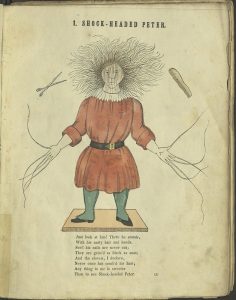

Heinrich Hoffman wrote Lustige Geschichten und drollige Bilder for his three-year old son, creating a persistent pantheon of naughty children to whom hilariously bad things happen. The book was published in 1845 by the Literarische Anstalt J. Rütten – the same year they published Marx and Engel’s first joint work, Die heilige Familie. Although Karl and Friedrich went on to bigger things, Funny Stories and Comical Pictures was much more widely read than the reformers’ first book throughout the century that followed. By 1847 more than 20,000 copies of the German children’s book had been sold, and in that year the same publisher issued a translation, The English Struwwelpeter, or, Pretty Stories and Funny Pictures for Little Children. Struwwelpeter means Shock-headed Peter, in reference to the wild disarray of a shock of harvested wheat, with sheaves piled up to keep the grain off the ground. It is the name of one of the original naughty children in the book, whose striking appearance made him the eponym of the work, even in English, whose native speakers struggle to get their tongues around the word. The German publishers actively defended their copyright in both languages, but the extreme popularity of the work led to an immediate outpouring of new English books which took their inspiration from Hoffman’s poems. Some books had titles with children’s first names (Envious Tom, Naughty Susan, et alia) or the words “Funny” or “Laughter” – or even “Struwwelpeter”. There were also reprints of earlier works which dealt with childish misbehavior, like Sketches of Little Girls and Sketches of Little Boys, originally published in 1838.

The German publishers actively defended their copyright in both languages, but the extreme popularity of the work led to an immediate outpouring of new English books which took their inspiration from Hoffman’s poems. Some books had titles with children’s first names (Envious Tom, Naughty Susan, et alia) or the words “Funny” or “Laughter” – or even “Struwwelpeter”. There were also reprints of earlier works which dealt with childish misbehavior, like Sketches of Little Girls and Sketches of Little Boys, originally published in 1838.

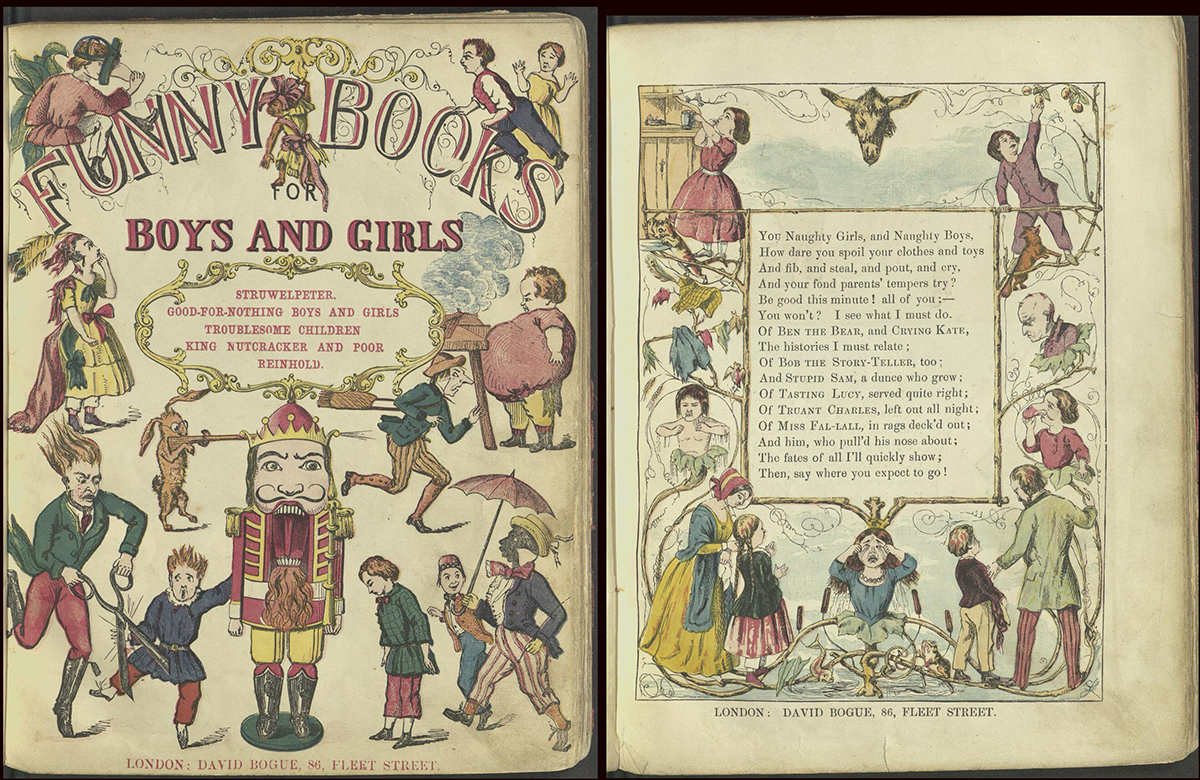

We are gradually expanding our collection of these books about naughty children, but they are relatively uncommon on the market. We do have Funny Books for Boys and Girls: Struwelpeter, Good-for-Nothing Boys and Girls, Troublesome Children, King Nutcracker and Poor Reinhold, published in 1856. In violation of the copyright, it contains a (new translation of) most of the poems in the original, excluding Flying Robert and Shock-headed Peter. It also prints (Heinrich) Hoffman’s Nutcracker, itself part of a complex group of reworkings of E.T.A. Hoffman’s 1816 Nussknacker und Mausekönig. The adaptations of that work include the 1844 version by Dumas, which served as the basis for Tchaikovsky’s ballet.  We also hold the 1857 Little Minxes, the crimes of whose female protagonists include refusing to learn to sew, being a self-obsessed clothes horse, and preferring boyish to girlish pursuits. These redressed Hoffman’s neglect of bad little girls – while reiterating conventional ideas about the sexes and gender roles.

We also hold the 1857 Little Minxes, the crimes of whose female protagonists include refusing to learn to sew, being a self-obsessed clothes horse, and preferring boyish to girlish pursuits. These redressed Hoffman’s neglect of bad little girls – while reiterating conventional ideas about the sexes and gender roles.

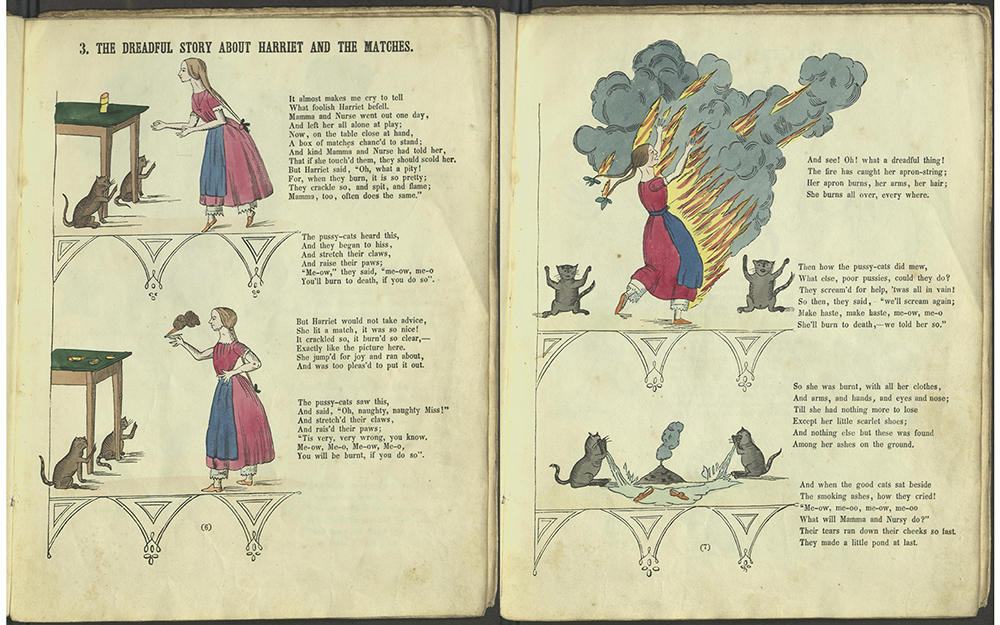

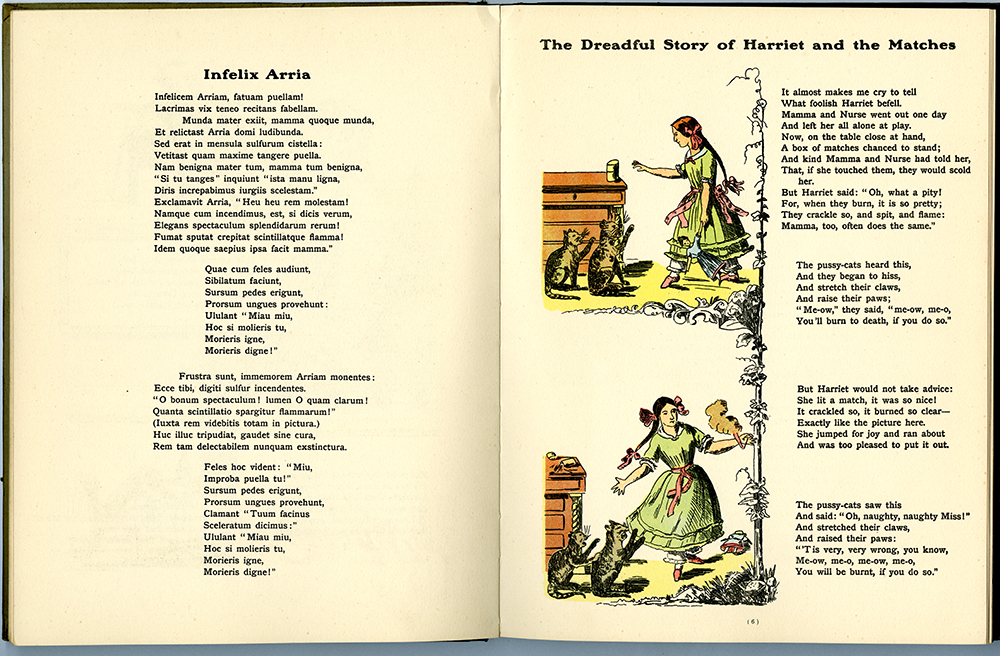

When Rütten & Loening’s copyright expired in 1901, the book was still popular and new translations and illustrations appeared immediately. Here is the original English version (third edition, 1851) of Harriet – Gretchen in the German editions – who played with matches in spite of the instructions of her mother and the last-minute pleading of her cats:

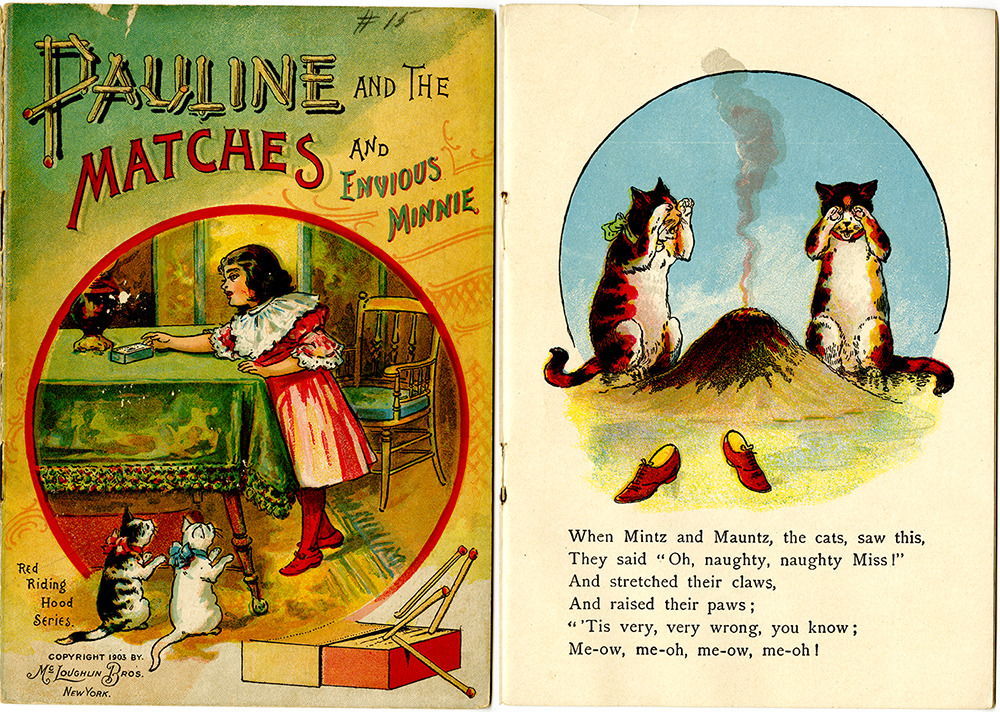

When Pauline, renamed again, was published in 1903 by the American firm McLouglin, she had an up-to-date wardrobe, but the same pyromaniacal impulses.

When Pauline, renamed again, was published in 1903 by the American firm McLouglin, she had an up-to-date wardrobe, but the same pyromaniacal impulses. Translation of the book into Latin took until 1934, when it had entered the public domain.

Translation of the book into Latin took until 1934, when it had entered the public domain. Outright parody had appeared before the copyright expired. Fritz Netolitzky’s Egyptian-themed takeoff was published in 1896, with the faux-scholarly subtitle Being the Struwwelpeter Papyrus: with Full Text and 100 Original Vignettes from the Vienna Papyri.

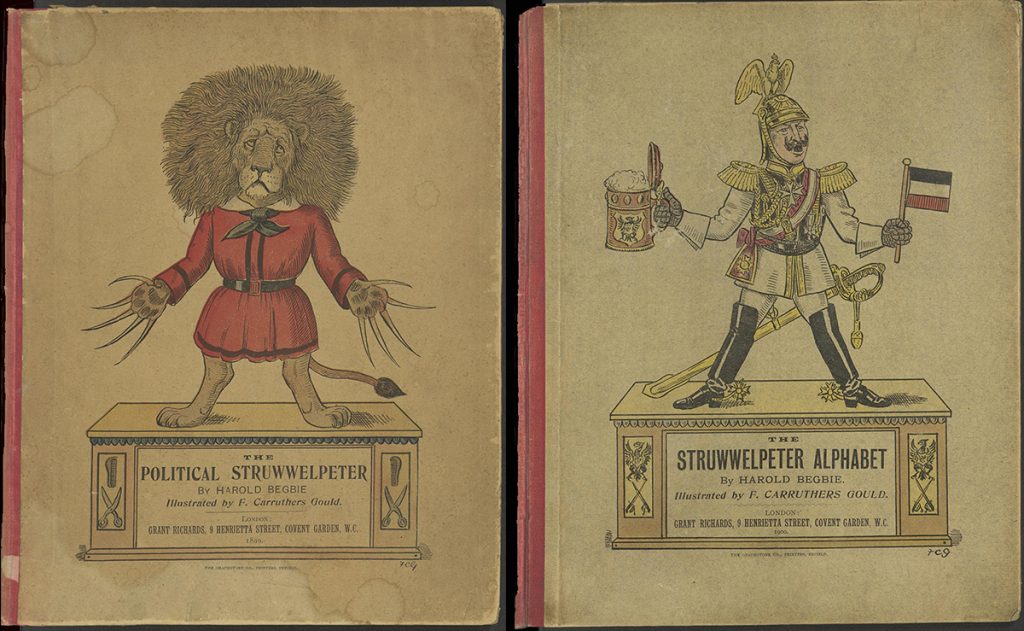

Outright parody had appeared before the copyright expired. Fritz Netolitzky’s Egyptian-themed takeoff was published in 1896, with the faux-scholarly subtitle Being the Struwwelpeter Papyrus: with Full Text and 100 Original Vignettes from the Vienna Papyri. The work found its 20th-century niche as an abundant source of parodic political commentary. Harold Begbie’s books The Political Struwwelpeter and The Struwwelpeter Alphabet use adaptations of Peter’s portrait to make their lineage clear.

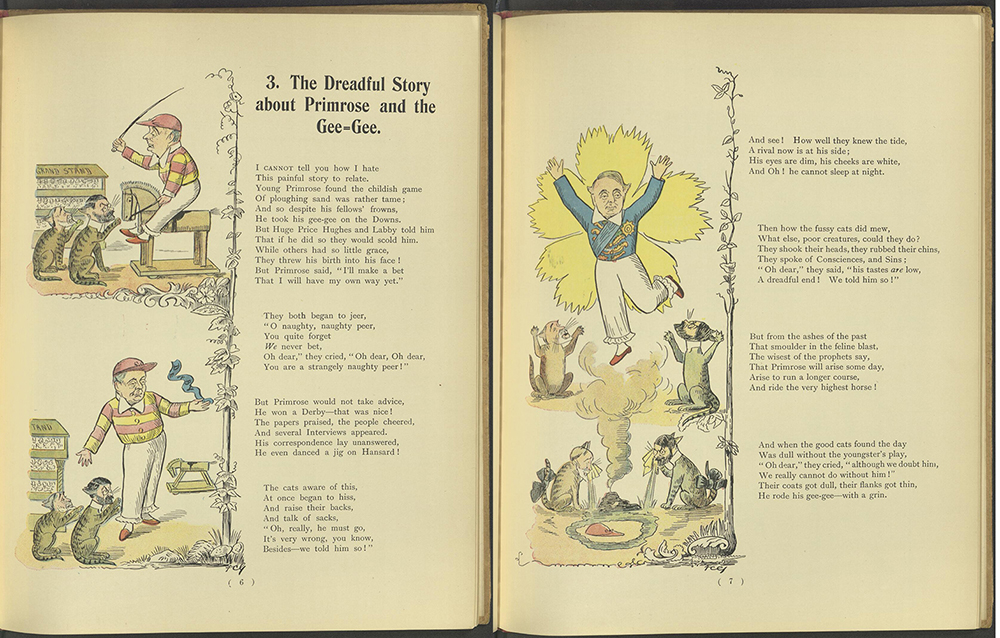

The work found its 20th-century niche as an abundant source of parodic political commentary. Harold Begbie’s books The Political Struwwelpeter and The Struwwelpeter Alphabet use adaptations of Peter’s portrait to make their lineage clear. You can, with effort, decipher both books – unless you are already well versed in late Victorian British politics – but the satire has lost its edge. Harriet’s poem, for example, mocks Archibald Philip Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery, who was Prime Minister from March 1894 to June 1895. He was, as the poem records, interested in racing and two of his horses, Ladas and Sir Visto, won the Derby during his term in office. The critical cat with glasses is the religious reformer Hugh Price Hughes; Wikipedia reveals how unmistakable the identification would be to the contemporary newspaper reader.

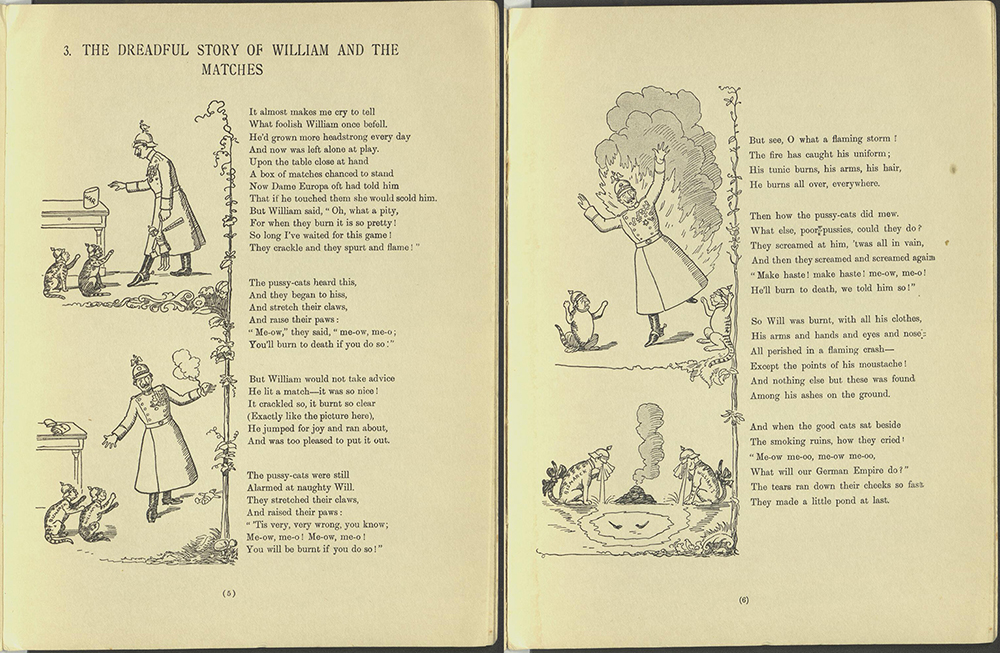

You can, with effort, decipher both books – unless you are already well versed in late Victorian British politics – but the satire has lost its edge. Harriet’s poem, for example, mocks Archibald Philip Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery, who was Prime Minister from March 1894 to June 1895. He was, as the poem records, interested in racing and two of his horses, Ladas and Sir Visto, won the Derby during his term in office. The critical cat with glasses is the religious reformer Hugh Price Hughes; Wikipedia reveals how unmistakable the identification would be to the contemporary newspaper reader. Swollen-Headed William: Painful Stories and Funny Pictures After the German, by humorist Edward Verral Lucas, appeared in 1914. Its criticisms of Kaiser Wilhelm II were far-reaching and harsh. The emperor appears as the protagonist of each of the Struwwelpeter poems – behaving cruelly to those around him, biting (rather than sucking) his thumb as a sign of contempt, and – of course – playing with fire.

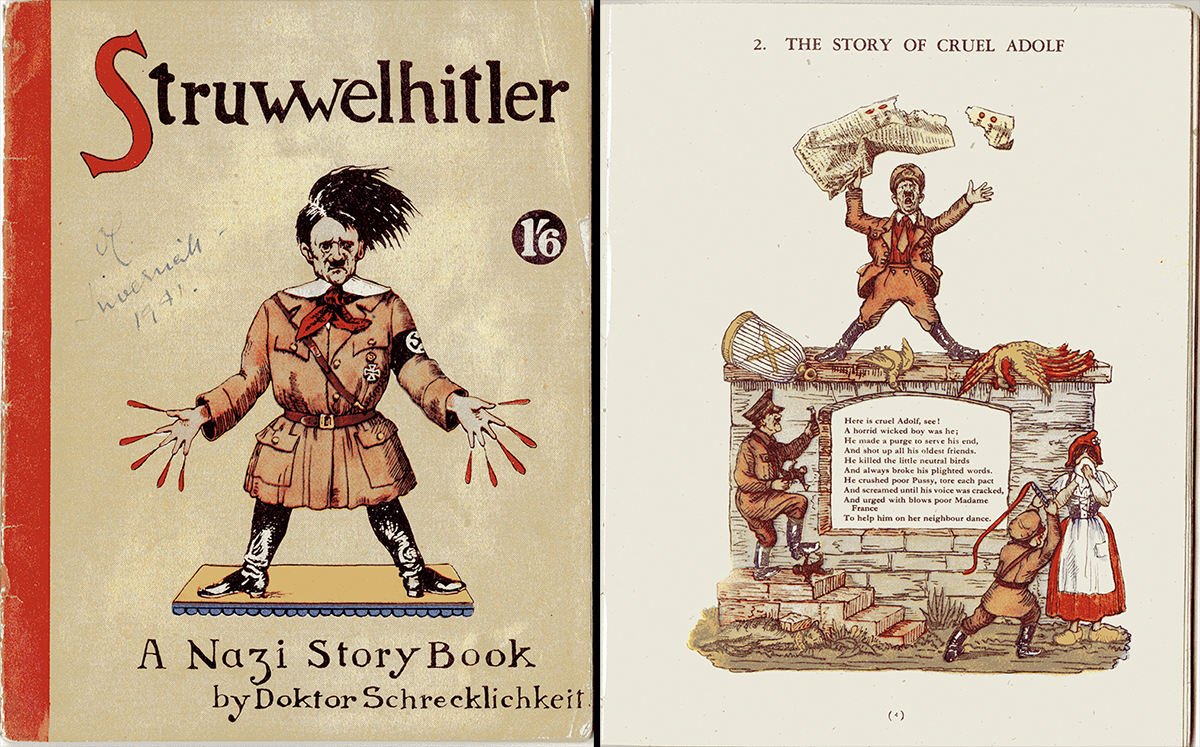

Swollen-Headed William: Painful Stories and Funny Pictures After the German, by humorist Edward Verral Lucas, appeared in 1914. Its criticisms of Kaiser Wilhelm II were far-reaching and harsh. The emperor appears as the protagonist of each of the Struwwelpeter poems – behaving cruelly to those around him, biting (rather than sucking) his thumb as a sign of contempt, and – of course – playing with fire. Political use of the material reached its zenith with Struwwelhitler: A Nazi Story Book, published in 1941 by the British newspaper Daily Sketch. Funds raised by its sale were used to buy radios, games and “woollen comforts” for the troops and supplies for air-raid victims.

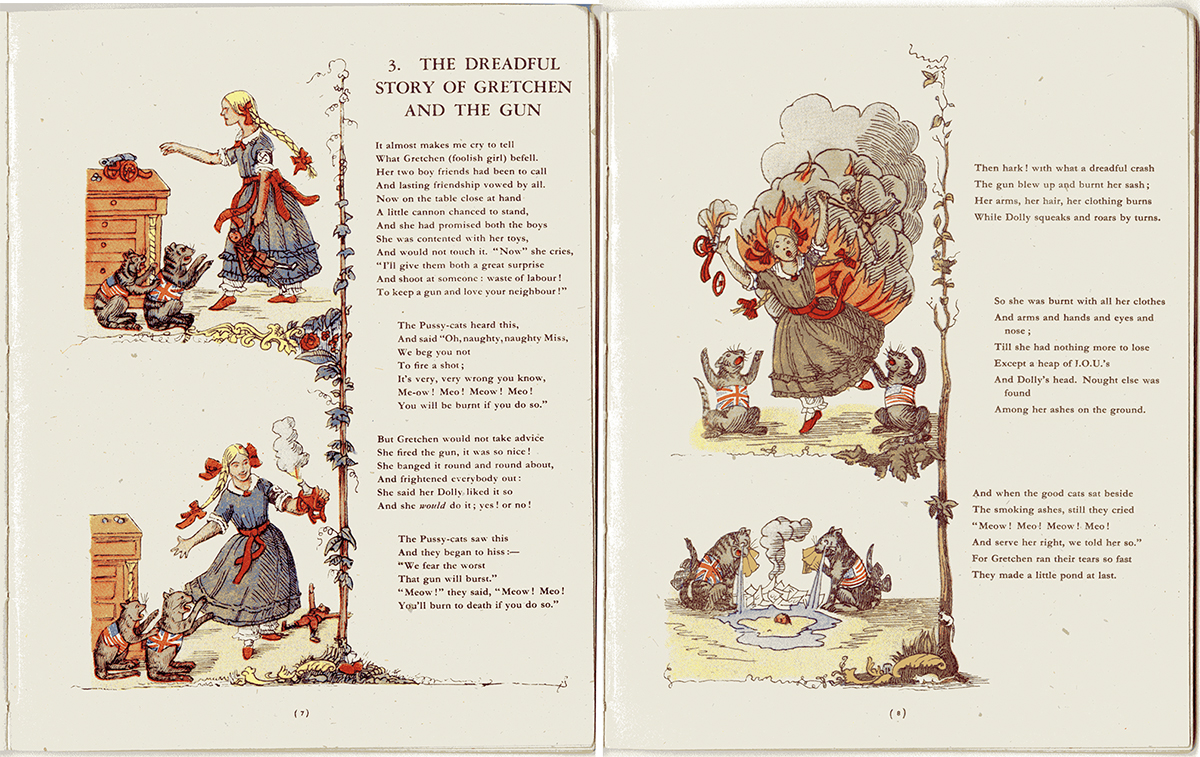

Political use of the material reached its zenith with Struwwelhitler: A Nazi Story Book, published in 1941 by the British newspaper Daily Sketch. Funds raised by its sale were used to buy radios, games and “woollen comforts” for the troops and supplies for air-raid victims.  Hitler takes the place of Cruel Frederick; Goering’s announcement of rationing cuts is mocked in a parody of Augustus Who would Not Have Any Soup; and Little Gobby Poison Pen has his thumbs cut off for writing lies. Switzerland’s armed neutrality was criticized in The Dreadful Story of Gretchen and the Gun. This book’s illustrations are densely packed with visual information, symbolism, and commentary: Gretchen’s dolly falling to the ground, arm still raised in the Hitlergruß, is characteristically poignant.

Hitler takes the place of Cruel Frederick; Goering’s announcement of rationing cuts is mocked in a parody of Augustus Who would Not Have Any Soup; and Little Gobby Poison Pen has his thumbs cut off for writing lies. Switzerland’s armed neutrality was criticized in The Dreadful Story of Gretchen and the Gun. This book’s illustrations are densely packed with visual information, symbolism, and commentary: Gretchen’s dolly falling to the ground, arm still raised in the Hitlergruß, is characteristically poignant.

Times – inevitably – change, but I regret that in the intervening eighty years the book finally fell out of fashion. It is now a curiosity, rather than the rich compendium of shared experience and imagery that made it such a fruitful resource for parody and political commentary. Imagine what a modern cartoonist could do with these tales of cruelty, wilful disobedience, and disregard for human life.

Times – inevitably – change, but I regret that in the intervening eighty years the book finally fell out of fashion. It is now a curiosity, rather than the rich compendium of shared experience and imagery that made it such a fruitful resource for parody and political commentary. Imagine what a modern cartoonist could do with these tales of cruelty, wilful disobedience, and disregard for human life.To read the books mentioned:

The English Struwwelpeter. Our copy is on the Internet Archive.

Funny Books for Boys and Girls. Our copy is on the Internet Archive.

The Little Minxes. Our copy is on the Internet Archive.

Pauline and the Matches and Envious Minnie. Our copy is on the Internet Archive.

The Latin Struwwelpeter is still in copyright and not in the public domain.

The Egyptian Struwwelpeter. Another library’s copy is on the Internet Archive.

The Political Struwwelpeter. Other libraries’ copies are on the Internet Archive.

The Struwwelpeter Alphabet. The Getty Research Institute has added a copy to the Internet Archive.

Swollen-Headed William: Painful Stories and Funny Pictures After the German. Numerous copies are on the Internet Archive.

Struwwelhitler: A Nazi Story Book is still in copyright and not in the public domain.