Bryn Mawr College Special Collections is in the final stages of reorganizing and cataloging the papers of one of the college’s most cherished alumnae, the poet Marianne Craig Moore (Class of 1909). The Marianne Craig Moore Papers consist of 23 boxes of correspondence, photographs, audio recordings, manuscripts, news clippings, and ephemera. We can also boast that we have in our collection one of Marianne Moore’s cloaks, her briefcase with the monogram “M.M.,” and one of her iconic tricorner hats! These materials were given to Bryn Mawr by many donors including Hildegarde and J. Sibley Watson, Jr., Sallie Moore and Marianne Craig “Bee” Moore, Mary Woodworth, Anna Marcet Haldeman-Julius, K. Laurence Stapleton, and many Bryn Mawr alumnae. The collection reveals unique aspects of Marianne Moore’s education at Bryn Mawr.

Bryn Mawr College Special Collections is in the final stages of reorganizing and cataloging the papers of one of the college’s most cherished alumnae, the poet Marianne Craig Moore (Class of 1909). The Marianne Craig Moore Papers consist of 23 boxes of correspondence, photographs, audio recordings, manuscripts, news clippings, and ephemera. We can also boast that we have in our collection one of Marianne Moore’s cloaks, her briefcase with the monogram “M.M.,” and one of her iconic tricorner hats! These materials were given to Bryn Mawr by many donors including Hildegarde and J. Sibley Watson, Jr., Sallie Moore and Marianne Craig “Bee” Moore, Mary Woodworth, Anna Marcet Haldeman-Julius, K. Laurence Stapleton, and many Bryn Mawr alumnae. The collection reveals unique aspects of Marianne Moore’s education at Bryn Mawr.

At the time of her death in 1972, Marianne Moore was well-known as an innovative and witty modernist poet. She won multiple awards for her books of poetry including the Pulitzer Prize, the Bollingen Prize, The National Book Award, The National Medal for Literature, France’s Croix de Chevalier, and sixteen honorary degrees. Until the time of her final illness in 1969, Moore participated in numerous speaking engagements and graciously gave critical advice to young and upcoming poets. Success had not come quickly or easily for Marianne, however. She faced many challenges in acquiring a college education, being professionally published, and finding a professional position as an editor and writer.

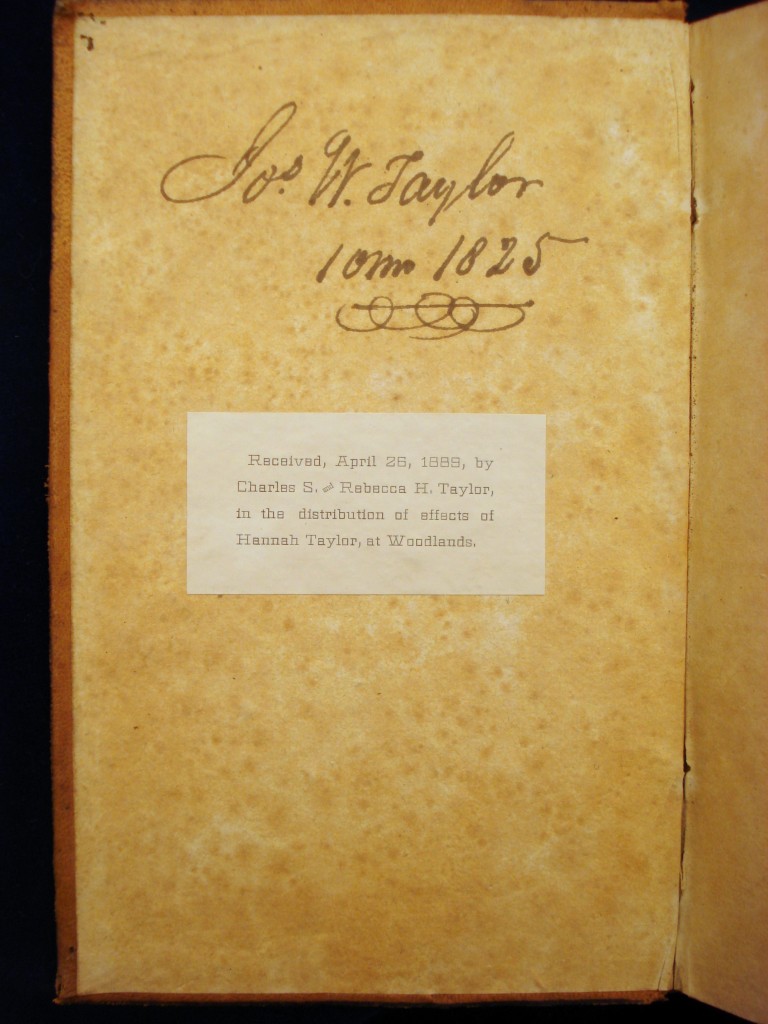

Marianne Moore was born to Mary Warner Moore and John Milton Moore in Kirkwood, Missouri in 1887. Because John Moore suffered a nervous breakdown and was institutionalized before she was born, the poetess never knew her father. Marianne, with her mother and her older brother, moved to Pennsylvania in 1894. While living in Carlisle, PA, Mary Moore worked as an English teacher. A single mother, Mary would continue to hold this job so that both of her children could attend college—John at Yale and Marianne at Bryn Mawr. Details of the financial burden of putting two children through college emerge in the letters Mary wrote to Bryn Mawr. In a letter dated May 2, 1904, Mary Warner Moore wrote: “In replying for my daughter to your announcement that an increase of fifty dollars in the yearly tuition is to be made, I should say that her application still remains good. I am sorry however, that an increase in tuition is necessary. I have been teaching for four years in order to make college education possible for my two children—a son and a daughter, and of course under the new arrangement, the weight is greater…”

And on January 18, 1906, she wrote, “That [Marianne’s] brother is in College, and she likewise, and that I am teaching in order to keep them there, may make apparent the reason of a somewhat frugal ordering of her affairs on Marianne’s part while she is in College, and also of her application for scholarships. The circumstances of our lives have been unusual…”

Their “unusual” family circumstances also made other aspects of attending college difficult for Marianne. In a letter dated September 4, 1905, Mary wrote to Bryn Mawr to ask whether there was any way Marianne could take her English examination on a Monday afternoon rather than in the morning so that Marianne’s brother could escort her to Bryn Mawr. This way, Mary would not have to take off work. Marianne’s mother ended the letter,

“[Marianne] has never traveled alone, however, and I am not willing to have her make the journey, and its several changes, alone.”

Unfortunately, her request was not granted. In the next letter dated September 11, 1905, Marianne’s mother thanked Bryn Mawr for refusing her request politely. Seeming thoroughly embarrassed, she replied, “That I, a teacher, should be guilty of proposing a disorderly act, seems most reprehensible.”

In Fall of 1905 Marianne arrived at Bryn Mawr. She wanted to be an English major; her love of reading and writing had started at a young age. She was thwarted, however, by her English professors who said that she was obscure and unclear in her writing and that she often disregarded rules of grammar and language. Ironically, these characteristics would be hallmarks of her famous, modernist poetry. Marianne continued to write while at Bryn Mawr, publishing short stories and poems in Tipyn O’Bob and The Lantern. She also wanted to major in biology but was apparently discouraged by her mother who thought that being a biologist was no profession for a lady. Nevertheless, flora, fauna, and the sea were frequent subjects of her poetry.

Marianne graduated from Bryn Mawr with a B.A. in history, economics, and politics in 1909. It took six years after graduating Bryn Mawr before she was published professionally. After moving to New York with her mother, she befriended J. Sibley Watson, Jr. and Scofield Thayer, owners of The Dial, a popular magazine which served as an outlet for modernist thought, art, and literature. Watson and Thayer were so impressed with Marianne Moore that they made her acting editor of their magazine in 1925 and editor-in-chief in 1926. She was editor until 1929 when The Dial ceased publication.

Jennifer Hoit Dawson

Ph.D. Candidate in Greek, Latin & Classical Studies