Until the end of the eighteenth century, moral literature for the young focused primarily on religious instruction. But changing ideas about childhood resulted in new parenting styles, with increasing emphasis on empathy, reason, and psychological reward and punishment. Books for children began to speak openly of earthly as well as heavenly rewards for good behavior – happiness, parental love, social approbation, and gifts and treats. Naughtiness, similarly, resulted not only in eternal damnation but also in rebuke, deprivation, social isolation, corporal punishment, injury, and even death. Although many of these books also contained religious instruction, morality and behavior drove much of the narrative, rather than piety and belief.  The most successful book of this sort was The Daisy, or, Cautionary Stories in Verse: Adapted to the Ideas of Children from Four to Eight Years Old, attributed to Elizabeth Turner. First published by John Harris in 1807, it was reprinted in England and America throughout the nineteenth century. Half the poems are about good children who are obedient, kind to their pets and their siblings, speak courteously, study hard at school, and are benefactors of the poor. But the more interesting narratives are driven by conflict, and the most memorable characters are ill-behaved. The Daisy is famous for bad things happening to barely naughty people – burned, poisoned, drowned. It is the epitome of the alarmist books that were parodied first by Hoffman’s Struwwelpeter, and later by Gorey in the Gashlycrumb Tinies. To the 21st-century reader it seems absurd to have threatened such dire outcomes of typical childish misbehavior, especially for such a young audience.

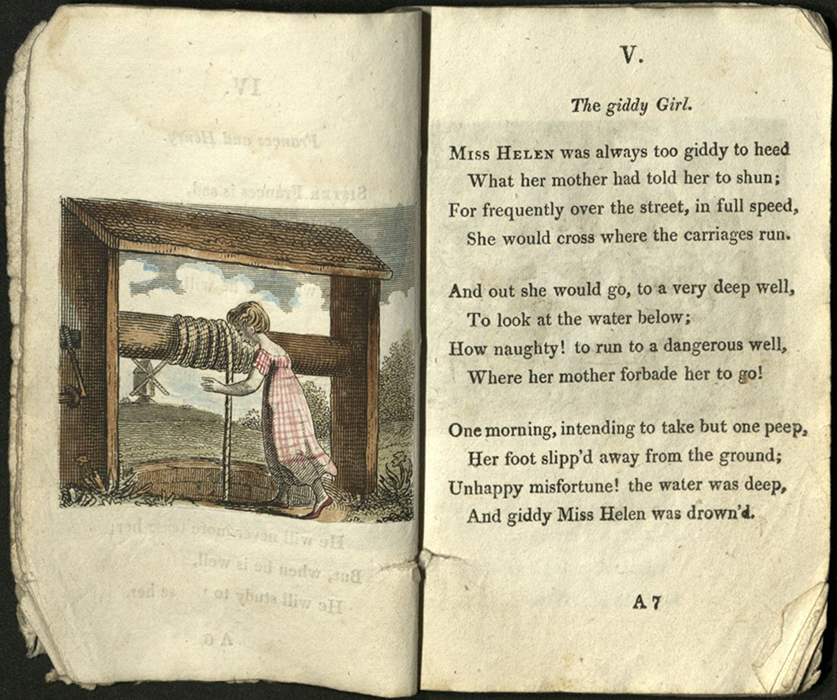

The most successful book of this sort was The Daisy, or, Cautionary Stories in Verse: Adapted to the Ideas of Children from Four to Eight Years Old, attributed to Elizabeth Turner. First published by John Harris in 1807, it was reprinted in England and America throughout the nineteenth century. Half the poems are about good children who are obedient, kind to their pets and their siblings, speak courteously, study hard at school, and are benefactors of the poor. But the more interesting narratives are driven by conflict, and the most memorable characters are ill-behaved. The Daisy is famous for bad things happening to barely naughty people – burned, poisoned, drowned. It is the epitome of the alarmist books that were parodied first by Hoffman’s Struwwelpeter, and later by Gorey in the Gashlycrumb Tinies. To the 21st-century reader it seems absurd to have threatened such dire outcomes of typical childish misbehavior, especially for such a young audience.

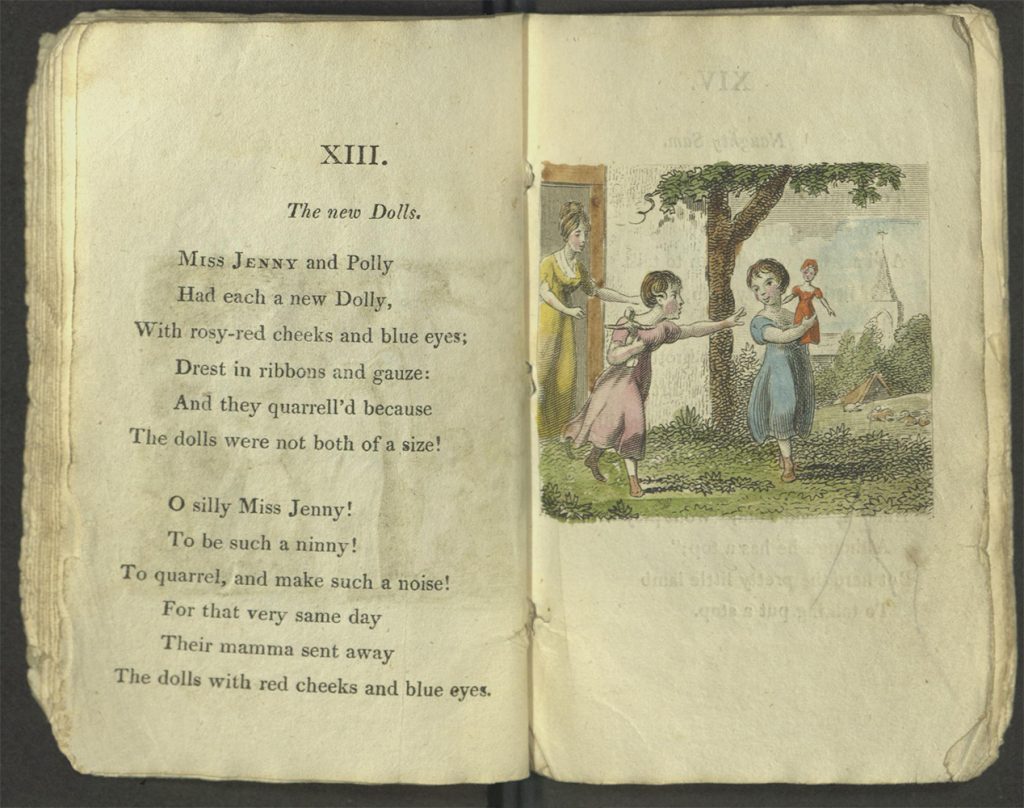

Some of the infractions and punishments do seem reasonable, even to modern feelings. Sisters Jenny and Polly fight over whose new doll is bigger – and their mother takes the dolls away from them.

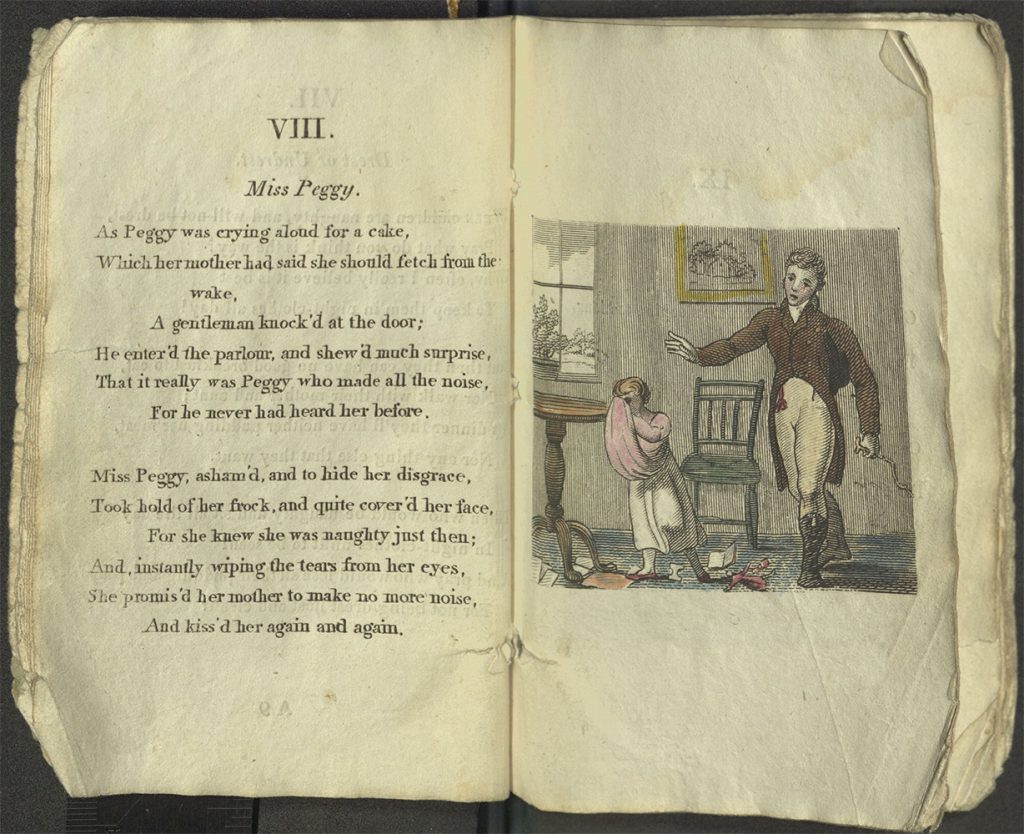

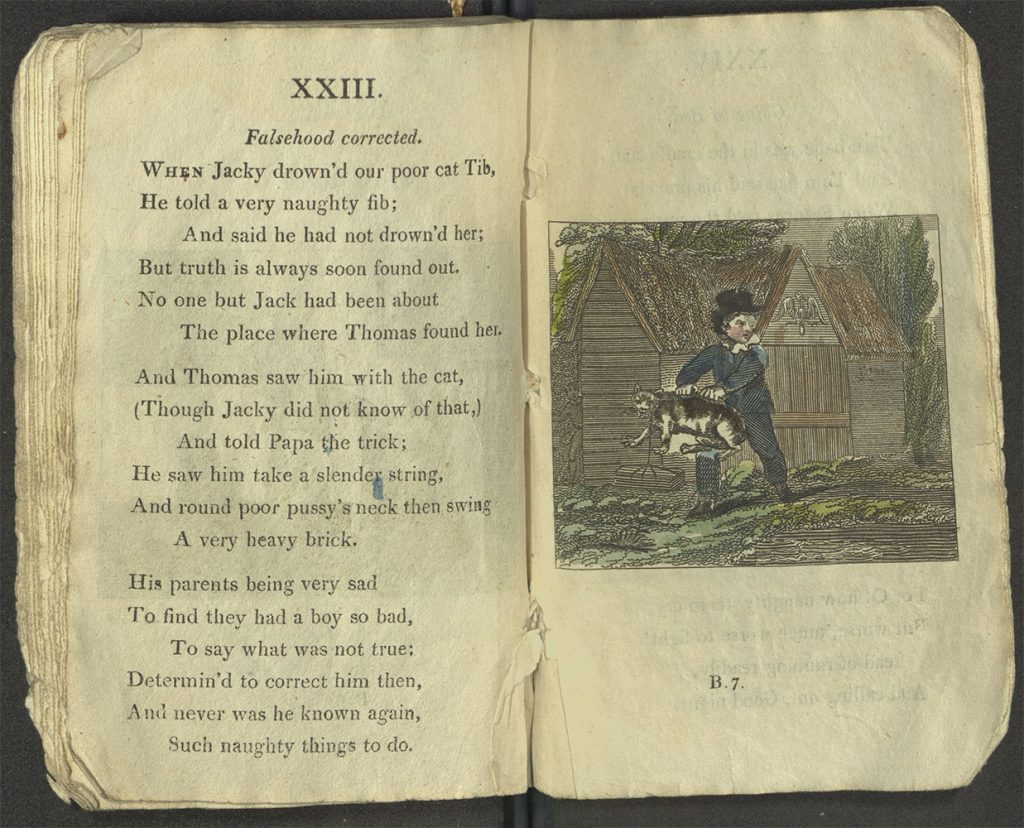

Social pressure is another familiar motive for moral improvement. Miss Peggy is reformed from throwing tantrums by the humiliation of having a gentleman come into the house to learn what all the screaming is about.  We are not, of course, always sympathetic to 19th-century sensibilities. In “Falsehood Corrected” Jacky ties a brick to the cat and drowns it. But he is punished for lying about it – and not for having murdered the family pet.

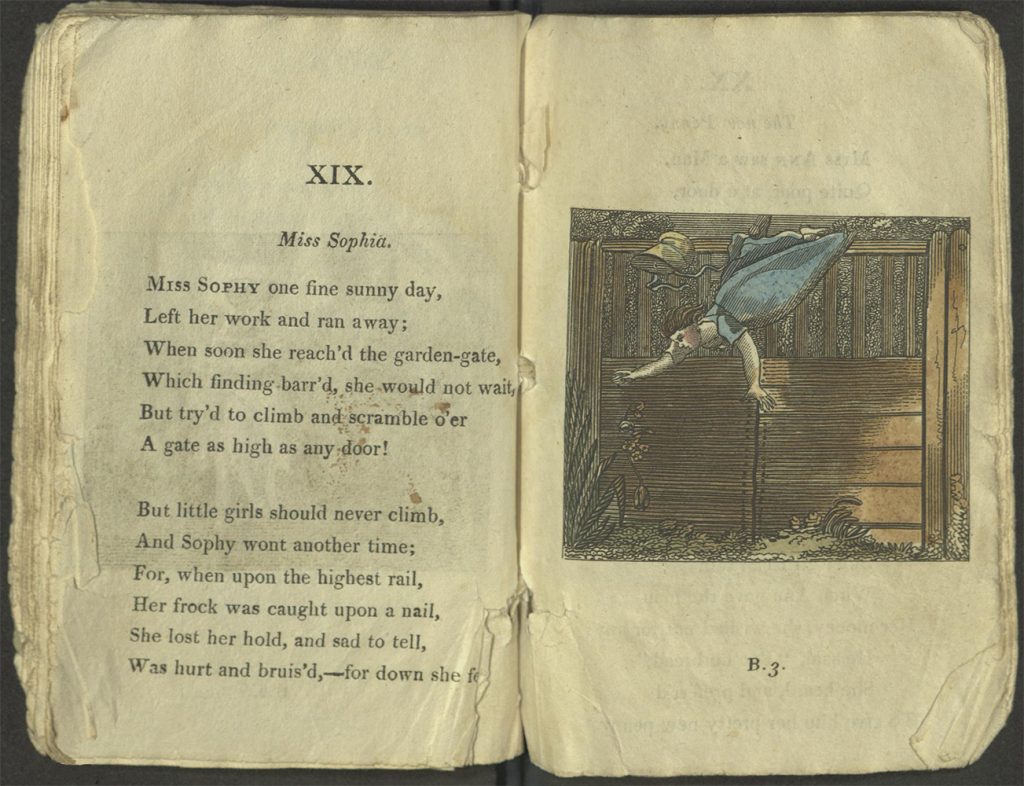

We are not, of course, always sympathetic to 19th-century sensibilities. In “Falsehood Corrected” Jacky ties a brick to the cat and drowns it. But he is punished for lying about it – and not for having murdered the family pet.  Strangest to us are the childish infractions which result in serious injury or death. Miss Sophia neglects her schoolwork and climbs a gate she knows she shouldn’t – and is injured in falling from a gate “as high as any door.”

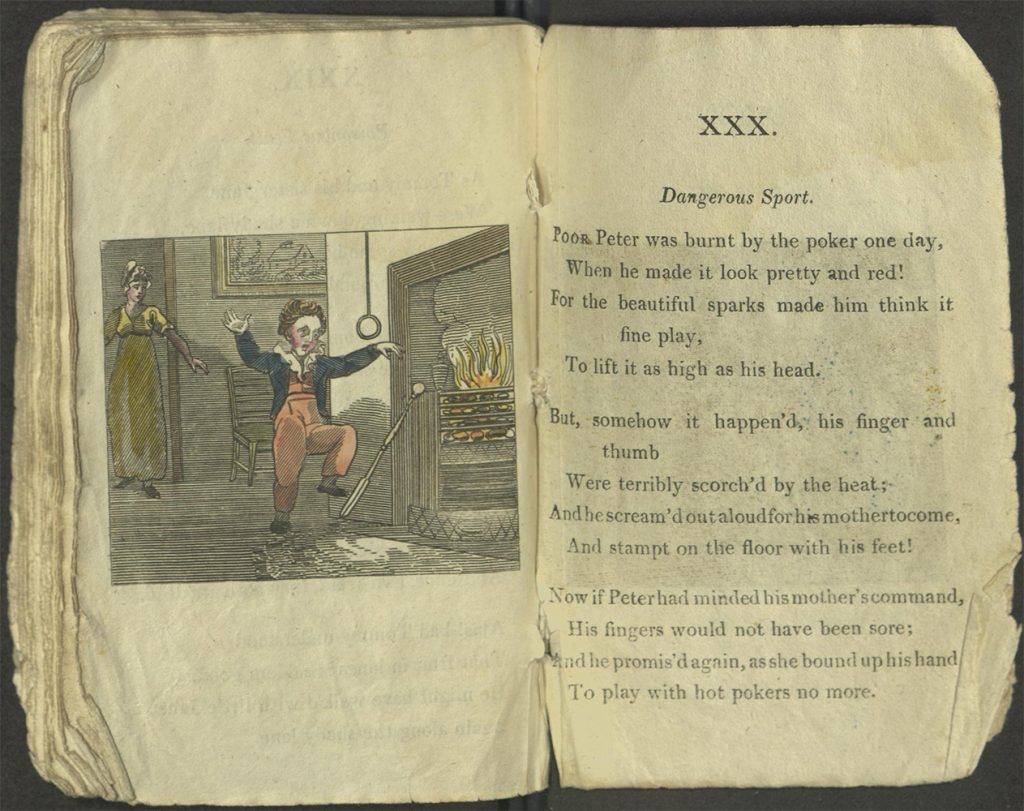

Strangest to us are the childish infractions which result in serious injury or death. Miss Sophia neglects her schoolwork and climbs a gate she knows she shouldn’t – and is injured in falling from a gate “as high as any door.”  Meanwhile, Peter warmed a fireplace poker to red heat, and waved it around until he burned himself – but he would not have been injured if he had obeyed his mother. Disobedience is the greatest, and underlying, offense in most of these stories. Besides recording actions that are inconsiderate, bad-tempered, or foolhardy, the poems stress that the children are doing what they had expressly been told not to do. Even “modern” 19th-century parents, who sympathized, and empathized, and relied upon discussion and reason in correcting their children, felt that those children should obey them immediately and without question.

Meanwhile, Peter warmed a fireplace poker to red heat, and waved it around until he burned himself – but he would not have been injured if he had obeyed his mother. Disobedience is the greatest, and underlying, offense in most of these stories. Besides recording actions that are inconsiderate, bad-tempered, or foolhardy, the poems stress that the children are doing what they had expressly been told not to do. Even “modern” 19th-century parents, who sympathized, and empathized, and relied upon discussion and reason in correcting their children, felt that those children should obey them immediately and without question.  As the the result of disobedience, three children in The Daisy are injured – Peter (burned), Sophia (bruised), and Frances, who spins until she is dizzy and hurts herself when she falls. Three die. The fatalities are Tom and Jane, who eat poisonous berries they should have left alone, and Helen, who looks into a well every chance she gets until the day she slips and falls in.

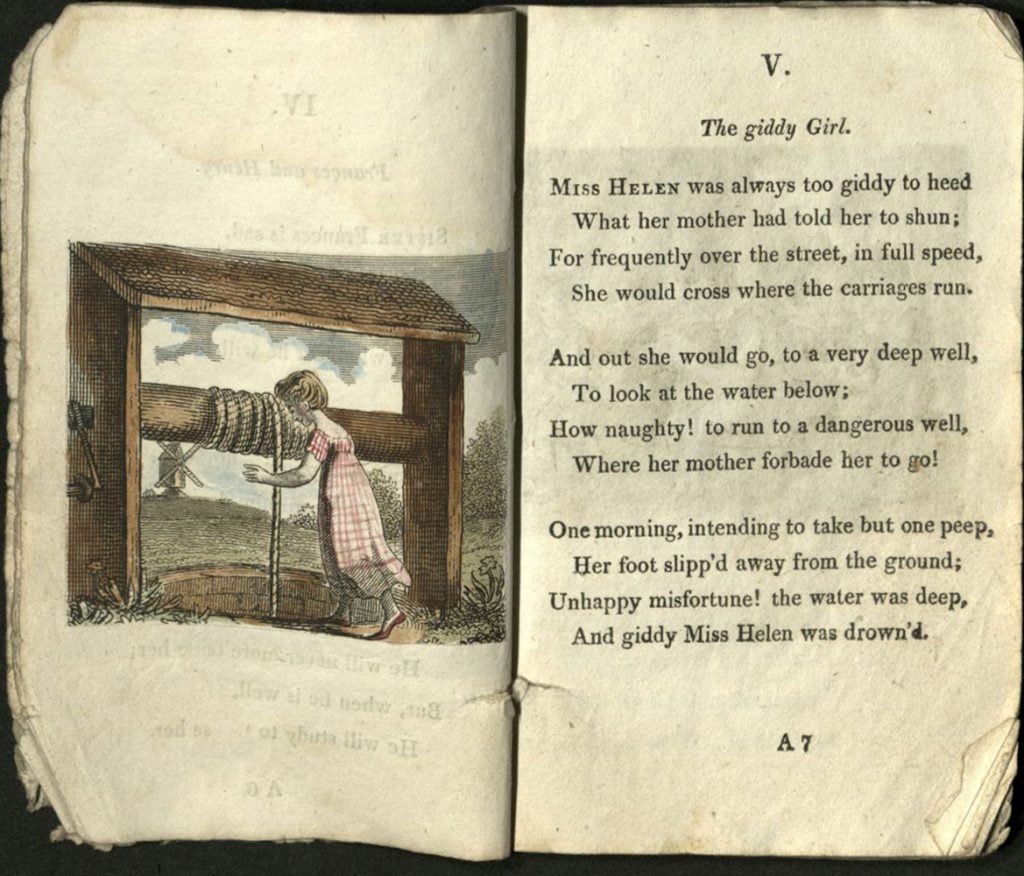

As the the result of disobedience, three children in The Daisy are injured – Peter (burned), Sophia (bruised), and Frances, who spins until she is dizzy and hurts herself when she falls. Three die. The fatalities are Tom and Jane, who eat poisonous berries they should have left alone, and Helen, who looks into a well every chance she gets until the day she slips and falls in.  Helen also used to run across the street, disregarding the danger of carriages. And this gives us a hint that there might actually have been something reasonable about the urgency that drove Elizabeth Turner and contemporary writers to condemn so harshly what seems like simple disobedience and childish foolishness.

Helen also used to run across the street, disregarding the danger of carriages. And this gives us a hint that there might actually have been something reasonable about the urgency that drove Elizabeth Turner and contemporary writers to condemn so harshly what seems like simple disobedience and childish foolishness.

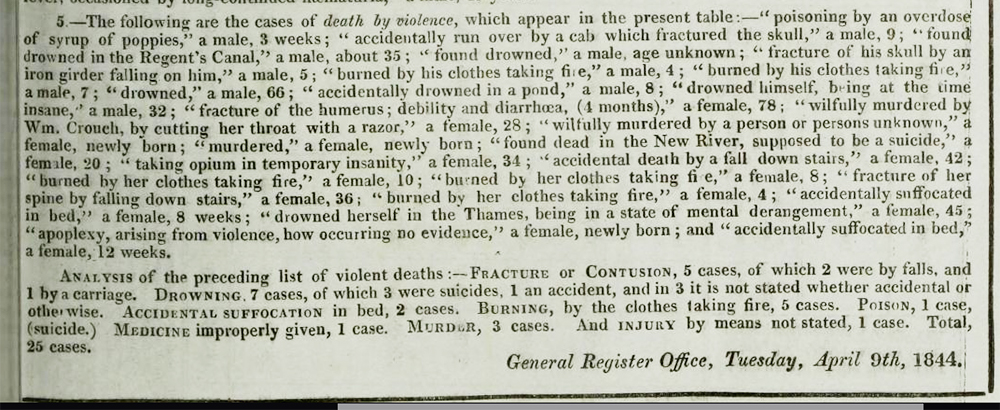

General Register Office; Royal College of Physicians of London. A Table of Mortality for the Metropolis, Shewing the Number of Deaths from All Causes Registered in the Week ending Saturday, 6th April. London: Hartnell, 1844. Scan from the Internet Archive.

The General Register Office for England and Wales, in 1844, began publishing reports for deaths in London in a format that permits one to track causes of mortality for children. I took a quick sample – the first week of each month from that year. Of the 5350 persons between the ages of 0 and 15 who died in those twelve weeks, 102 suffered “Violent deaths” – something other than disease or an inherent medical condition killed them. 40 of those deaths resulted from the children’s clothes catching fire (and 2 more were scalded). Thirteen of the young people drowned. Eleven were run over by carriages. Five fell to their deaths. Nearly 70% of these real children died of one of the causes through which the imaginary children in The Daisy endanger themselves.

I finished my short statistical foray with new sympathy for the “dreadful results” genre of moral literature for the young. It still sounds shrill to me. But I have more specific, evidence-based, ideas now about the perils of living in a time when people cooked with fire, drove horses at high speed through crowded streets, and maintained uncovered wells. The behaviors punished in the poems were demonstrably dangerous. One can hardly blame loving parents from trying what they might to keep their children from harm.

– Marianne Hansen, Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts

Turner, Elizabeth, and John Harris. The Daisy, or, Cautionary Stories in Verse: Adapted to the Ideas of Children from Four to Eight Years Old. London: J. Harris, 1807. We have not yet digitized our copy of The Daisy, but you can get an idea of the book from the 1817 edition at the University of California.

Explore the Table of Mortality for the Metropolis for yourself on the Internet Archive

With the continuing closure of the Library, we are blogging regularly about books from the exhibition, The Girl’s Own Book. Please subscribe or check back here, or follow us on Facebook for notices of new blog posts.

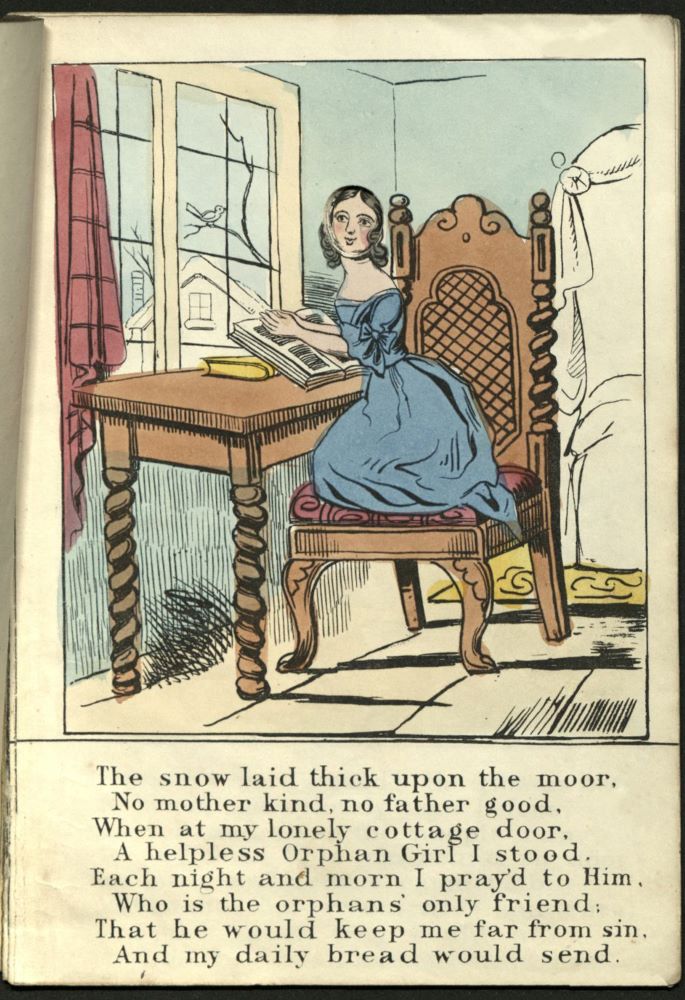

As a result of her earnest piety, her garden provides abundant bouquets which she sells to the wealthy.

As a result of her earnest piety, her garden provides abundant bouquets which she sells to the wealthy.