Shannon Steiner working with a color silkscreen print by Belgian surrealist artist Paul Delvaux. (2012.27.421)

This summer I undertook the pleasant challenge of conducting preliminary research on the donation of works on paper from Jacqueline Koldin Levine ’46 and Howard Levine. As I cracked open the first portfolio and began my research in earnest, I discovered an intriguing pattern of provenance among a number of the prints. The Levine Collection contains quite a few lithographs that were commissioned for sale by The Associated American Artists, a New York gallery and print publishing house founded in 1934. The AAA grew into a large-scale organization that produced large quantities of affordable and attractive works on paper by well-known American artists. The Associated American Artists still exists today in the form of a corporation that manages designer-manufacturer collaboration in the making of household décor and paper goods. I probed the history of the AAA further and learned that the company was essential in creating a market for modern art among the American middle class in the recovery period following the Great Depression. Although print collectors in earlier historical moments had the option of buying individual works and portfolios, the Associated American Artists pushed print collecting into the realm of industry. The AAA organization shaped American taste in art and design on a much larger scale.

This fact brought to my mind a post written earlier this year on a personal indulgence of mine, the popular contemporary design blog Apartment Therapy. The site invited readers (themselves mostly lower- to upper- middle class) to share the maximum amount they had spent on artwork for their home and what the piece meant to them as both consumers and armchair interior designers. The monetary amounts varied wildly, from $0 to $8,000, but the overwhelming consensus within the comments was that original art elevated one’s home above the status of a simple dwelling and transformed it into an exhibition space for the good taste and cultural literacy of its residents. In fact, Apartment Therapy described original artwork as the “raison d’être of successful design,” and readers’ comments revealed that the medium most common to this phenomenon was precisely the same as that marketed by The Associated American Artists – prints and works on paper. A brief look at the history of The AAA can illuminate how art collecting became accessible to the American middle class to such a degree that original artwork at a modest price remains a hot commodity even today. Furthermore, the AAA business model indicates that the gallery consciously marketed the purchase of works on paper as a taste-making endeavor. The AAA prints in the Levine Collection, therefore, offer a unique glimpse into the construction of a middle-class collecting culture.

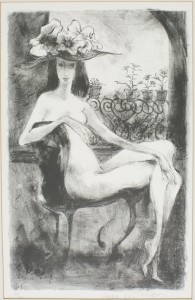

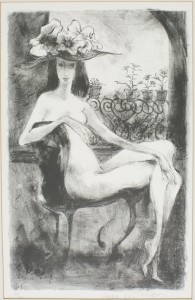

Hilda Castellón, Seated Nude with Flowered Hat, lithograph, after 1964. Commissioned for The Associated American Artists. (2012.27.446)

In 1934, artist agent and publicist Reeves Lewenthal observed that the American art market was restricted to the country’s most wealthy buyers. Original art, primarily painting, was something only the elite could afford to collect. Lewenthal represented a number of art schools with artist faculty producing original works, and thus he kept an eye open for business opportunities that might maximize the resources of his clientele. At the same moment the Federal Art Project, the artistic initiative of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal that ran from 1935-1943, had encouraged artists to make prints en masse for free distribution to public schools and public sector workers. Lewenthal studied the Federal Art Project and its popularity, and he crafted a business model that shared the Federal Art Project’s focus on works on paper, yet aimed for a profit for both himself and his artists.

The Associated American Artists offered prints by reputable teaching artists and by less well-known artists with strong ties to fashionable art movements, in many cases the spouses of famous painters and printmakers. For example, Hilda Castellón, wife of Surrealist artist Federico Castellón, produced a lithograph of a seated nude woman for the AAA in 1964. Her husband’s reputation as a peer of Picasso and Miró made Hilda’s work desirable by association, but Lewenthal’s pricing structure made the work much more affordable. In this case, the Associated American Artists catered to middle-class consumers who possessed an interest in Surrealism but lacked the funds to bankroll the purchase of an original by Dalí or Ernst. Surrealism could thus “go mainstream” and advertise the buyer’s familiarity with and taste for modern art.

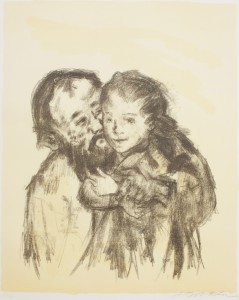

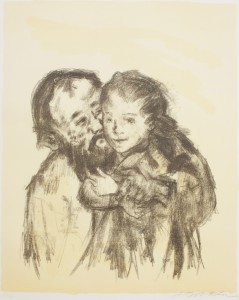

Alexander Dobkin, Paternity, color lithograph, ca. 1950 or later. Commissioned for the Associated American Artists. (2012.27.424)

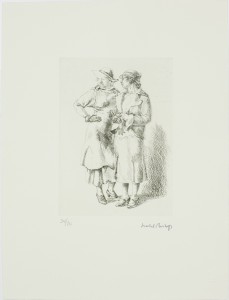

In other cases, Lewenthal took advantage of the institutions he represented as an agent and commissioned prints by respected faculty and chairs of visual arts departments at renowned schools. The Levine Collection contains two lithographs by Alexander Dobkin, an Italian-American artist and art instructor who earned a reputation for his vivacious figure drawings. Dobkin was a popular faculty member in New York City, teaching at both the Art Students League and the Educational Alliance. The AAA commissioned several lithographs from Dobkin in the wake of his success at group exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art and the Art Institute of Chicago, and capitalized on Dobkin’s penchant for warm, family-oriented subject matter. Dobkin was simultaneously modern and familiar, making his prints the perfect product for the AAA’s target customer.

Alexander Dobkin, Confidence, lithograph, 1959. Commissioned for The Associated American Artists. (2012.27.535)

From the end of the Great Depression up until the early 1970s, the Associated American Artists gallery specialized in works on paper. Beginning in the 1960s Lewenthal branched out, and invited artists to design paper and domestic goods, such as stationary, plates, and serving utensils. In this way, the AAA represents the first large-scale artist-as-designer business collaboration. The phenomenon was not unlike today’s designer collaborations with department stores, such as Target’s numerous fashion and home goods lines produced in tandem with high-end design houses such as Missoni and Altuzarra, or clothing store H&M’s diffusion lines from Versace and Karl Lagerfeld. The Associated American Artists could therefore be understood as a pioneer of artistic diffusion, pushing the world of fine art into the living rooms of the American middle class. These living rooms (as well as bedrooms, dining rooms, offices, you name it!) still function as venues for a middle-class interest in art, as the Apartment Therapy post makes clear.

The aim of the Associated American Artists was to make the high-class world of art accessible to middle-class America, and thus the gallery was instrumental in directing the tastes of 20th-century buyers. I look forward to continuing my exploration of the Levine Collection prints and I hope that the AAA prints I’ve found are not my last. These works represent an often-overlooked demographic of the American art market that persists even today as bloggers and their readers carry on the AAA tradition, continuing to equate original printed artwork with good design and civilized gentility.

Shannon Steiner, PhD Candidate, History of Art Department