This post was authored by Nickie Colosimo, graduate student in archaeology at Bryn Mawr College.

Over the summer, I have been privileged to work in Bryn Mawr’s Special Collections thanks to an NEH internship awarded to me for the study the College’s Roman Terra Sigillata. Terra Sigillata, a slightly inaccurate term meaning ‘stamped clay’, refers to a fine quality ceramic with a red-slipped glossy surface that could be decorated, but also include plain vessels as well. The ware was first produced in Italy and then later in France and the Rhineland, having a very long lived production period which extended from ca. 40 BCE to the early fourth century CE. Currently, the Collections at Bryn Mawr houses over 600 fragments of Roman terra sigillata, many of which were lacking information that could make this collection useful to the College and outside scholars. I spent my internship this summer analyzing the various fragments to determine aspects such as the center of production, vessel shape, date of manufacture, identification of the potter and workshop, method of decoration, etc. Despite their incompleteness, these fragmentary vessels are still able to provide insight into the importance of terra sigillata during the Roman Empire.

The Production of Terra Sigillata

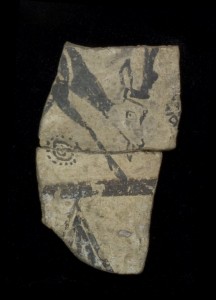

Arretine Terra Sigillata Chalice (Krater, Bowl) Rim Fragment, Late Tiberian - Claudian (30-54 CE), P.1662

Manufacture of terra sigillata was on a massive scale and the vessels were widely exported all over the Roman Empire. The production of Arretine Ware began in the main Italian production center called Arretium (modern Arezzo) ca. 40 BCE where many workshops have been located and which subsequently provided the term widely used to identify terra sigillata made in Italy. Nevertheless, there were other production centers in this region, including Pozzuoli and Pisa, where many of the late Italian terra sigillata vessels were manufactured. The fabric tends to be fairly pale or buff in color and vessels tend to be thin-walled. The slip is more often matte and more orange than red, allowing one to distinguish it more easily from vessels originating in Gaul. Arretine vessels show a desire to mimic metal vessels in their angular and rigid designs. In 1895 Hans Dragendorff published a classification system of the various forms of terra sigillata, which has been expanded by subsequent scholars. A typical form from the major production period of the Arretine Ware is Dragendorff Form 11, a chalice or pedestalled bowl (formerly referred to as a krater), which died out around the middle of the first century CE.

East Gaulish Terra Sigillata Bowl Body Sherd, Late Antonine (180-192 CE), P.2420

Production of the ware shifted to the Roman provinces on the continent during the mid 1st century CE. This ware is commonly referred to as Samian Ware, another misnomer in the study of terra sigillata as it refers to the island of Samos where early scholars mistakenly believed this ware originated. In fact, terra sigillata was manufactured in South, Central, and East Gaul throughout the first through fourth centuries CE. The major periods of production rotated through these areas, beginning in South Gaul, then moving onto Central and finally to East Gaul.

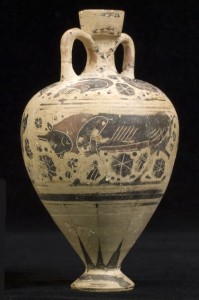

South Gaulish Terra Sigillata Bowl Body Sherd, Claudian, ca. 50 CE, P.2428

The South Gaulish production sites of La Graufesenque, Montans, and Banassac largely replaced the Arretine Ware in the Empire during the mid to late first century CE. In the early period, the vessels from this region are much darker than those of the Arretine Ware with a rather dull and brownish-red slip and a bright red-orange fabric. South Gaulish vessels in the Flavian period, however, had a fabric carrying tiny white flecks and a more glossy dark red slip. Like the Arretine Ware early South Gaulish wares were angular and clear cut, requiring the detailed care of production to mimic the metal prototype vessels. Over time vessel shapes in South, Central and East Gaul became rounded, heavier, and coarser, suggesting a desire for forms easier and quicker to produce. The most characteristic form of this period is the carinated bowl, Dragendorff Form 29, which ceased to be produced ca. 85 CE and which was replaced with the very popular and long lived decorated hemispherical bowl, Dragendorff Form 37.

Vitalis of Matres-de-Veyre, Central Gaulish Terra Sigillata Plage Base Fragment, Late Flavian-Hadrianic (ca. 90-130 CE), P.2600

Central Gaulish terra sigillata reached the height of its production during the second century CE, taking over as the dominant production center. Two major sites in the manufacture of terra sigillata include Lezoux and Les Martres de Veyre. The fabric is hard and dense with an orange-pink color covered in a lustrous orange slip which turns duller over the course of time. Dragendorff Form 37, the hemispherical decorated bowl, continued to be a popular form though it was much heavier and thicker than previous versions.

East Gaul took over the exportation of terra sigillata and became quite popular from the early second century CE onwards. There are a great number of production sites in this region which makes it difficult to speak of a specific fabric, slip, and decorative style. The most popular sites include Trier and Rheinzabern. During this period, most of the standard forms tended not to be made quite the same as before. Additionally, the application of relief molds in the production of terra sigillata phased out, but the use of barbotine and incision continued to be implemented widely. The production of terra sigillata eventually came to an end, although a glossy red pottery similar to Samian Ware continued to be produced in the Mediterranean region in the 4th and 5th centuries, though it does not seem to have been on the same scale or as highly organized as before.

Decoration and Potter’s Stamps

Terra sigillata vessel shapes were highly standardized forms such as cups, plates, and bowls used for serving rather than preparing food. Plain ware terra sigillata was produced on pottery wheels much like other wares of the time. Techniques of decorating terra sigillata include four processes: incising, barbotine, appliqué, and relief-molding. Plain vessels sometimes received incision and barbotine decoration, though appliqué figures were slightly rarer. It is the relief-molding, however, that is the most characteristic decoration of Roman terra sigillata. The process of using relief molds to manufacture vessels first requires a series of stamps or punches that were used to impressing decorative motifs into the bowl-shaped molds which could include floral, faunal, figural, and abstract motifs. The molds were fired and later would have soft clay pressed into it to form the actual terra sigillata vessel. These new bowls would be trimmed, receive a foot ring, dipped into a prepared slip, dried, and fired. As mentioned above, terra sigillata was produced in mass quantities. Excavations of kilns at La Graufesenque, a major production site in South Gaul, have produced tallies of single kiln loads reflecting numbers between 25-30,000 vessels at a time. Such endeavors demonstrate that the production of this ware demanded both an intense commitment on the side of the potter and workshop, but also those engaging in firing, transporting, selling, and buying.

Another aspect of terra sigillata that reveals the sophistication of this ware and it’s manufacture is the potter’s stamp. In many instances, potters impressed their name stamp upon the floor of the vessel or among the decoration, often accompanied by letters such as “F”, “FE”, and “FEC” (meaning, “made it”) or “M” and “MA” (referring to “manu” or “by the hand of”). Stamps often included the owner of the workshop, no doubt a free Roman citizen or freedman, but also could include the name of the slave. A base fragment from an Arretine cup in the College’s collection has a slave’s name, Nicephorus, placed over that of his owner L. Calidius Strigo from Arezzo. Combinations such as this one were quite common on terra sigillata and provide insight into the personnel of these various workshops.

The purpose of these stamps is not entirely clear. Scholars have suggested various reasons including the desire to quantity the output of individual potters in a workshop, to suggest a higher quality lacking in other unstamped and therefore unidentifiable products, and even to identify items made for a specific contract. Whatever their intention, potter’s stamps remain helpful to modern scholars not only in understanding the date of production and representative personnel of these workshops, but also patterns of production and consumption in the ancient Roman empire. This is apparent even in Bryn Mawr’s Collections in which we see the works of potters such as M. Perenius Tigranus, who owned a workshop in Arretium, Italy, appear in Antioch, Turkey. Partnerships between two workshops was possible and exemplified in the Bryn Mawr Collection in the form of a Arretine cup base fragment, the potter’s stamp of which identifies two slaves by the name of Mahes and Zoelus and therefore shows a partnership of two potteries owned by Ateius. Though the nature of this collaboration cannot be certain, it shows an evermore complex picture of the production of terra sigillata.

The Roman Terra Sigillata of Bryn Mawr College

Bryn Mawr’s collection of terra sigillata has diverse origins, including all the major productions centers in Italy and Gaul, as well as a wide distribution pattern from ancient cities like Carthage, Antioch, Ostia, Vidy, and Silchester. A number of fragments were collected in Rome in 1907 and others were donated from the collection of C. Densmore Curtis by Mrs. Lincoln Dryden. A further large part of the collection is due to the scholarship and generosity of the Haverford Classics Professor Howard Comfort, who donated the terra sigillata personally collected over his career. These various donated groups have been partly analyzed by Bryn Mawr graduate Kathleen W. Slane in her 1971 Honor’s Thesis and 1973 Master’s Thesis. My internship this summer has supplemented Slane’s analysis of Bryn Mawr’s terra sigillata, completing the processing of these sherds and providing useful information to make these items meaningful to the College and to Special Collections. For many of the fragments, I have been able to narrow down a production center, vessel shape, date, decorative motifs, and, with the aid of potter’s stamps, potters and their workshops.

As part of his gift to Bryn Mawr College, Comfort included published material from Antioch, Turkey, and Angers, France. This provides Bryn Mawr’s Special Collections with material from two known contexts, an aspect that is rare among the other terra sigillata fragments. Comfort provided the analysis of the terra sigillata that was unearthed throughout the city during excavations in Antioch from 1937-1939 under The Committee for the Excavation of Antioch and its Vicinity. The material from Angers was found beneath the Church of St. Martin during the excavations of G. Forsyth and W. Campbell in 1930-1933. The fragments from both of these sites show that the inhabitants of these cities were importing Roman terra sigilalta made in Italy and France from the Augustan period to at least the Antonine period, revealing that Arretine and Gaulish Ware was distributed widely and for much of the Roman Empire. The fragments of terra sigillata from both of these sites point toward the extensive production and distribution of this ware during the Roman period.

The collection covers all the major production centers of terra sigillata and includes examples of all the major vessel forms representing cups, bowls, and plates. From Italy, Arezzo, Pisa, Pozzuoli, etc. are all well represented and many of those contain potter’s stamps. The prolific workshops of potters like M. Perennius Tigranus and Cn. Ateius are present, but also some of the less well known potters who are known only from their stamps, such as “SES” or C. Se( ). Other vessels come from the continent and production centers in South, Central and East Gaul. There are examples from the most important workshops such as La Graufesenque, Montans and Banassac and a varied group of potters including Calvus, Scotius of La Graufesenque, Cosius, and Primus. The Central Gaulish region is represented nearly entirely by Lezoux, with only a few other vessels of uncertain production sites. Potters from Central Gaul have also been identified and include Doecus, Advocisus, the well known potter Cinnamus, and several others. Eastern Gaul production sites include Trier and Rheinzabern, but due to the large varied nature of the production sites any further identification is uncertain at this time. One potter from this region was identified, Maternianus of Westerndorf.

The Roman terra sigillata of Bryn Mawr College is an expansive collection of material from which both students and scholars of this community and others could benefit greatly. Interested individuals could analyze this material from any angle and find it profitable. Bryn Mawr’s terra sigillata reflects production and distribution patterns, the complexity of pottery workshops and their personnel, the variety of decoration, a healthy collection of vessel forms, and many other topics. This material is a valuable resource regarding the ancient Roman empire and a boon to the Special Collections at Bryn Mawr College.