This year, many of us are struggling with unfamiliar versions of our celebrations of Hanukkah, Christmas, Kwanzaa, and New Year. Affordable transportation, flexible schedules, and leisure for the middle class (comparable to that available only to the wealthy during Victoria’s reign) have made vacation travel to join family in December an annual pleasure – and obligation – for many of us. As we choose to stay apart this year to protect our loved ones, we may think bitterly of the ideal gatherings depicted in movies and stories, and blame the Victorians for inventing the Christmases we think of as traditional, with a lighted tree, a roast goose (more modernly a turkey), gifts, happy children, and the entire family brought together under one roof.

Of course, we all know that most holiday gatherings fall short of that ideal, no matter how much effort Mother expends. Uncle Harry tells jokes that offend everyone, the turkey takes seven hours to cook instead of five, the children are over-excited and loud, and no one can forget that Grandma died in June. I felt better about the Victorians after finding in the Ellery Yale Wood Collection the 1885 children’s gift book Aunt Louisa’s Holiday Guest, which embodies a far more nuanced depiction of homecomings than one might have predicted.

The publisher’s introduction suggests that the book contains a random assortment of four interesting stories, finishing with one that is topical:

The publisher’s introduction suggests that the book contains a random assortment of four interesting stories, finishing with one that is topical:of Dame Trot.and her Cat is revived with entertaining Pictures; and, in Good Children,

kindness to the afflicted is the subject. Hector the Dog shows his brave adventures on the

mountains; and Home for the Holidays is what all good boys and girls hope for, in order

that they may enjoy in quiet “Aunt Louisa’s Holiday Guest.”

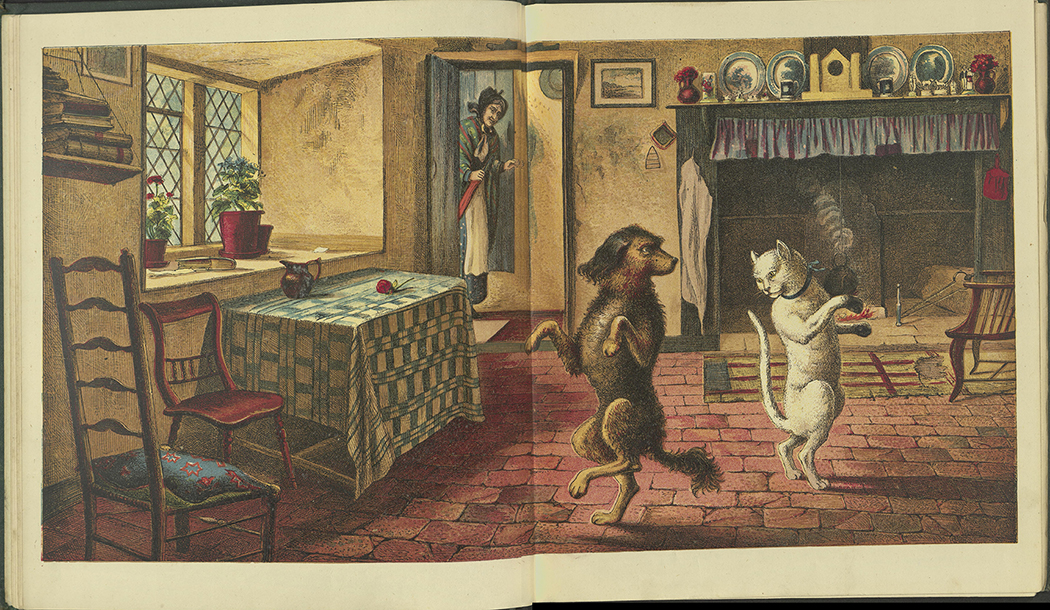

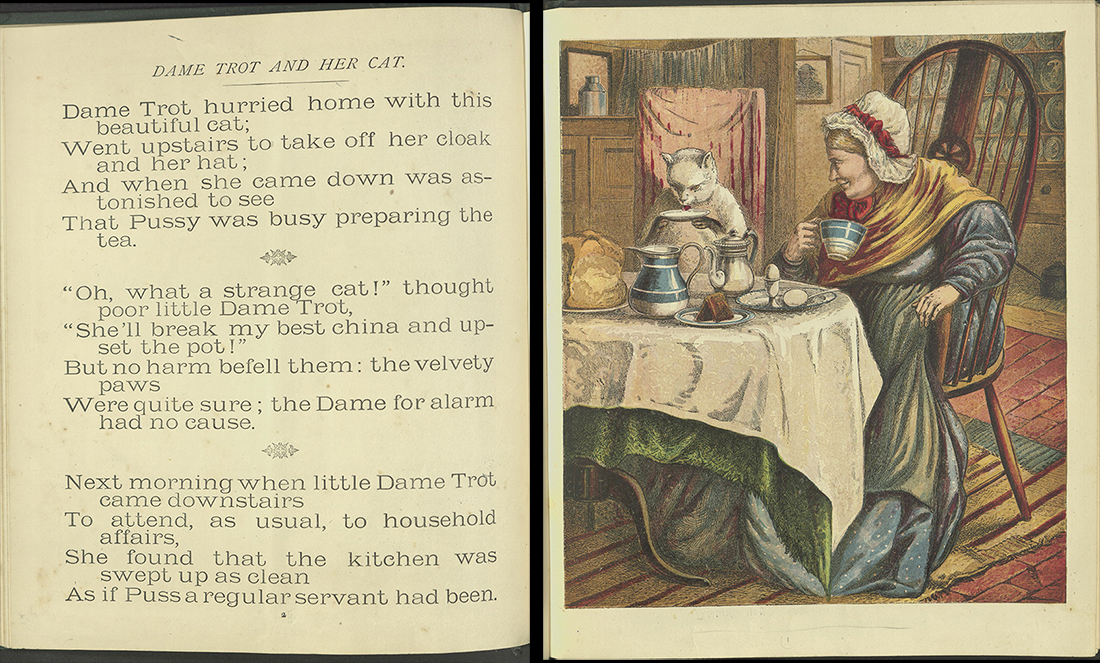

In fact, all four stories are about homecoming and, whether the editor thought about them in this way or not, they illuminate a variety of facets of that uncertain pursuit. Dame Trot and Her Cat was an anonymous work first printed between 1800 and 1805, perhaps as a knockoff of the new popular poem Old Mother Hubbard. The text of Dame Trot is always about the old lady’s cat, but the language and events vary wildly from edition to edition. The narrative, though, has a stable pattern: Dame Trot comes in and discovers the cat doing something unexpected. It has died, or revived, or is making tea, or cleaning the kitchen, or teaching the dog to dance, and so on. Sometimes she has been in the house all along, perhaps coming downstairs after waking up. Frequently she has gone out to shop or pay calls, and she returns home to novel feline behavior.

In fact, all four stories are about homecoming and, whether the editor thought about them in this way or not, they illuminate a variety of facets of that uncertain pursuit. Dame Trot and Her Cat was an anonymous work first printed between 1800 and 1805, perhaps as a knockoff of the new popular poem Old Mother Hubbard. The text of Dame Trot is always about the old lady’s cat, but the language and events vary wildly from edition to edition. The narrative, though, has a stable pattern: Dame Trot comes in and discovers the cat doing something unexpected. It has died, or revived, or is making tea, or cleaning the kitchen, or teaching the dog to dance, and so on. Sometimes she has been in the house all along, perhaps coming downstairs after waking up. Frequently she has gone out to shop or pay calls, and she returns home to novel feline behavior.

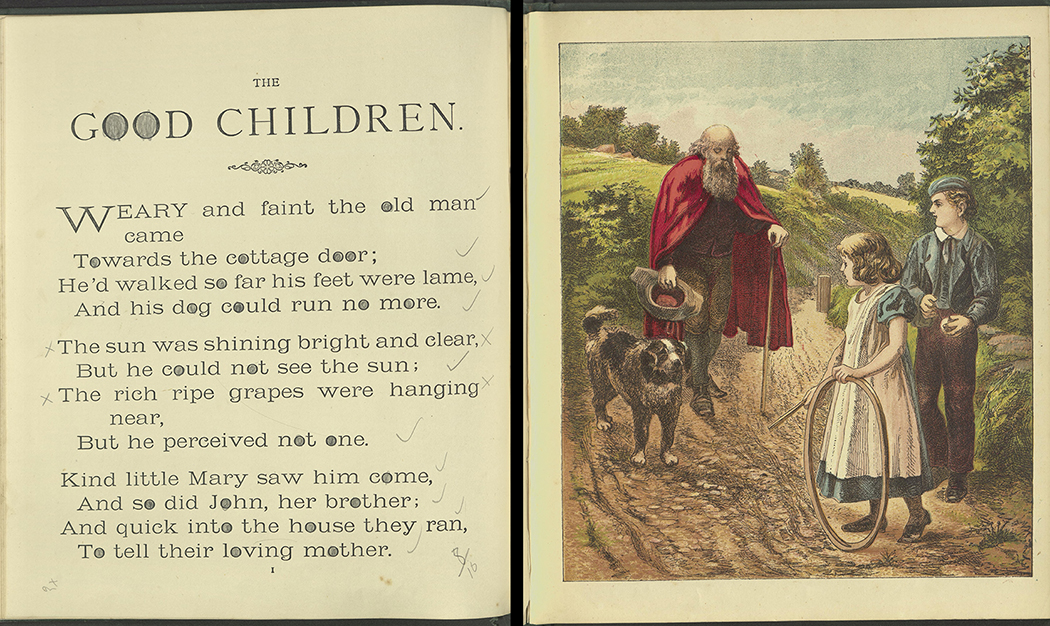

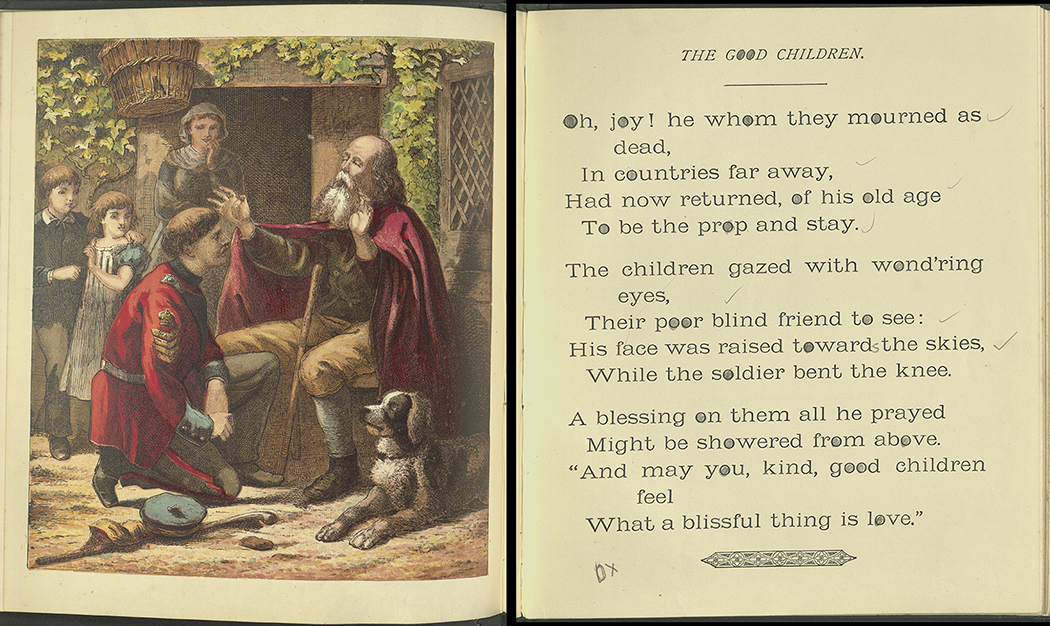

The Good Children is less cheery, focusing on hardships suffered by those who are poor and disabled, especially those whose burden is increased by the absence of family. A tired and hungry blind man, walking with his dog, is welcomed at the cottage where the good children of the title live, and they promptly enlist their mother’s and aunt’s aid to offer him food and drink. The man tells the children about his son, a soldier, whom he has not seen for years because he had been stationed in a foreign country, and who he fears is dead.

The Good Children is less cheery, focusing on hardships suffered by those who are poor and disabled, especially those whose burden is increased by the absence of family. A tired and hungry blind man, walking with his dog, is welcomed at the cottage where the good children of the title live, and they promptly enlist their mother’s and aunt’s aid to offer him food and drink. The man tells the children about his son, a soldier, whom he has not seen for years because he had been stationed in a foreign country, and who he fears is dead.

Miraculously, as he finishes speaking and gets up to leave, his son appears on the road, looking for him. The soldier’s return guarantees the old man’s comfort and support, and sets this small part of the world to right. A homecoming after suffering, and with challenges to come, but an uplifting narrative of family love and filial piety.

Miraculously, as he finishes speaking and gets up to leave, his son appears on the road, looking for him. The soldier’s return guarantees the old man’s comfort and support, and sets this small part of the world to right. A homecoming after suffering, and with challenges to come, but an uplifting narrative of family love and filial piety.

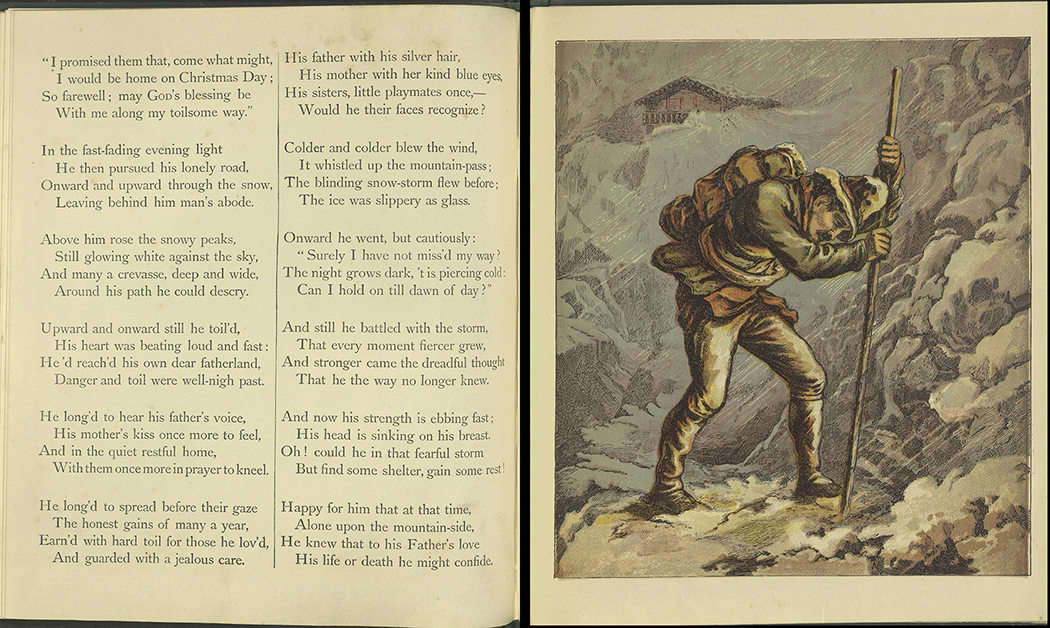

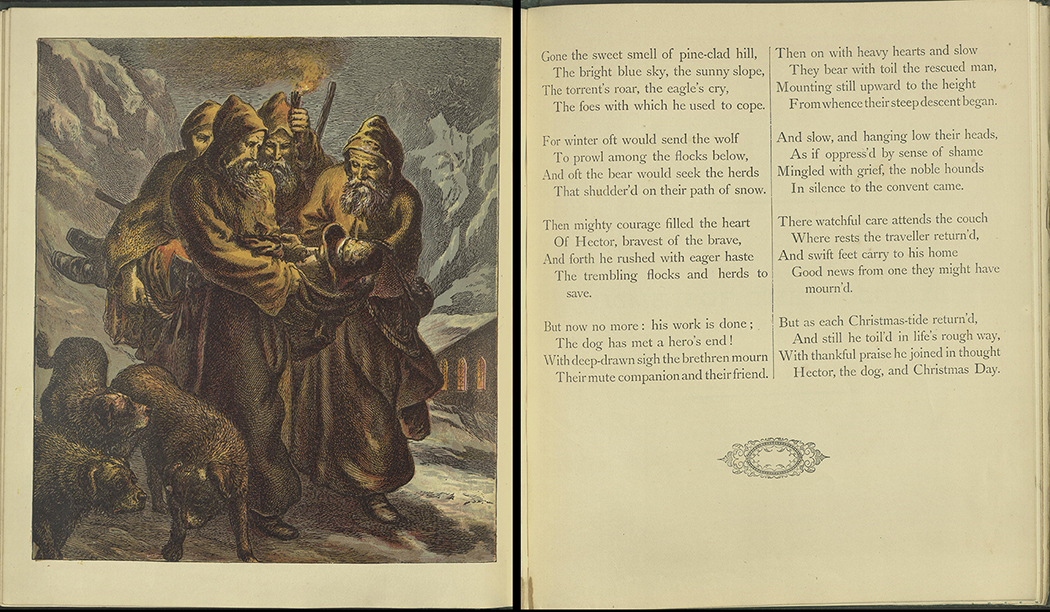

The third story, Hector the Dog, recounts the outcome of an imprudent decision. On Christmas Eve a traveler is in Martigny, Switzerland, intending to go through the Great St. Bernard Pass to get to his family’s home by the next day. An innkeeper, who is familiar with the terrain and the weather predicts a storm and urges him to stay the night. He insists that he knows the pass and that he will go ahead. Of course, the weather is as bad as the innkeeper said it would be, and the traveler is overcome.

The third story, Hector the Dog, recounts the outcome of an imprudent decision. On Christmas Eve a traveler is in Martigny, Switzerland, intending to go through the Great St. Bernard Pass to get to his family’s home by the next day. An innkeeper, who is familiar with the terrain and the weather predicts a storm and urges him to stay the night. He insists that he knows the pass and that he will go ahead. Of course, the weather is as bad as the innkeeper said it would be, and the traveler is overcome.

Fortunately for him, the monks of the Great St. Bernard Hospice make their routine rounds, searching with their dogs for those who need their aid. In recovering the traveler, one of the dogs – the heroic Hector – is buried in an avalanche, but the stubborn traveler survives. The original child readers may have focused sentimentally on the heroism and loss of the dog, but this is also an account of a homecoming gone wrong, where the man’s self-centered and rash insistence on returning on schedule when it was not safe to do so nearly led to his death – and did cost the life of a useful and noble animal who had saved others.

Fortunately for him, the monks of the Great St. Bernard Hospice make their routine rounds, searching with their dogs for those who need their aid. In recovering the traveler, one of the dogs – the heroic Hector – is buried in an avalanche, but the stubborn traveler survives. The original child readers may have focused sentimentally on the heroism and loss of the dog, but this is also an account of a homecoming gone wrong, where the man’s self-centered and rash insistence on returning on schedule when it was not safe to do so nearly led to his death – and did cost the life of a useful and noble animal who had saved others.

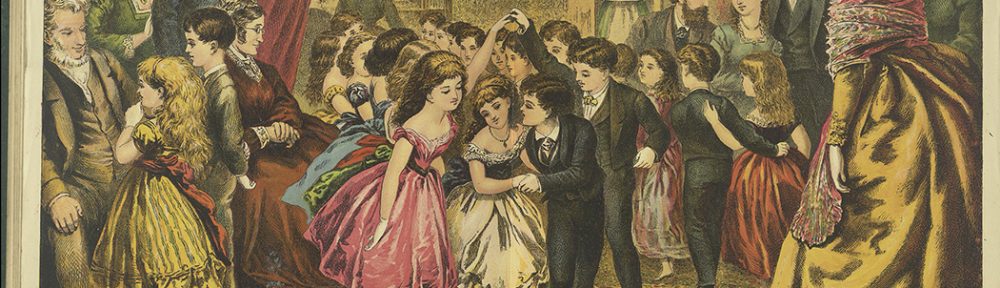

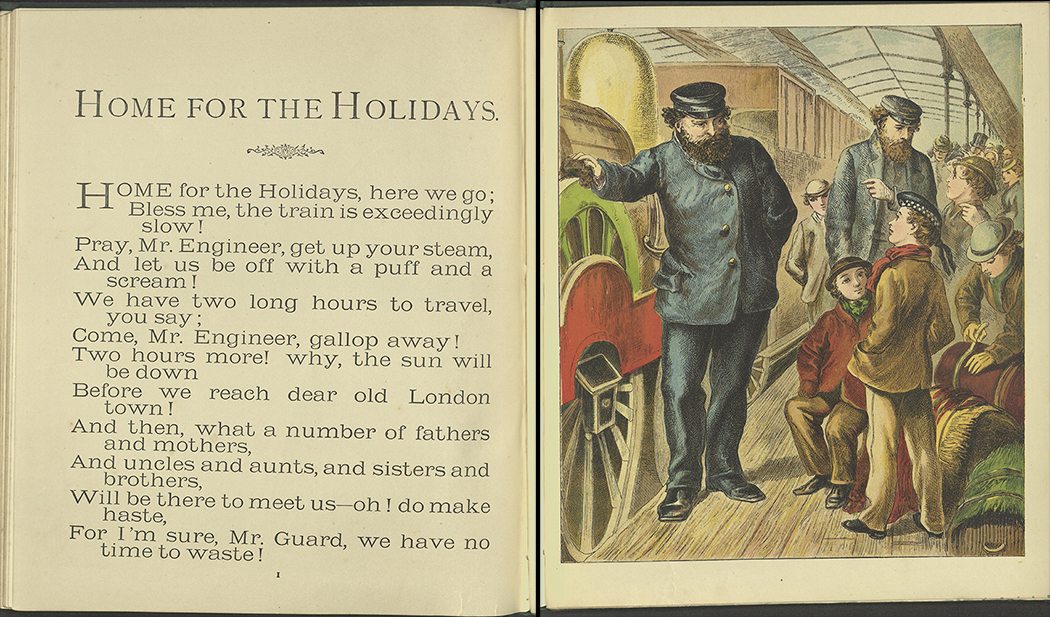

The final story, Home for the Holidays, is a happy version of homecoming, exemplifying the ideal Victorian Christmas that shapes our own expectations. The narrator is a boy, returning to London from boarding school by train with his friends. No archaic nonsense poems or foreign customs here – the poem is entirely up to date with the boy addressing his requests for speed to the guard and the engineer on the train.

The final story, Home for the Holidays, is a happy version of homecoming, exemplifying the ideal Victorian Christmas that shapes our own expectations. The narrator is a boy, returning to London from boarding school by train with his friends. No archaic nonsense poems or foreign customs here – the poem is entirely up to date with the boy addressing his requests for speed to the guard and the engineer on the train.

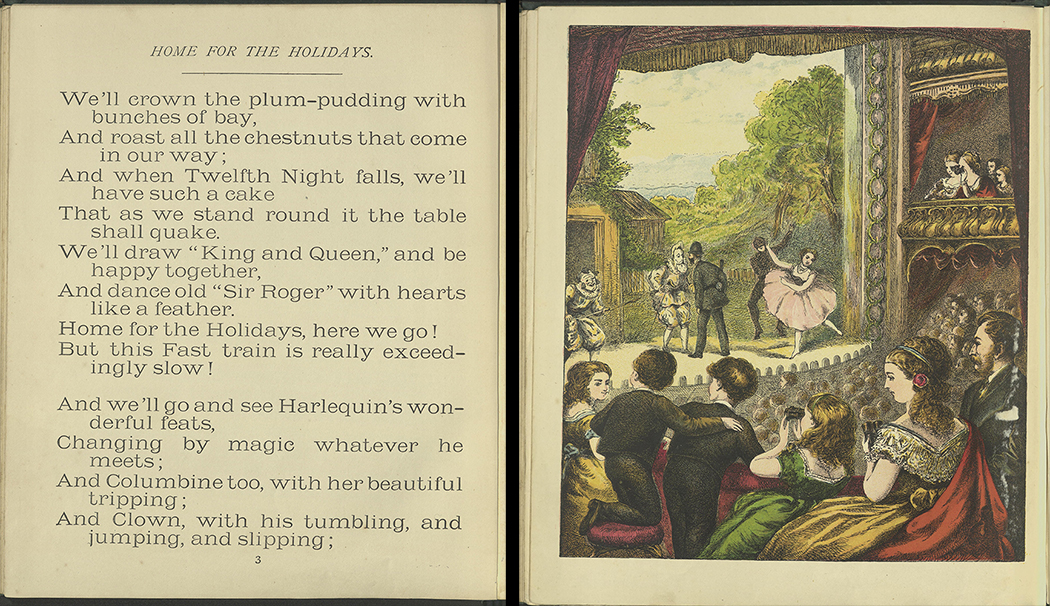

He is as pleased as any student by the prospect of a break from studies, and looks forward to family parties and merrymaking. He mentions Christmas, but he expects the fun to go on through Twelfth Night, and plans to go to the pantomime and an equestrian show, and to see Punch and Judy.

He is as pleased as any student by the prospect of a break from studies, and looks forward to family parties and merrymaking. He mentions Christmas, but he expects the fun to go on through Twelfth Night, and plans to go to the pantomime and an equestrian show, and to see Punch and Judy.

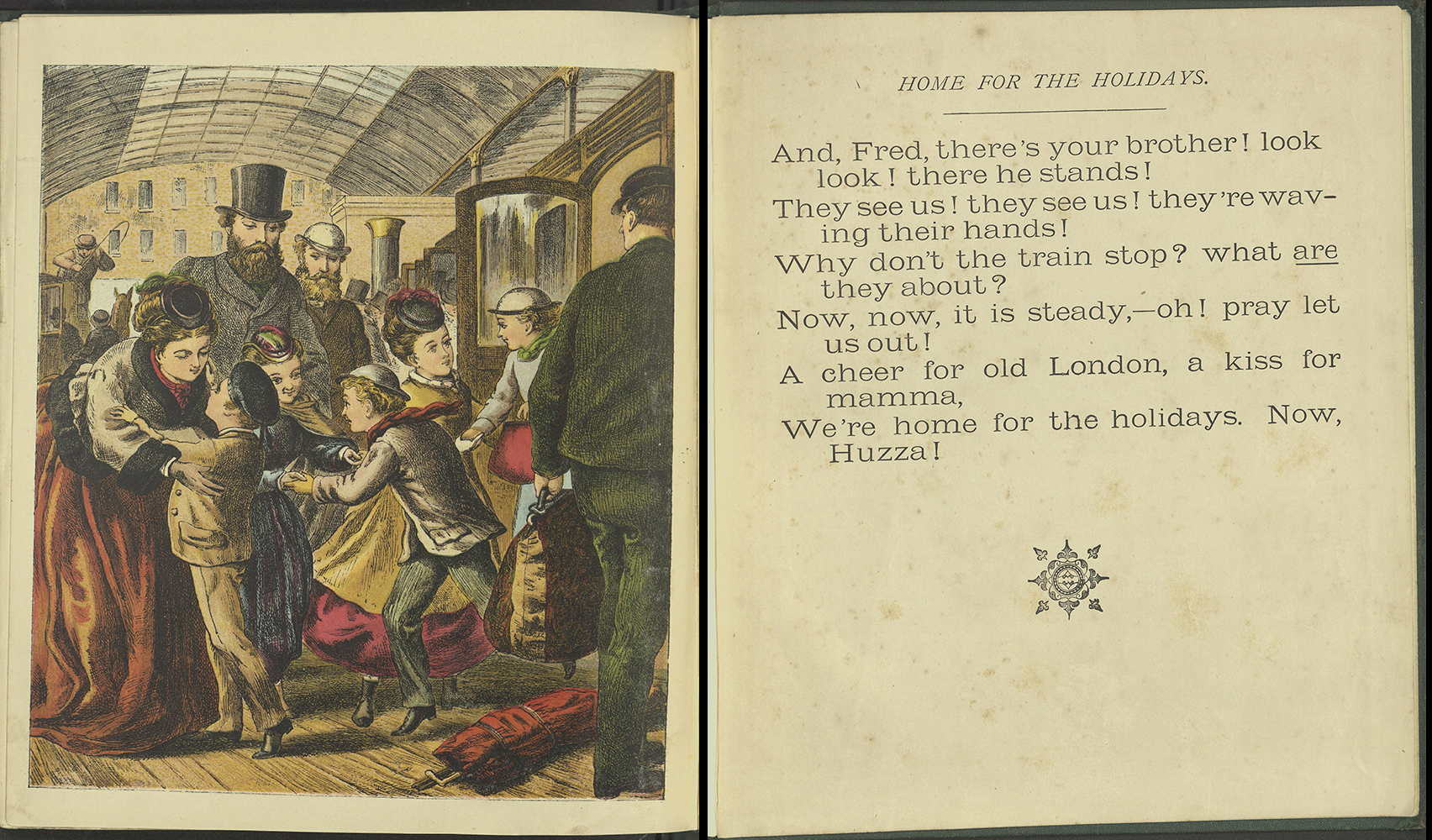

The trip is over at last, and the boys rush out of the train to be embraced by their parents and siblings. Here is the homecoming everyone desires – your friends and family together, good food, your favorite entertainments, and nothing to worry about – and it is this homecoming the publisher ends with.

The trip is over at last, and the boys rush out of the train to be embraced by their parents and siblings. Here is the homecoming everyone desires – your friends and family together, good food, your favorite entertainments, and nothing to worry about – and it is this homecoming the publisher ends with.

I know, as the publisher did, that this is a fantasy, and that for most of us “home for the holidays” is very different. But there is value in optimistic enthusiasm and being willing to be pleased, even this season. I wish you every happiness as you find ways to celebrate the return of light and warmth in the darkness. And we will look forward to a better year to come.

– Marianne Hansen, Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts

Aunt Louisa’s Holiday Guest: Comprising Dame Trot and her Cat, Good Children, Hector the Dog, Home for the Holidays. Laura Valentine., Kronheim & Co., engraver. London: Frederick Warne and Co., c. 1884. Read our copy on the Internet Archive.

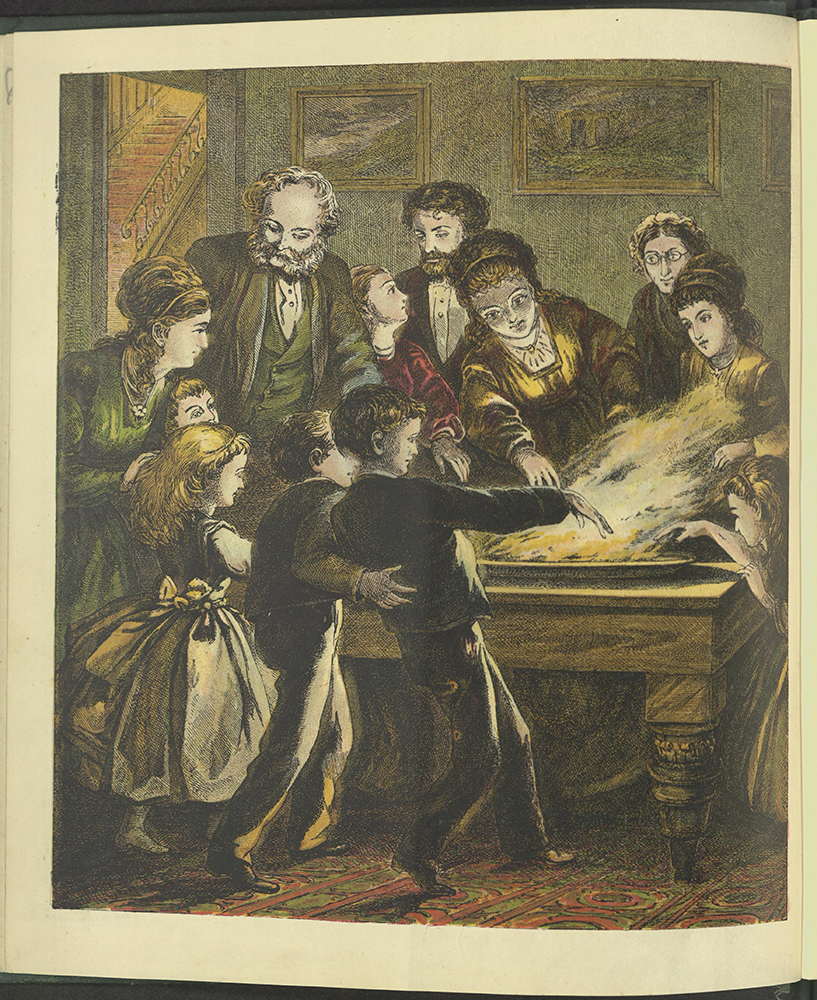

Footnote on Snapdragon

* Snapdragon, the game shown in the first illustration, was defined succinctly in Grose’s Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, 1823: “A Christmas gambol: raisins and almonds being put into a bowl of brandy, and the candles extinguished, the spirit is set on fire, and the company scramble for the raisins.” Read more about it on Wikipedia. Should you choose to play, here are a few useful tips:

Protect your table – nothing flammable; protect finishes from damage by alcohol drips; a hot pad under the platter

Most ordinary ceramic dishes will work. The ideal platter is easy to reach into, with a low, slanting rim.

Warm the brandy gently (~100-110° F) before pouring in the dish, or you may have trouble lighting it. The flames of 40% alcohol are relatively cool. Do not use overproof, which burns hotter.

Enjoy!