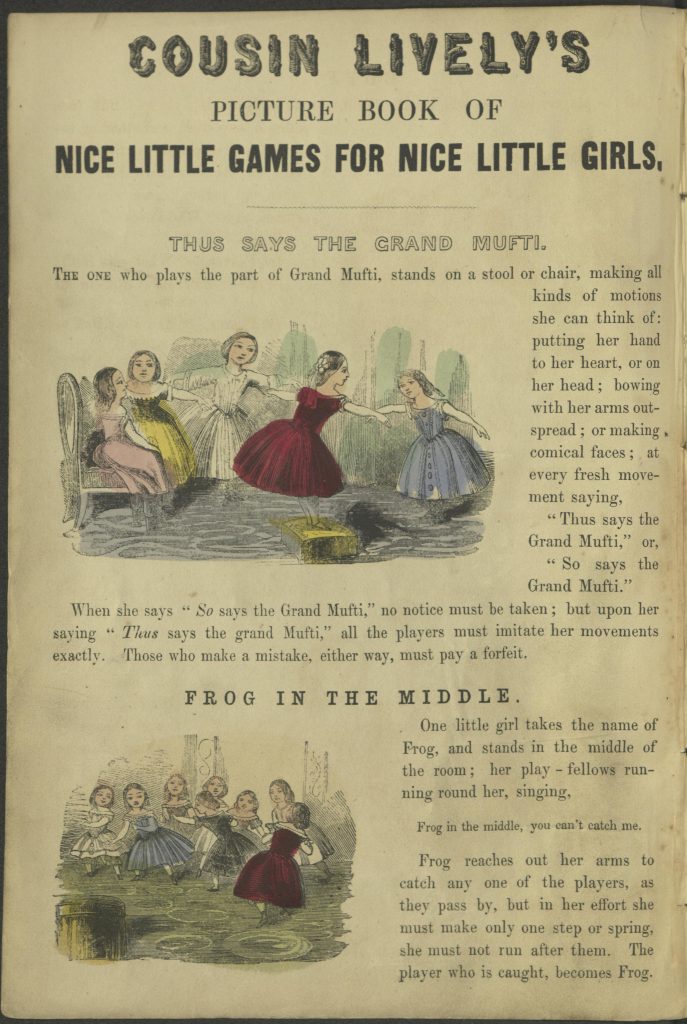

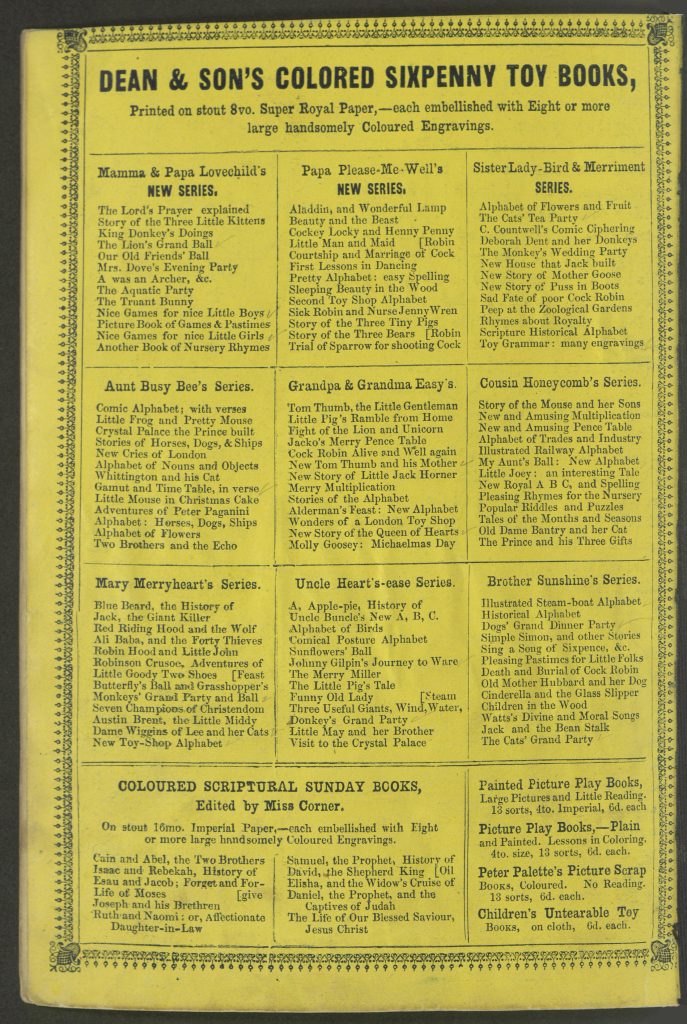

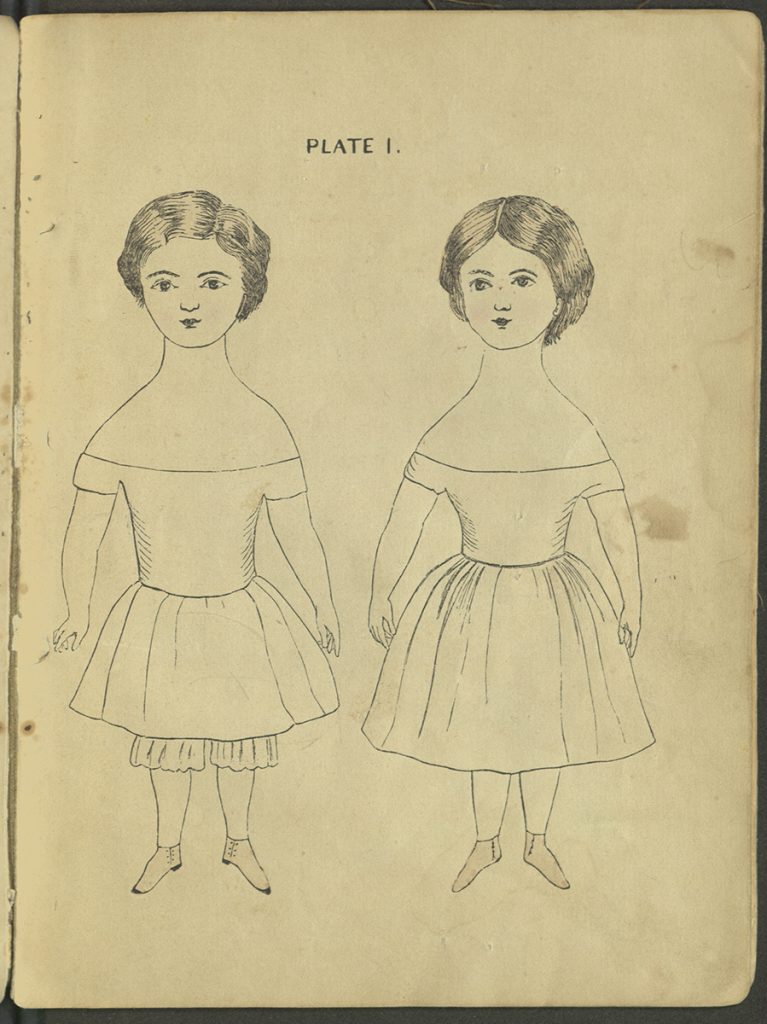

Nice Little Games for Nice Little Girls was one of several volumes of amusements issued by Dean & Sons in the 1850s and 60s. Other books in the Mamma and Papa Lovechild series included Nice Little Games for Nice Little Boys, Picture Book of Games and Pastimes (for older children), and The Pleasing Book of Boy’s Sports. Dean offered many books in series, often named after a “relative” – Sister Lady-Bird, Brother Sunshine, and so on. Our book’s full title begins Cousin Lively’s Picture Book of Nice Little… These rather similar books are differentiated by the gender and age of their prospective audiences. Our book is distinctly meant for girls, and it provides a number of clues for the modern reader about what that meant to the anonymous compiler.

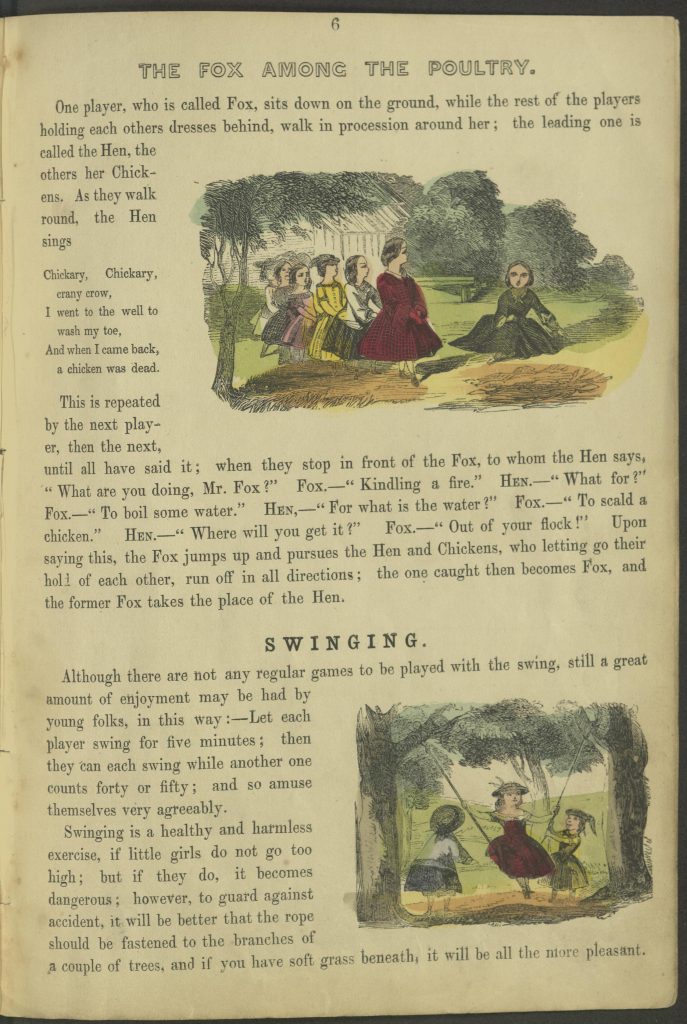

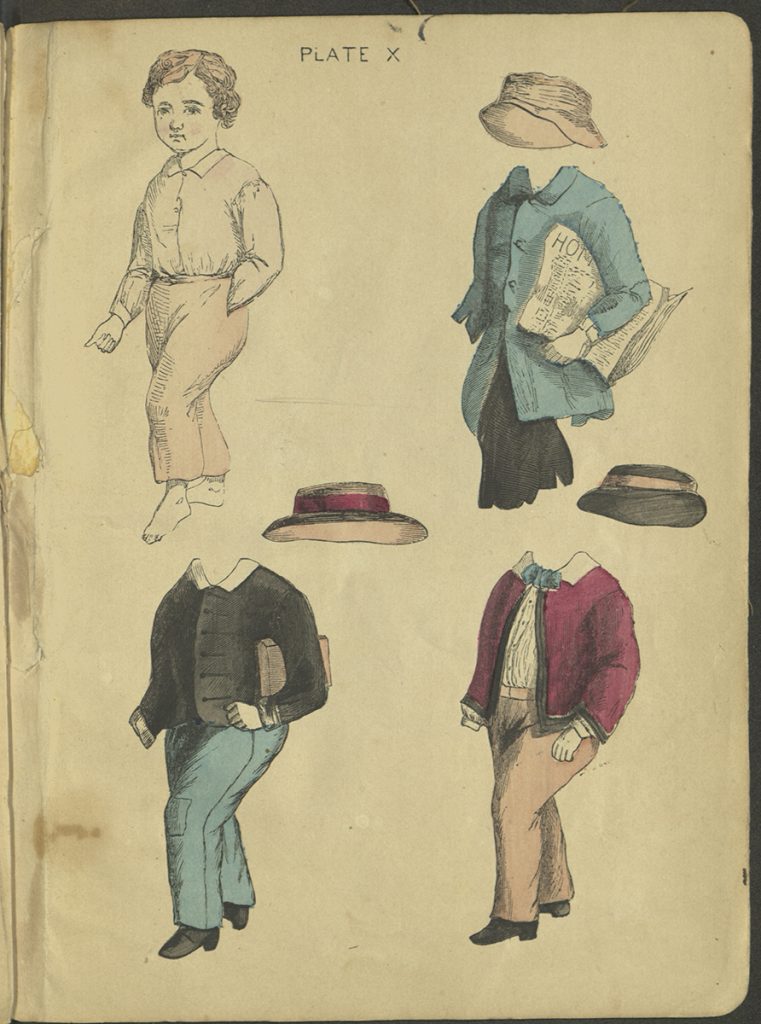

The amusements are meant for very young girls – small enough for the warning that the swing should be tied to two trees, which limits the length of the arc the swing can move through. This age range is confirmed by the book for “little boys,” where the children are shown in skirts, rather than trousers, identifying them as too young to go to school – at most five or, just possibly, six.

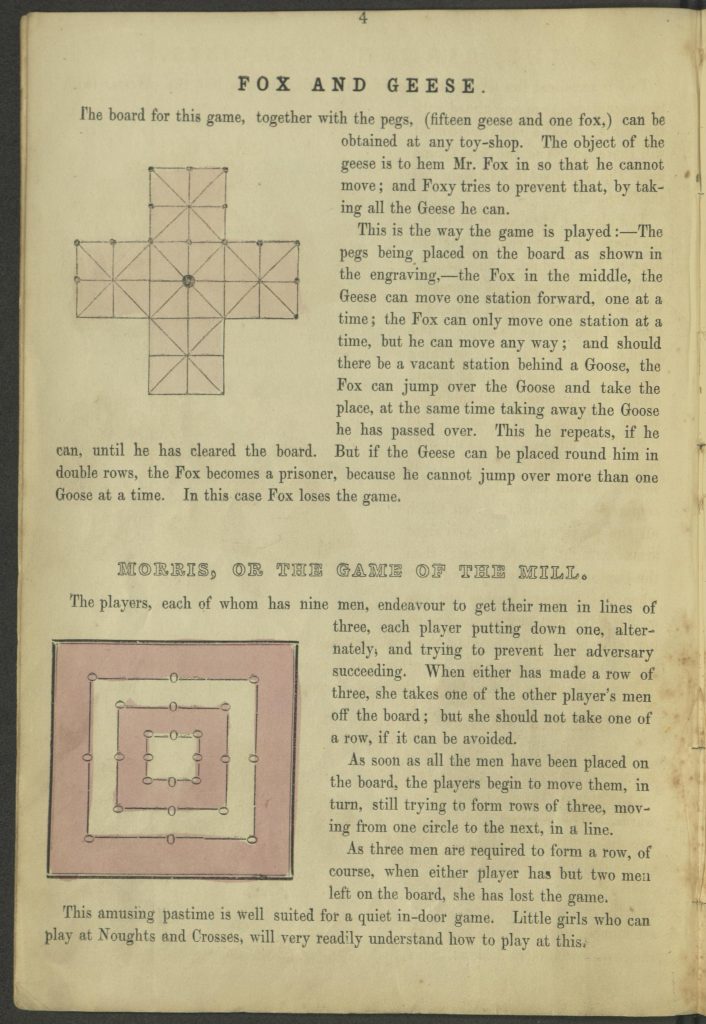

The board games are also chosen for children who probably still need someone to read the book to them. Nine-men’s morris is offered as comprehensible by girls who are able to play tic-tac-toe (around four years old) And the variant of Fox and Geese adds additional geese to the traditional thirteen to make the sides more even.

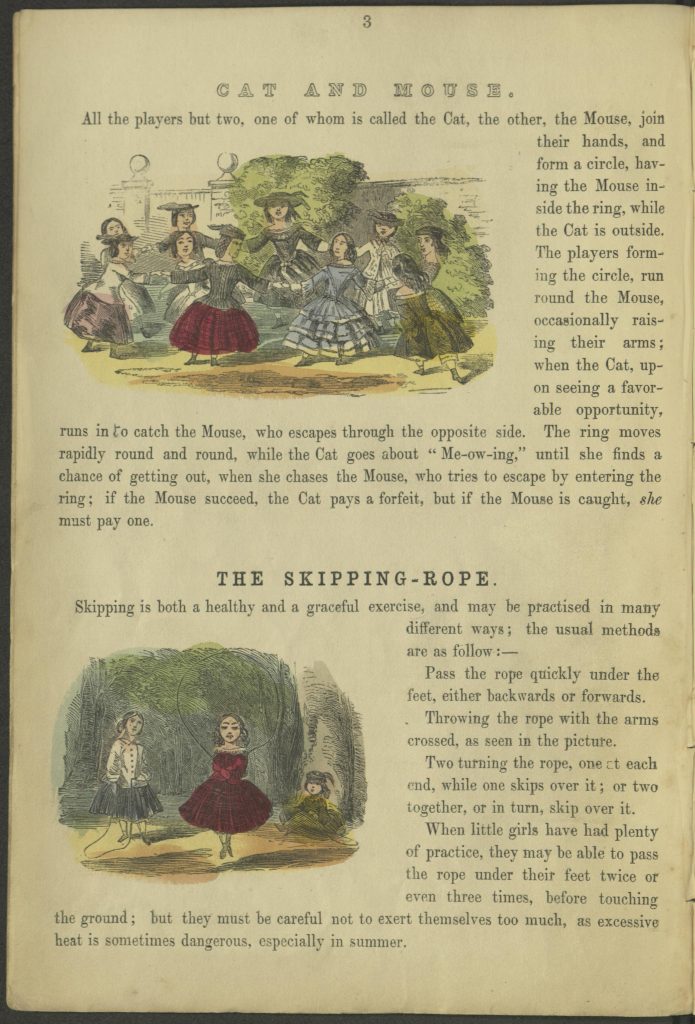

There are many active, primarily outdoor, activities, some competitive, some requiring cooperation. The warning against overexertion while skipping rope reflects ideas about gender and physical activity. But many active games are included, in spite of reservations, and skipping is described as “a healthy and graceful exercise,” revealing more interest in fitness than one might predict of a Victorian writer. The companion book, “Games and Pastimes” includes archery, hopscotch, badminton, a game related to cricket, and other athletic activities as suitable for girls as well.

An important difference between this and its “brother” book is that many of the boys’ games include striking one another or contain other aggressive components; the girls play together without much conflict. The author has to add rules to some of the pleasurable activities suggested to make them “games.” As revealed by “Cup and Ball,” a game has at least two players, a competition, and a winner – or more commonly, a loser.

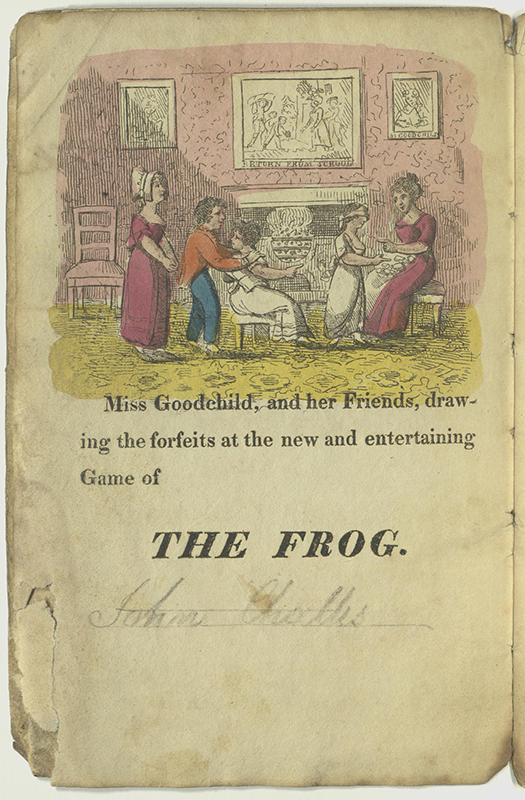

Fortunately, disappointment or triumph is often fleeting: the rounds in many of the games are short, and the loser in any round simply takes over the special role, for example, as the frog in “Frog in the Middle.”

Fortunately, disappointment or triumph is often fleeting: the rounds in many of the games are short, and the loser in any round simply takes over the special role, for example, as the frog in “Frog in the Middle.”

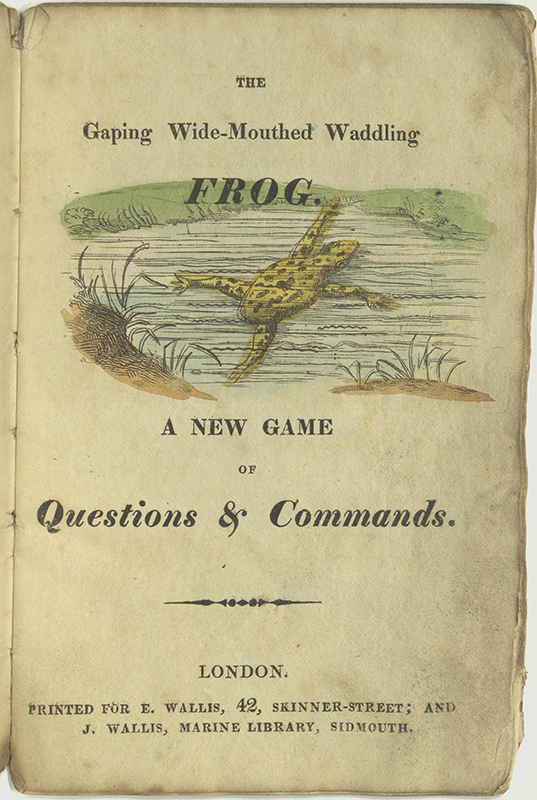

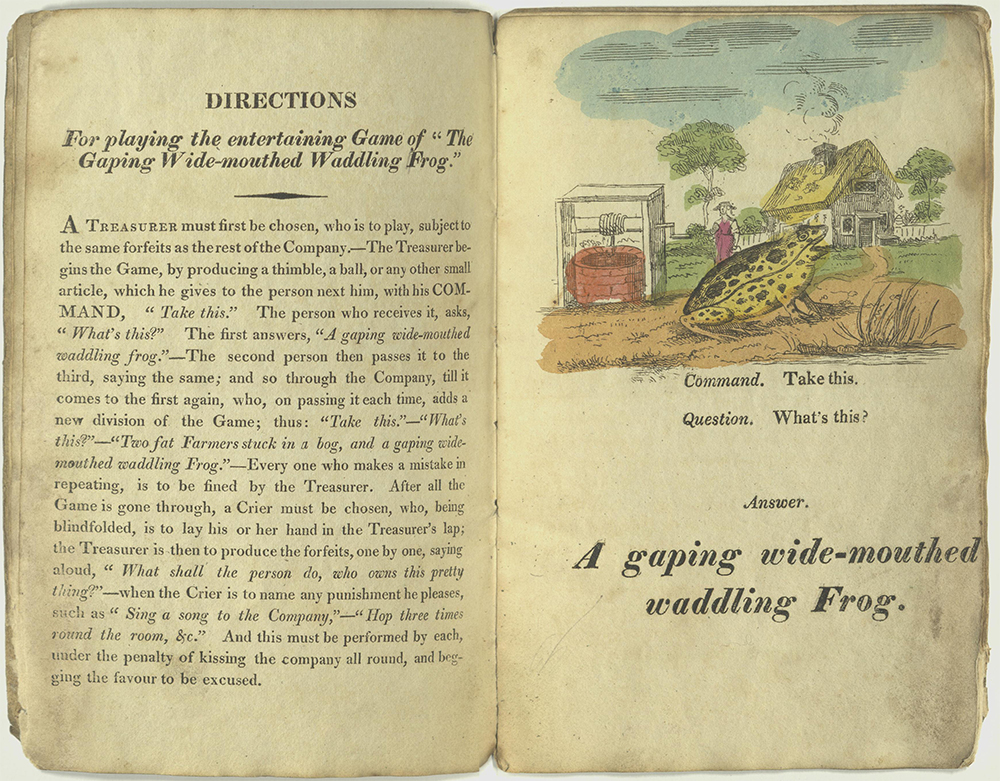

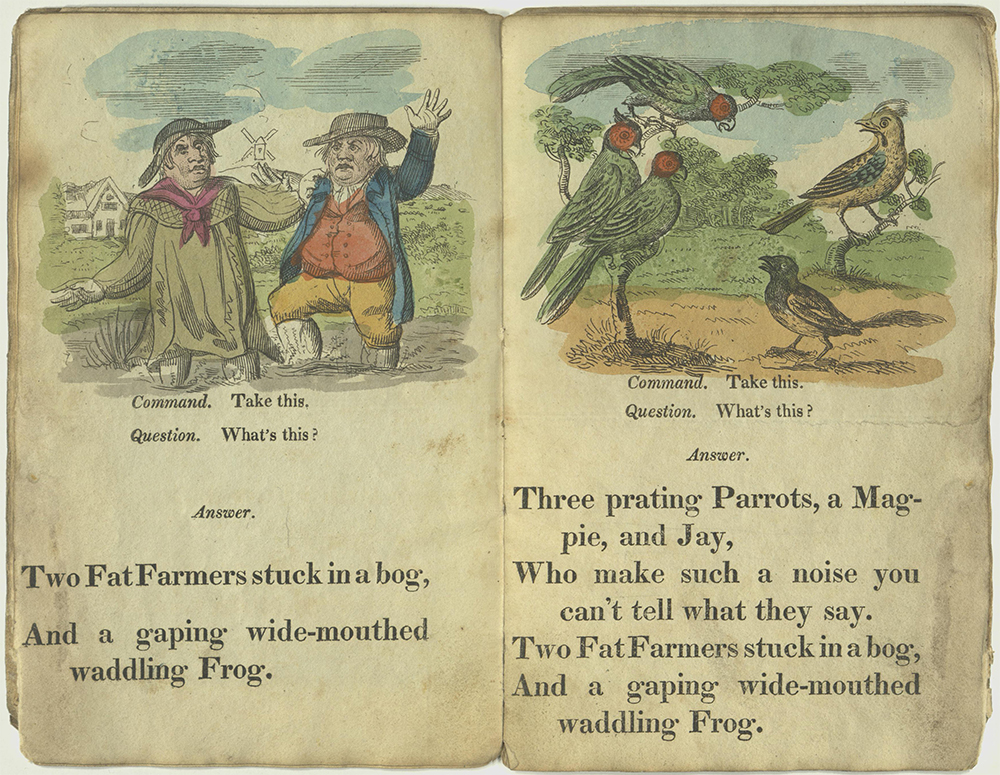

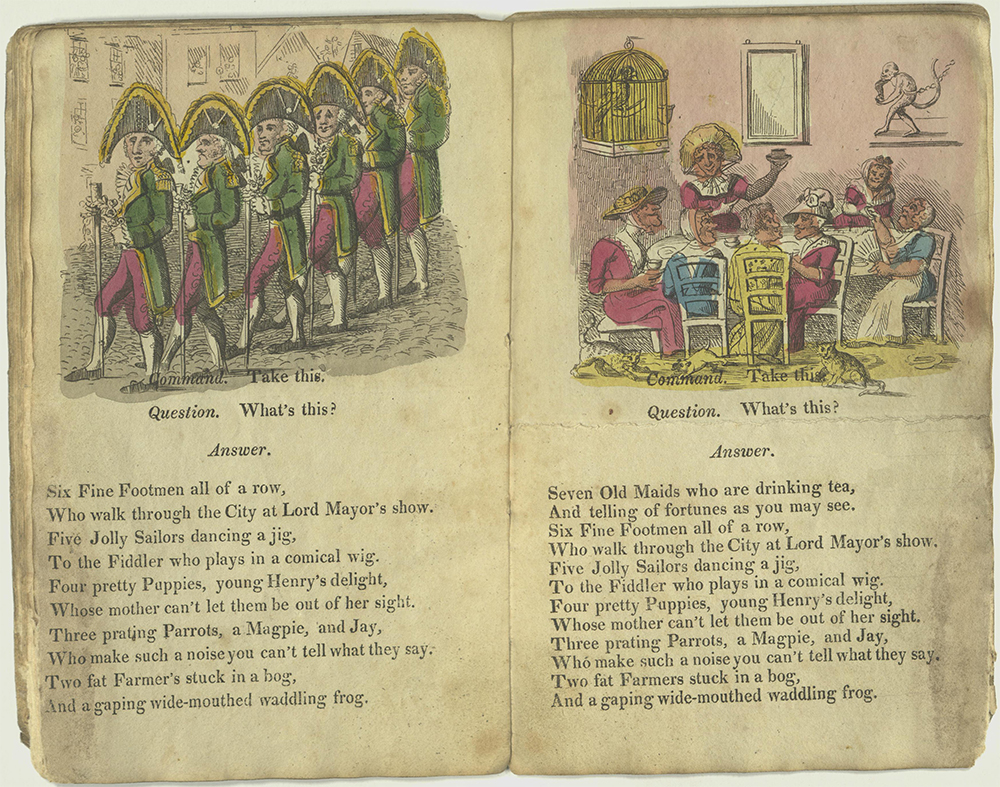

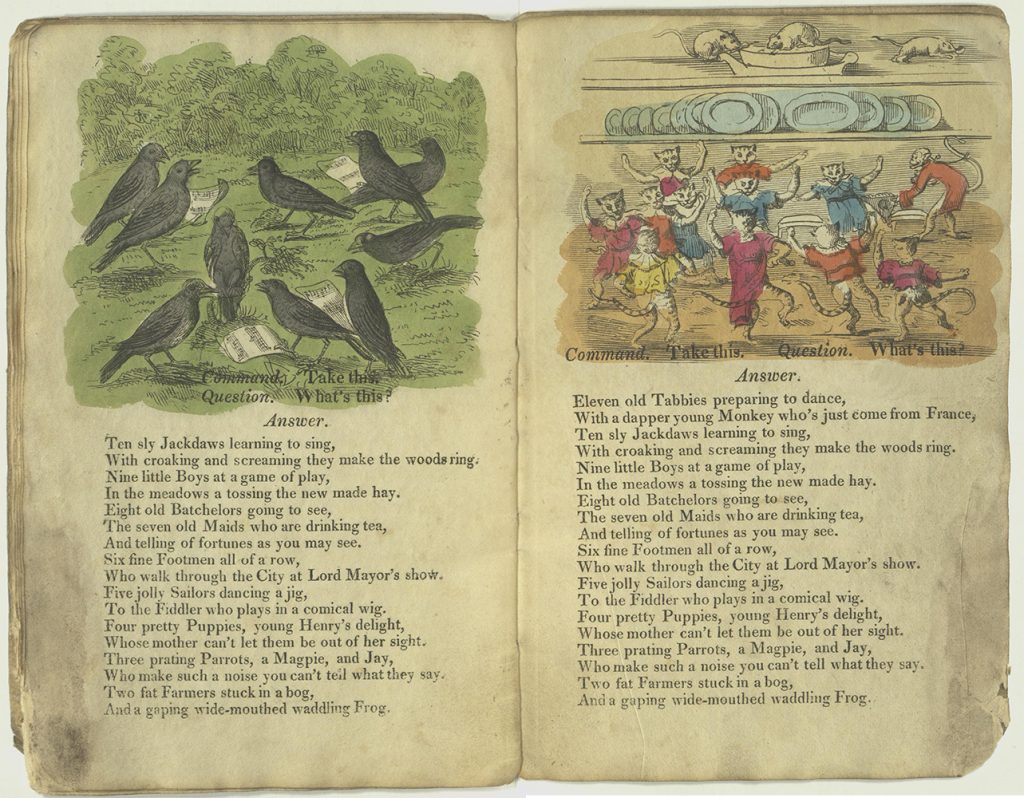

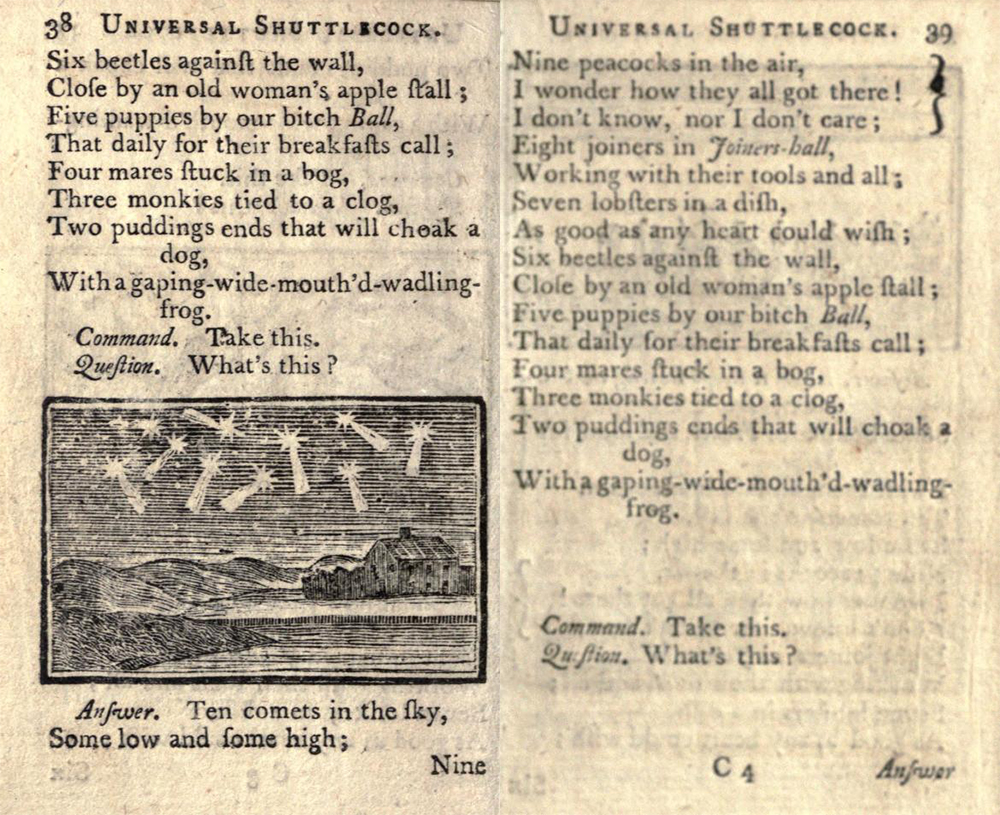

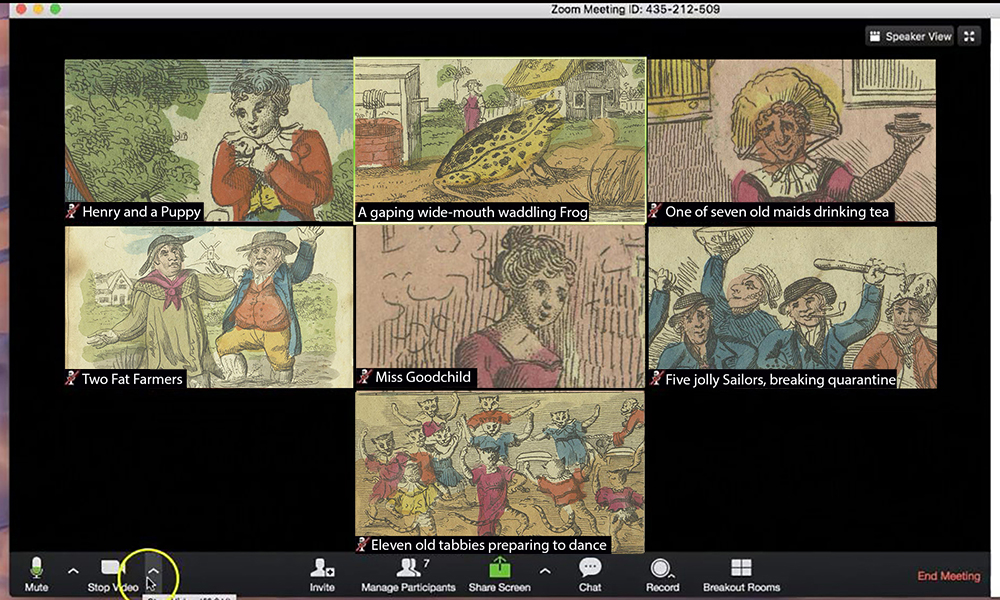

Games which depend on quick thinking are more likely to have multiple losers, and the forfeits we discussed when we looked at the Wide-Mouthed Waddling Frog come into play again. “Thus Says the Grand Mufti” is like Simon Says, with the players obliged to distinguish between “Thus says…” and “So says…” (A mufti is an Islamic jurist, and at the time the book was published “Grand Mufti” referred to the chief mufti of the Ottoman empire, made topical in Great Britain by the Crimean War of 1853-56.)

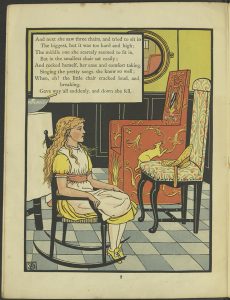

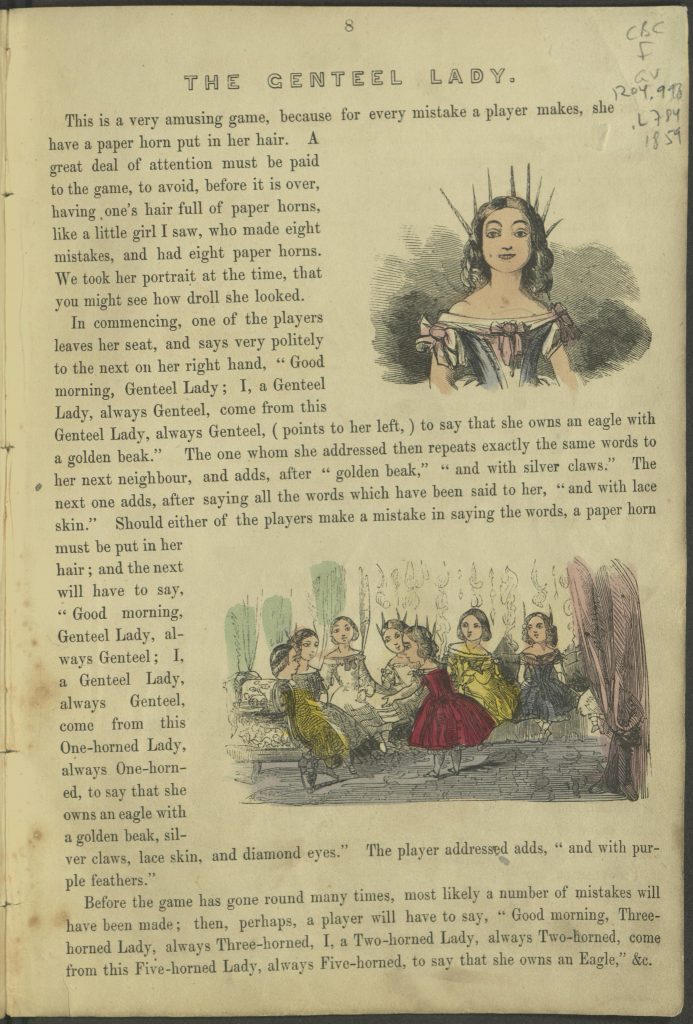

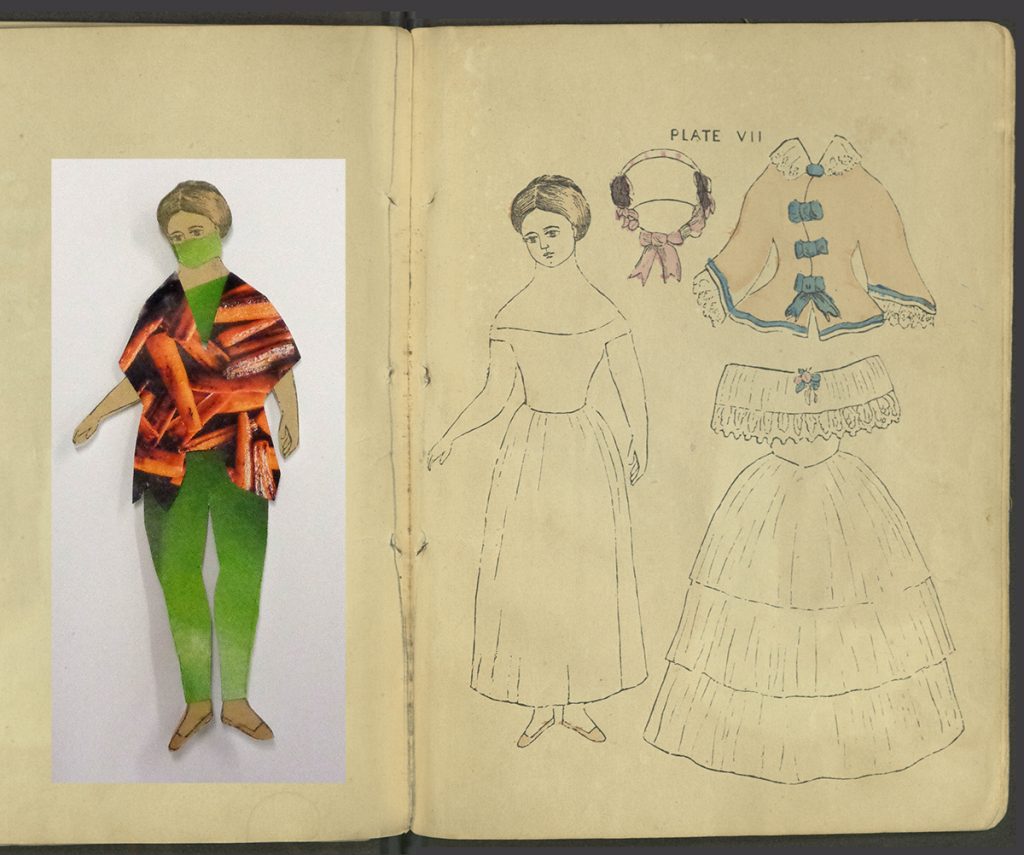

Quicker and easier than forfeits, and one suspects more likely to promote general hilarity, is the “punishment” of adding a paper horn to one’s coiffure after making an error in reciting an increasingly complex series of silly sentences. “The Genteel Lady” is the last game in the book, and in many ways its highlight, with two illustrations (hand-colored wood engravings) and a long set of instructions.

It’s easy to imagine that this book, like most of Dean & Sons’ carefully considered and promoted offerings, was successful. It was attractive and included fifteen games, with a mix of active and intellectual pursuits, indoor and outdoor amusements, and games that could be played instantly as well as some that required equipment or preparation – and all for sixpence (less than $5 today).

– Marianne Hansen, Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts

Cousin Lively’s Picture Book of Nice Little Games for Nice Little Girls. London: Dean & Son. 1859

Our copy of the book can be read on the Internet Archive.

With the continuing closure of the Library, we are blogging regularly about books from the exhibition, The Girl’s Own Book. The exhibition’s run has been extended through the 2020-2021 academic year. Information about when it will open to visitors and related programming will be available when we are able to give it. Please follow us on Facebook or subscribe here for notices of new blog posts.

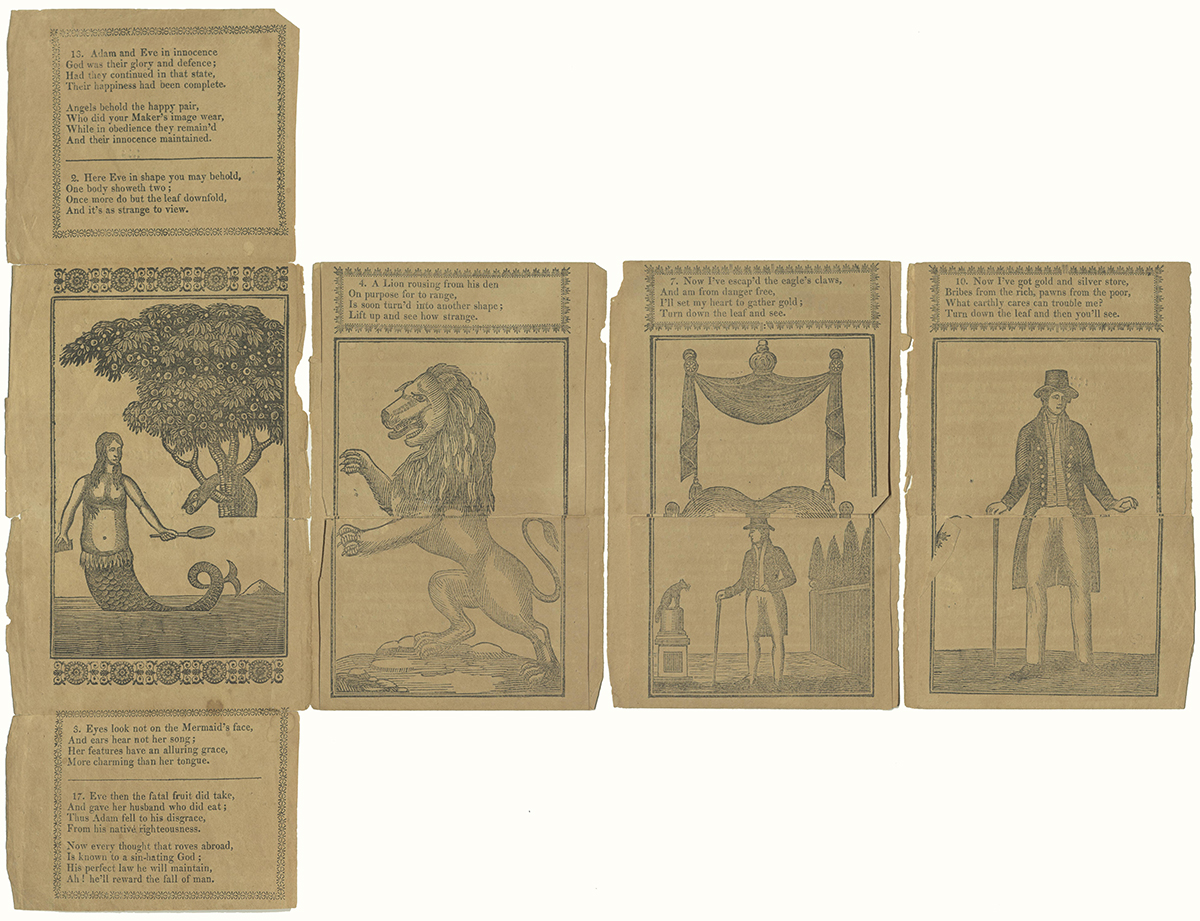

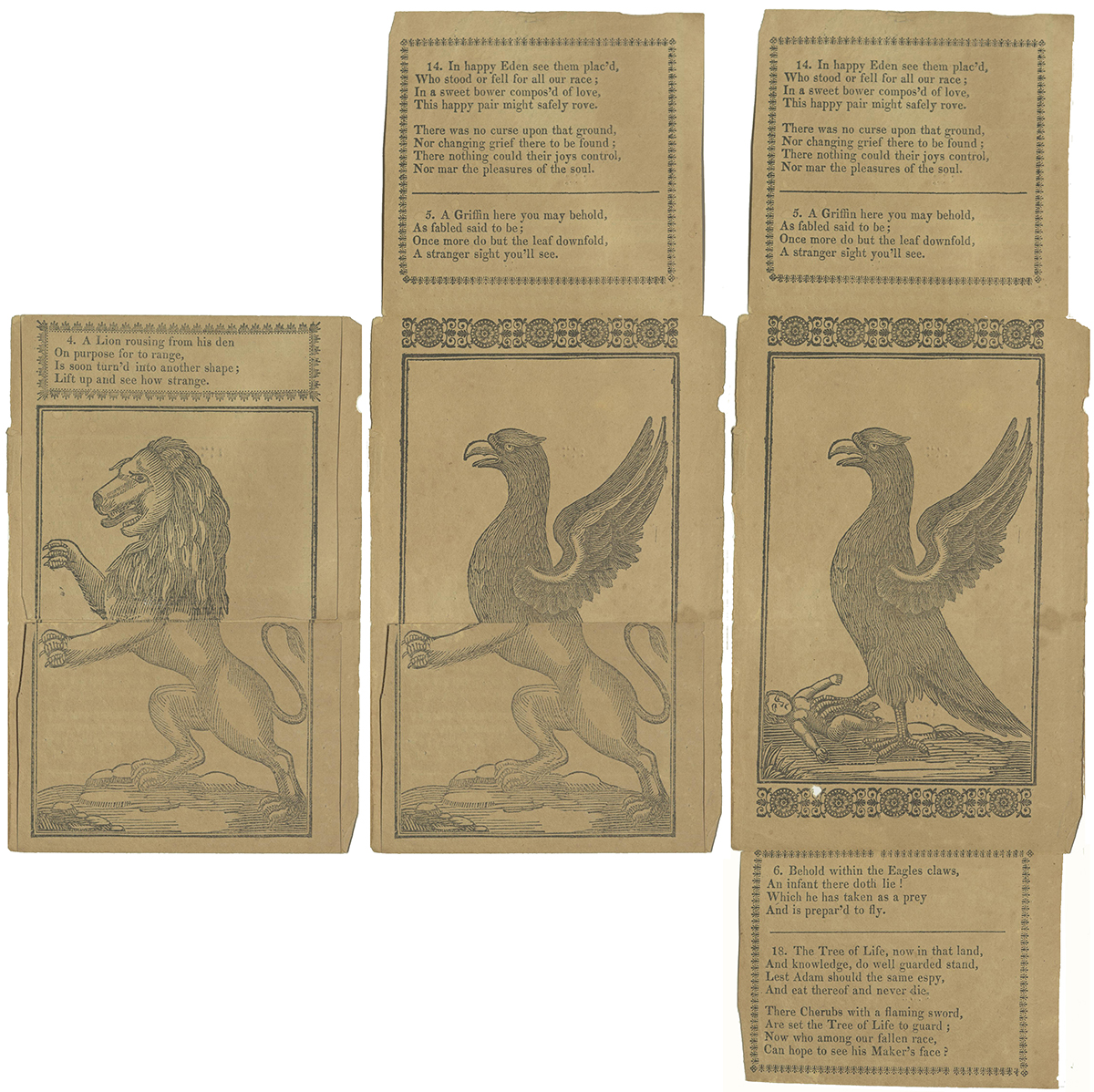

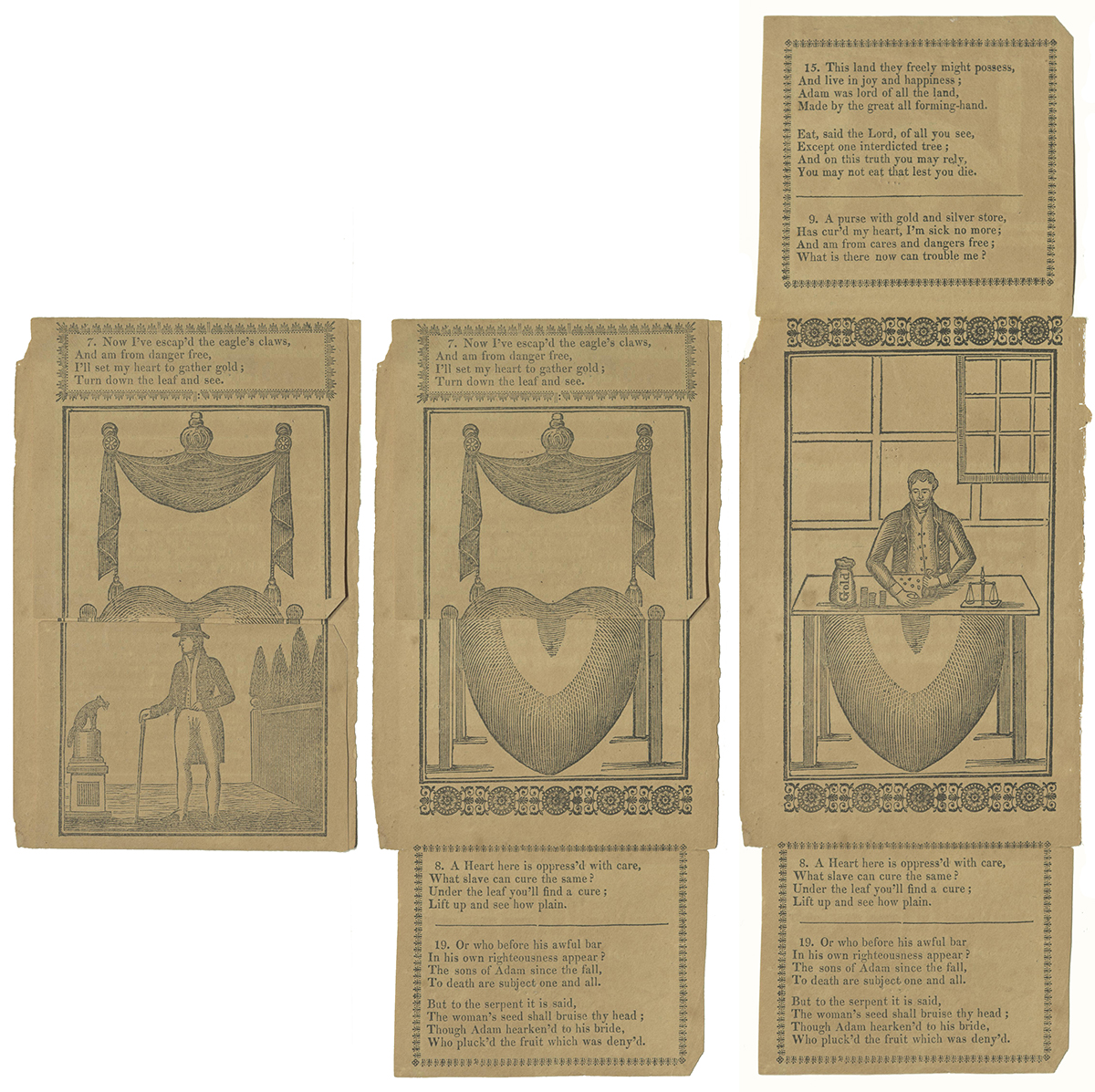

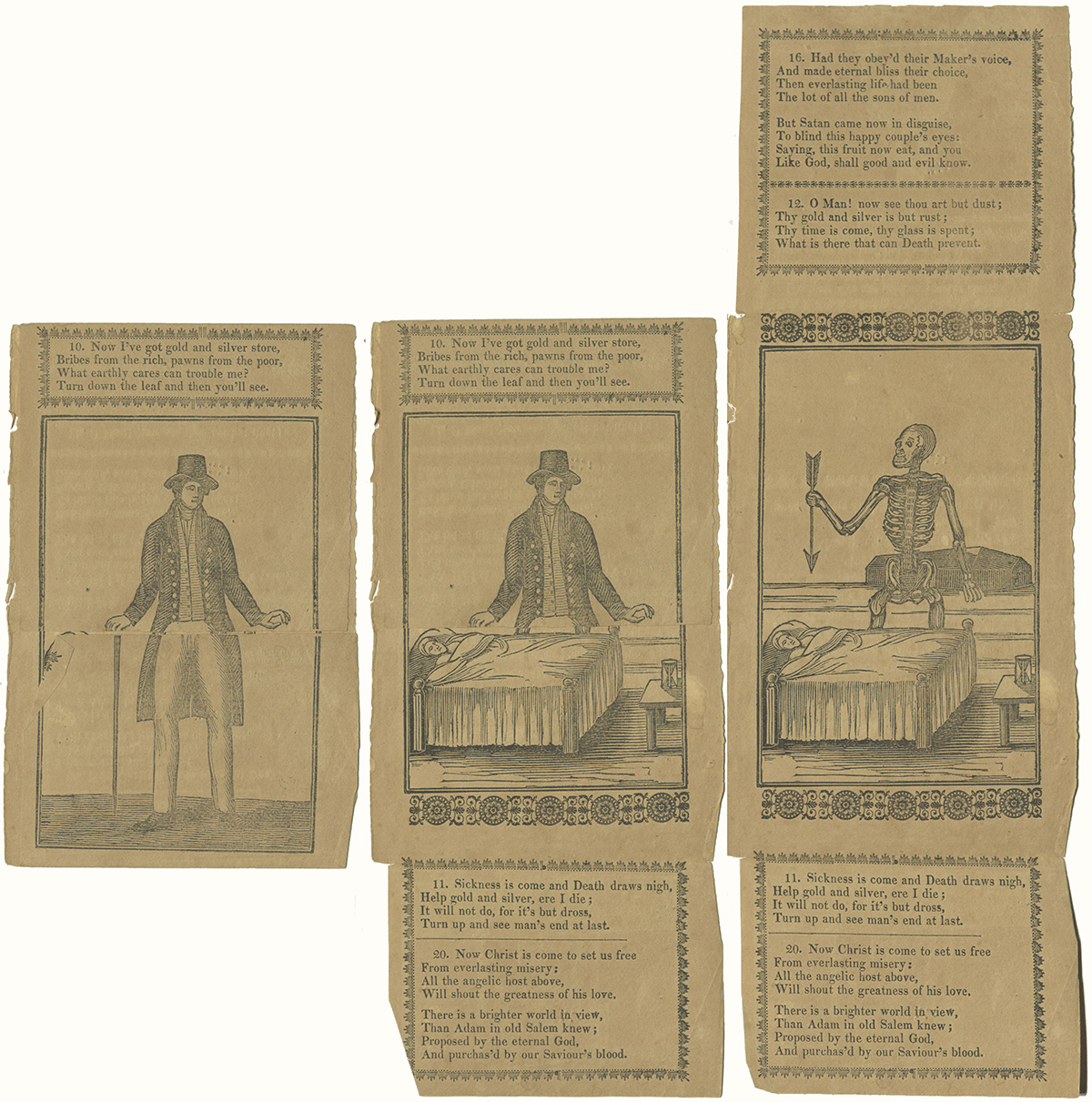

![Verse 13: Adam and Eve in innocence, God was their glory and defence : Had they continued in that state, Their happiness had been complete. Angels, behold the happy pair, Who did your Maker’s image wear, While in obedience they remain’d And their innocence maintained. Verse 14: In happy Eden see them plac’d, Who stood or fell for all our race; In a sweet bower, composed of love, This happy pair might safely rove. There was no curse upon that ground, Nor changing grief there to be found: There nothing could their joys controul [sic], Nor mar the pleasures of the soul. Verse 15: This land they freely might possess, And live in joy and happiness: Adam was lord of all the land, Made by the great all-forming hand. Eat, said the Lord, of all you see, Except one interdicted tree; And on this truth you may rely, You may not eat that lest you die. Verse 16 (not numbered): Had they obey’d their Maker’s voice, And made eternal bliss their choice, Then everlasting life had been The lot of all the sons of men. But Satan came now in disguise, To blind this happy couple’s eyes: Saying, this fruit now eat, and you Like God, shall good and evil know.](http://specialcollections.blogs.brynmawr.edu/files/2020/06/13through16.jpg)