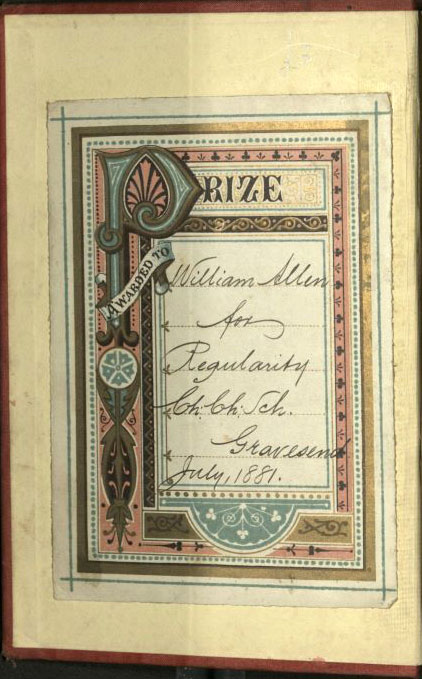

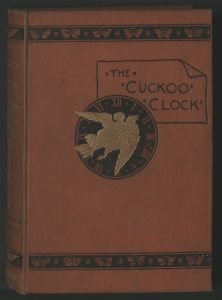

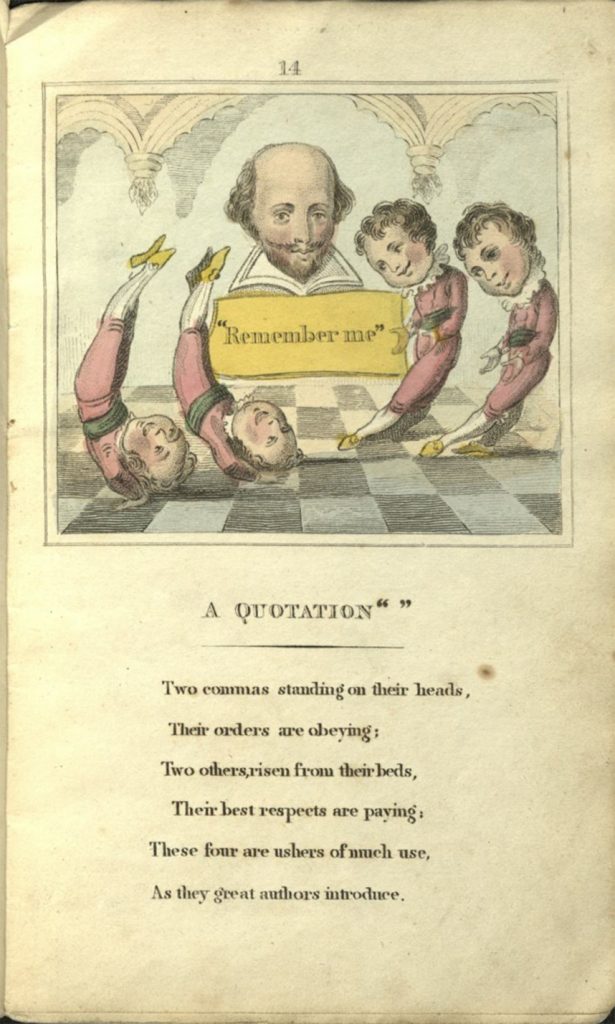

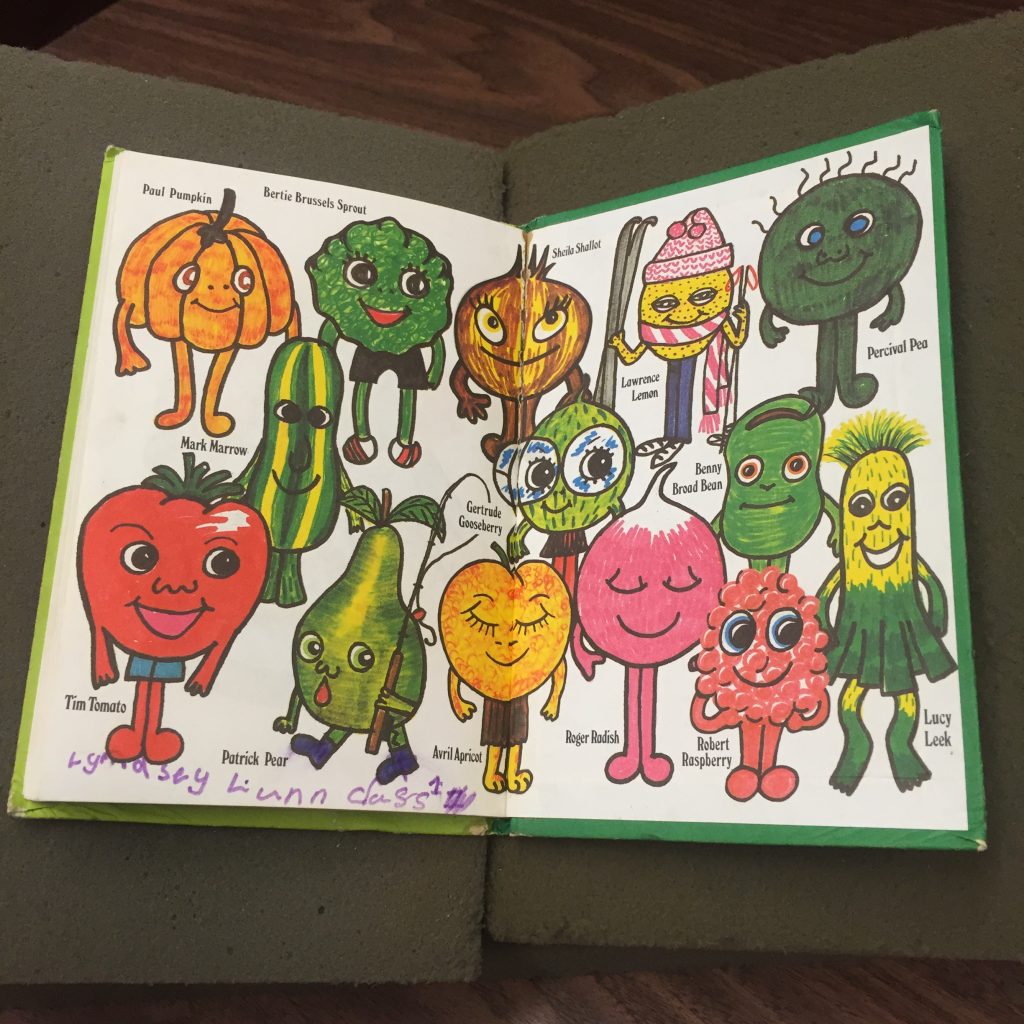

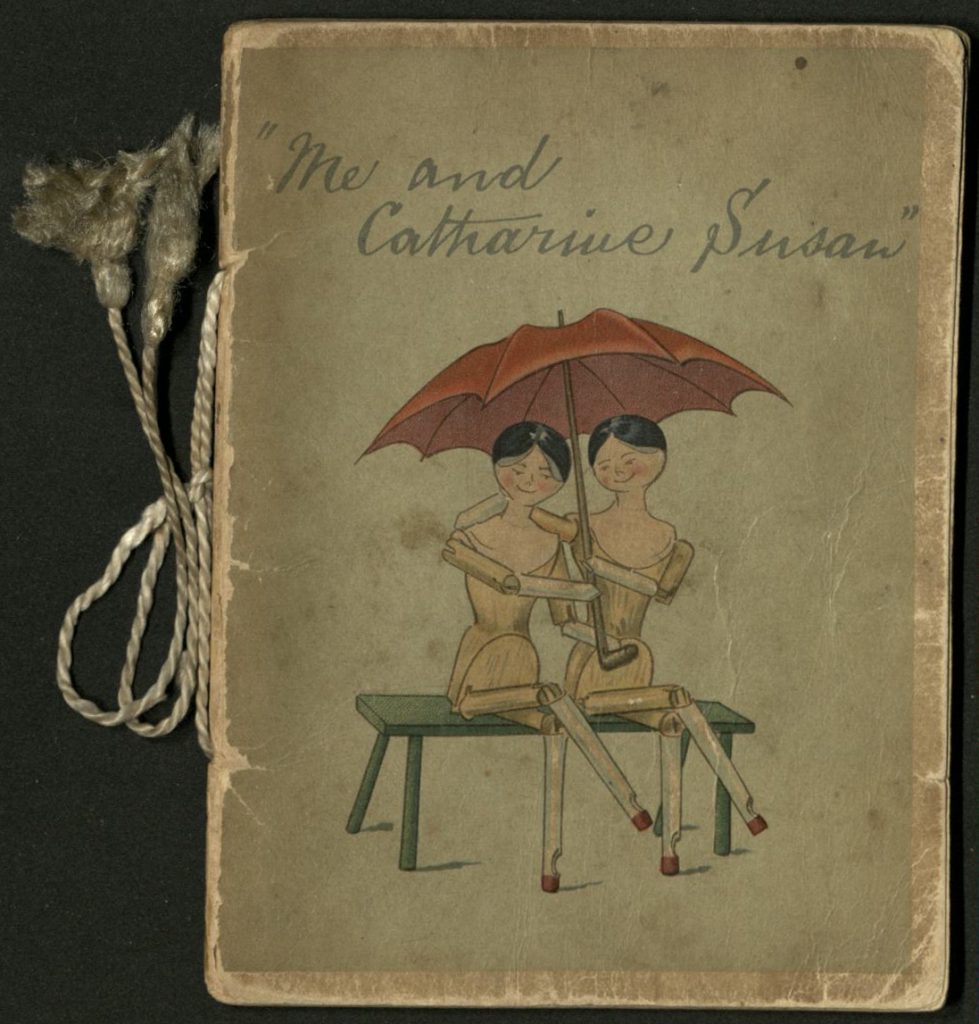

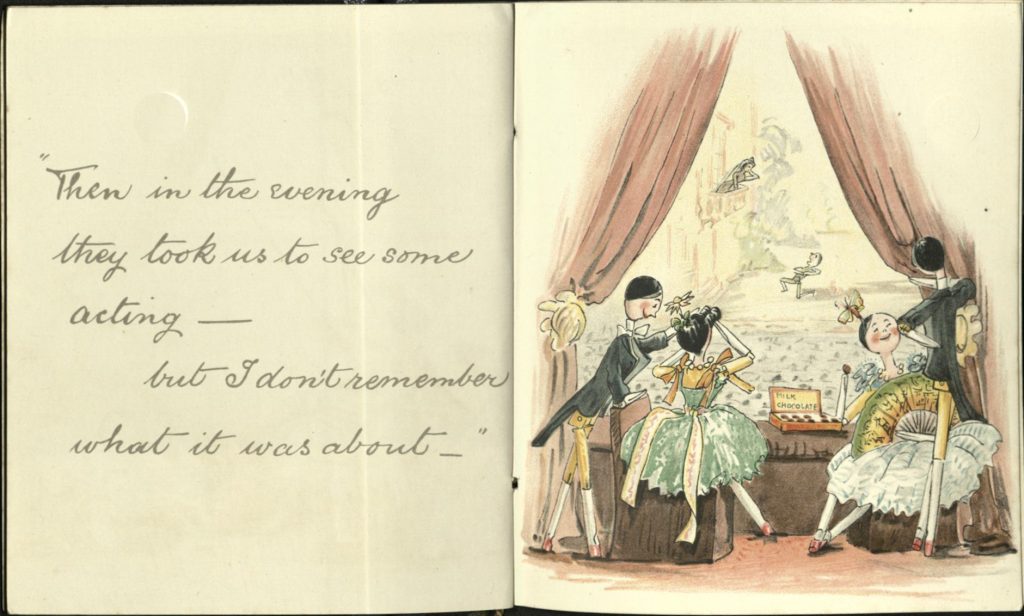

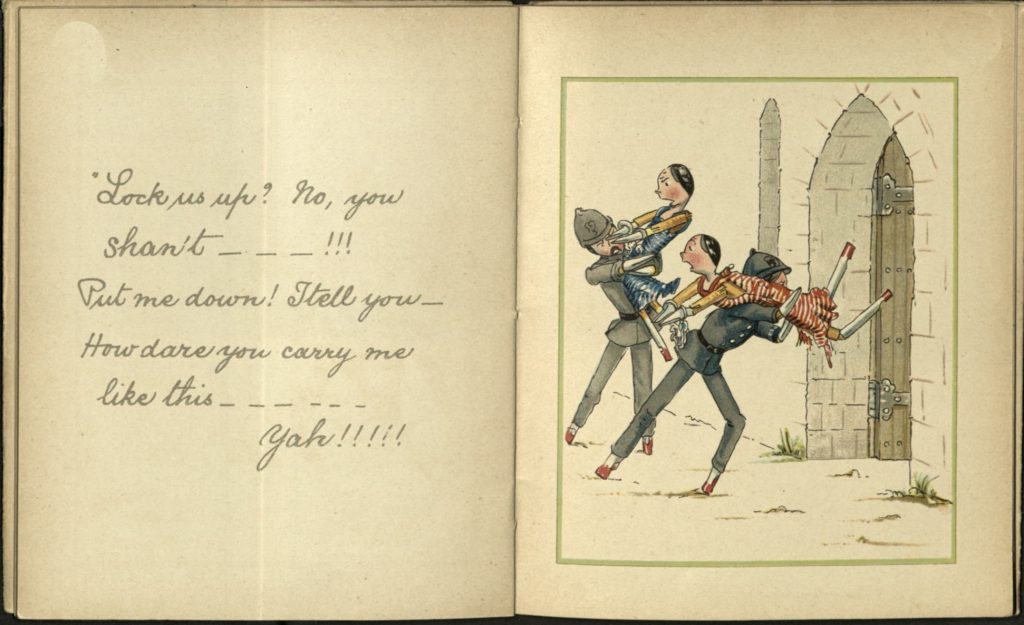

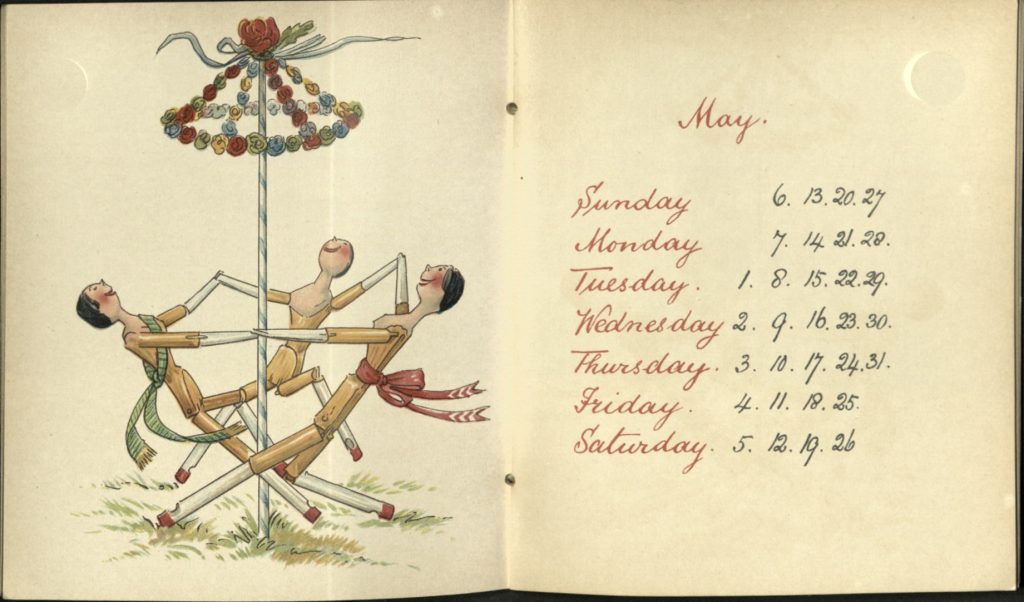

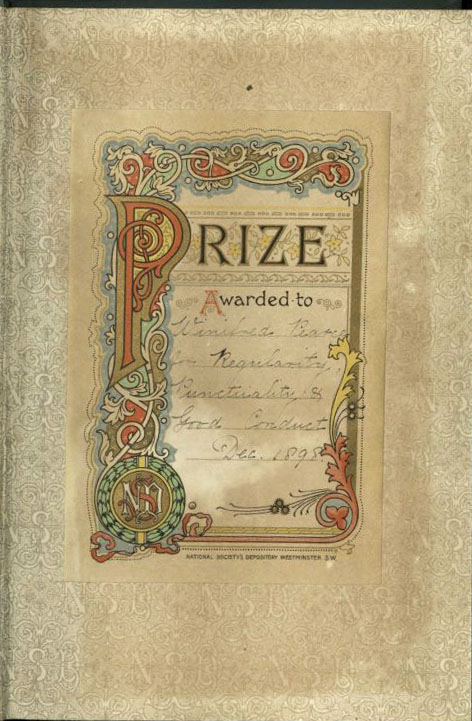

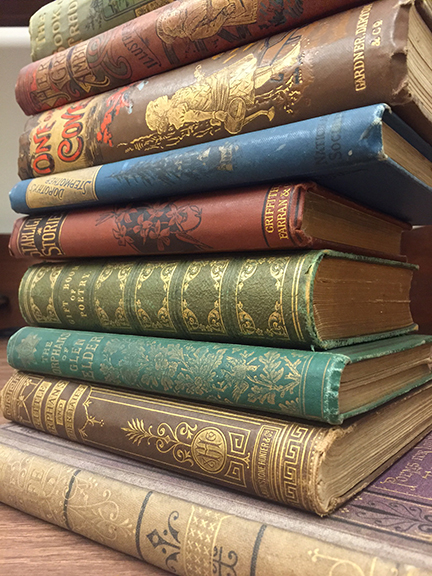

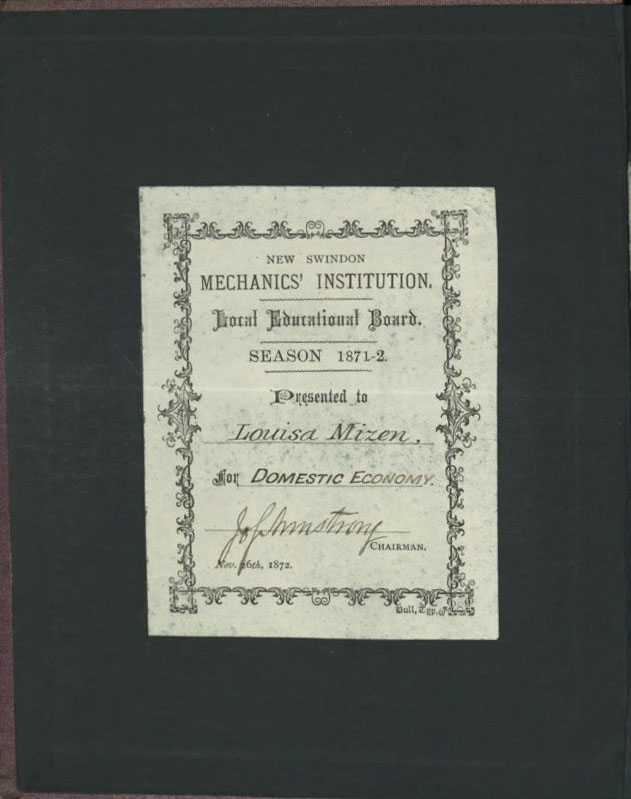

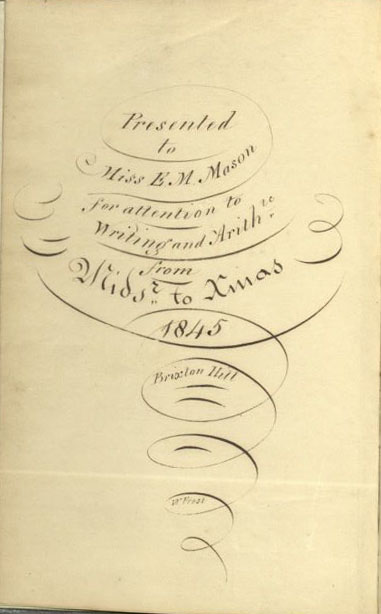

Many of the Wood Collection books from the turn of the twentieth century are prize books (also referred to as reward books or premiums). Prize books were presented to children by schools, Sunday schools and religious associations as rewards for attendance, good behavior, or academic achievement. Prize books typically have an inscription or bookplate with the student’s name and the name of the awarding institution, along with the reason for the prize.  Books awarded during the boom in popularity of prize books might also have more elaborate bindings and gilt edges.

Books awarded during the boom in popularity of prize books might also have more elaborate bindings and gilt edges.

The practice of giving children books as a reward has a long history, but the emergence of the prize book market and the significant role that these books played in the children’s book publishing industry have their roots in England’s Elementary Education Act of 1870. This Act introduced compulsory education for all children and the development of school boards to oversee children’s education in areas where new schools would be needed.

The practice of giving children books as a reward has a long history, but the emergence of the prize book market and the significant role that these books played in the children’s book publishing industry have their roots in England’s Elementary Education Act of 1870. This Act introduced compulsory education for all children and the development of school boards to oversee children’s education in areas where new schools would be needed.

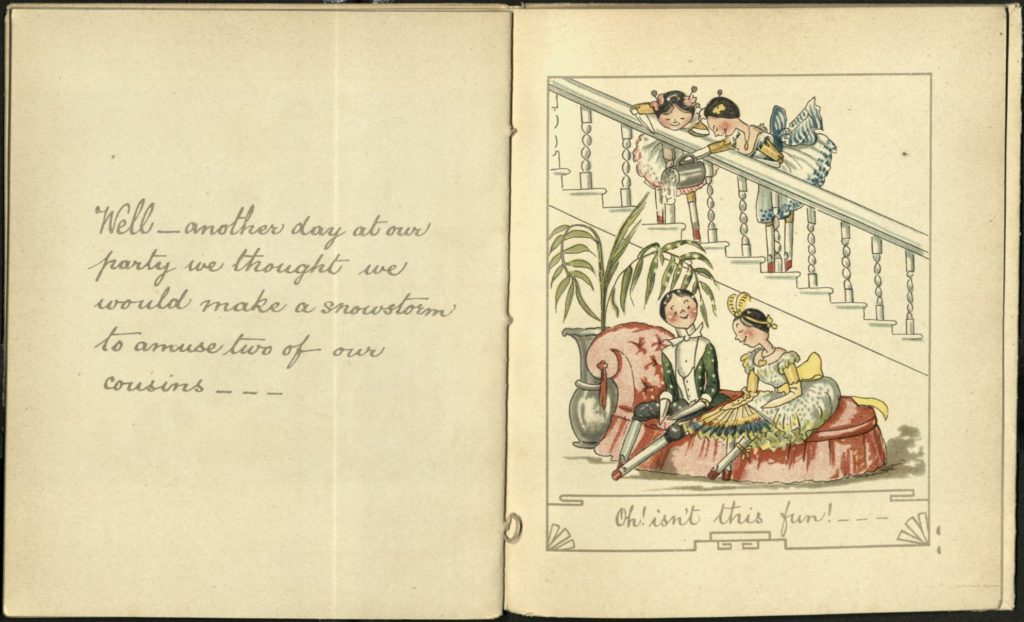

As the responsibility for children’s education shifted away from the church, concerns (expressed by religious and secular leaders alike) about popular juvenile fiction and the lack of appropriate models of behavior grew. The books that children received as prizes naturally reflected the values of the awarding institutions. Thus, books emphasizing the importance of hard work, temperance, and dedication to family values were typical prizes. Even when awarded by Sunday schools or other religious organizations, most prize books were not overtly religious, but encouraged piety and morality couched in social expectations for acceptable and respectable behavior.

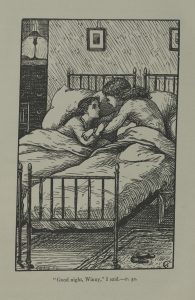

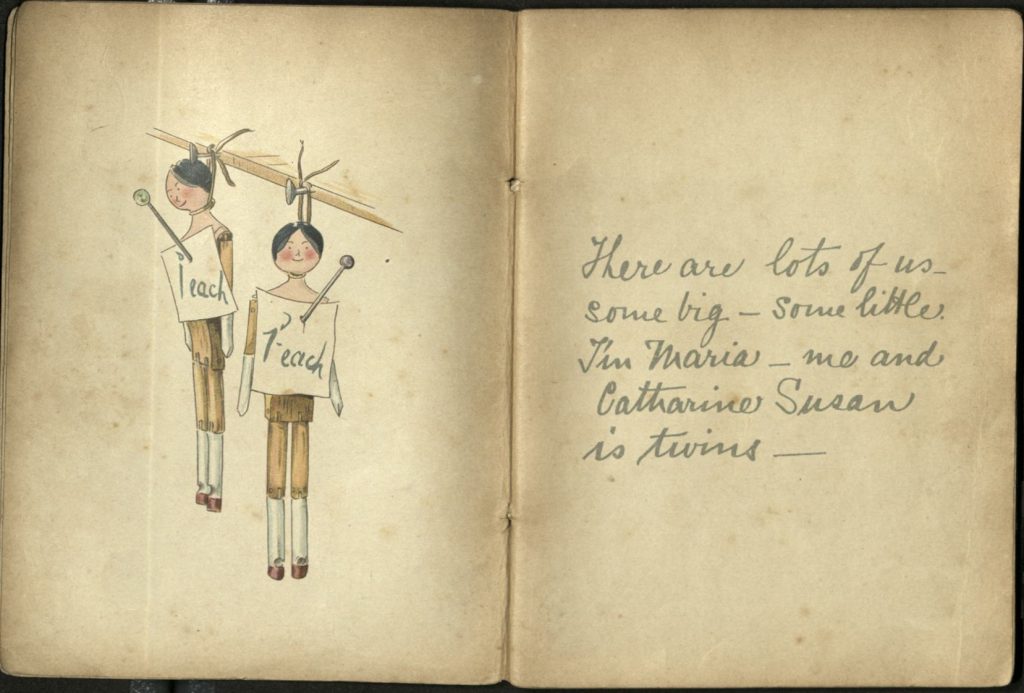

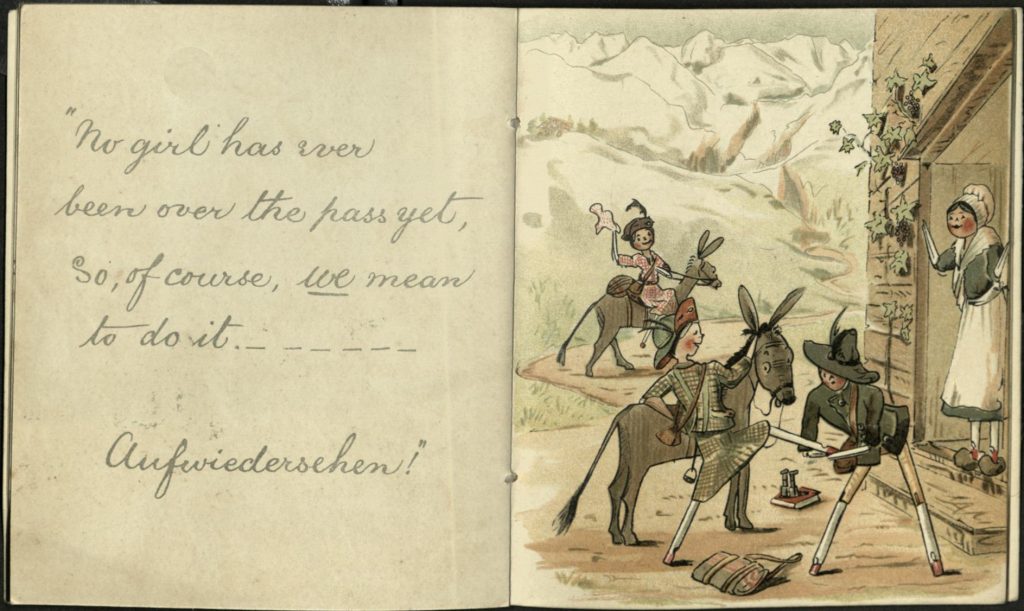

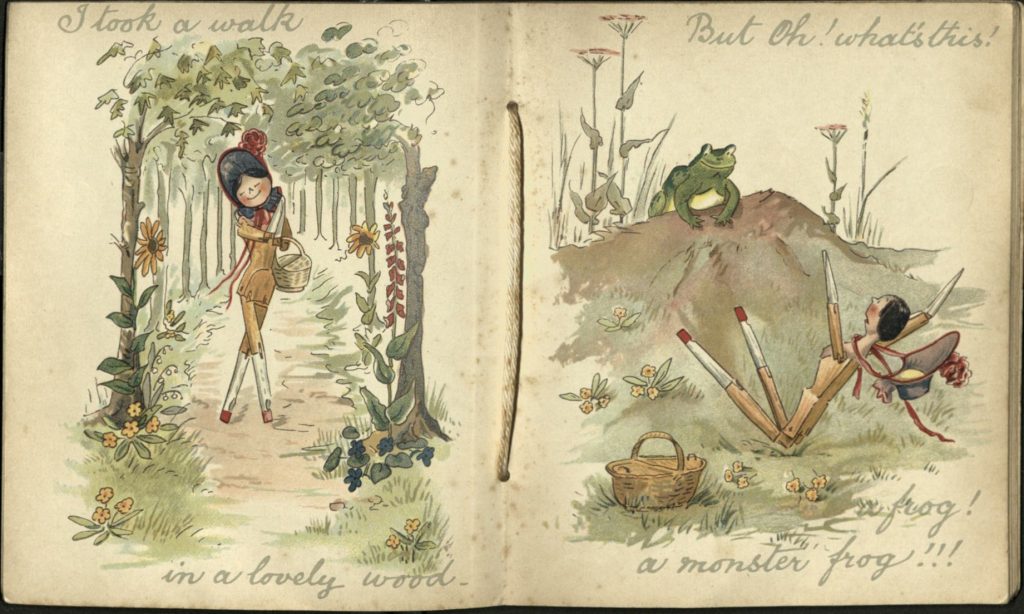

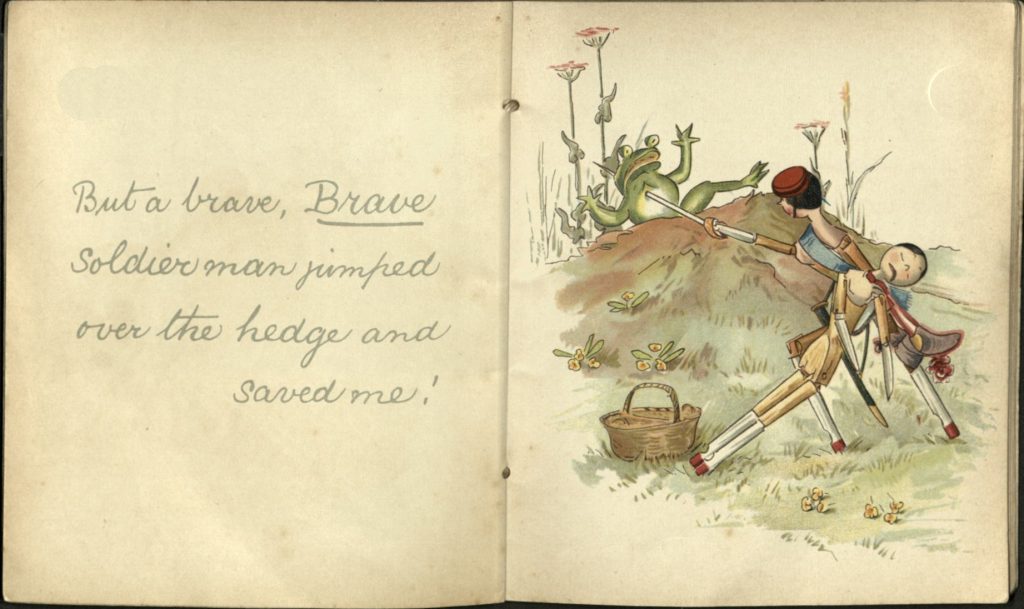

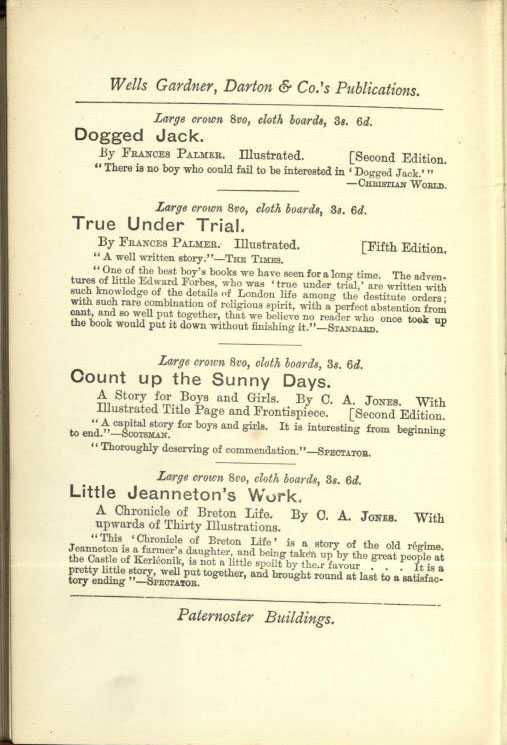

Though rarely the main focus of the narrative, much of the appropriate behavior modeled in prize books reinforced traditional gender roles. Portrayals of boys and men were complicated in that they had to reinforce some traditional male characteristics while disregarding others – boys behaving appropriately in these books would be hard working and relatively independent, but not adventurous like the heroes in popular fiction.

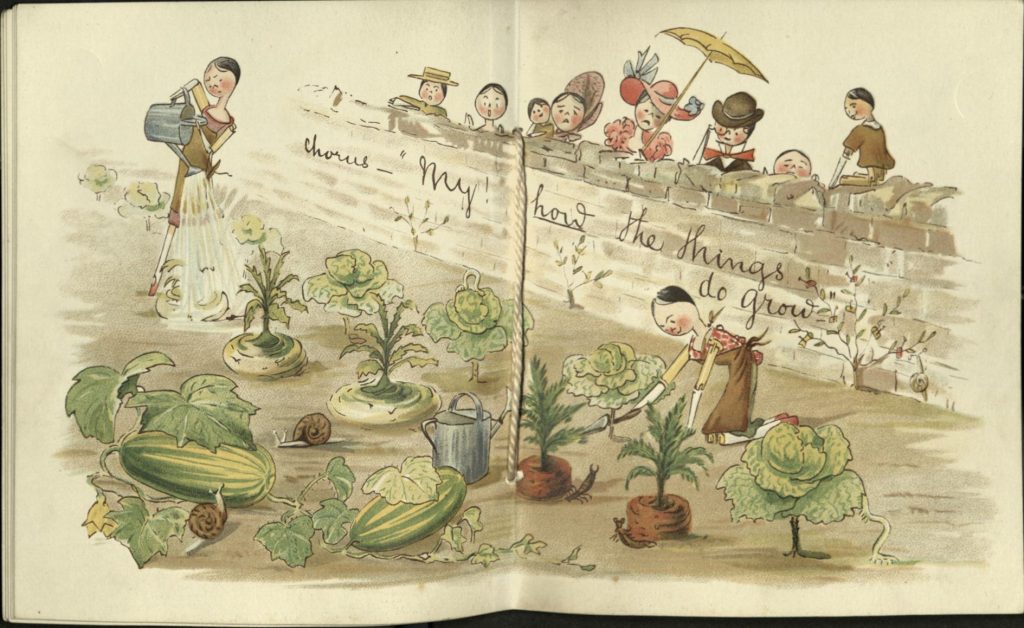

Though rarely the main focus of the narrative, much of the appropriate behavior modeled in prize books reinforced traditional gender roles. Portrayals of boys and men were complicated in that they had to reinforce some traditional male characteristics while disregarding others – boys behaving appropriately in these books would be hard working and relatively independent, but not adventurous like the heroes in popular fiction. Representation of girls and women was often outdated, stubbornly disregarding changes in women’s roles in society. Even as more women, regardless of marital status, worked outside the home, prize books persisted in the narrow portrayals of women as wives and mothers, planted firmly within the domestic realm.

Representation of girls and women was often outdated, stubbornly disregarding changes in women’s roles in society. Even as more women, regardless of marital status, worked outside the home, prize books persisted in the narrow portrayals of women as wives and mothers, planted firmly within the domestic realm.

Preservation of the status quo was also encouraged with regard to class. For many recipients, prize books were the only ones (other than the Bible) present in their homes. Books were chosen by middle-class boards and teachers, and provided to their working-class students as models of acceptable behavior. Social striving was actively discouraged in many stories and the protagonists held up as model characters were praised for knowing their place in society.

Preservation of the status quo was also encouraged with regard to class. For many recipients, prize books were the only ones (other than the Bible) present in their homes. Books were chosen by middle-class boards and teachers, and provided to their working-class students as models of acceptable behavior. Social striving was actively discouraged in many stories and the protagonists held up as model characters were praised for knowing their place in society.

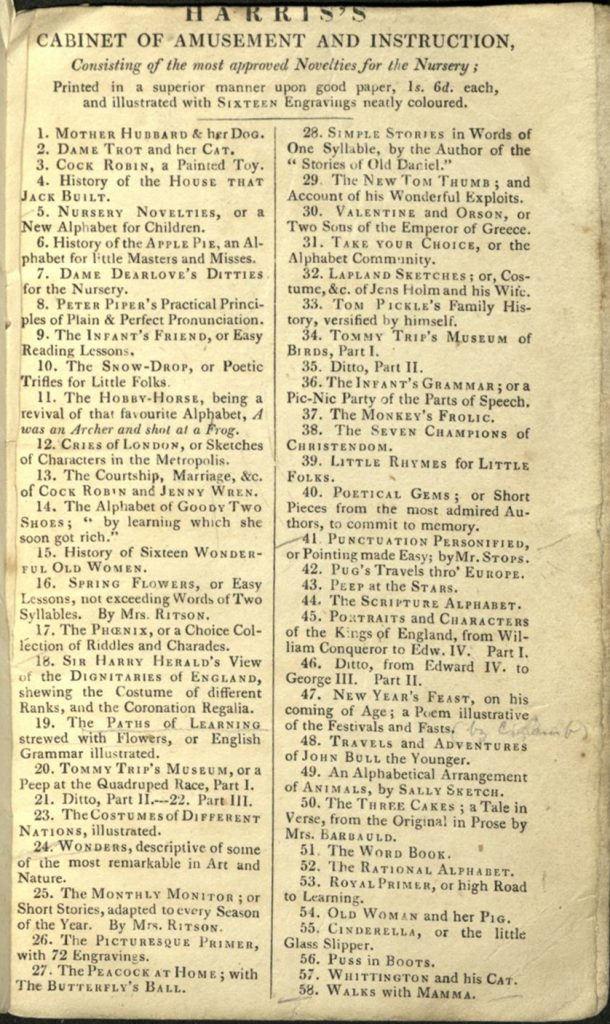

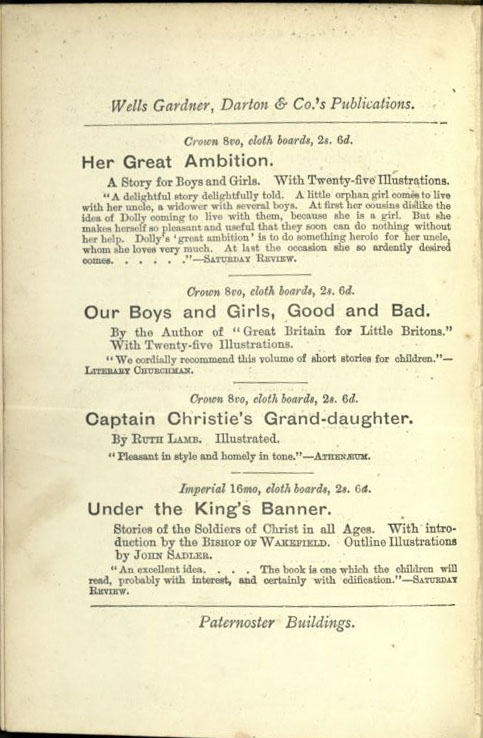

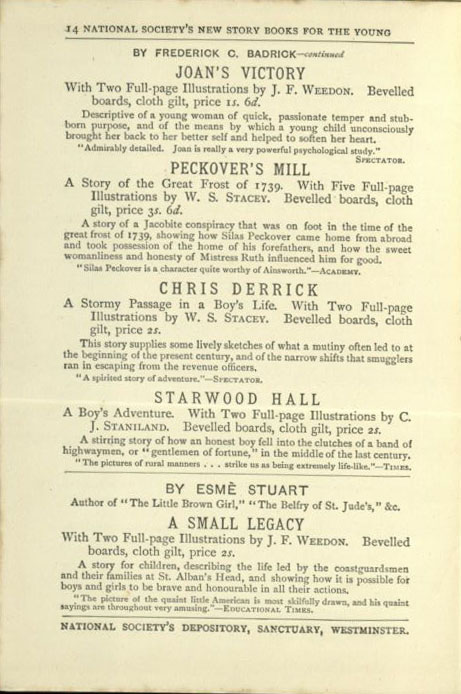

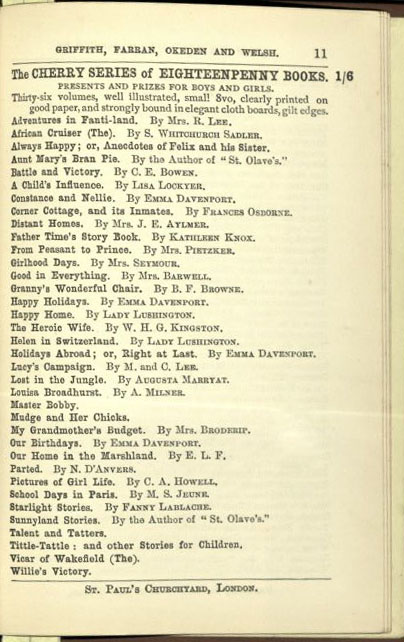

Class distinctions played a pivotal role in the development and prevalence of prize books as a sort of genre as well. While schoolchildren of any class might receive a book as a reward for good conduct or achievement in a certain subject, upper- and middle-class students were more likely to be presented with books chosen specifically with their interests in mind. Meanwhile, working-class students typically received books that were pre-approved by committee and ordered in bulk from a publisher’s list of suggested reward books.

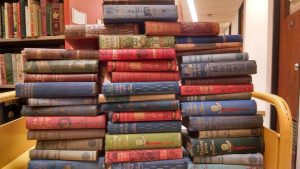

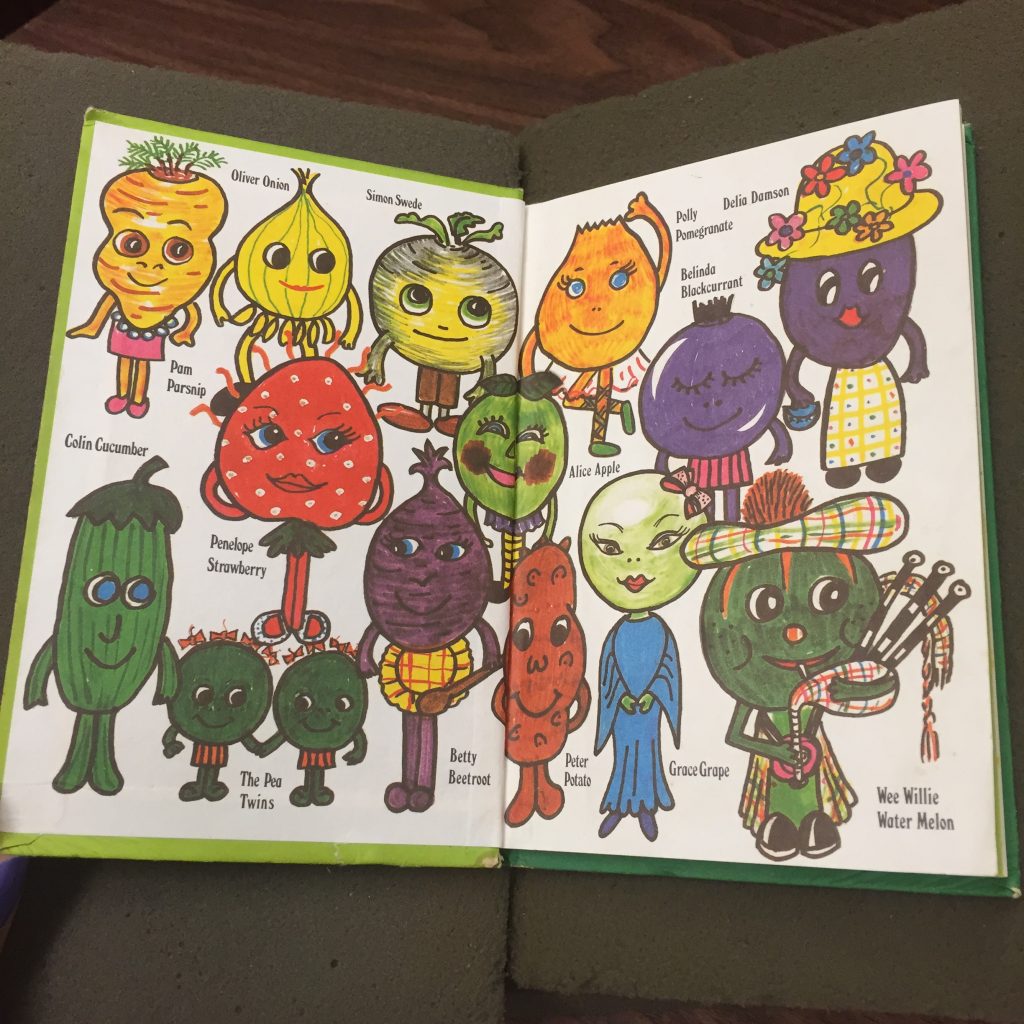

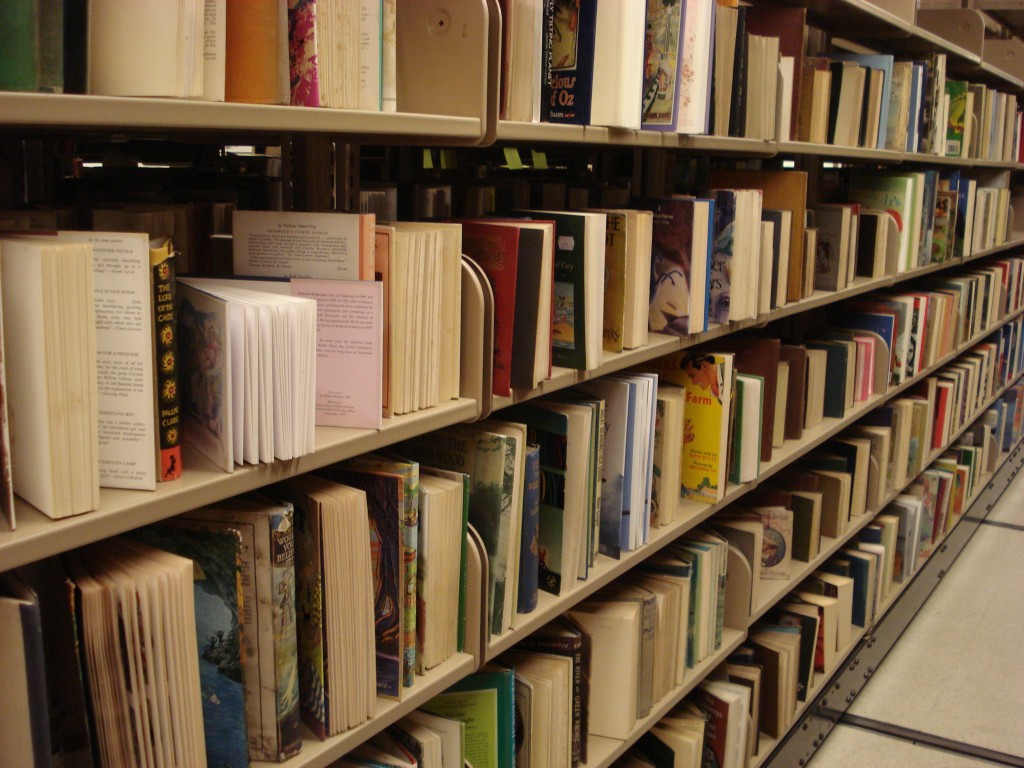

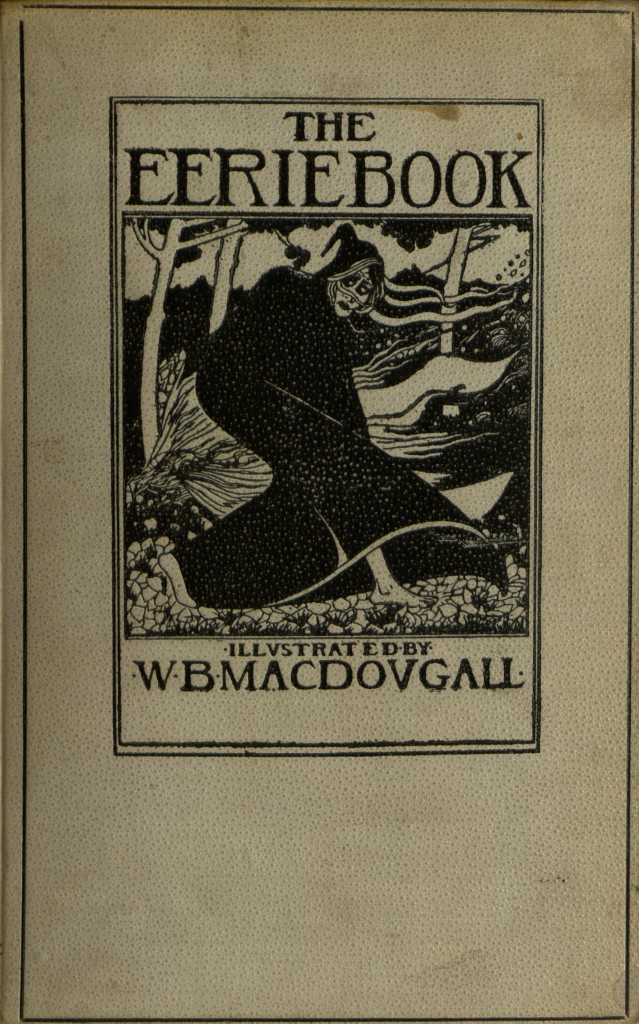

As the practice of awarding these prize books to schoolchildren gained popularity, publishers capitalized on it, searching lists for appropriate titles and producing inexpensive, decorated prize editions. While earlier books (especially those published and presented before the Education Act) had inscriptions or bookplates noting the reward,  prize editions had special bindings, gilt edges, and other decorations to make them stand out and appeal to children.

prize editions had special bindings, gilt edges, and other decorations to make them stand out and appeal to children.

These decorated editions looked fancy, but were often printed in a compressed format on thin, low-quality paper, which kept costs low for publishers and for schools. Institutions could then purchase these books in bulk and award them as-is, or with the addition of an inscription or bookplate with the student’s name, the awarding institution, and the reason for the prize to personalize them for the recipient.

In addition to creating prize and reward series with books already in their catalog, publishers commissioned works for the explicit purpose of promoting them as prize books. These commissioned works were not necessarily held in high literary regard, but as the demand for “suitably moral,” wholesome books persisted, so did publishers. In driving the demand for specific kinds of fiction, prize books played an important role in the development of children’s literature by dictating both content and business models.

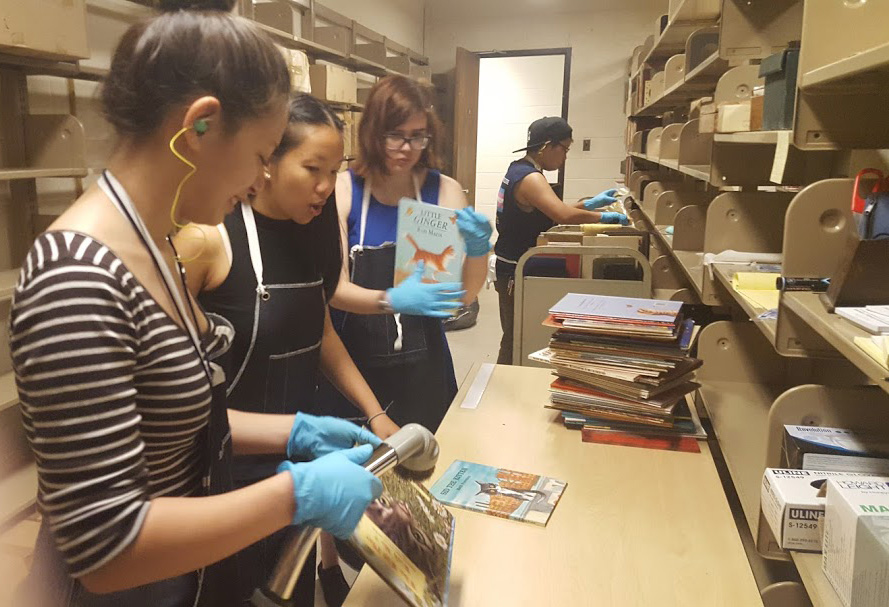

Though special prize editions of books have mostly gone out of style, the practice of rewarding students for academic achievements with books persists. After all, a book is a fitting prize for a student who has shown diligence in her studies and a thirst for knowledge. What better way to encourage further academic achievement than to present a student with something that facilitates it?

Though special prize editions of books have mostly gone out of style, the practice of rewarding students for academic achievements with books persists. After all, a book is a fitting prize for a student who has shown diligence in her studies and a thirst for knowledge. What better way to encourage further academic achievement than to present a student with something that facilitates it?

– Rayna Andrews (BMC 2011), Project Coordinator