Hello! My name is Allison, and I am a graduate student in the Winterthur Art Conservation program at the University of Delaware. I received a summer internship placement at Bryn Mawr College to develop my preventive conservation skills. While treatment-focused conservation is concerned with knowing how to stabilize and repair individual objects, preventive conservation is focused on controlling the environment where those objects are stored and displayed through HVAC control, pest management, emergency planning, and storage and housing. With good preventive measures in place, there is a low risk for new damage to occur that may result in the need for specialized treatment. For this reason, a lot of museums and collections are focusing their efforts on preventive conservation, and it is a skill set I wanted to develop.

When I connected with Bryn Mawr Special Collections, the African collection and its storage layout was identified as one in need of evaluation and reorganization. Marianne Weldon, the Collections Manager for Art & Artifacts, and I discussed the following goals:

- To assess the layout of the collection space and reorganize the African collection objects to improve ease of access and safe handling.

- To examine the collection housings and determine where there was a need for adjustments or altogether new housing.

An overall view of Canaday 204 before my reorganization. Many types of objects from multiple collections are housed in this space.

When I began, I could see that all of the collections are overcrowded. But my project was focused on the African collections. These were located across five stationary shelving units, three rolling racks, and two cabinets with pull out shelves. Our main concerns were the proximity of some items to the ceiling, which can be a fire hazard, and the difficult nature of accessing some of the large but fragile objects, such as dance crests and headdresses with suspended elements. The priorities of the reorganization became regaining a ceiling clearance of 18 inches wherever possible and making retrieval and handling safer for the user and the object.

Some objects that are tricky to handle were stored on the highest shelves where they were hard to see and difficult to handle safely.

Work began in a hybrid format. My days on site were spent collecting data. I was given a list of the objects that comprised the African collections and slowly but surely I worked my way through it. I took notes about the objects themselves (materials, geographic origin, name and use) as well as about the housing they were in, be it contained within a box or wrapped in plastic or both. While this data collection was time consuming, by the end I had a good understanding of the materials I was working with and a good intuition for where everything was in the space.

At home I spent time researching methods to approach storage reorganization. Overcrowding is a problem that every collection ultimately faces, regardless of size, so I knew I didn’t necessarily need to reinvent the wheel. Entire reorganization systems have been developed, and there are brief guidelines published by organizations like the National Park Service. As luck would have it, a comparison of the most popular methods was written in 20141 and this was a big help in determining the pros and cons of each approach.

After comparing some options, I had several takeaways.

- Accuracy is important and will save you time and effort

- Much of what has been published is designed with creating new spaces from scratch in mind, rather than making minor adjustments

- There is no one perfect system that can address the needs of every project

By far the most robust system I found is the RE-ORG2 program put together by ICCROM, the International Center for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Heritage. This program is based on a workshop developed by ICCROM and UNESCO to introduce individuals with little prior experience to collection storage management and design. It lays out step by step, with worksheets included, how to assess the current state of a collection, makes plans for a redesign, and execute object moves and relocations. There is a survey that allows a user to examine four areas that impact collection storage (Management, Building and Space, Collection, and Furniture and Small Equipment) and get a score for how their collection ranks in each area.

A screenshot of the RE-ORG program’s “scoring” chart for the African Collections at the onset of this project. Calculated scores are circled.

While I knew I had no control over most of these factors, I found the exercise of filling out the survey a useful way to get a handle on how many ways a collection can be impacted by its surroundings both from a material and managerial standpoint. I was pleased to see that in each category except for “Building and Space,” only minor adjustments were recommended. This solidified my decision to work with my own process, informed by the research I had done, but not prescribing to any one method because none exactly suited my needs.

Each box and item in the collection is a custom size, so I couldn’t make rough estimates based on standards. Because I was dealing with a relatively small space and a manageable number of objects, I decided that I needed to think at an object-specific level to find the best layout.

When I would talk about this project to friends and family, I would often say, “I’m basically playing a big game of 3D Tetris.”

From the measurements of each box and item, I knew I was going to have to change some of the heights on the shelving units to bring the taller objects away from the ceiling. What I needed was a quick and easy way to play with space and see what could fit where without having to move the shelves and objects ten times over. Enter the computer aided design (CAD) app Shapr3D3. Using my iPad, I could literally play 3D Tetris by modeling the whole storage room, shelving units, and objects to scale. From there I could adjust the heights of shelves move objects around and get a plan in place all without having to move a thing in the real world. Starting from zero CAD experience, this intuitive app was a game changer for me, and I can see it having many uses in my future work.

A screenshot from Shapr3D showing Racks 4-7 with adjusted shelf heights and specific objects in proposed locations. This is exactly where these objects ended up!

With a plan mapped out, it was time to enlist some help for the physical move. Margalit Schindler, a classmate in my graduate program, visited for a day to help adjust the heights of shelves and make some of the initial object moves. With a bit of muscle and a lot of clear communication and teamwork, we made the necessary adjustments and brought most of the fragile and hard to reach objects into their new locations. Having a second pair of hands and an outside critical eye was a huge help at this phase of the project. Over the next two days I finished the rest of the object moves, and I am pleased to say that all of my goals were met. Fragile headdresses from up-high traded places with sturdy boxes that were down low, heavy items that were moved to shallower shelves, and the ceiling clearance I wanted was regained nearly everywhere.

A view of Racks 4-7 after the reorganization. The objects that were once high up and on the back of deep shelves are now accessible from the floor with minimal reaching required. Photo: Joy Kruse.

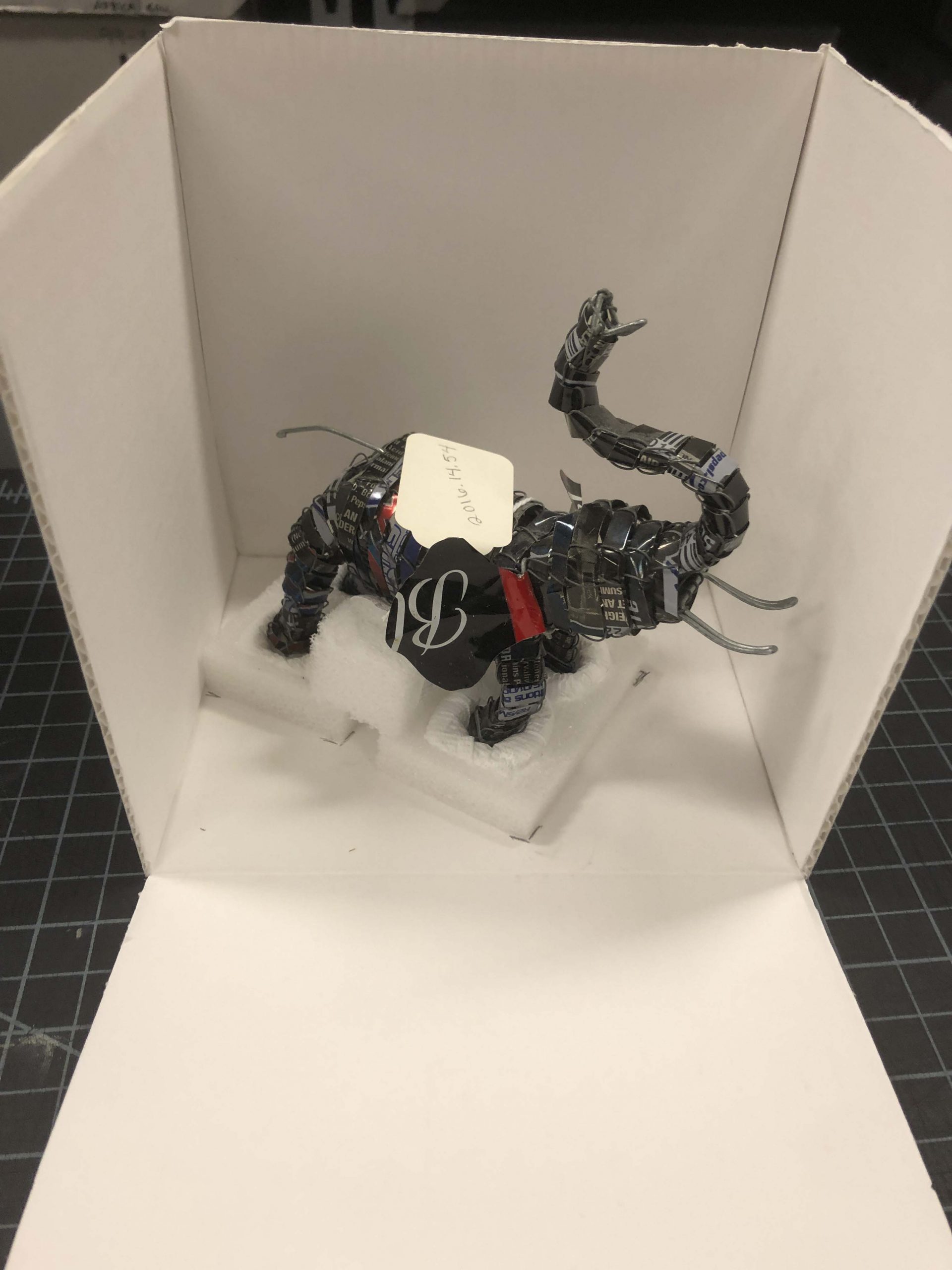

With the big move complete, I was able to focus briefly on housing adjustments. When I was gathering measurements, I took note of the boxes and items I thought could benefit from new padding, wrapping or housing. With the help of Joy Kruse ’23 and Katie Perry ’21, we were able to implement these changes, improving visibility and better immobilizing some of the objects housed in boxes. We also got to discuss what the ideal conditions for objects housed within boxes are in general and the numerous methods and materials one can use to achieve them. It was a good chance for me to practice my teaching the skills and an excellent way for the students to be introduced to different aspects of collection management and preservation. In the end we adjusted more boxes than I had planned, and even built a brand-new box! Many hands truly do make for light work.

Previously wrapped in tissue paper and resting on its side, the new mount on its underside holds the elephant upright, relieving pressure from its delicate ears and preventing it from tipping when the box is handled.

I am so grateful that Marianne and Bryn Mawr trusted me with this project. I gained project management and technical skills, while contributing to the preservation of an excellent collection. I am also pleased that this work can contribute to the overall efforts of Special Collections to confront the legacies of racism and colonialism within their collections. As a conservator, I ask myself two questions when I work on a project: how is my work benefiting the object(s) temporarily in my care and how is my work facilitating interactions with the object(s) be it for research, educational, spiritual purposes or otherwise? Preservation for the sake of making a thing last longer is empty without the motivation of human interaction or engagement with the object driving the work. My hope is that the improved access to the African collections will allow more opportunities for research that can illuminate the complex histories of these objects and aid in any relevant repatriation.

Footnotes

1 Lambert, Simon & Tania Mottus. 2014. “Museum Storage Space Estimations: In Theory and Practice.” ICOM-CC 17th Triennial Conference, 2014 Melbourne.

2 RE-ORG: A methodology for reorganizing museum storage developed by ICCROM and UNESCO https://www.iccrom.org/themes/preventive-conservation/re-org/resources

3 Shapr3D is a computer aided design (CAD) app. During this project, the iOS version of the app was used on an iPad Air 4 with a 2nd generation Apple Pencil. https://www.shapr3d.com/

Allison Kelley is a graduate fellow in the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation. This project was completed in partial fulfilment of her second-year curriculum. All images taken or collected by the author unless otherwise indicated.