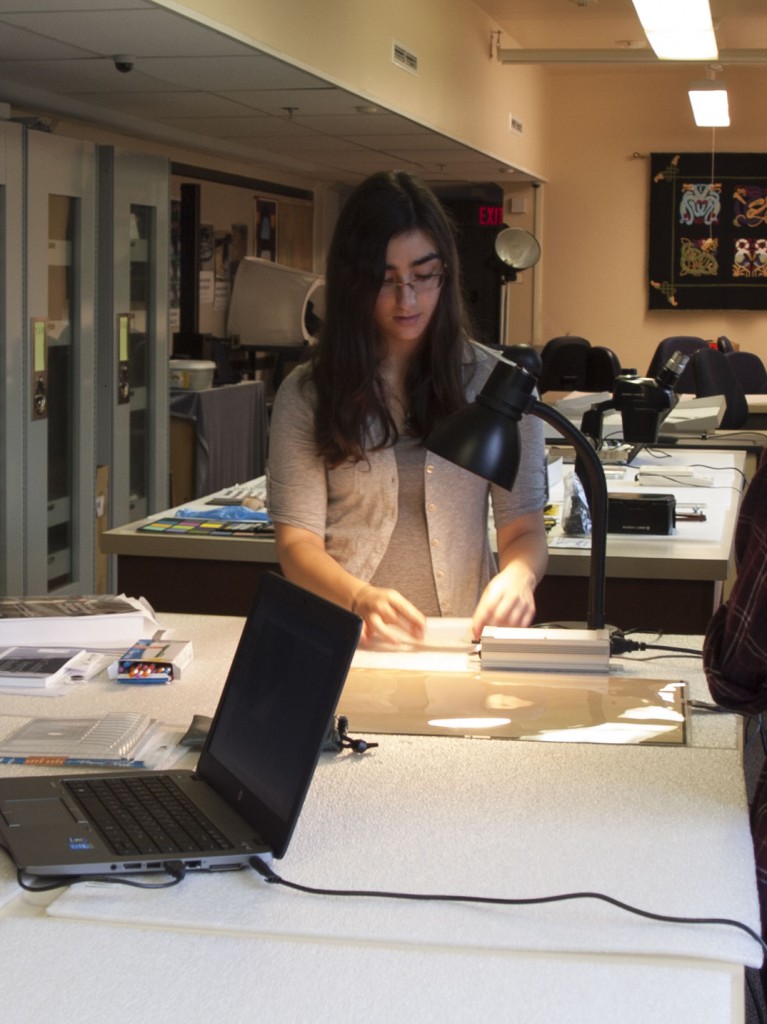

The second lab focused on the examination processes one walks through to get acquainted with an object.

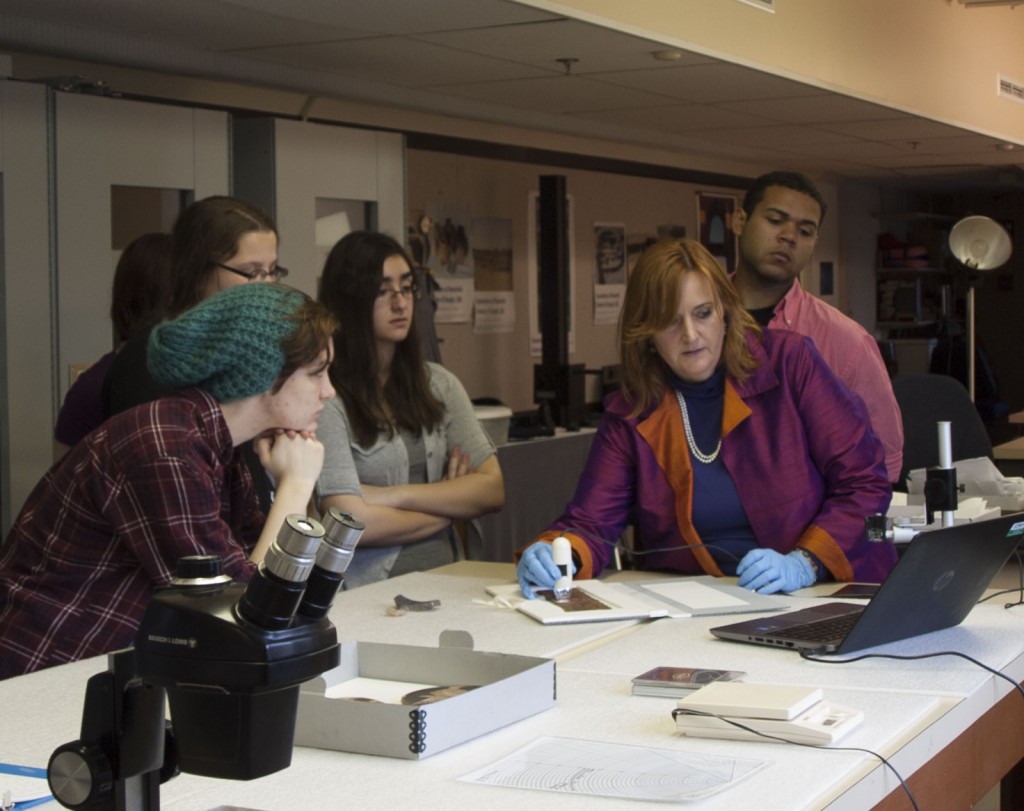

Marianne demonstrated several different ways to look at and manipulate an object to learn more about it. First the class examined a Laconian kylix (cup) and an Attic jug under ultraviolet light, as the repairs made the vessels can be made clearer under UV light.

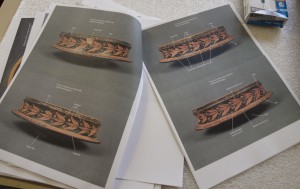

Marianne also demonstrated how different materials appear under different lighting conditions including infrared light and raking light. For example, the presence of carbon containing inks may become clearer under IR light, which can be used to see the under-drawing of a painting. On a fragment of pottery, when examined under raking light, one could see the outline of a different shape (a kylix or cup) underneath the final image of an amphora (storage vessel).

Step 2: Under Raking light, a small kylix (cup) can be seen in outline inside the area of the red amphora (storage vessel)

Professor Lindenlauf and Marianne explained how magnification can elucidate the fabric of a vessel to understand how it was manufactured or the average number of warp and weft threads per centimeter in a Coptic textile.

In addition to spending time really looking at an object to discover more about it, Marianne explained that if an object represents a known type, research can help point to features that one may not be able to see, but can be found if you look. For example, Marianne demonstrated how when air moves through a pair of Peruvian pots, the vessel whistles. The whistling would occur when the vessel was tipped to pour out liquids.

Color cards for photographs, Munsell charts for pottery, and Pantone color cards for fine arts all increase one’s ability to accurately document color. Calipers, rulers, scales, and vessel diameter charts quantitatively describe an object’s size, shape, and weight.

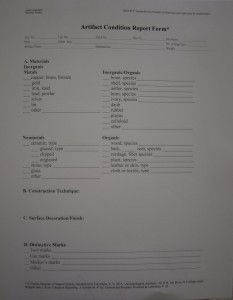

All of the data gathered about the object would go into a condition report. Marianne and Professor Lindenlauf walked through some of the processes with a vessel by the Bryn Mawr Painter and recorded the data on a sample condition report form.

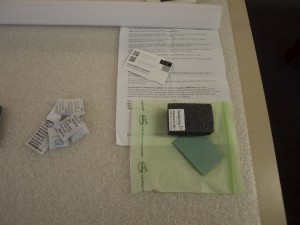

In addition, the class learned how accession numbers are applied to objects. Each object has its own unique accession number that identifies it within the collection. In order to ensure that an object is always identifiable, this number is attached to the object in a variety of ways. Marianne demonstrated two different techniques. For metal, stone and ceramic objects, a small layer of acrylic resin (Acryloid B72 in Acetone) is applied to create a base layer upon which the accession number can be written in permanent ink or acrylic emulsion artist paints. The resin protects the object from the ink and can easily be removed with acetone. In addition, a top coat of a different resin (Acryloid B67 in Naptha) is applied to protect the number from smudging or wear. Another type of label that can be used is a small piece of cotton twill tape with the number written on it which can be applied with a few tacking stitches to a textile object (as long as the object is in good condition and sturdy enough for this type of numbering system).