by Mallory Fitzpatrick, PhD student in Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies

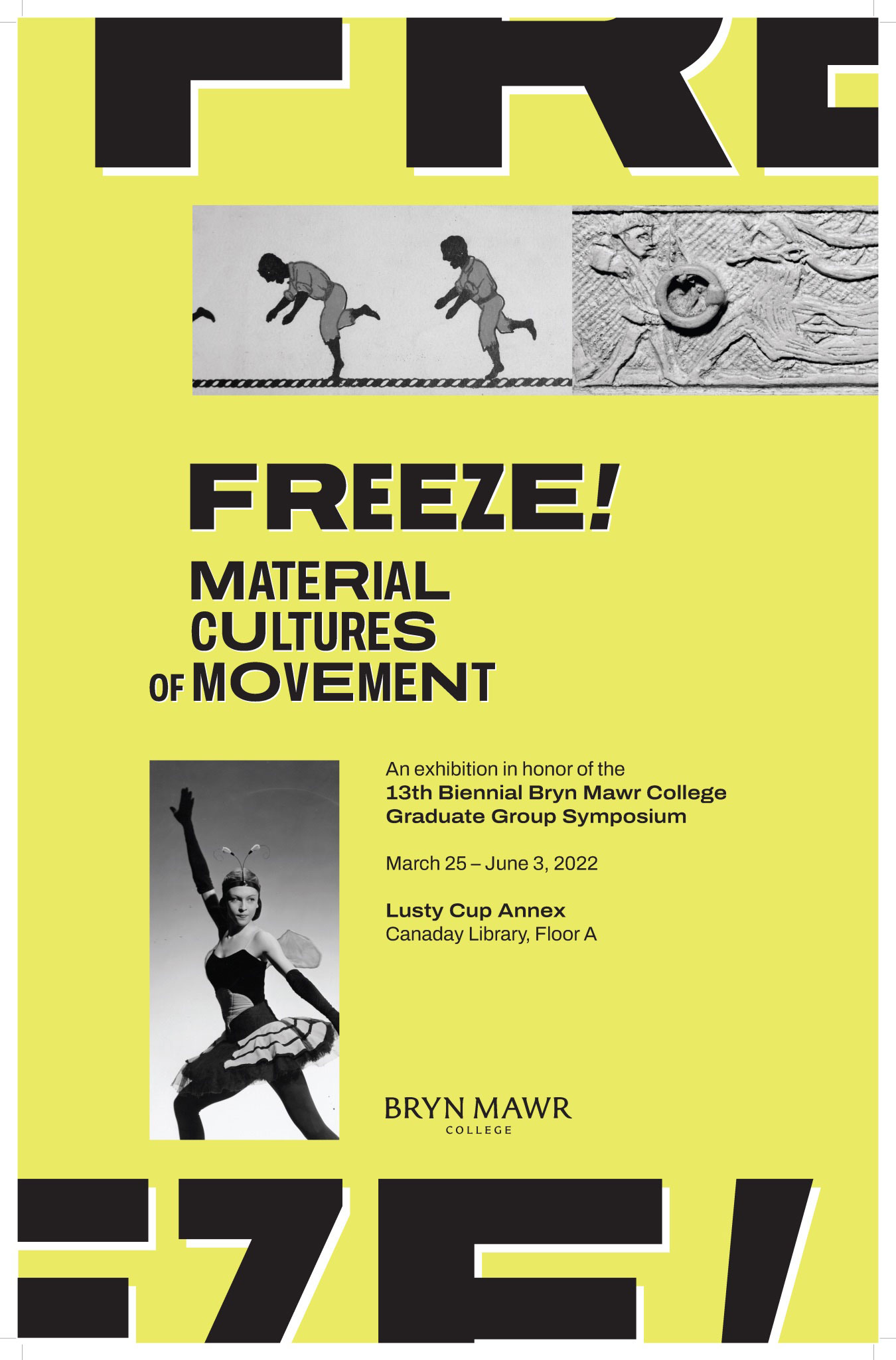

I never knew how many things don’t get included in an exhibition until I started planning one. When my fellow committee members and I began browsing the Tri-Co Special Collections databases for Freeze!: Material Cultures of Movement, the exhibition accompanying Bryn Mawr College’s 13th Biennial Graduate Group Symposium, we worried it would be difficult to find objects that reflected the symposium’s theme, kinesis. But in truth, we ran into exactly the opposite problem—there were far more objects we wanted to include than we possibly could.

One such object was item P.95, a red-figure clay plate from ca. 500 BCE Attica. Perhaps the best-known item in Bryn Mawr’s collection of Greek pottery, this plate, which gives the Bryn Mawr Painter his name, features a bearded man, his arm extended as he tips his kylix—a large, shallow drinking vessel—forward. He’s playing kottabos, a common game at ancient Greek symposia, or drinking parties. The goal of the game is to flick one’s wine dregs at a target in the middle of a room, usually aiming either to knock a small disc from its stand or sometimes to sink small dishes floating in a bowl. (If you’re having trouble picturing this, check out Professor Heather Sharpe’s real-life recreation at West Chester University of Pennsylvania from a few years ago.)

One such object was item P.95, a red-figure clay plate from ca. 500 BCE Attica. Perhaps the best-known item in Bryn Mawr’s collection of Greek pottery, this plate, which gives the Bryn Mawr Painter his name, features a bearded man, his arm extended as he tips his kylix—a large, shallow drinking vessel—forward. He’s playing kottabos, a common game at ancient Greek symposia, or drinking parties. The goal of the game is to flick one’s wine dregs at a target in the middle of a room, usually aiming either to knock a small disc from its stand or sometimes to sink small dishes floating in a bowl. (If you’re having trouble picturing this, check out Professor Heather Sharpe’s real-life recreation at West Chester University of Pennsylvania from a few years ago.)

Bryn Mawr’s kottabos player holds his kylix, ready to take his best shot. The plate didn’t make it into our physical exhibition, but I couldn’t quite let go of the idea of using it for our website. As a classics graduate student, this object with its Greek inscription (ΗΟ ΠΑΙΣ ΚΑΛΟΣ, “the beautiful boy”) found a special place in my heart, as it has for so many Bryn Mawr students and faculty over the years. We couldn’t display the plate itself, due to the constraints of our exhibition space. But, I thought, maybe there was another way to demonstrate its relevance to the symposium.

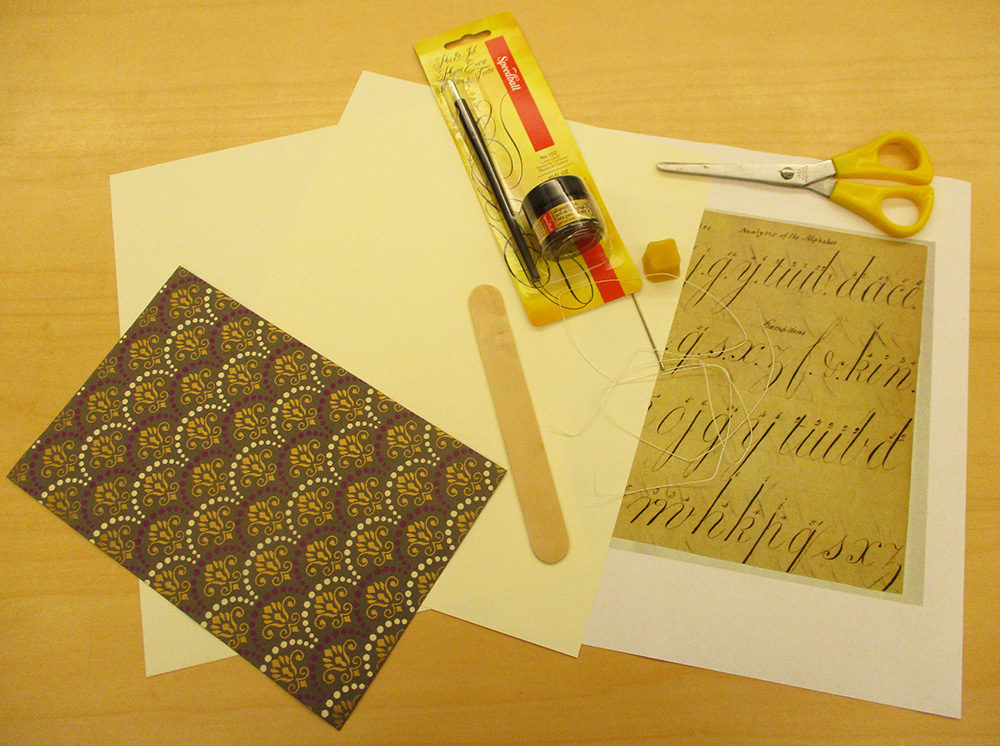

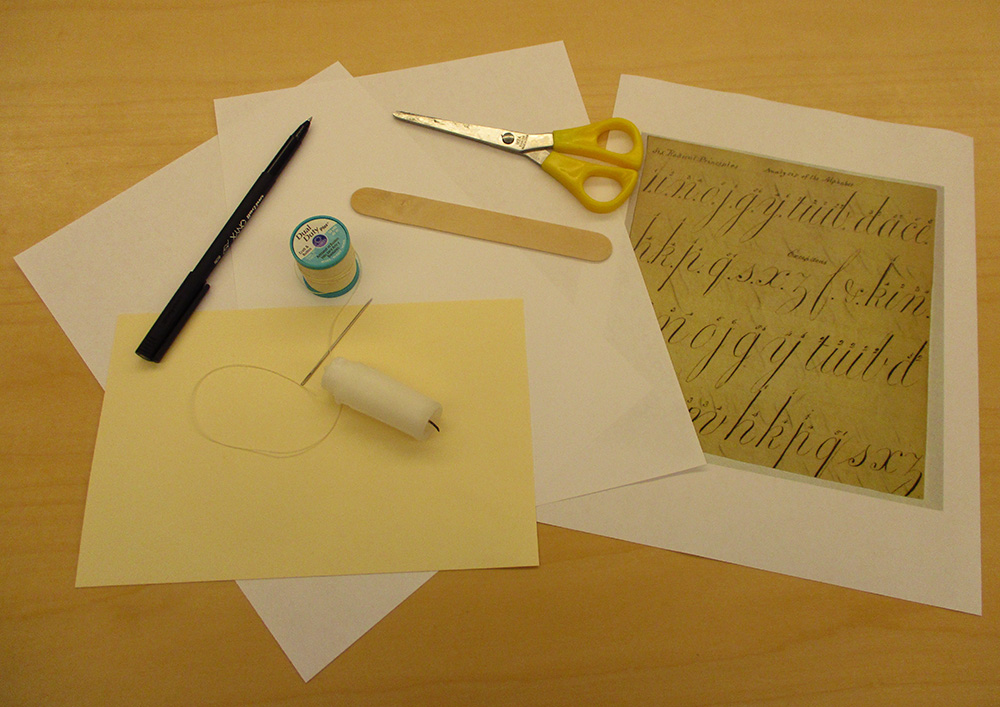

Though the theme of the symposium and initial guiding principle of the exhibition was kinesis, that is, movement and motion, all of our exhibition objects would sit in cases and frames. But using high-resolution images, Photoshop, and a tutorial created by Holly Barbaccia, there was another way to bring static images like the Bryn Mawr painter’s kottabos player to life: to animate the figure by turning it into a GIF.

Most of us are familiar with GIFs, or Graphics Interchange Format, from their ubiquitous presence on the internet. The idea to turn the kottabos player into a GIF came from projects like Image du Monde, which produced animated illustrations from medieval manuscripts. Using the guidelines on their website, I set about animating the kottabos player and other images from the exhibition. It took me a few tries to get the hang of things. In the first version of the kottabos player I made, only his kylix moved. That was neat, but it wasn’t as forceful as I wanted. There was a certain stiffness—why would the cup fly through the air if his arm remained stationary? So I went back to the drawing board and got to work on an improved version.

It took me a few tries to get the hang of things. In the first version of the kottabos player I made, only his kylix moved. That was neat, but it wasn’t as forceful as I wanted. There was a certain stiffness—why would the cup fly through the air if his arm remained stationary? So I went back to the drawing board and got to work on an improved version.

Now the player throws his cup with enthusiasm, his arm completing the necessary movement and hurling the kylix with a much more lifelike motion. This version of the GIF captures the dynamism of the game. But…it isn’t exactly accurate. In a real game of kottabos, the cup wouldn’t leave the player’s hand. (Or at least, it wasn’t supposed to. We may perhaps imagine that sometimes players who’d had a little too much to drink may have accidentally released their drinking vessels, like our overenthusiastic friend pictured above.) The second version of the GIF gives the fullest range of motion to the player, which is what I wanted to highlight for the symposium’s theme of kinesis. But I also wanted to produce a version that was more accurately representative of the game, as seen below.

Now the player throws his cup with enthusiasm, his arm completing the necessary movement and hurling the kylix with a much more lifelike motion. This version of the GIF captures the dynamism of the game. But…it isn’t exactly accurate. In a real game of kottabos, the cup wouldn’t leave the player’s hand. (Or at least, it wasn’t supposed to. We may perhaps imagine that sometimes players who’d had a little too much to drink may have accidentally released their drinking vessels, like our overenthusiastic friend pictured above.) The second version of the GIF gives the fullest range of motion to the player, which is what I wanted to highlight for the symposium’s theme of kinesis. But I also wanted to produce a version that was more accurately representative of the game, as seen below.

Now, our player tips his kylix in a more restrained manner with just enough force to hurl his wine dregs. Success! … At least, partially. According to the Greek comic poet Antiphanes, success in kottabos is all in the wrist, which I neglected to move in this animation.

Now, our player tips his kylix in a more restrained manner with just enough force to hurl his wine dregs. Success! … At least, partially. According to the Greek comic poet Antiphanes, success in kottabos is all in the wrist, which I neglected to move in this animation.

But the kottabos player wasn’t the only image I animated, though it was the most successful. (And is my personal favorite.) As it turns out, Greek red figure pottery is particularly well-suited for this task. The simple color scheme, well-defined lines, and most of all the single, solid shade of the background allows animations like these to look relatively smooth and realistic.

It’s much more difficult to create the animated effects with varied backgrounds and color schemes. For instance, take this photo of an annular eclipse, an exhibition object which is generously being loaned from Haverford College’s collection:

I wanted to animate this photo to watch the stages of the eclipse happen one after the other. But this was much trickier than the kottabos painter. First there was the matter of the grainy pattern and uneven lighting of the photo’s background. I had trouble reproducing the variety of colors and texture.

I wanted to animate this photo to watch the stages of the eclipse happen one after the other. But this was much trickier than the kottabos painter. First there was the matter of the grainy pattern and uneven lighting of the photo’s background. I had trouble reproducing the variety of colors and texture.

After a bit of experimentation, I found a cloning tool in Photoshop that allowed me to replicate the background much better. But there were still challenges. The outlines of the eclipse aren’t as crisp and clear-cut as those of the kottabos player; the lighting of the sun creates fuzzier boundaries, so even when the background has been improved and the speed increased to make a more fluid movement across the sky, this GIF doesn’t quite capture the beautiful glow and luminous detail of the original photo:

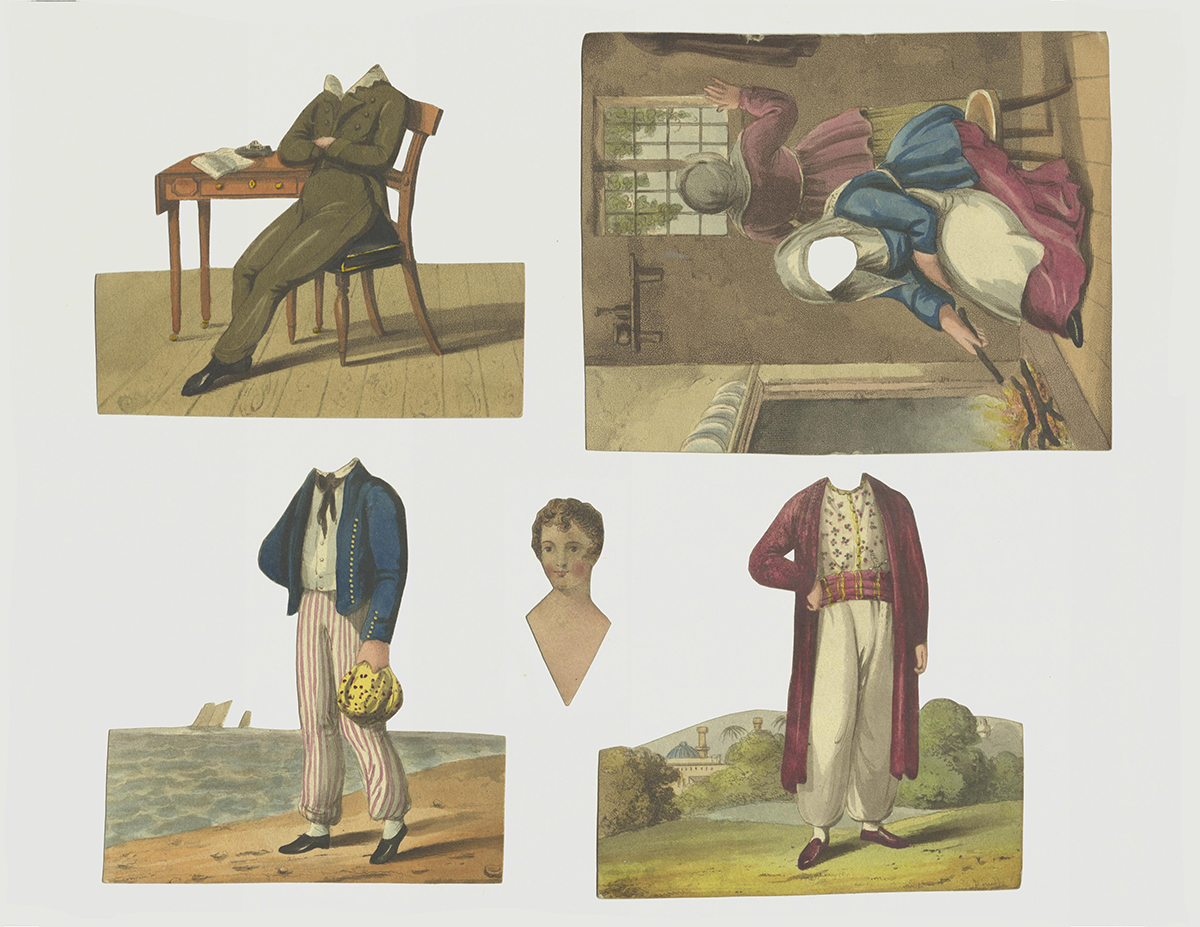

My third and final experiment (for the time being, at least) came from Eadweard Muybridge’s “Animal Locomotion” photograph series. These photographs show sequenced images of people and animals in motion, like plate 617 below, which presents a nude man riding a horse:  Animating this image was a bit different. For the first two, I was only working with one image and moving individual parts of that image to animate it. Here, however, I had twelve images that I was trying to make into one. Instead of manipulating small pieces of a single picture, I separated each of Muybridge’s photos and stitched them together to show our horse and rider in action:

Animating this image was a bit different. For the first two, I was only working with one image and moving individual parts of that image to animate it. Here, however, I had twelve images that I was trying to make into one. Instead of manipulating small pieces of a single picture, I separated each of Muybridge’s photos and stitched them together to show our horse and rider in action:

This one also isn’t as smooth as the kottabos player. Though I didn’t have to match the background the way I did for the eclipse, keeping the dimensions and angle of the Muybridge images aligned turned out to be challenging. With more time and work, I could probably clean it up a bit, but that’s a project for another day.

We’re still exploring the best ways to make use of these GIFs, be it on the exhibition website, the Triarte database, or more informal spaces like this blog. But they provide another way to think about stillness and motion, using images and themes associated with Freeze!, which can be enjoyed on campus in the Lusty Cup annex from March 25-June 3, 2022.

There are thousands of images waiting to be put into motion by amateurs like me—and you! From Greek pottery to medieval illustrations to photographs, what artwork will come to life next?

VISIT THE EXHIBITION!

Canaday Library, Lusty Cup Annex, March 25 – June 3, 2022