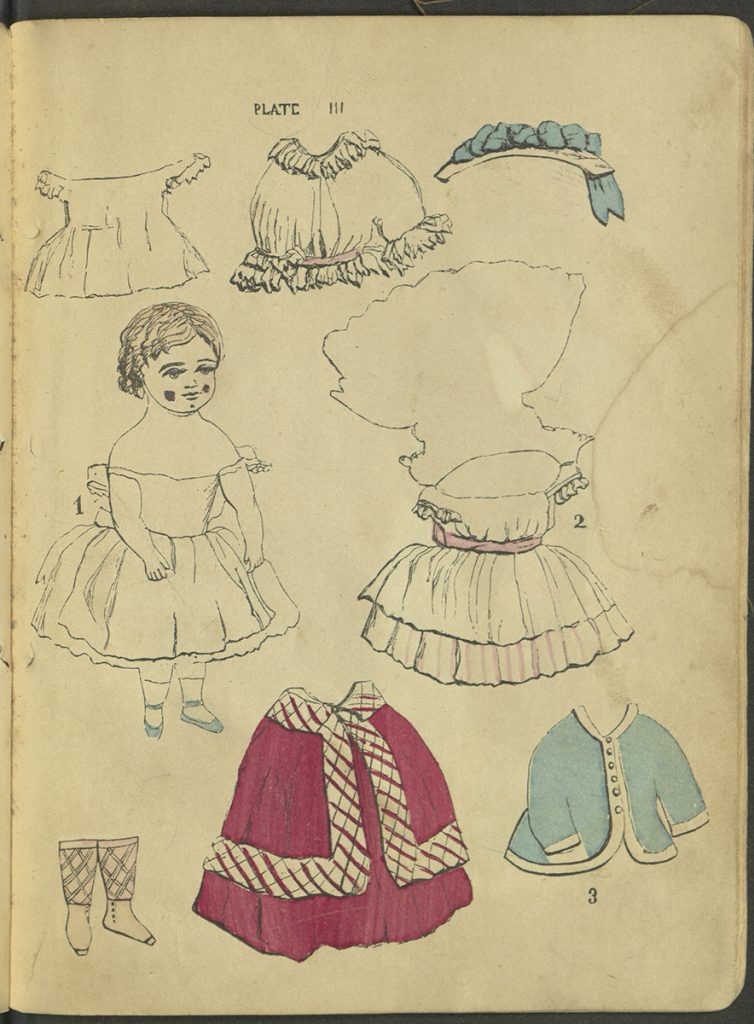

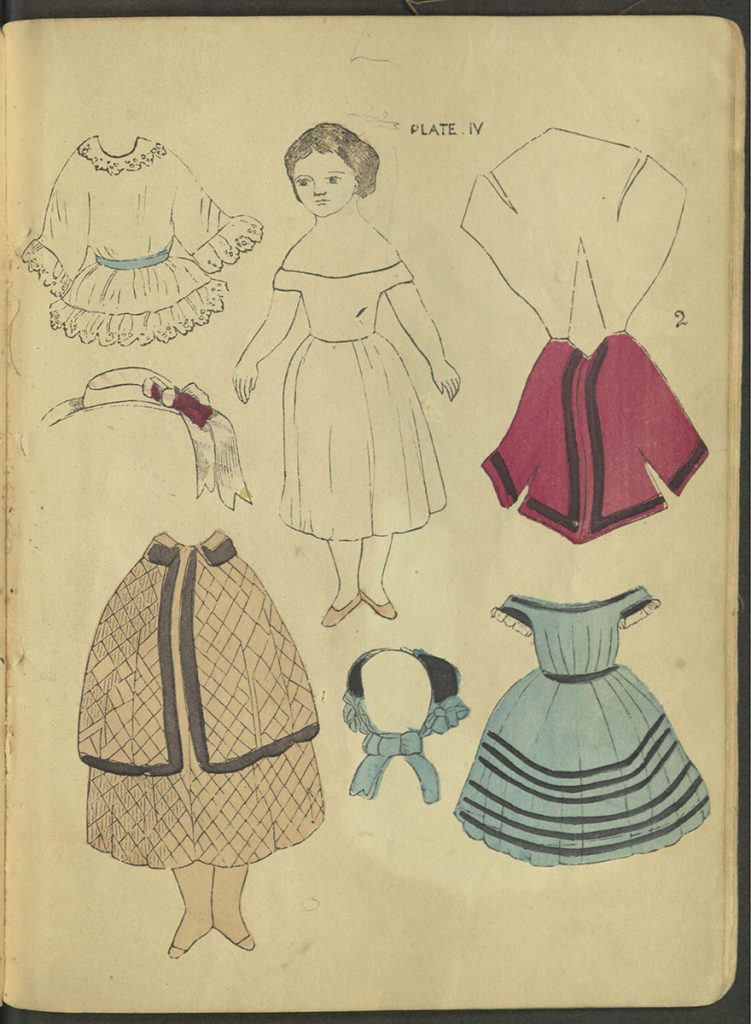

The doll is happy at the pastrycook’s, but her seven-year-old “mamma” is soon sent to live with her aunt, a dressmaker. Aunt Sharpshins employs fifteen apprentices, of whom the next youngest is ten. They work from six in the morning until eight at night, with a half hour lunch break, and are exhausted and poorly fed. Under this regime, Ellen becomes ill, and she and her friend Nanny take advantage of her two sick days to finally make clothing for the doll, now christened Maria Poppet.

The story is too long to recount event by event, but by now it must be clear that the author has little interest in the sort of minor domestic incident one expects in stories about dolls, and a great deal of interest in the economic and employment situations in which children in London were living. In fact, Richard Horne’s book was first published in in 1846, three years after he finished his work as a member of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Children’s Employment. The Commission interviewed children in factories, mines, and smaller industries and businesses, investigating their work conditions, their access to education, and their diet.The report was greeted by public outrage, and inspired poets and writers including Charles Dickens to write about children who were obliged to work to survive. Horne’s Memoirs of a London Doll reflects what he learned as a member of the Commission, and reshapes the Report of the Commission into a palatable message for young readers about the hardships endured by children less affluent and less fortunate than themselves.

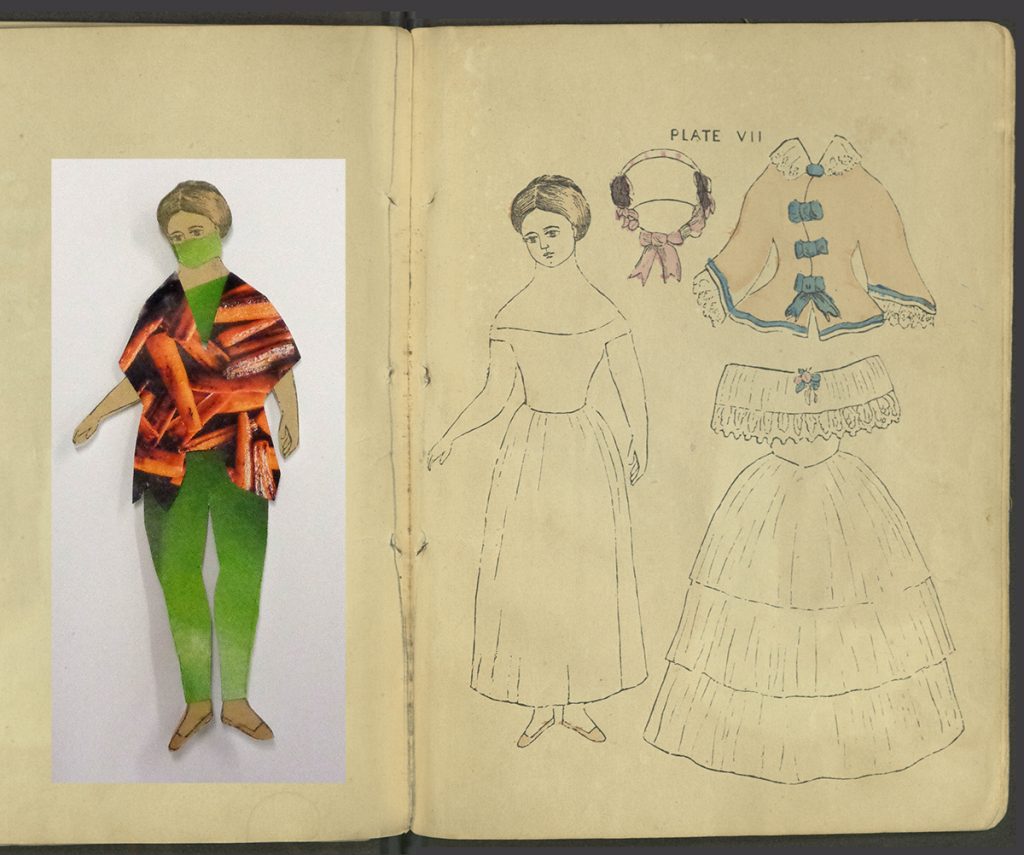

Horne was a friend of Dickens, and was employed by him as a sub-editor at the weekly magazine Household Words. The two men were part of a network of journalists, scholars, and philanthropists interested in understanding and improving the lives of the poor. Among the most interesting of these, from the standpoint of this book, was Margaret Gillies, a professional painter working primarily in watercolors and miniatures, who illustrated the story. She and her sister, the author Mary Gillies, resided in London and by 1841, they had been joined by the physician and sanitary reformer Southwood Smith (who lived with Margaret for the rest of his life). Among his other work, Smith examined and reported on the lives of child workers in the mines – boys and girls, who often started before they were ten, and whose work included opening and closing ventilation doors, running errands, and dragging loads of coal through tunnels too small for ponies to work in. In 1842, Gillies illustrated Smith’s first report, on his inspections in Leicestershire and West Yorkshire.

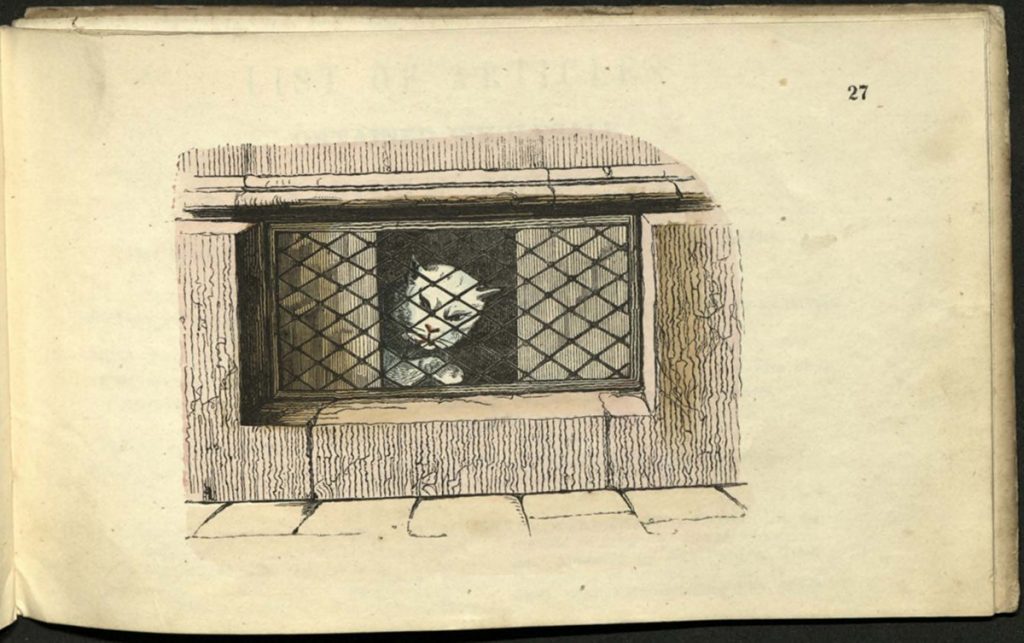

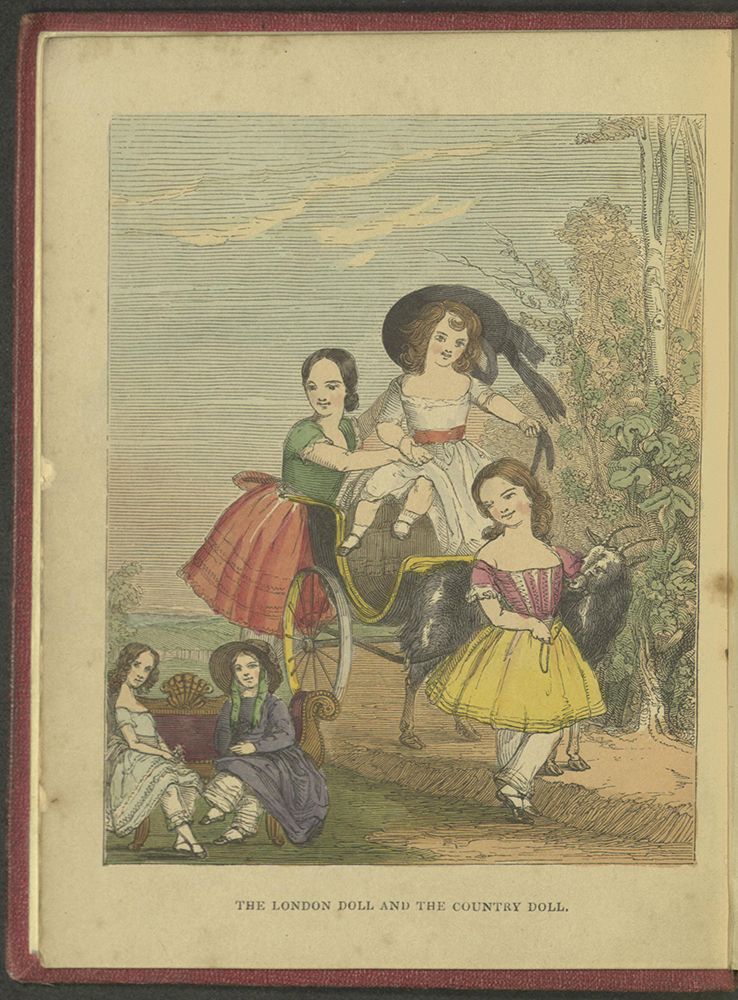

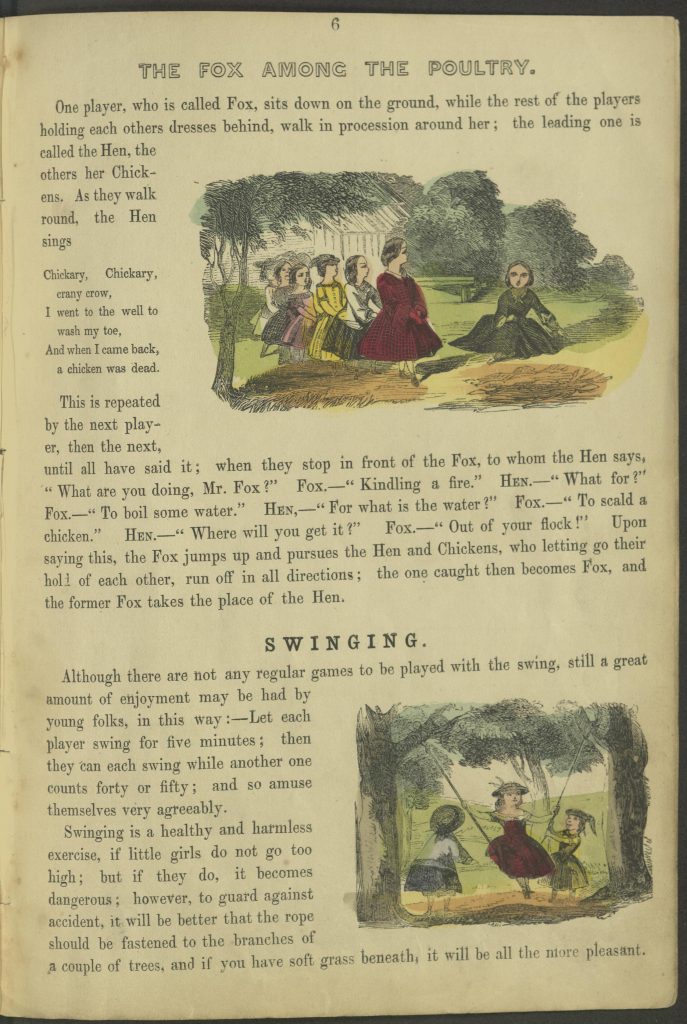

True to his interests, Horne led Maria Poppet through a rapid succession of adventures with “mammas” in different walks of life. After Ellen, she passes into the home of the spoiled and heedless Lady Flora, the daughter of a countess and a cabinet minister. Maria lives in luxury with a doll bed complete with mattress and her own dresser for an expanding wardrobe, enjoys shopping, goes to the zoo, and attends the Opera. A dangerous accident sends her to a different home.

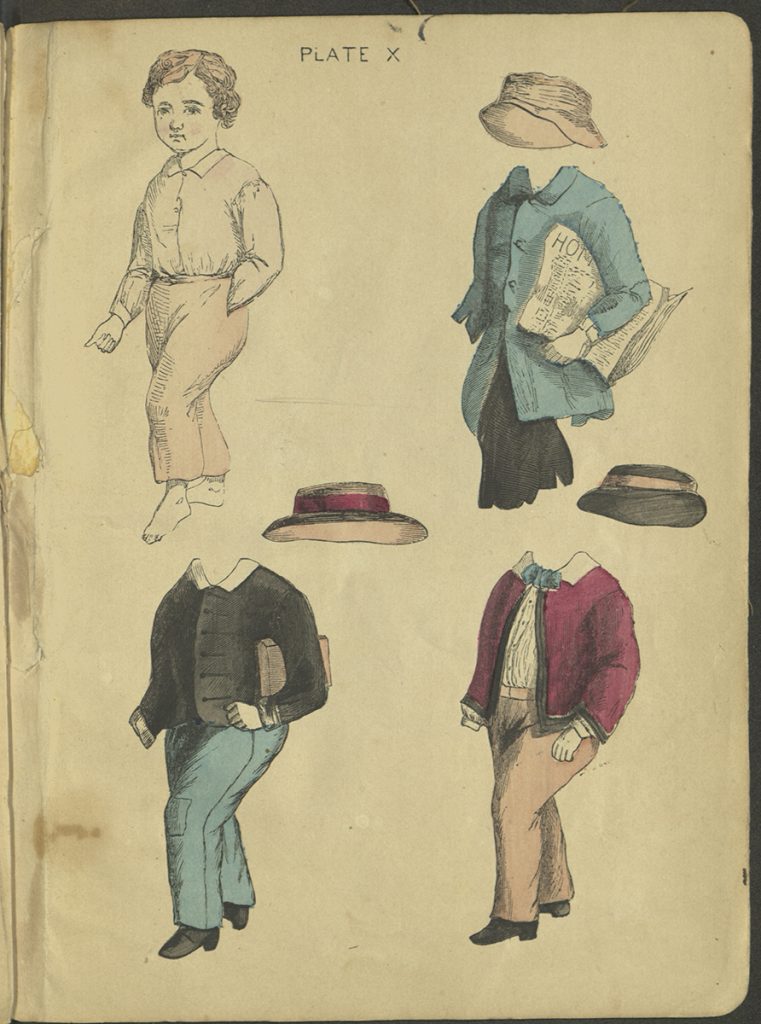

She lives briefly with Mary Hope, staying with her aunt because her father, who is a clerk in a bank, has “seven other daughters, and a small salary.” Mary drops her accidentally from a coach while watching a Punch and Judy show, and the doll is inadvertently exchanged for Punch’s baby. The master of the show sells her to a street merchant who deals in used clothing. He sells her to a young Italian organ-grinder who scrapes a living for himself and his sister. The little girl plays with her as she would any doll, but business is business and the two performers also dress her in their (deceased) monkey’s clothing and prop her up on top of the barrel organ. After several additional changes in status and position, Maria Poppet finally ends up at the country manor of a wealthy family, where she believes she has come to rest. She tells us that she has made the acquaintance of another doll whose life story she has heard, and that she hopes “at a future time that these ‘Memoirs of a Country Doll’ will be made public as mine have been.”

Horne never did write that sequel, and one doubts the ingenious journalist could have described the exhausting and grim lives of young rural workers and child miners in a sufficiently softened and light-hearted way for his juvenile audience. At the same time, it would have been a very interesting book. The Memoirs of a London Doll is quick-paced and full of fascinating detail. The reader who is not ready to plunge into the thousands of pages of Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor (published in 1851 by another member of Dickens’ coterie) could start here to ease into the harsh realities of the mid-19th-century metropolis .

Marianne Hansen, Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts

Horne, R. H. (Richard H.) and Margaret Gillies, illustrator. Memoirs of a London Doll, Written by Herself. London: Henry G. Bohn, York Street, Covent Garden, 1855

Read our copy on the Internet Archive.

With the continuing closure of the Library, we are blogging regularly about books from the exhibition, The Girl’s Own Book. Please follow us on Facebook or subscribe here for notices of new blog posts.

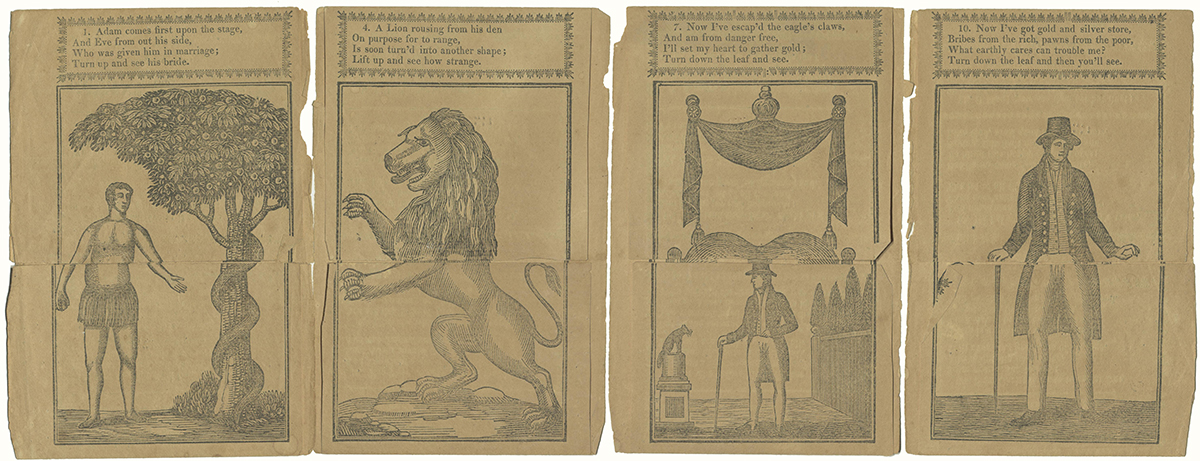

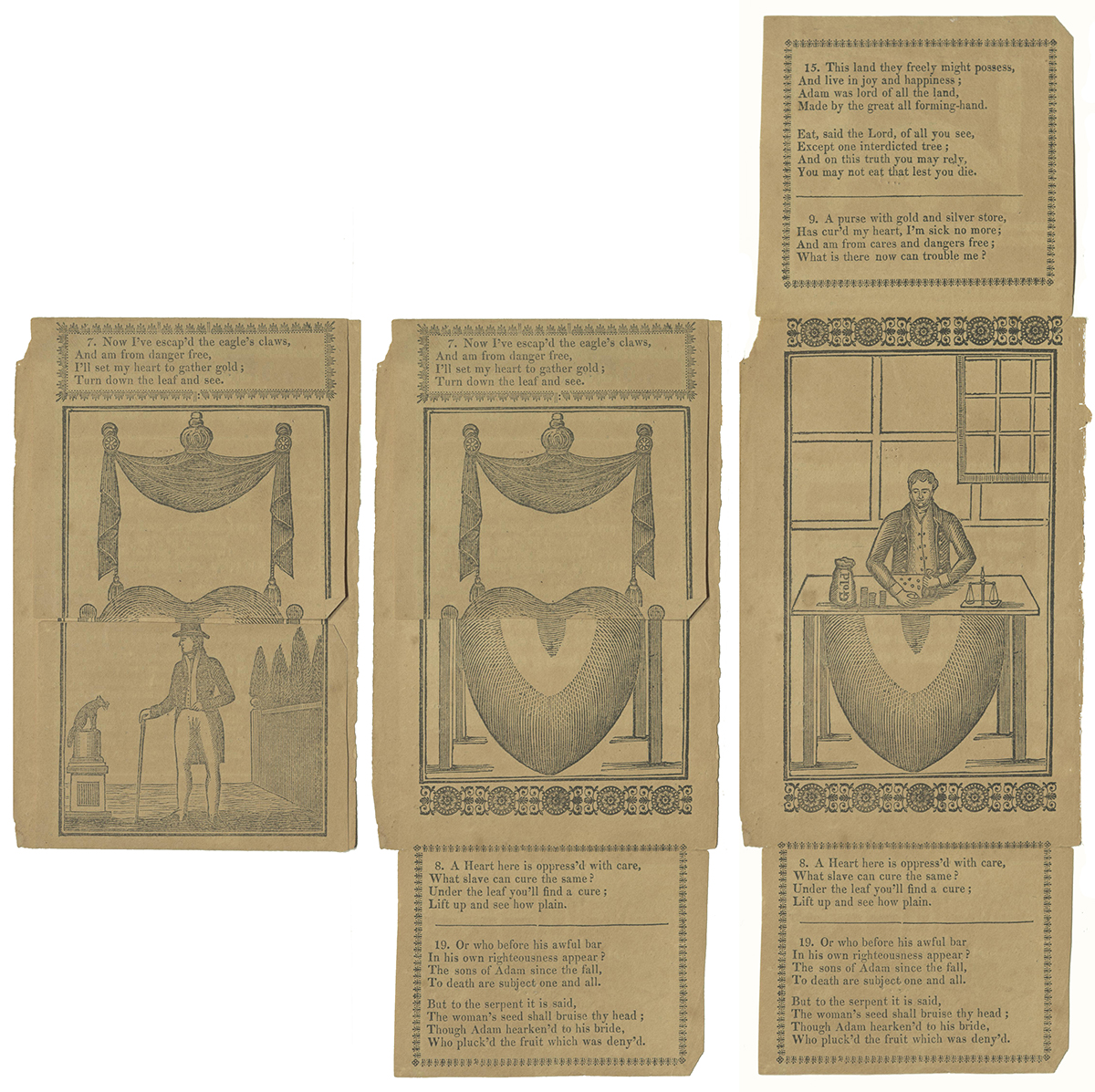

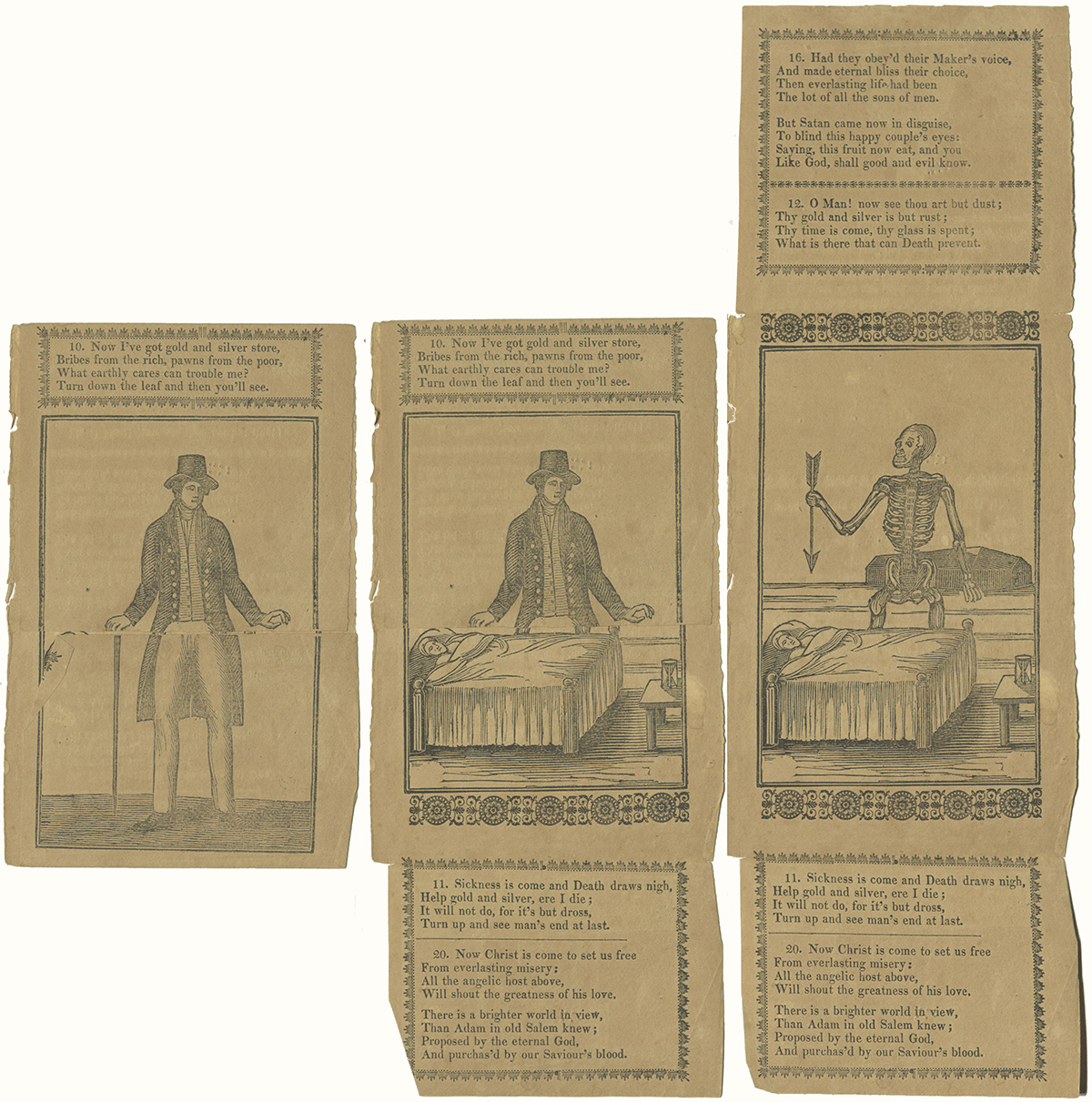

![Verse 13: Adam and Eve in innocence, God was their glory and defence : Had they continued in that state, Their happiness had been complete. Angels, behold the happy pair, Who did your Maker’s image wear, While in obedience they remain’d And their innocence maintained. Verse 14: In happy Eden see them plac’d, Who stood or fell for all our race; In a sweet bower, composed of love, This happy pair might safely rove. There was no curse upon that ground, Nor changing grief there to be found: There nothing could their joys controul [sic], Nor mar the pleasures of the soul. Verse 15: This land they freely might possess, And live in joy and happiness: Adam was lord of all the land, Made by the great all-forming hand. Eat, said the Lord, of all you see, Except one interdicted tree; And on this truth you may rely, You may not eat that lest you die. Verse 16 (not numbered): Had they obey’d their Maker’s voice, And made eternal bliss their choice, Then everlasting life had been The lot of all the sons of men. But Satan came now in disguise, To blind this happy couple’s eyes: Saying, this fruit now eat, and you Like God, shall good and evil know.](http://specialcollections.blogs.brynmawr.edu/files/2020/06/13through16.jpg)