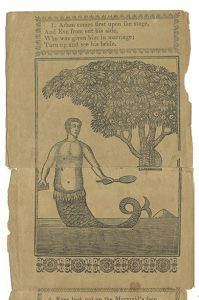

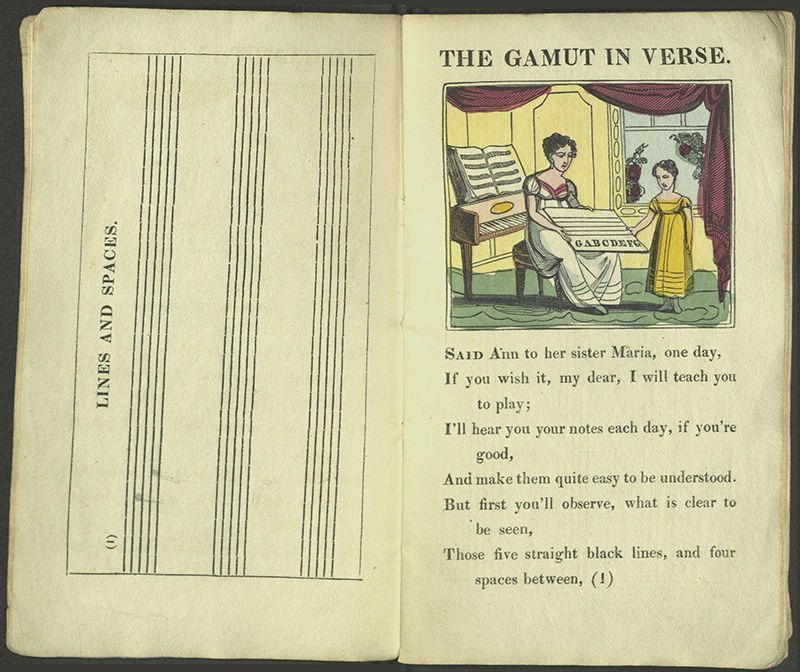

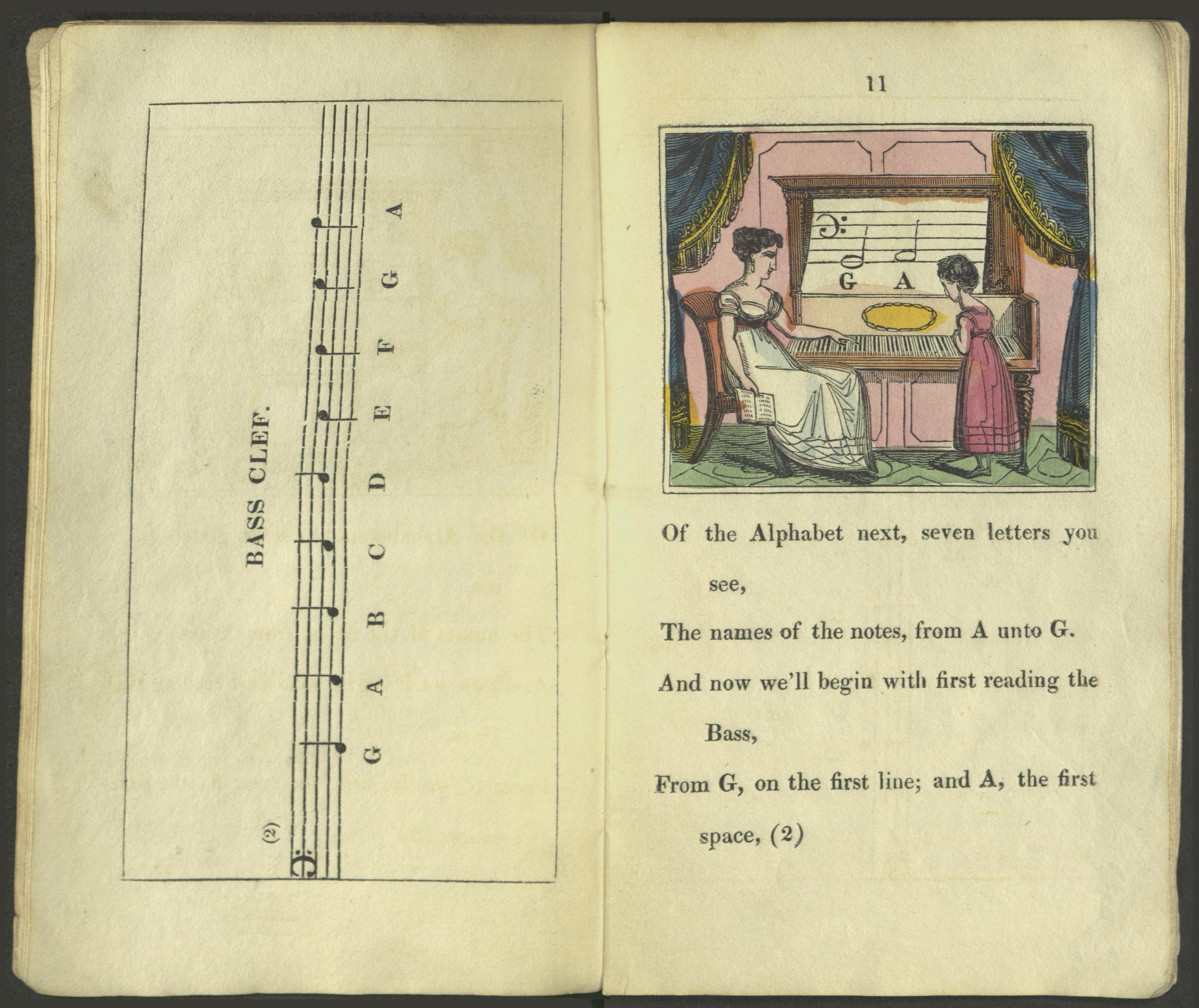

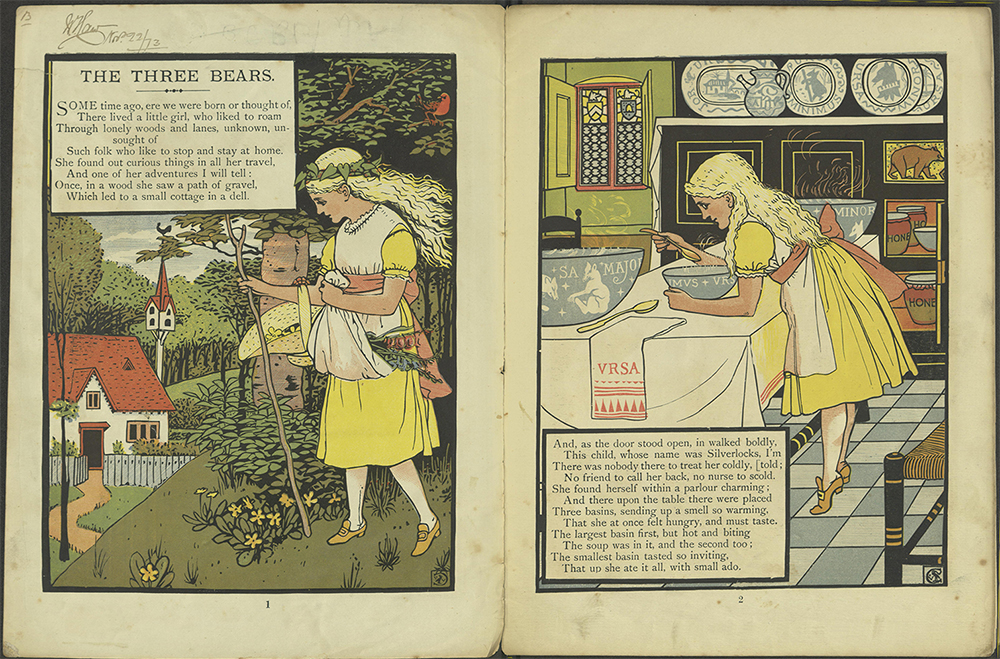

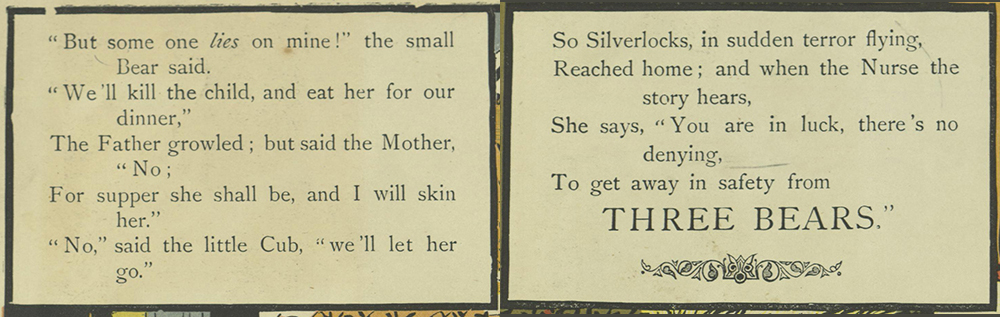

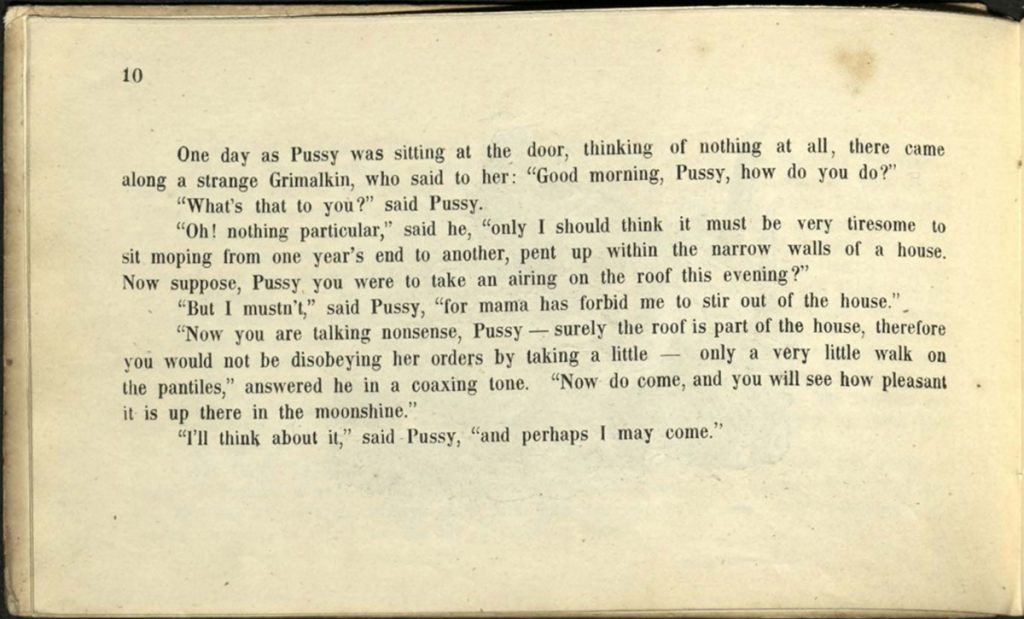

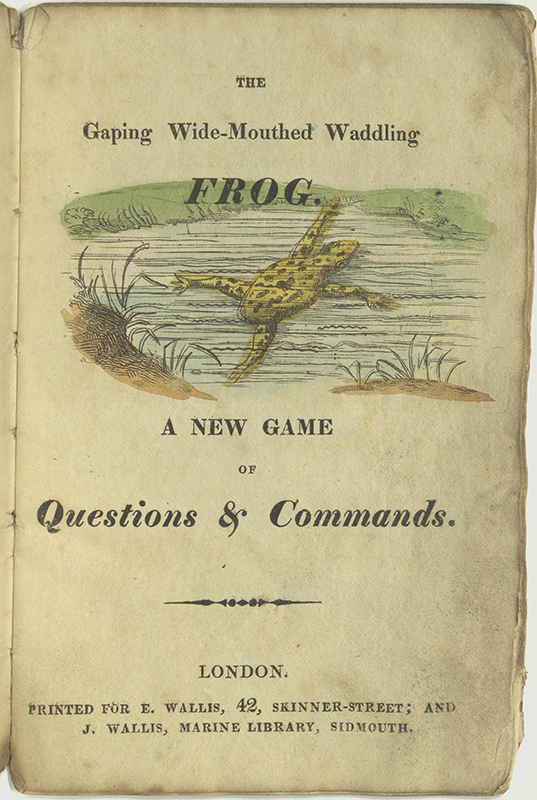

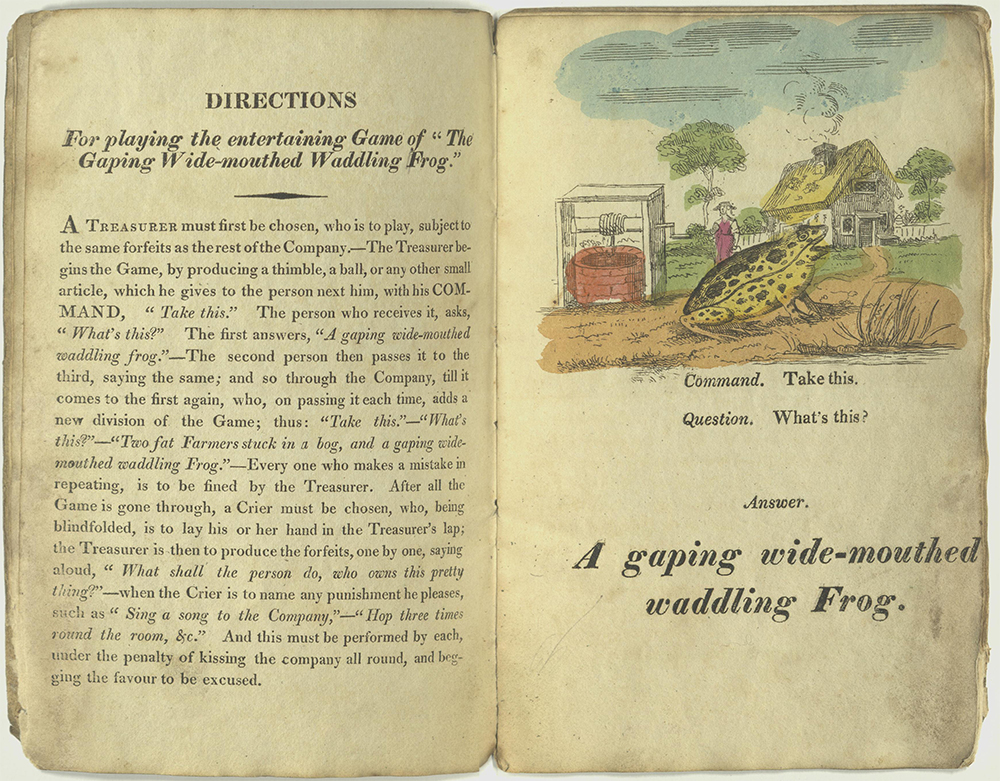

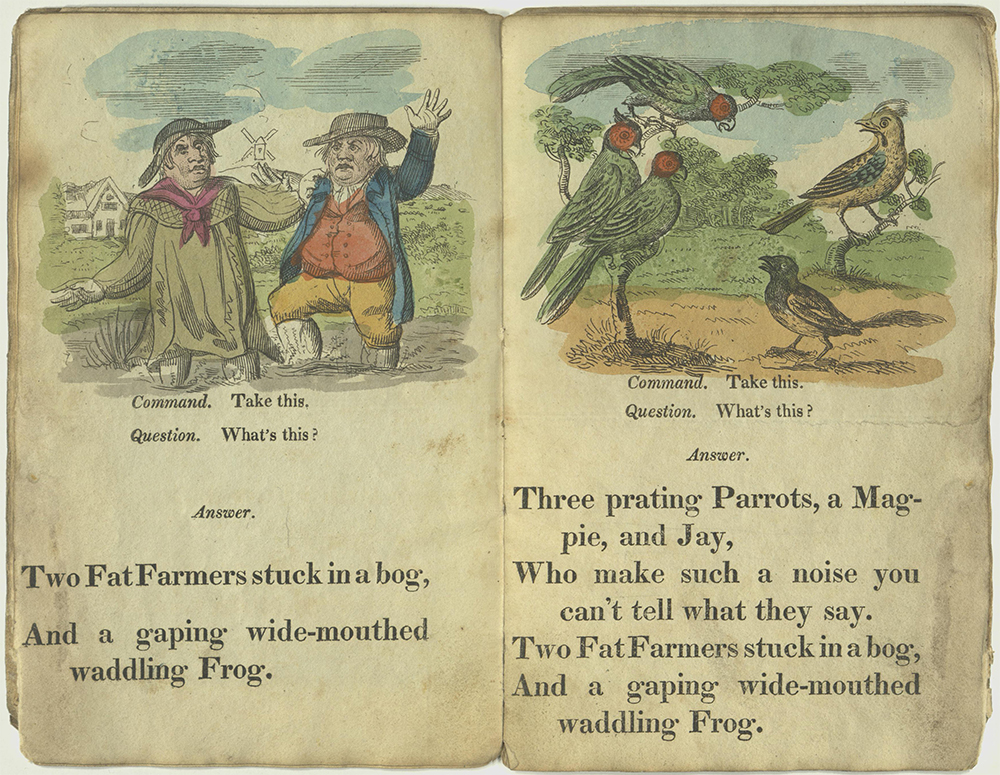

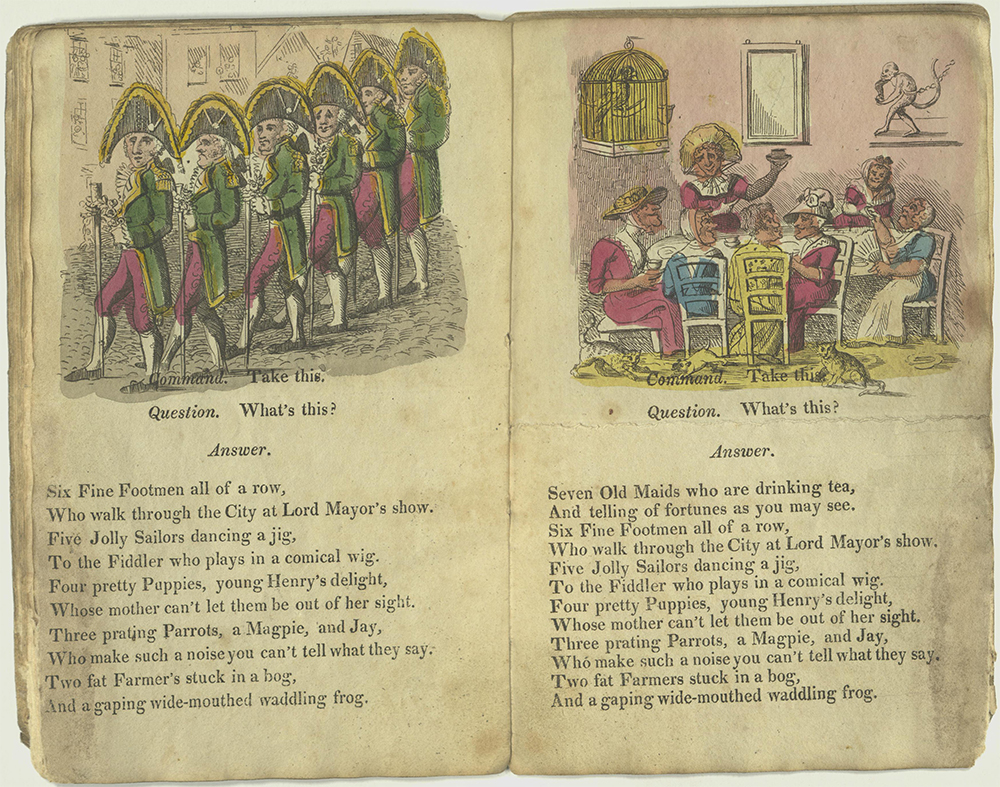

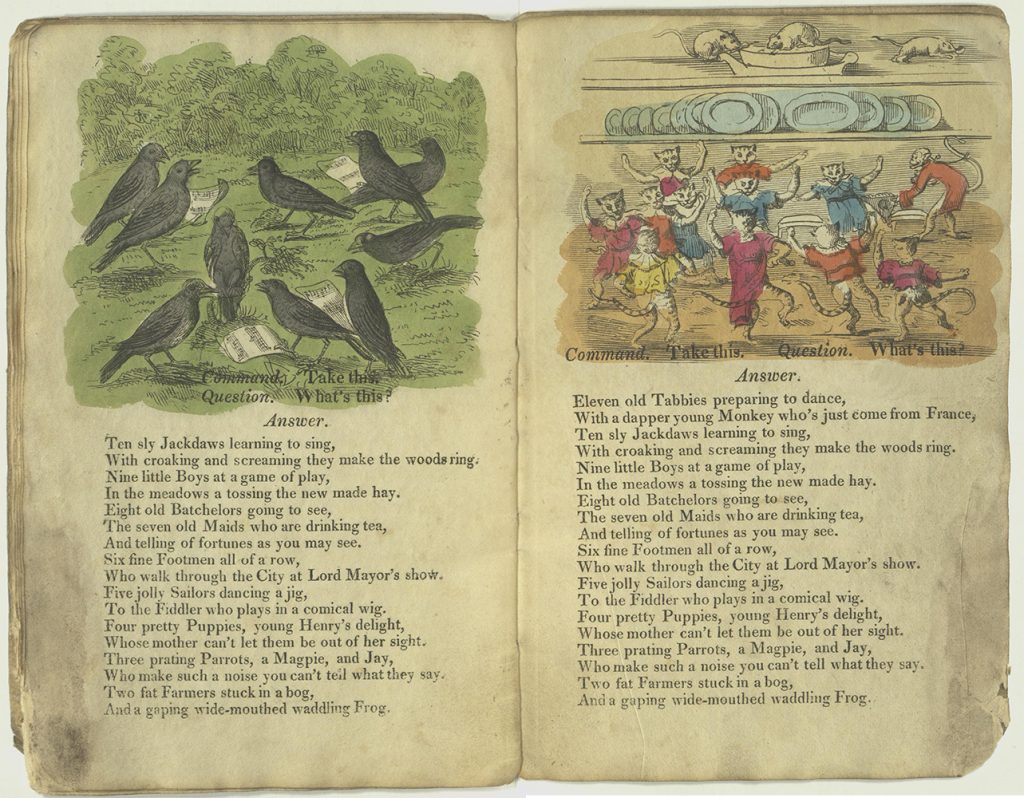

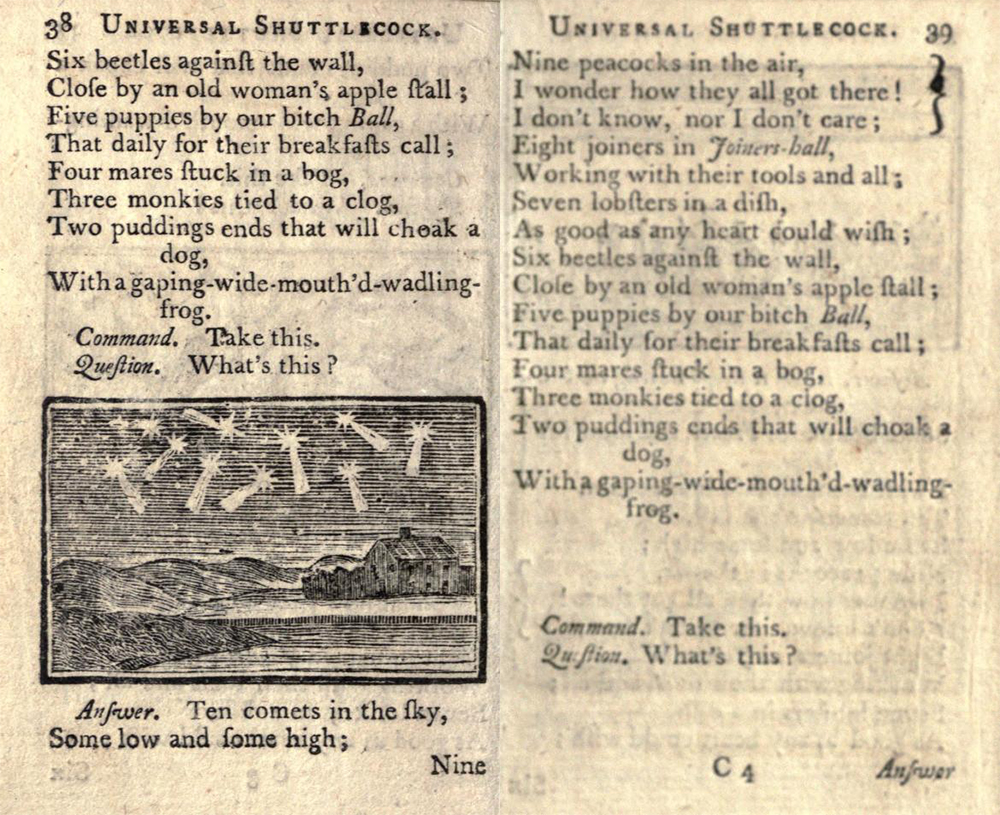

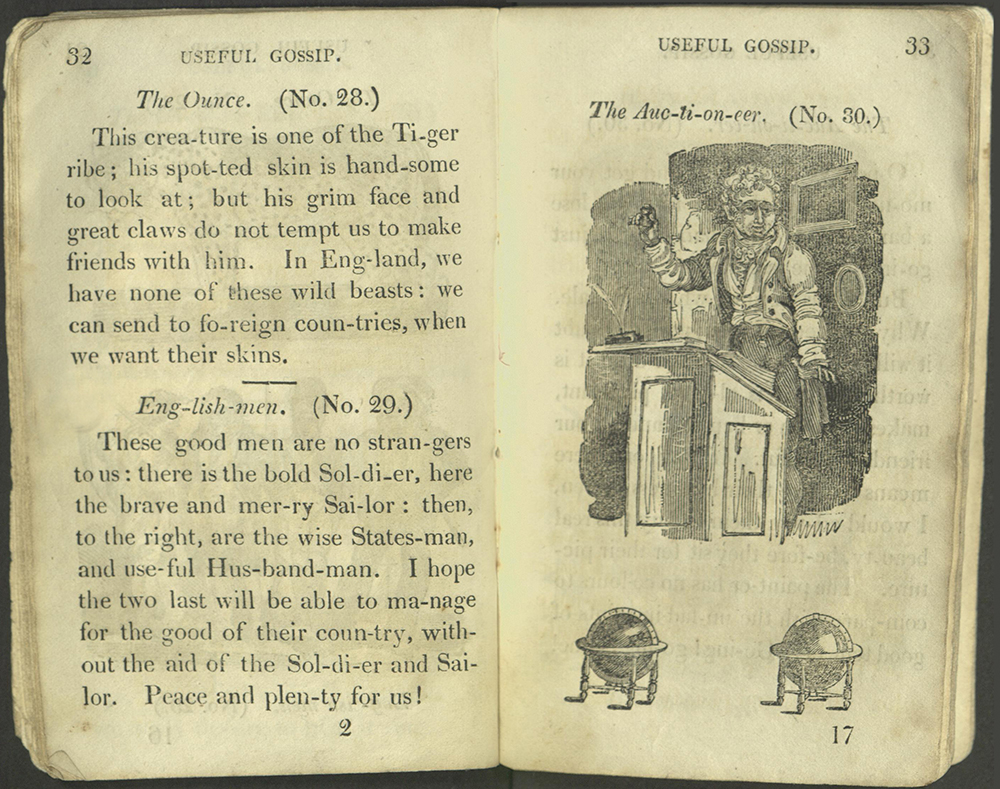

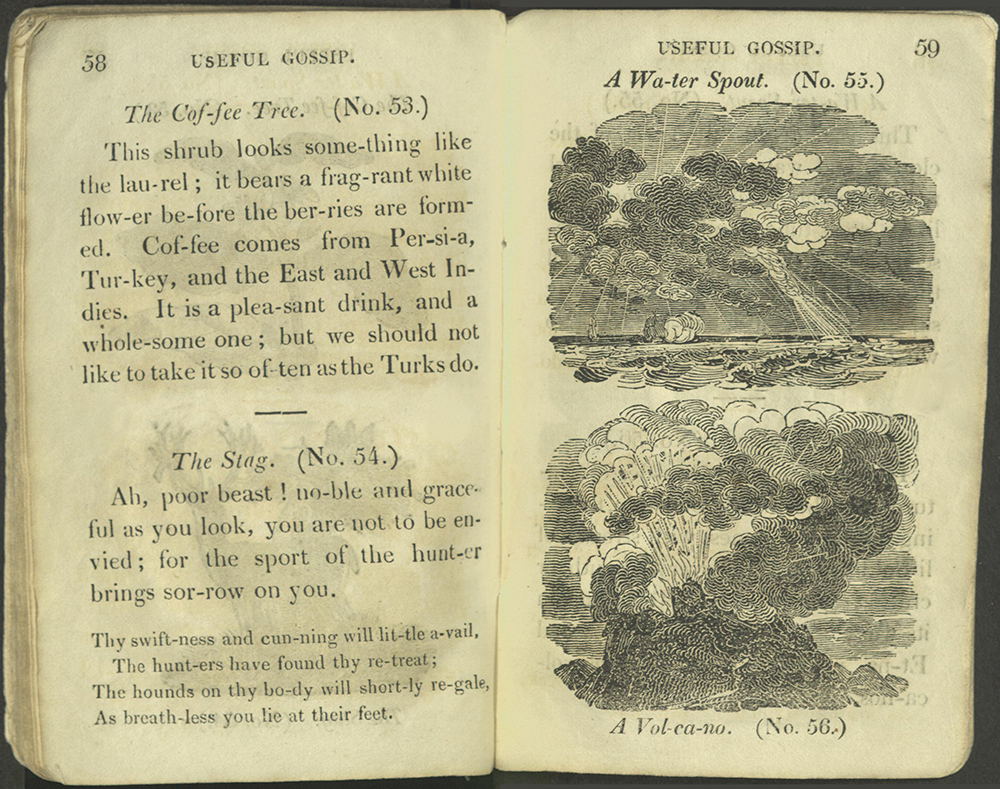

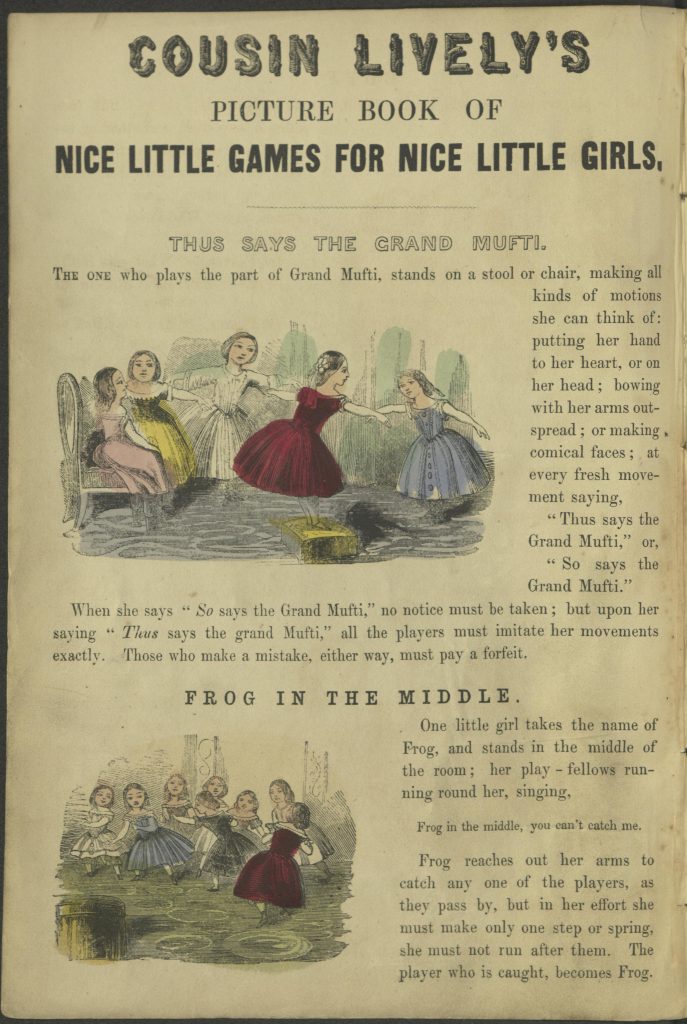

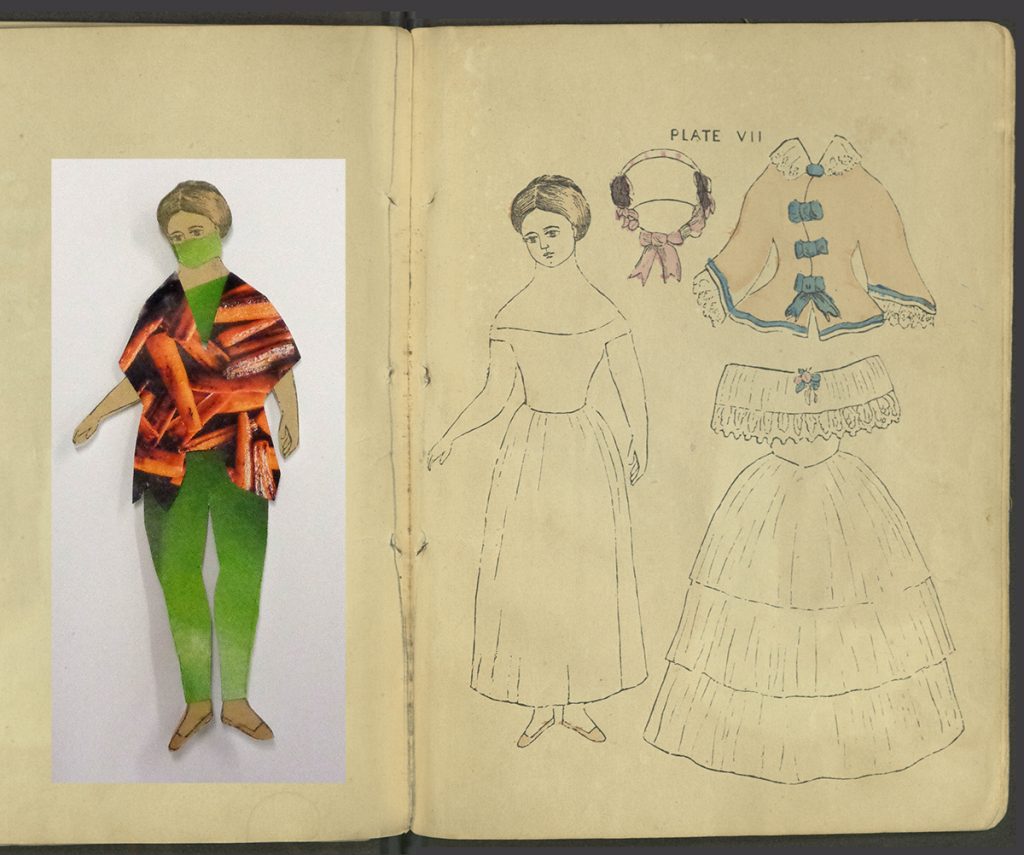

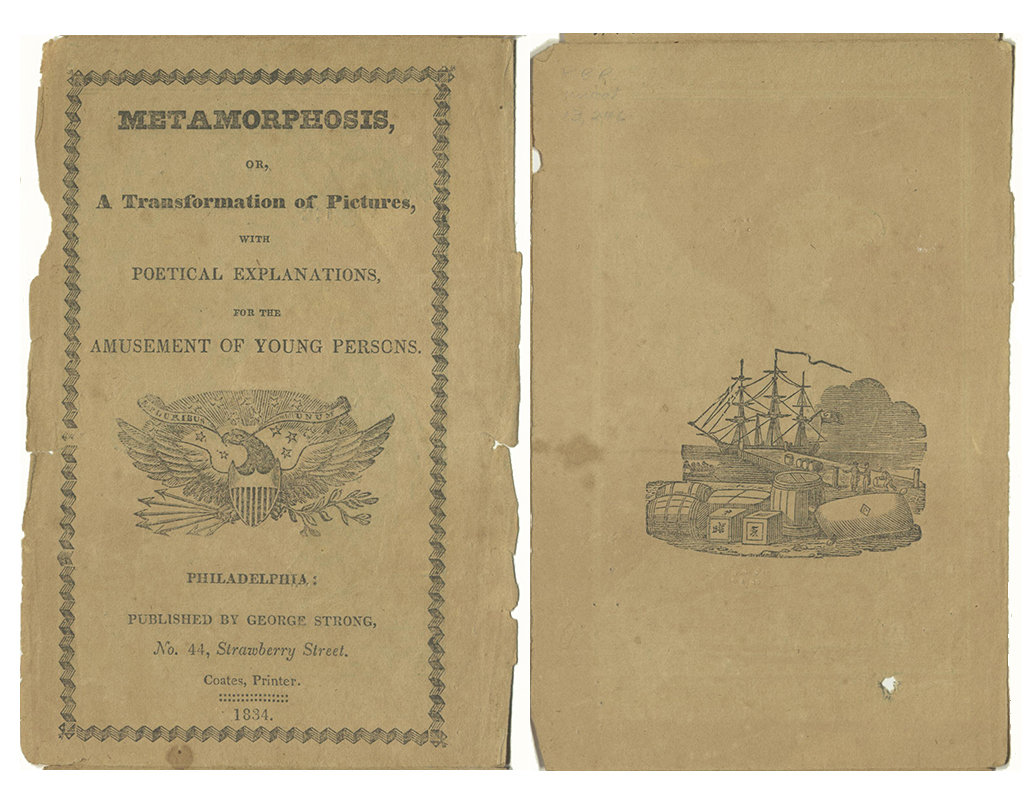

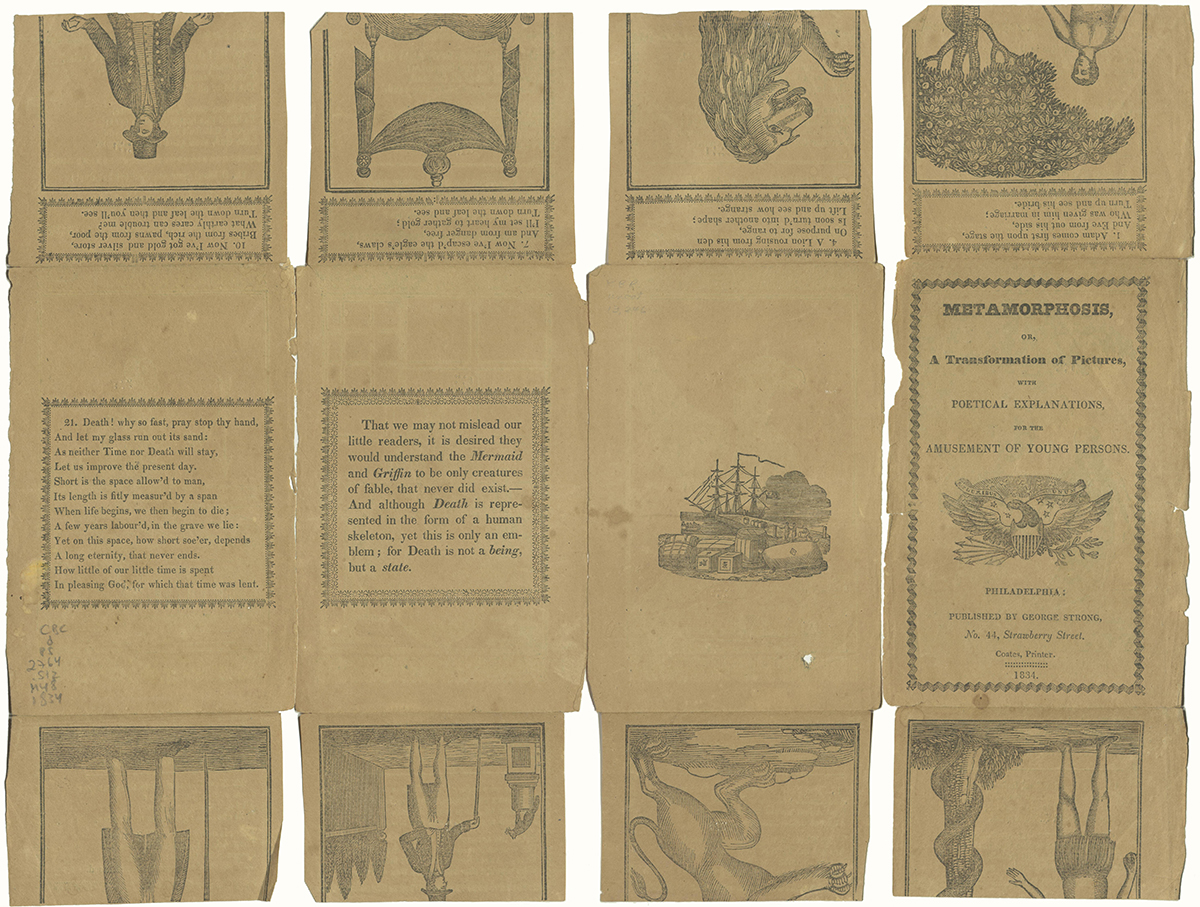

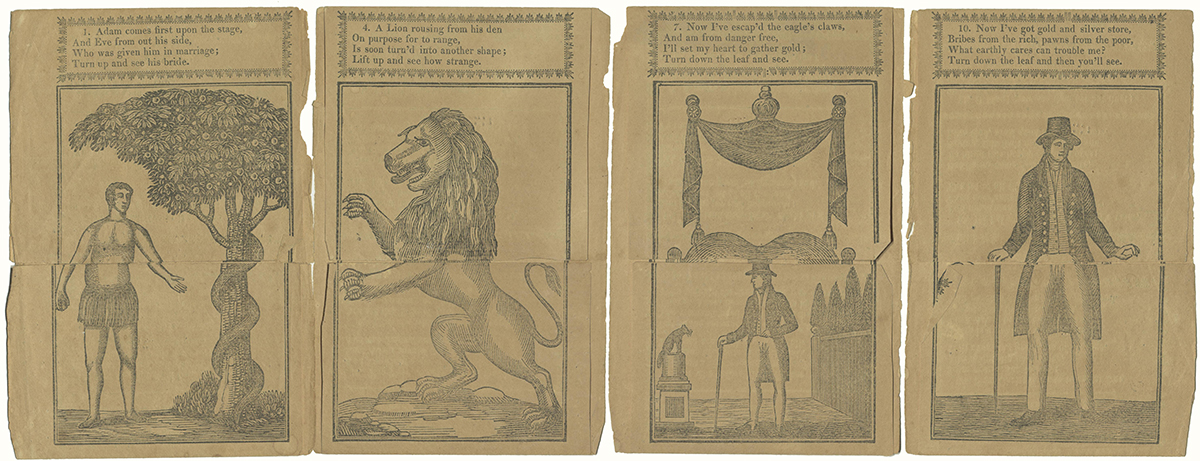

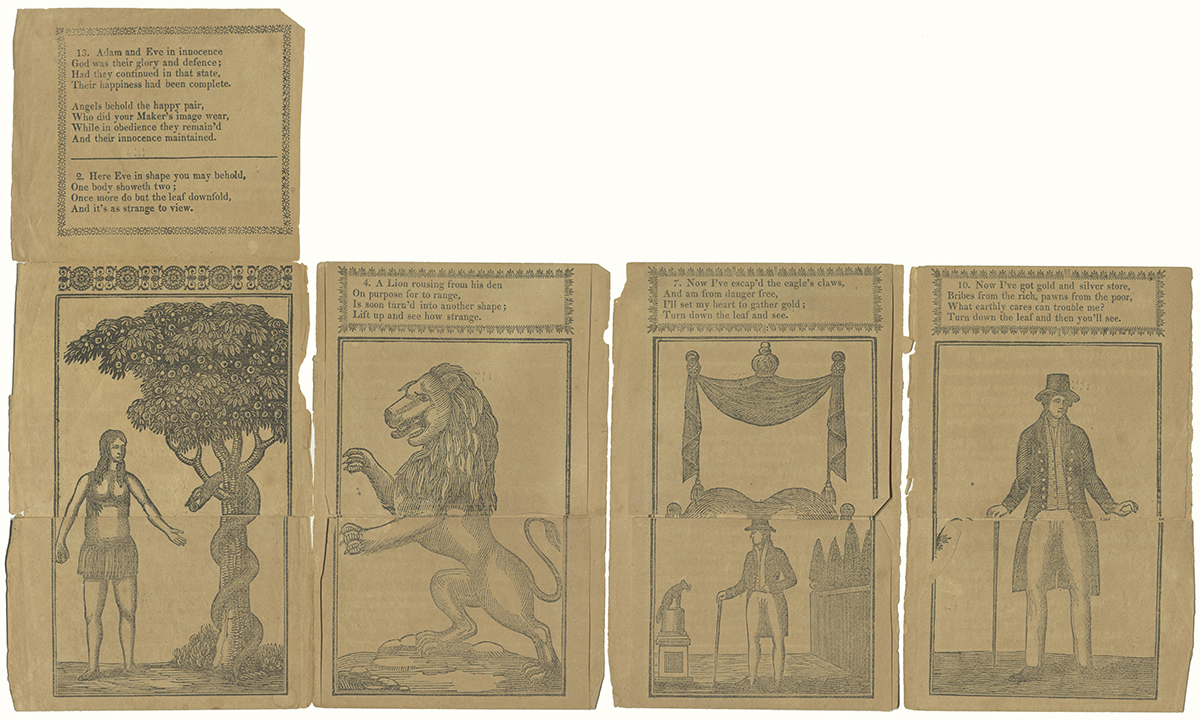

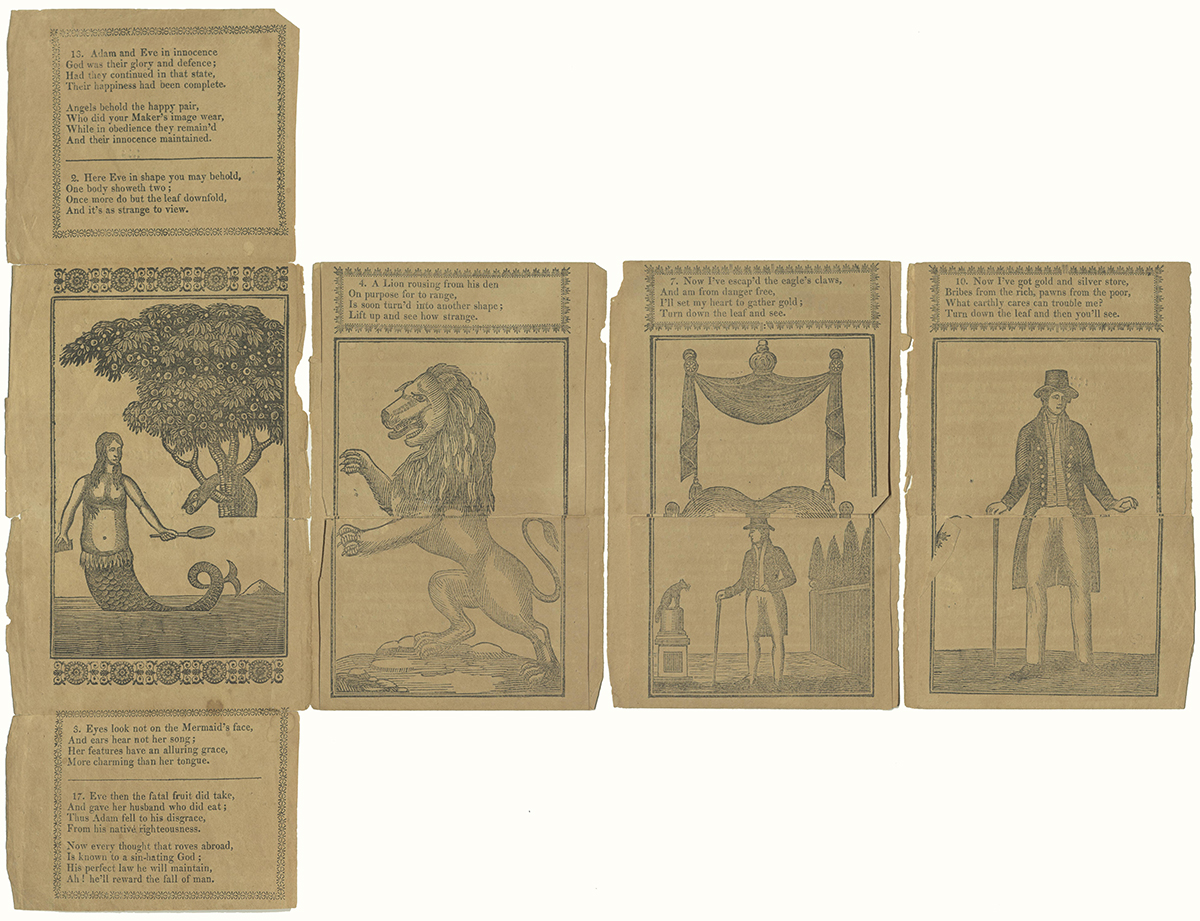

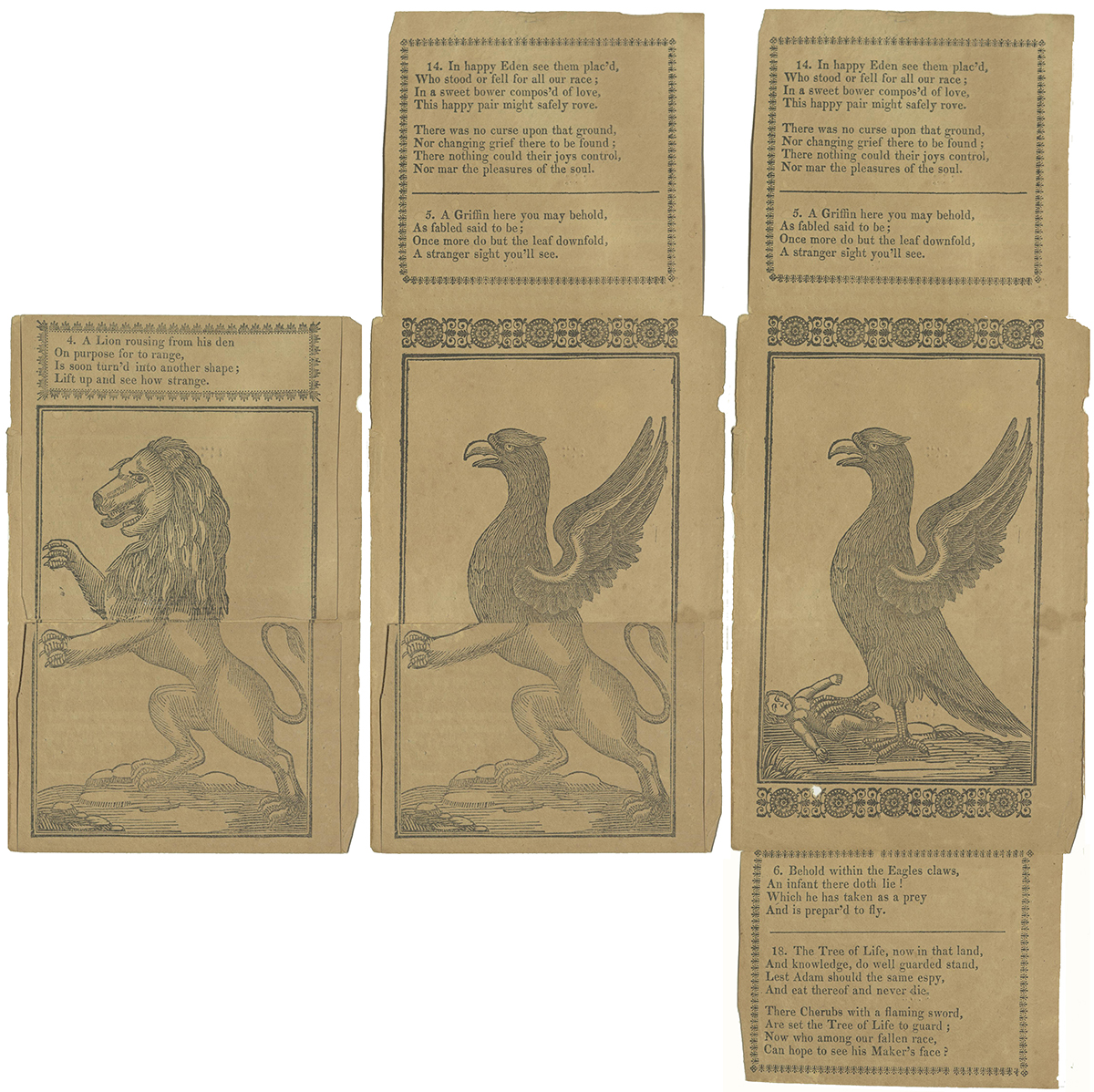

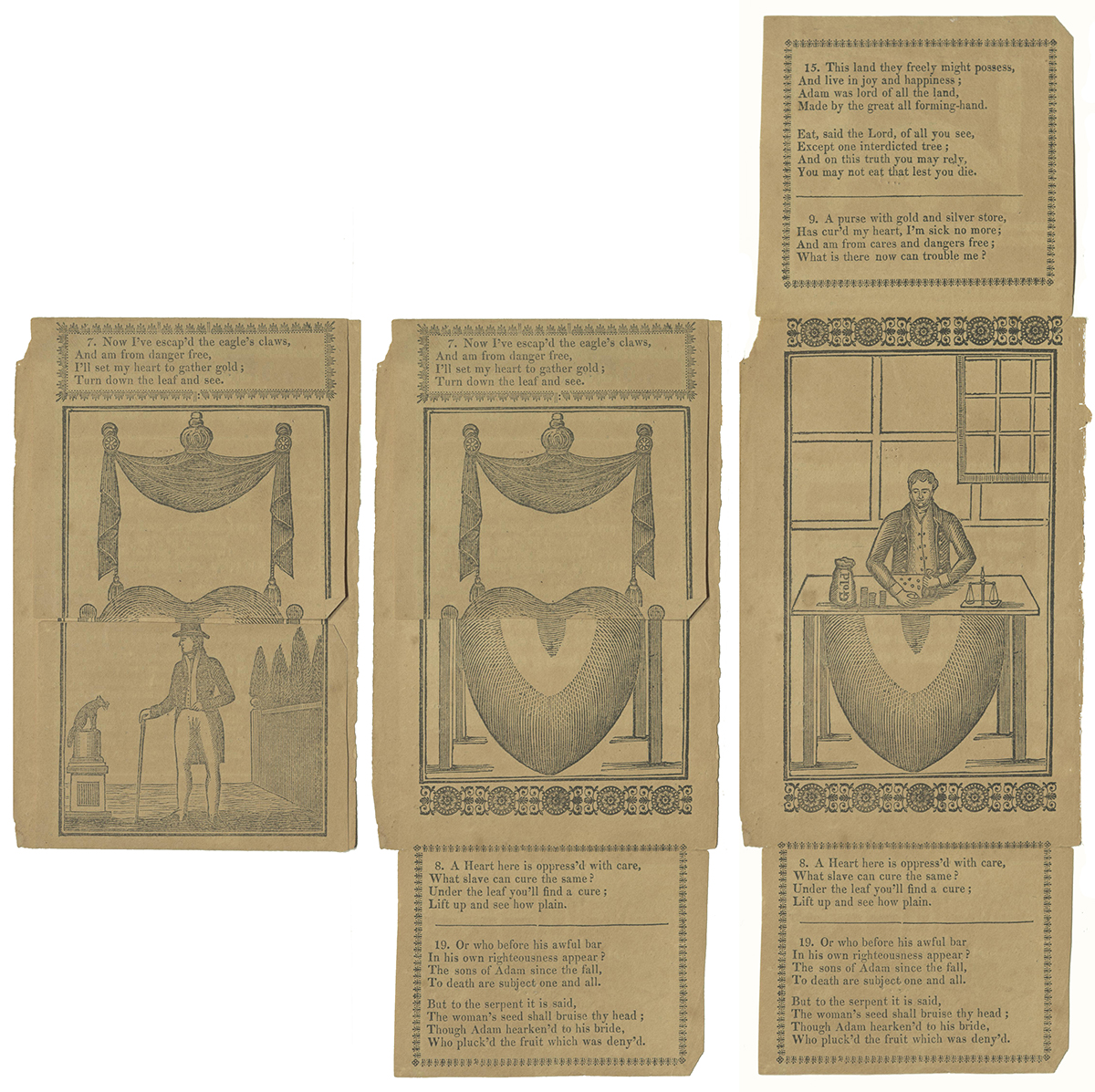

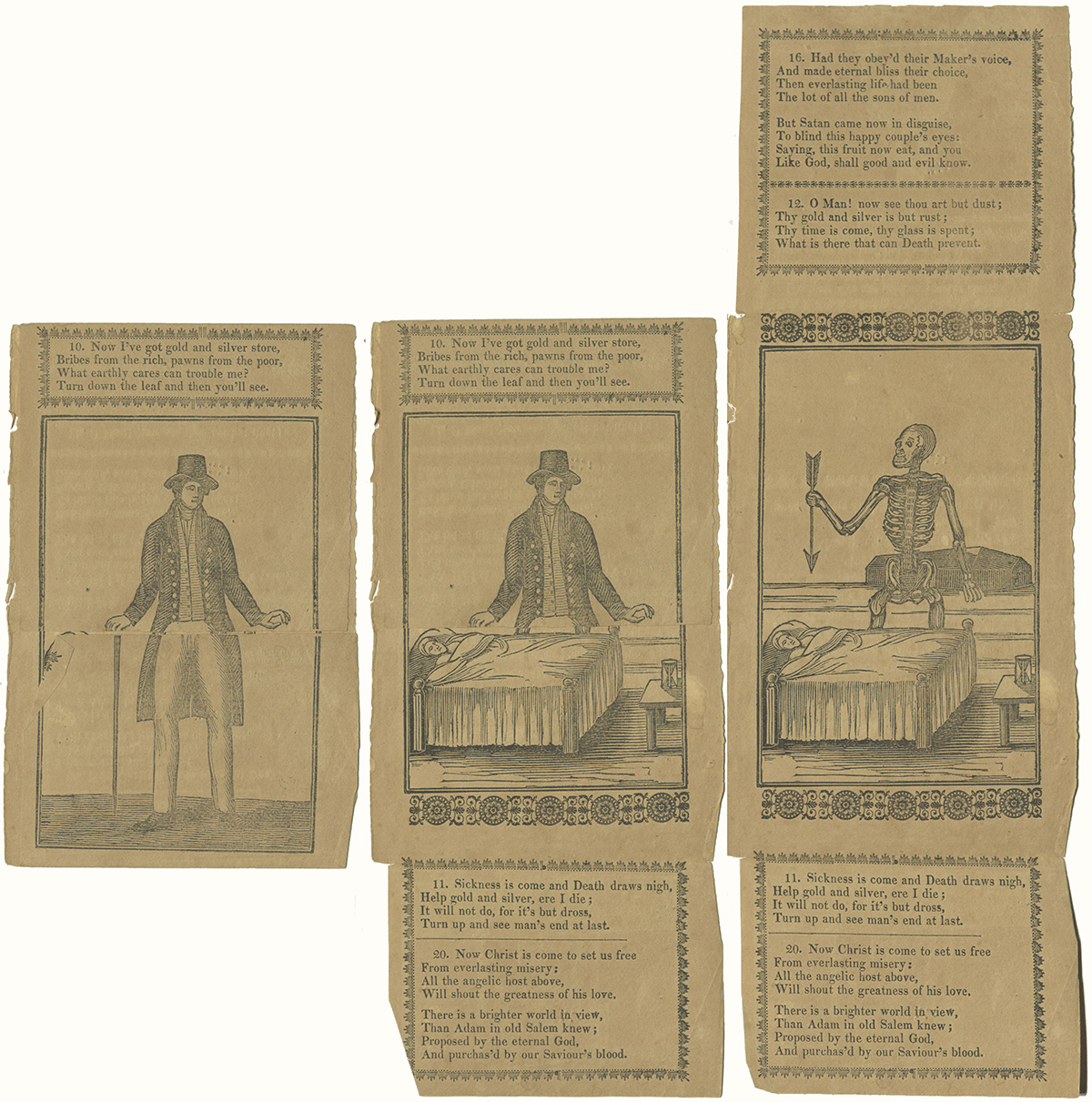

The text describing each image is printed on the back of the page, rather than the facing page, which is initially confusing. A scan of our copy is available on the Internet Archive – find the link at the bottom of the page.

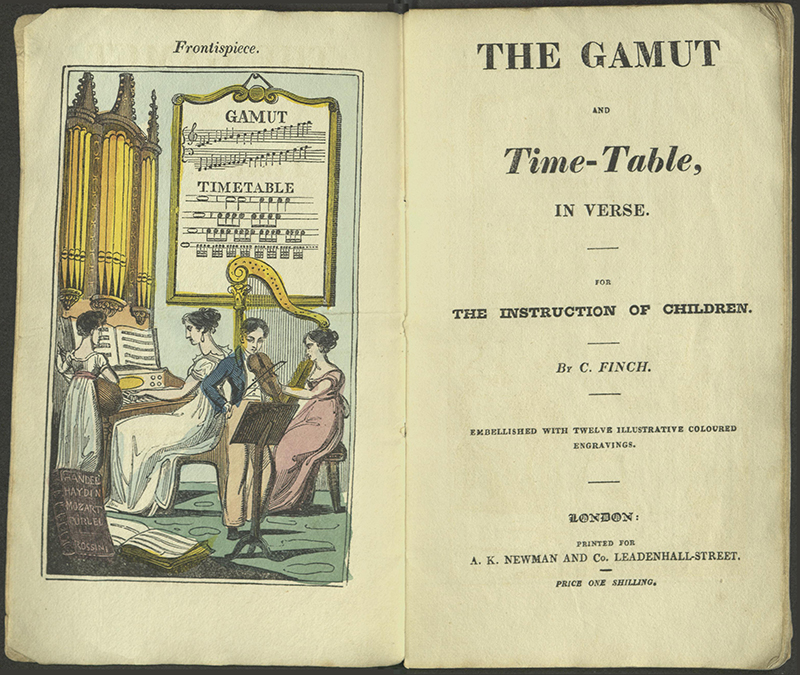

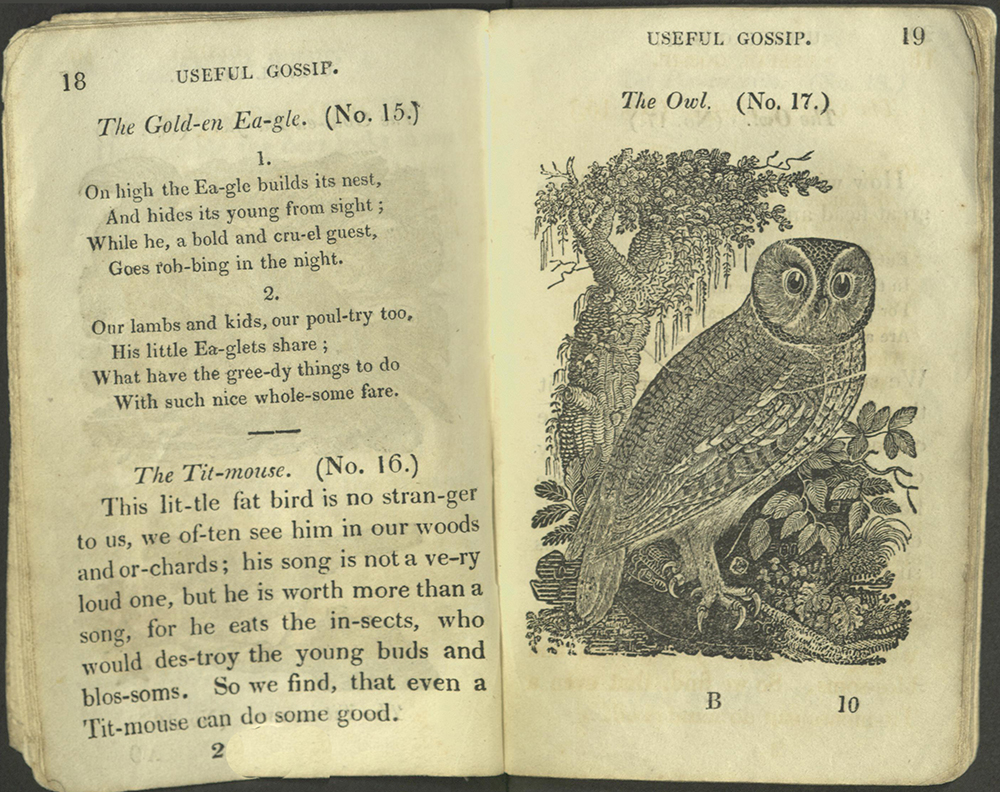

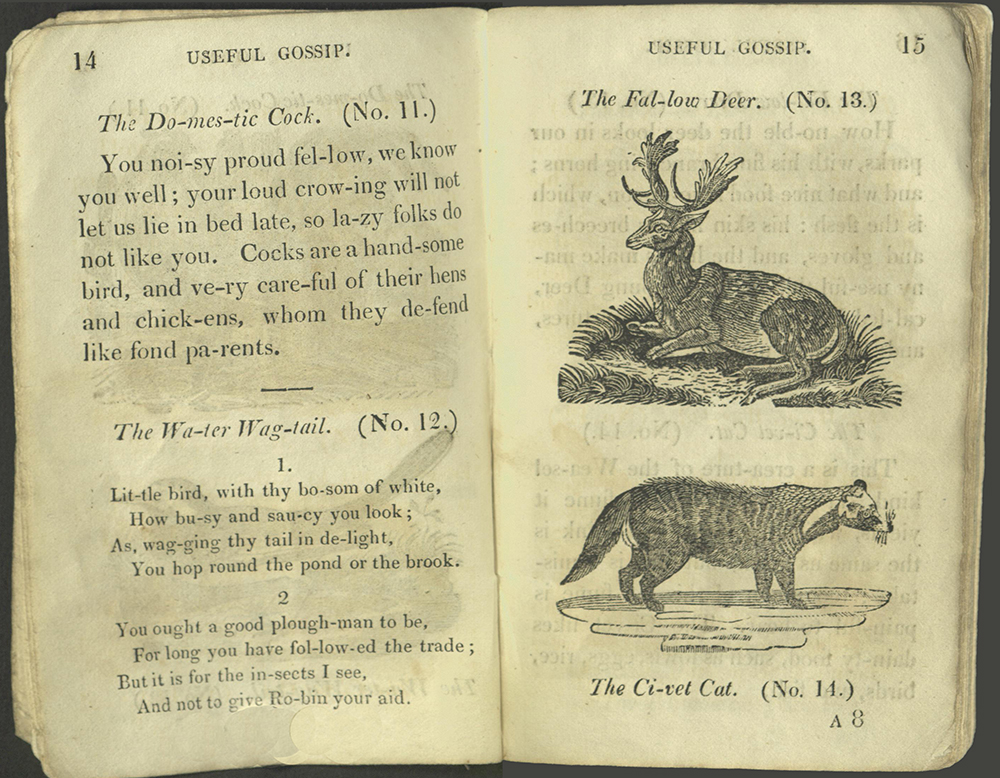

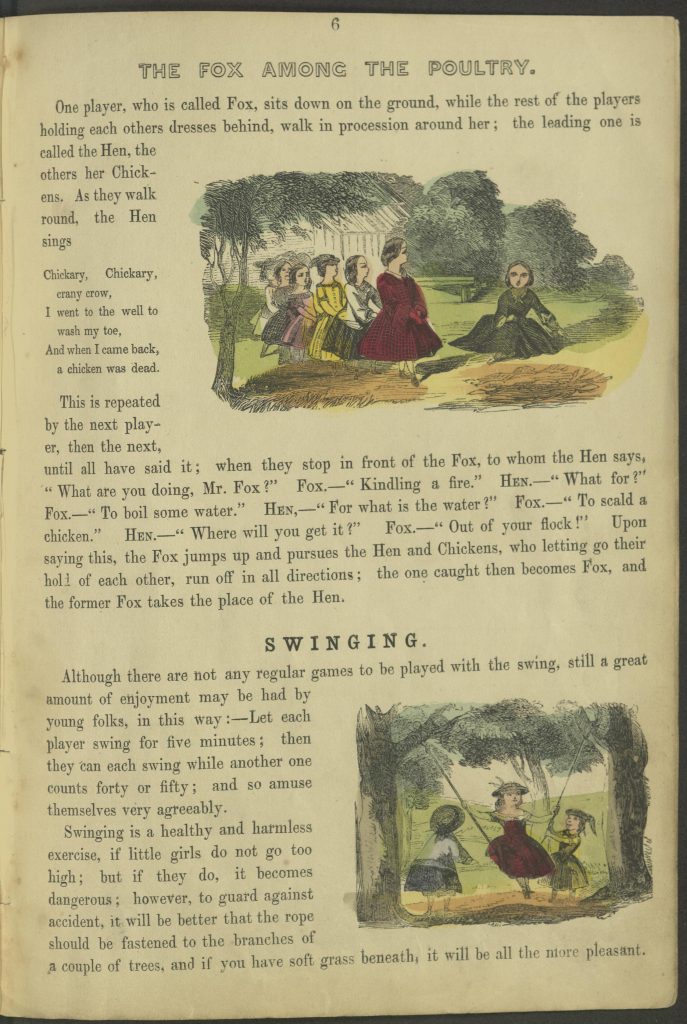

Children’s books are often illustrated, and a number of technological advances in printing during the 18th and 19th centuries led to an outpouring of stylish, beautiful, and sometimes brightly colored publications. The earliest of these innovations was wood engraving. The inventor of the technique is unknown, but it was extensively developed by the artist and printer Thomas Bewick beginning in the 1760s. Bewick’s work established the medium, and his workshop produced dozens of prominent engravers who had begun with him as apprentices.

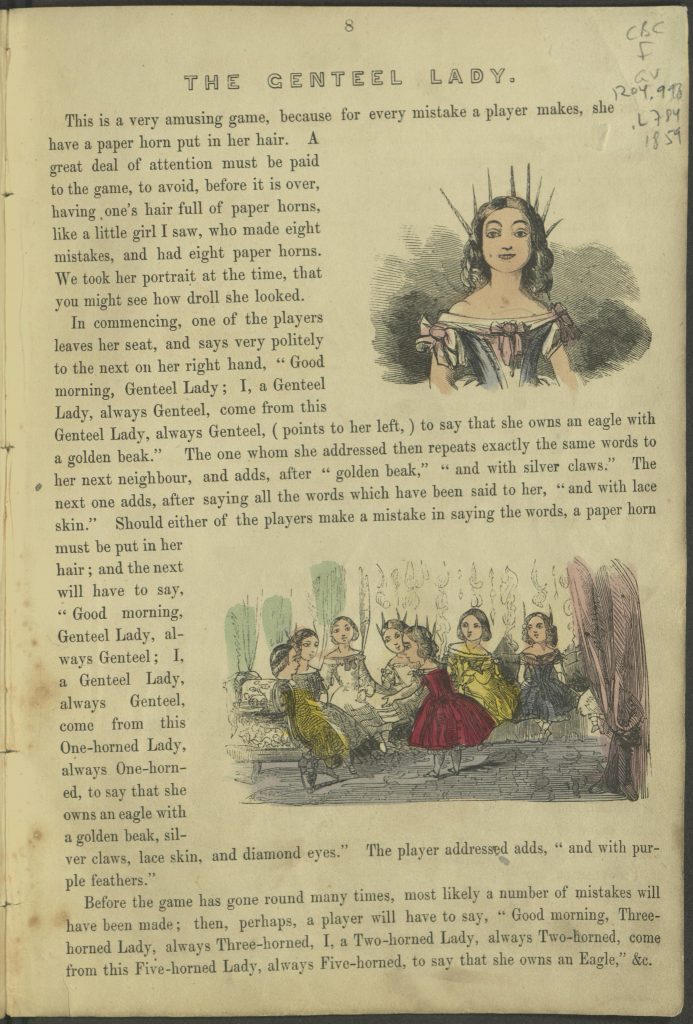

Wood engraving is a relief printing process: the ink is applied to those parts of the printing block which stick out – imagine a rubber stamp. (This contrasts with intaglio processes, where the ink is wiped into lines cut or etched into a plate, and must be lifted out by the paper, which is pressed very hard onto the plate and into the grooves.) Woodcuts, which were normally used for economical book illustration in Europe from the fifteenth century until wood engraving superseded them, are also relief prints. Both techniques use blocks that can be printed at the same time with movable type, set up in the same frames. This makes them easy, fast, and inexpensive to print and means that even ephemeral publications or books that must be printed very cheaply, like children’s books, can have a large number of illustrations. The blocks can be reused indefinitely, and may appear in more than one publication.

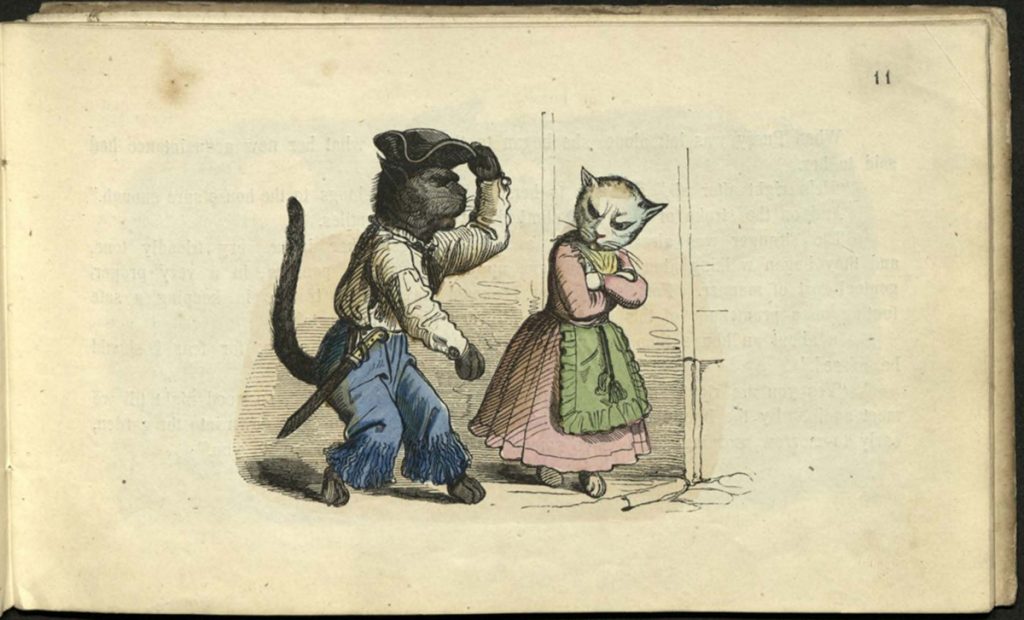

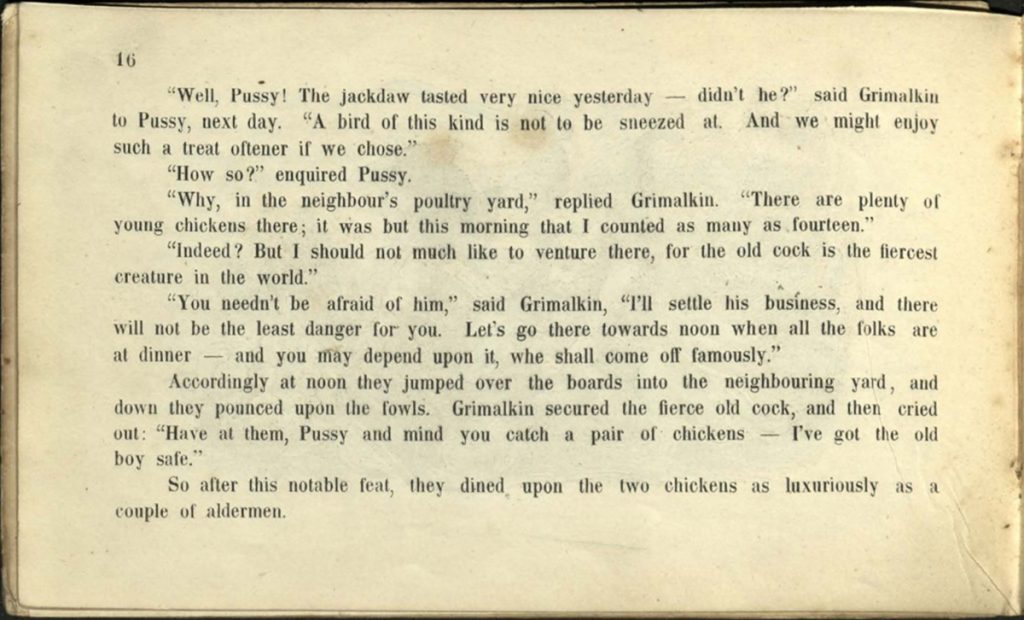

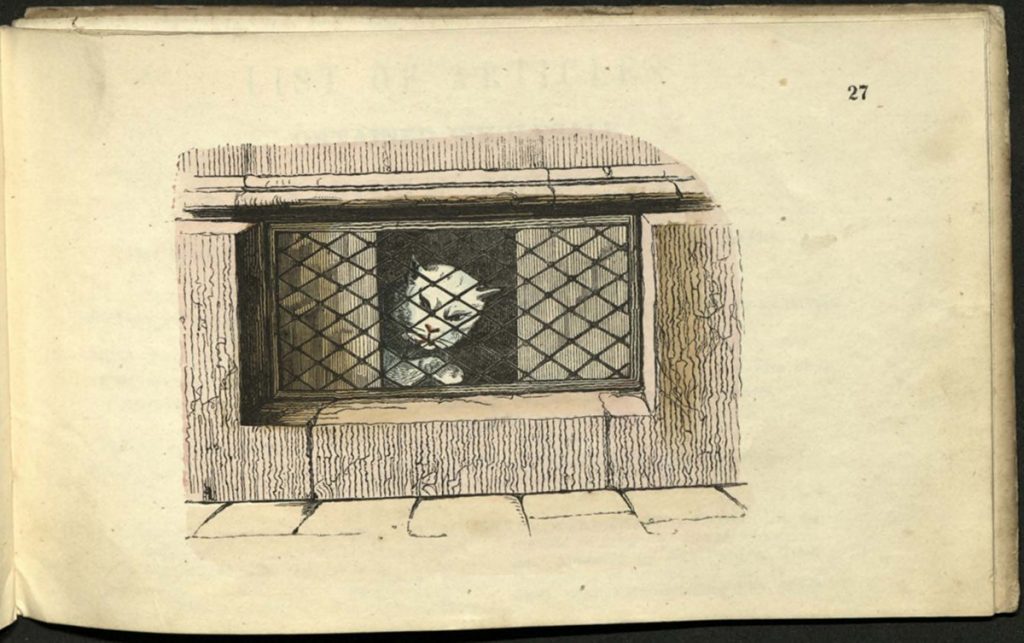

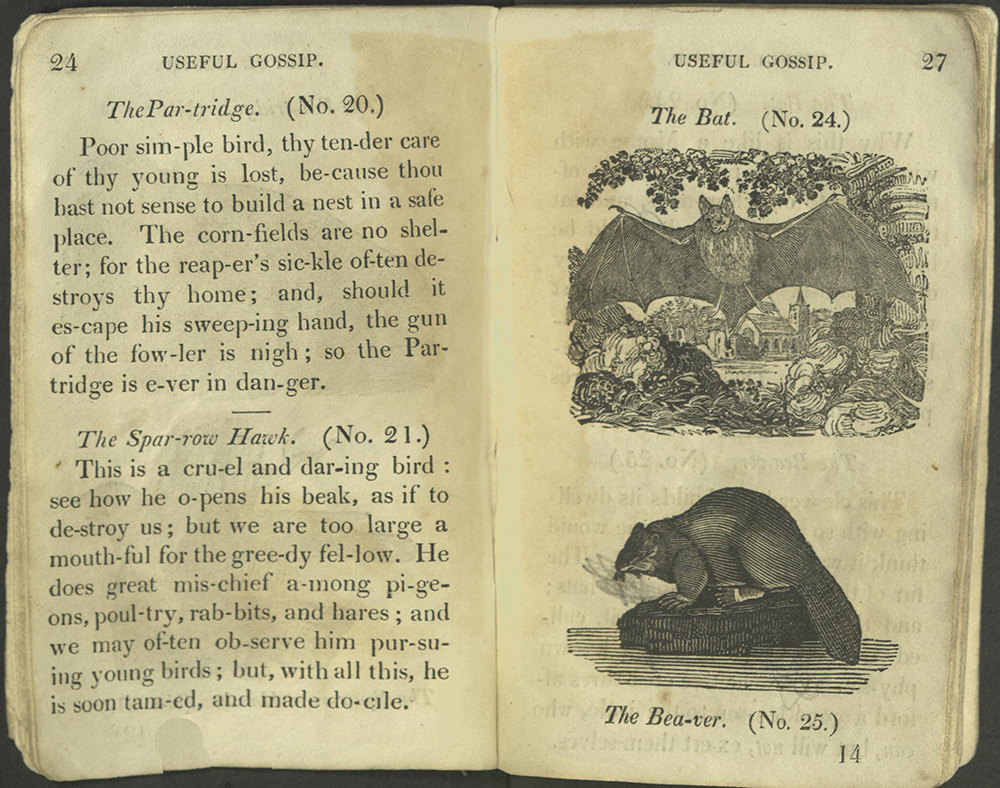

The varying widths of parallel lines to create different tones is used effectively in the image of the beaver

Woodcuts differ from wood engravings in the direction the grain of the wood runs in the block. For woodcuts, the grain runs the length of the block. Wood engravings, in contrast, are made up of closely fitted cross sections of wood, with the grain running the short way, top to bottom. When a wood engraver cuts a block, they cut into the end grain, using v-shaped burins like those used to engrave metal. The result is that they can make very fine lines, producing detailed illustrations – more detailed than those produced by even very good woodcuts. The other benefit to wood engravings over woodcuts is that they are more rapidly cut. This made them the medium of choice for illustrating newspapers and other periodicals with timely content. Like woodcuts, the blocks are durable, and can be used to make thousands of impressions.

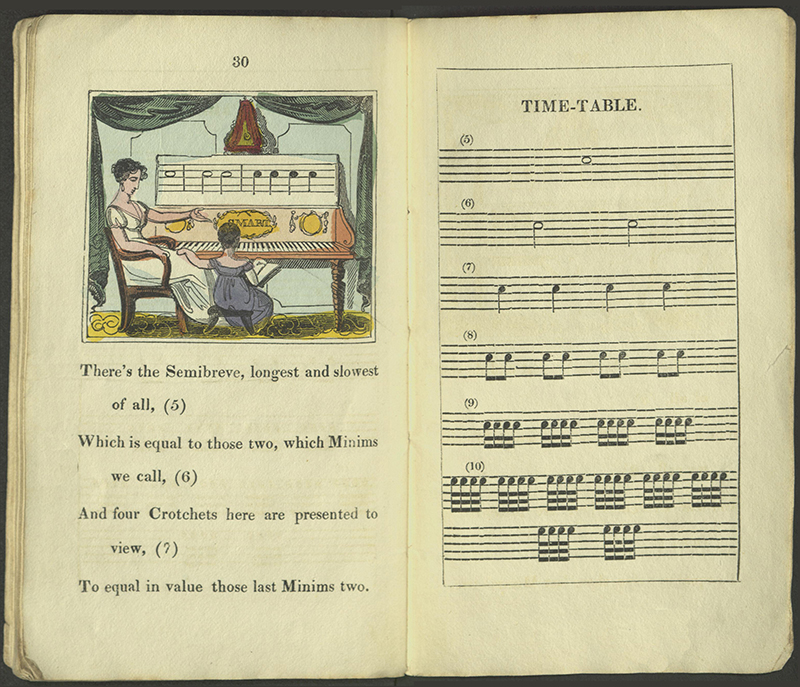

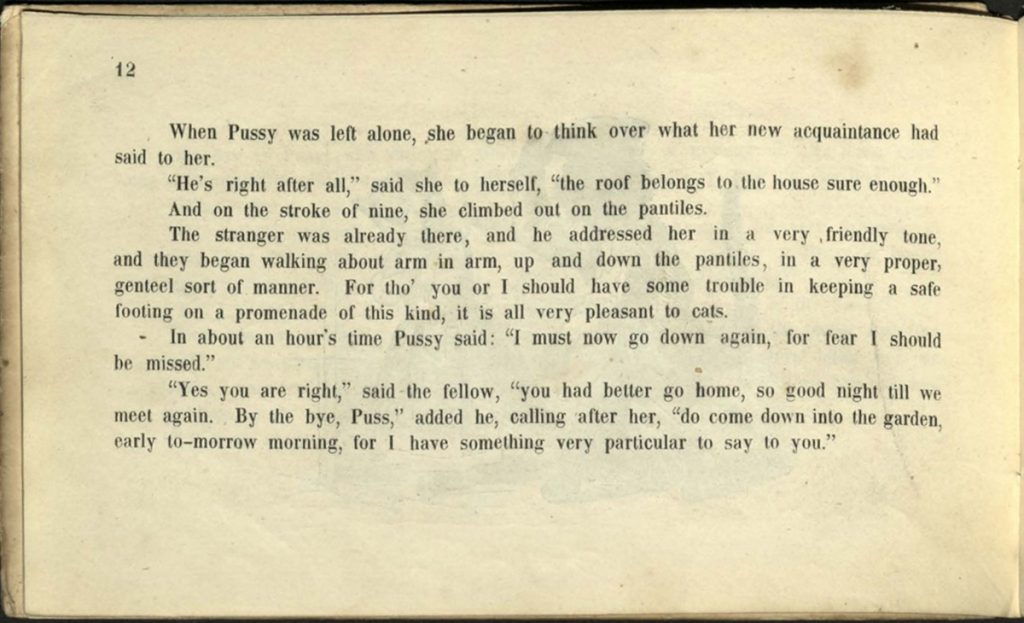

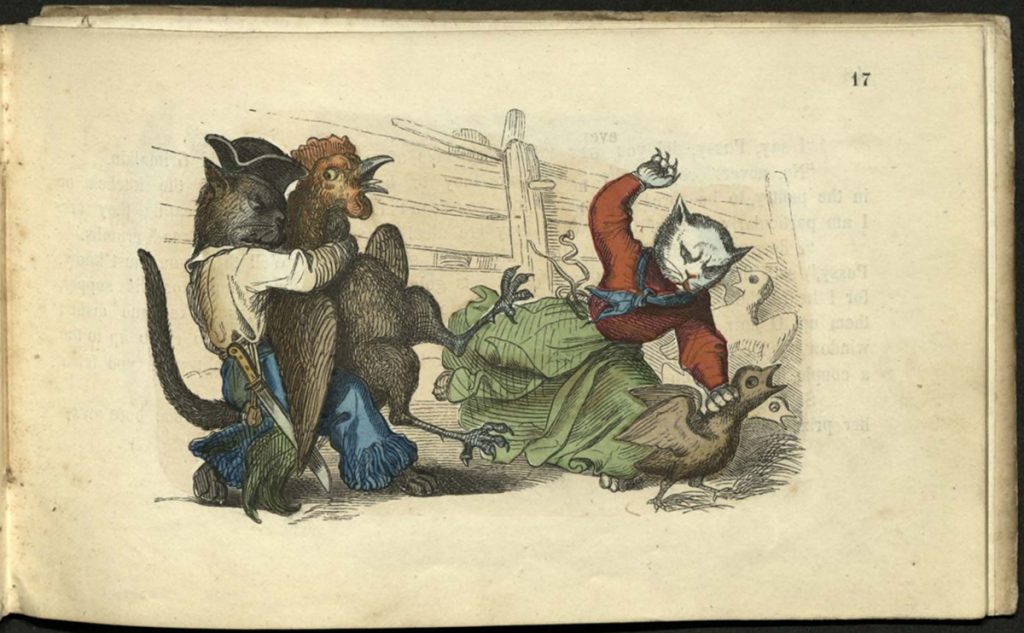

How do you know if you are looking at a wood engraving? If a black and white illustration appears on the same page as words printed from type (same color ink, impression visible on the back of the page, etc.) it is probably a relief print. Between about 1780 and 1840, the chances are good that a print of this sort was made from a wood engraving. (Wood engravings continued to be used into the twentieth century, with other print technologies joining them.) Because a burin removes material, the most important graphic elements are frequently light, rather than dark. The artist “thinks” in white line, rather than in black line. Closely parallel lines, both straight and curving, are characteristic of the technique, and are used to create light and dark areas, depending on the relative widths of the cut away and printed lines.

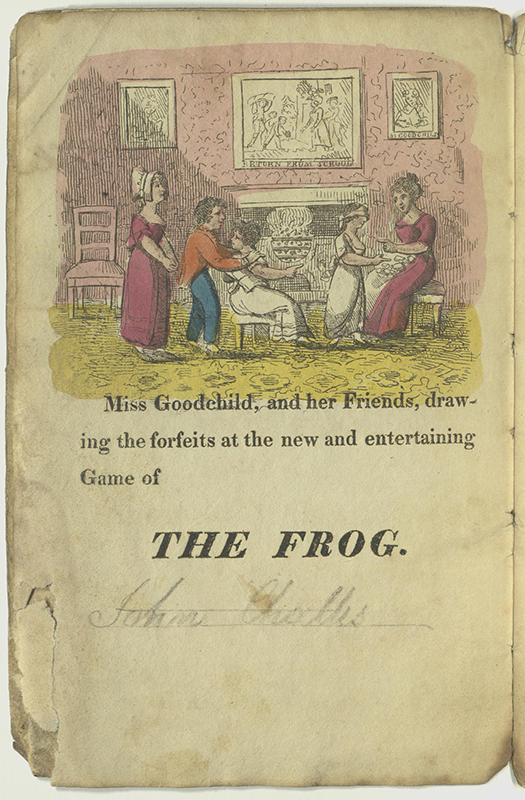

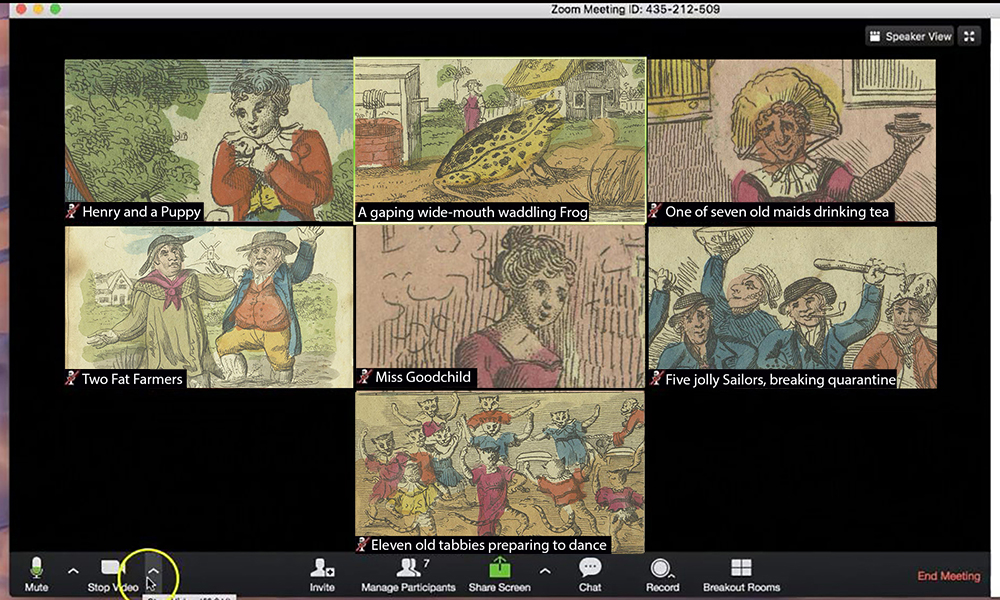

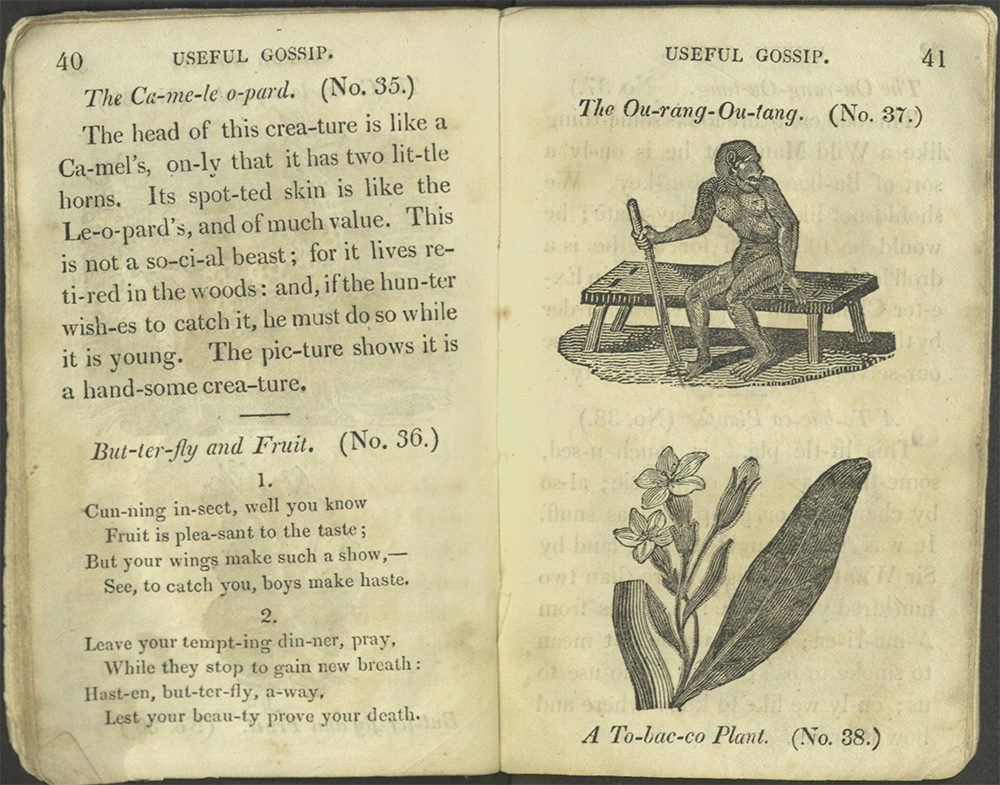

These illustrations come from Useful Gossip for the Young Scholar, or, Tell-Tale Pictures, a strangely various series of short paragraphs of information on birds, animals, plants, and natural phenomena (with additional entries on the auctioneer, plowing, charity, and Englishmen). Bewick is credited as the illustrator by later catalogers – not in the book itself – and many of the pictures are very closely related to works reliably identified as his. Other illustrations were at least based on his images, but they may have been produced by his stable of apprentices or even copied by another wood engraver. The author, Mary Elliott, wrote moral juvenile works to supplement her family’s income and was published by Darton for decades. One gets the general sense that she was asked to produce text to match a collection of likely blocks in the possession of the publisher – an idea we might pursue another day. The text is broken up into single syllables, as an aid to young readers.

In the smaller leaf, the black lines convey shape in the “shadowed” half, and white lines delineate features on the “lighted” side.

Some of the “useful gossip” is factual and some moralistic. The Roller, for example “is of the mag-pie tribe, but we hope he does not chat-ter so much. Many words are not proofs of sense; but we may laugh at a bird’s non-sense, though we ex-pect more wis-dom from cle-ver chil-dren, such as my young read-ers.” And we learn of the tobacco plant that it is employed medicinally, for chewing, and as snuff, but “since we do not mean to smoke to-bac-co, it is of no use to us.” The book is worth reading, at least as a snapshot from 1822 of suitable instruction for the very young.

Marianne Hansen, Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts

Elliott, Mary. Useful Gossip for the Young Scholar, or, Tell-Tale Pictures. London: William Darton, 58, Holborn Hill, 1822

Read our copy on the Internet Archive.

With the continuing closure of the Library, we are blogging regularly about books from the exhibition, The Girl’s Own Book. Please follow us on Facebook or subscribe here for notices of new blog posts.

![Verse 13: Adam and Eve in innocence, God was their glory and defence : Had they continued in that state, Their happiness had been complete. Angels, behold the happy pair, Who did your Maker’s image wear, While in obedience they remain’d And their innocence maintained. Verse 14: In happy Eden see them plac’d, Who stood or fell for all our race; In a sweet bower, composed of love, This happy pair might safely rove. There was no curse upon that ground, Nor changing grief there to be found: There nothing could their joys controul [sic], Nor mar the pleasures of the soul. Verse 15: This land they freely might possess, And live in joy and happiness: Adam was lord of all the land, Made by the great all-forming hand. Eat, said the Lord, of all you see, Except one interdicted tree; And on this truth you may rely, You may not eat that lest you die. Verse 16 (not numbered): Had they obey’d their Maker’s voice, And made eternal bliss their choice, Then everlasting life had been The lot of all the sons of men. But Satan came now in disguise, To blind this happy couple’s eyes: Saying, this fruit now eat, and you Like God, shall good and evil know.](http://specialcollections.blogs.brynmawr.edu/files/2020/06/13through16.jpg)