Away from our collections for three months now, we have been thinking, even more than we usually do, about the importance of immediate, personal, contact with old books, art objects, original manuscripts and records, centuries-old artifacts. Photography and digitization are wonderful tools for research and education. At the same time, the study of material culture, which draws on objects to help make sense of human activity and thought, is deeply enhanced by firsthand experience with those objects. If you can turn the pages of a book, you have access to information about its size, structure, and materials at a level even the best imaging and software do not deliver. Through your own manipulation of the volume, you gain insight into the experiences of the original audience and makers.

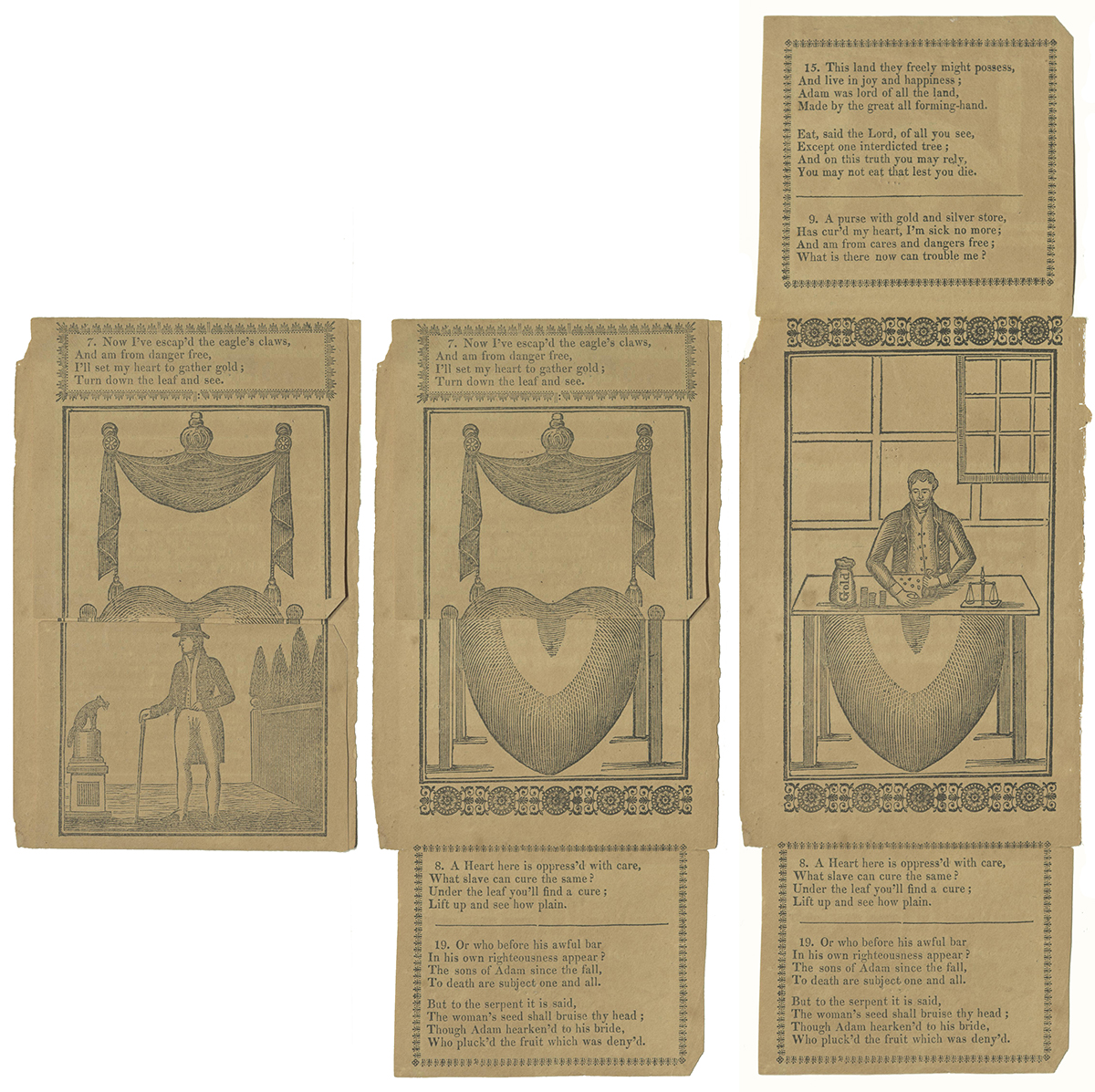

Metamorphosis, or a Transformation of Pictures is an especially difficult object to describe or understand without handling, its physical and intellectual arrangement best revealed by experiment. This is perhaps the key to its historical success – it is foremost a puzzle, and even if the content is familiar to the reader, it is an engaging pastime to follow the instructions and trace the path of the verses.

Even experienced remotely, it is a fascinating example of Americana and of early books aimed at children. Since we cannot look at it together, I will offer up the parts in various combinations. But we must accept that it is a poor substitute for handling the pages and trying out different arrangements of flaps, reading the texts as they appear near one another (out of “order”), and simply playing around.

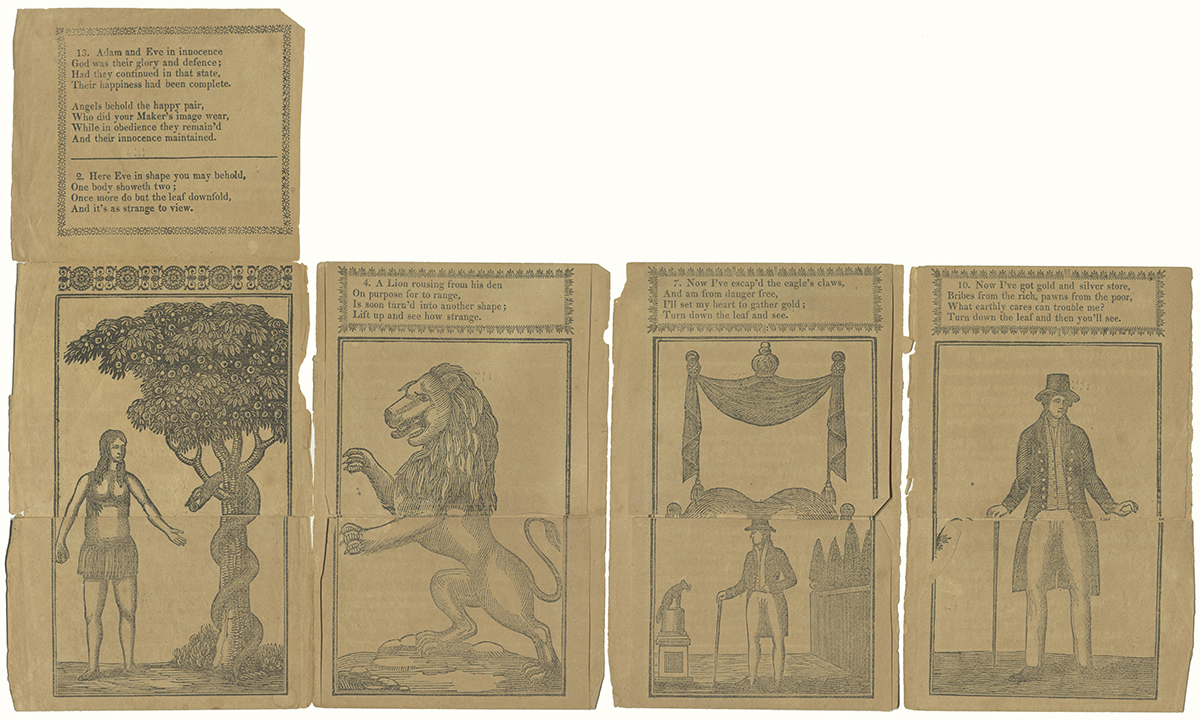

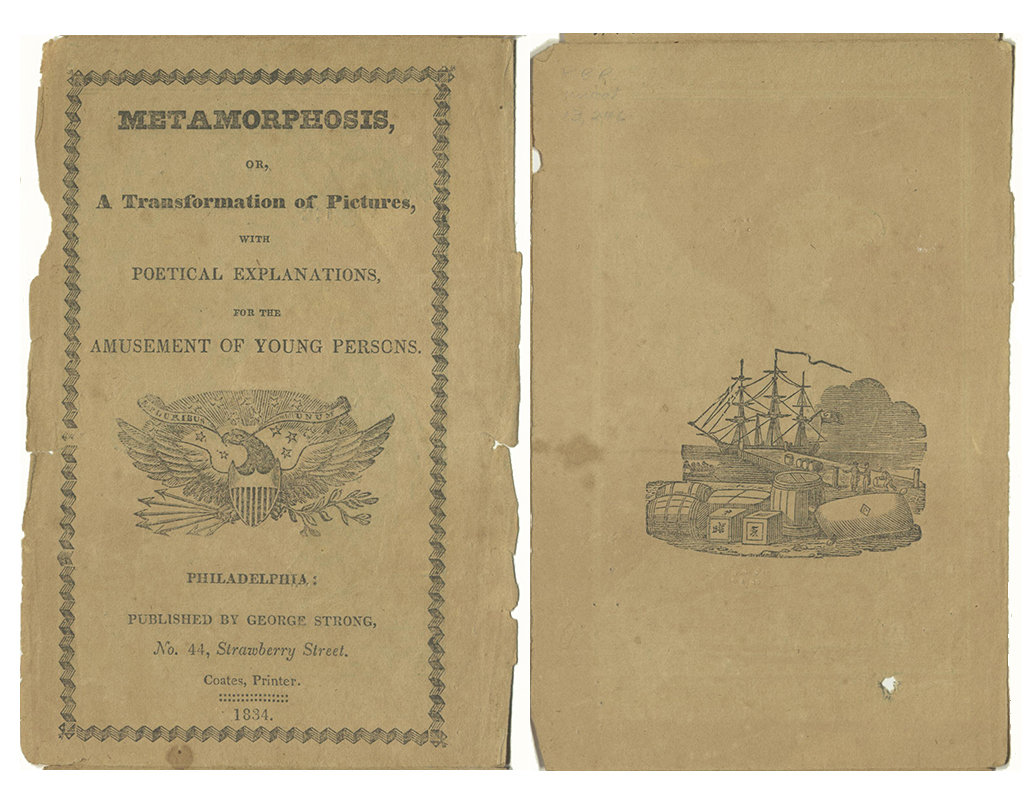

The book is based on an anonymous mid-17th-century British religious work, The Beginning, Progress, and End of Man. Near the end of the 18th century an altered and expanded set of verses, attributed to Benjamin Sands, began to be published in America in both English and German versions, with a hundred editions appearing in the following 75 years. Physically it is made up of a single sheet, printed on both sides, with a central four panel strip. Separate flaps above and below flank each of the panels; the entire object is then accordion folded to resemble a chapbook.

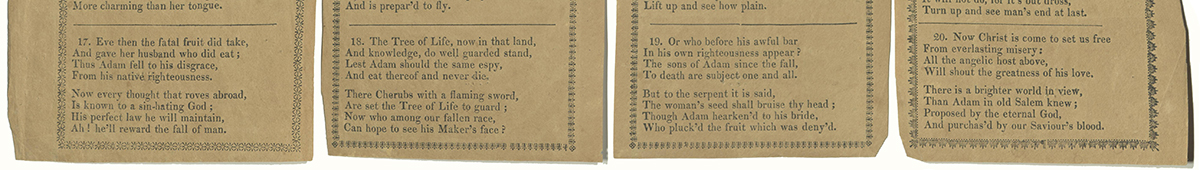

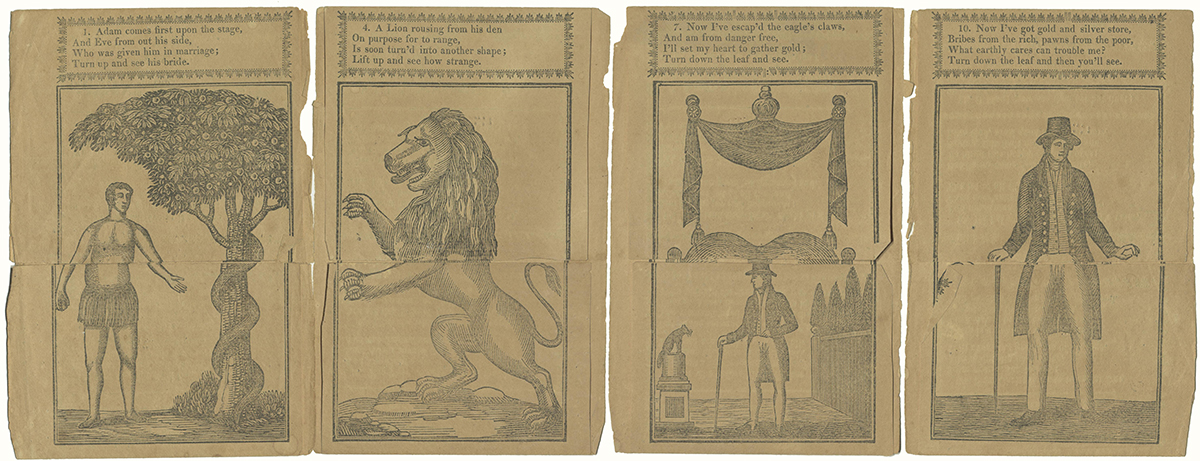

When the folded object is first opened out, four scenes are revealed, each with a verse that introduces the topic – and tells the reader what to do next. The first scene shows Adam and Verse 1:

Adam comes first upon the stage,

And Eve from out his side,

Who was given him in marriage;

Turn up and see his bride.

When you follow the instructions and turn up the top flap, both Eve and the serpent – tempting her – appear. The verse nearer the image is labeled “2” and it names Eve, comments on the transformation, and promises further entertainment:

When you follow the instructions and turn up the top flap, both Eve and the serpent – tempting her – appear. The verse nearer the image is labeled “2” and it names Eve, comments on the transformation, and promises further entertainment:

Here Eve in shape you may behold,

One body showeth two;

Once more do but the leaf downfold,

And it’s as strange to view.

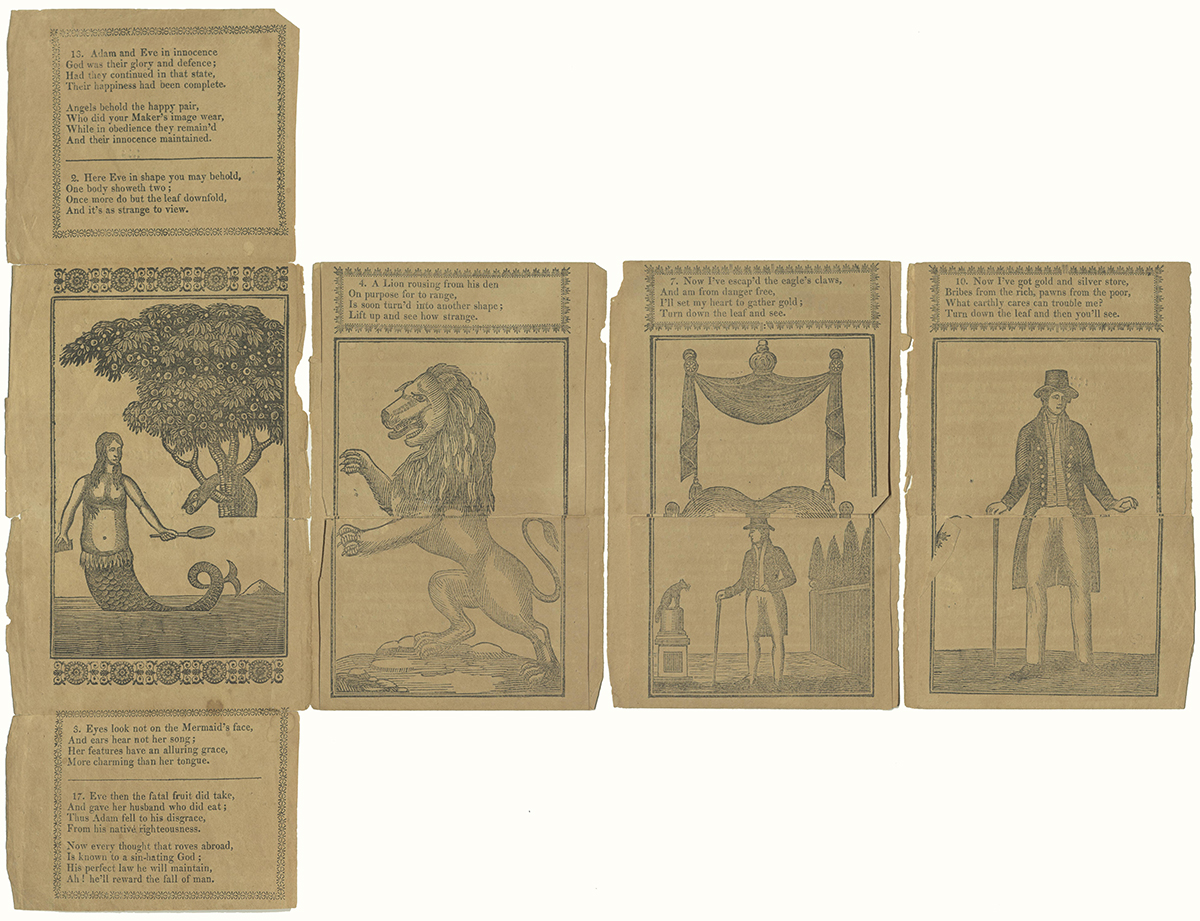

Eve turns into a mermaid, described by Verse 3:

Eve turns into a mermaid, described by Verse 3:

Eyes look not on the mermaid’s face,

And ears hear not her song:

Her features have an alluring grace,

More charming than her tongue.

We will come back to the additional verses, those printed further out the leaves.

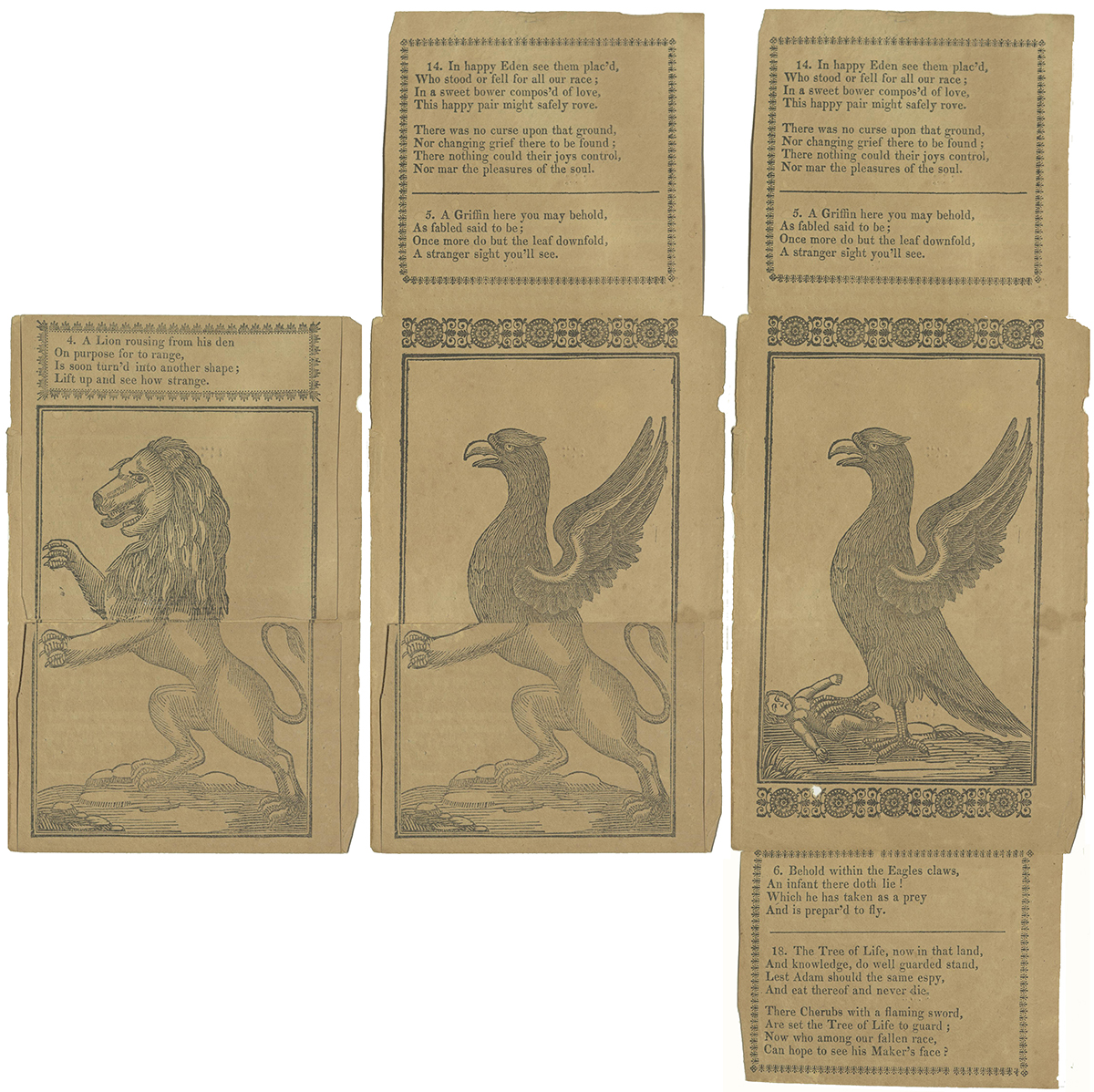

Each segment of the book is read and opened in this way. To make the transformations easier to see, the image above and the next two show the successive versions of the remaining panels. In panel 2, a lion turns into a griffin, which then becomes an eagle menacing an infant. Again the first and second verse tell the reader which flap to open next, and describe both the metamorphoses as “strange.”

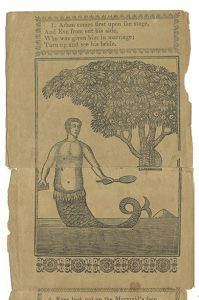

In the third panel, a young man is revealed as the victim of the eagle, happily saved. Turning the lower flap down first, according to the instructions reveals that he has unfortunately, grown up obsessed with accumulating wealth. Having become rich, he believes he is invincible:

A purse with gold and silver store

Has cur’d my heart, I’m sick no more;

And am from cares and dangers free;

What is there now can trouble me?

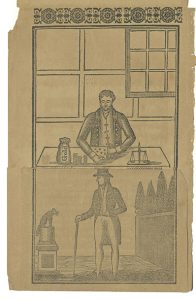

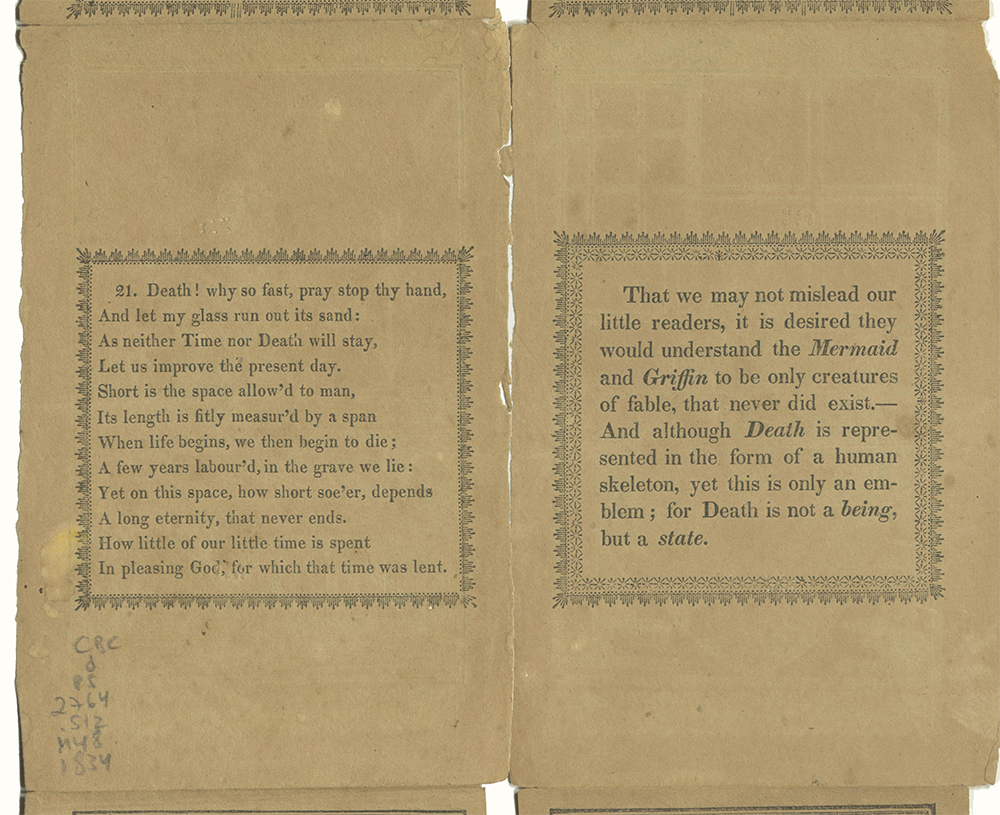

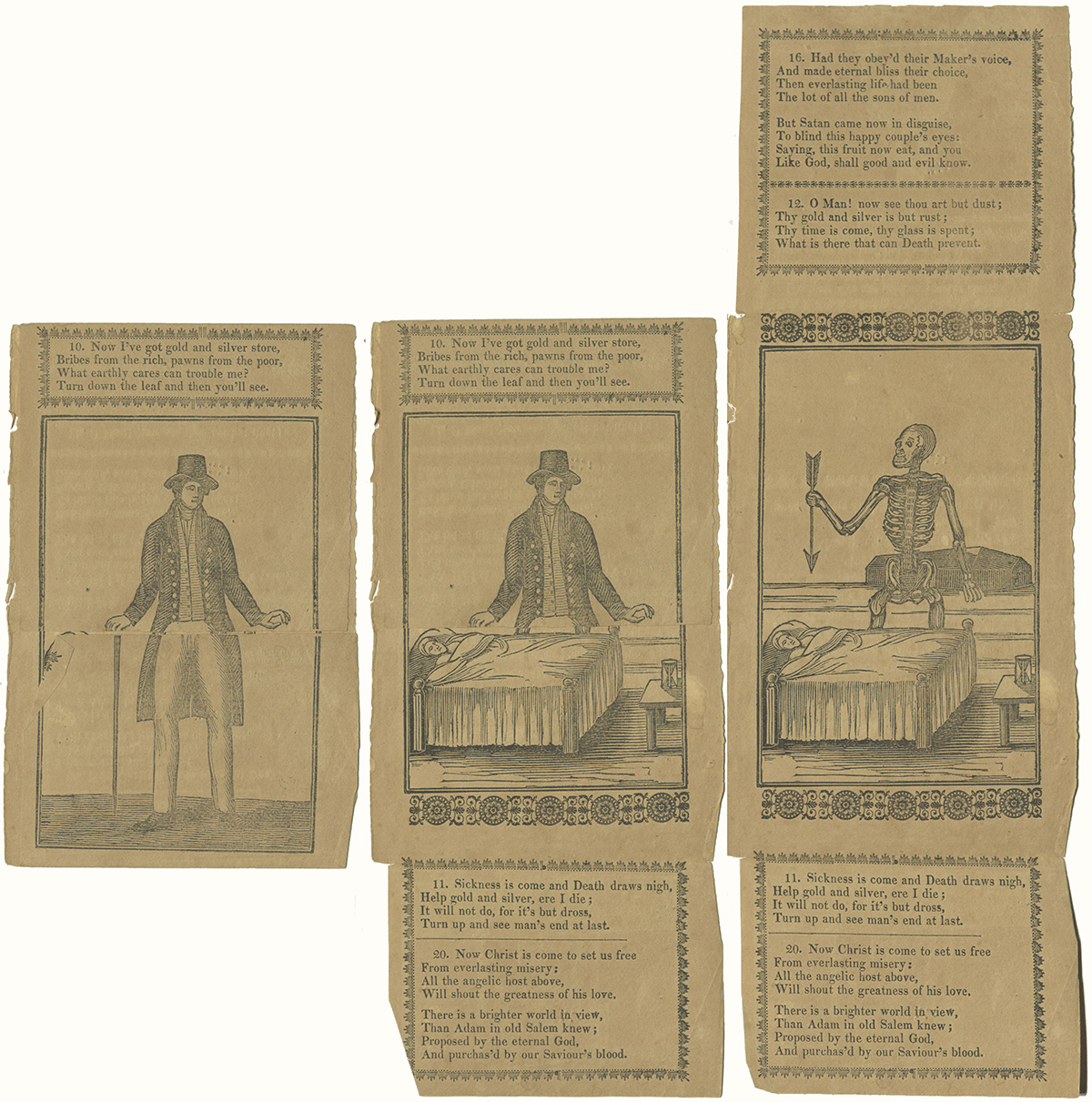

Cue the spooky music! His wealth is of no use to him when he becomes ill in the fourth panel and a familiar moral is presented:

O Man! Now see thou art but dust;

They gold and silver is but rust;

Thy time is come, thy glass is spent;

What is there that can Death prevent.

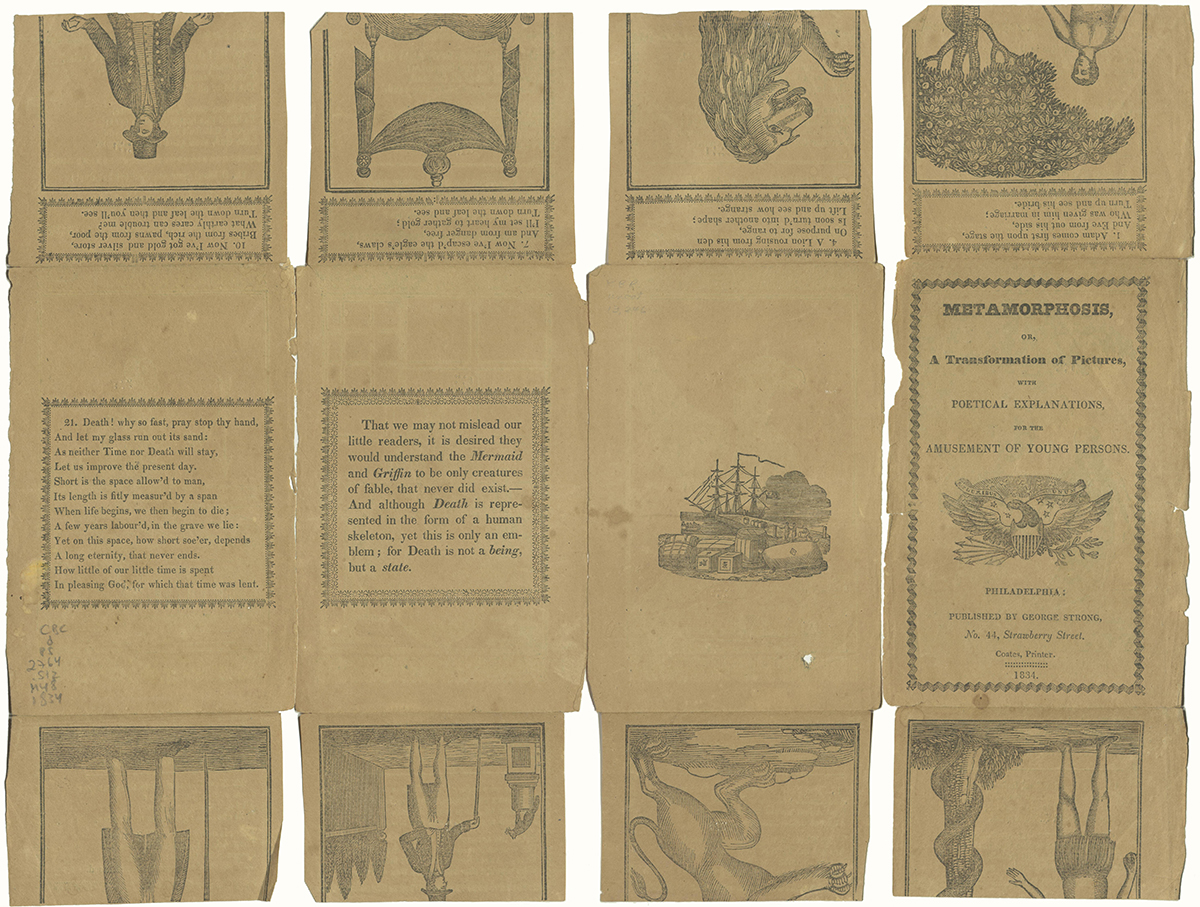

The story is finally revealed – or is it? When you have finished opening all the flaps you still have not engaged with the additional verses. And, of course the verse initiating the interaction with each panel is hidden on the back of the open flap, and the primary and intermediate images for each are no longer visible.

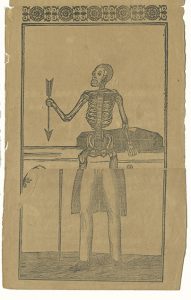

The supplementary verses continue commentary on the narrative. Jumping back up to the top left, the history of the Fall is rehearsed. Adam and Eve had everything they needed, but Satan convinced them to disobey God.In the verses revealed at the bottom, Eve takes the “fatal fruit” and carries Adam down with her to “disgrace.” Verses 18 and 19 mourn the separation of mankind from God, and Verse 20 proclaims salvation through Christ.

Closing the flaps and re-folding the sections lets the reader see the last verse, a meditation on the brevity of human life. On the final available panel the publisher added literal-minded remarks on imaginary animals and the the allegorical nature of the depiction of death, reflecting a tradition of iconoclastic Protestant religious thought strangely at odds with the densely emblematic book itself.

Closing the flaps and re-folding the sections lets the reader see the last verse, a meditation on the brevity of human life. On the final available panel the publisher added literal-minded remarks on imaginary animals and the the allegorical nature of the depiction of death, reflecting a tradition of iconoclastic Protestant religious thought strangely at odds with the densely emblematic book itself.

Of course, the original readers of the book also had the option of creating images against the intentions of the designers. They could turn Adam into a merman with the traditional symbols of vanity, the mirror and comb; make the miser count his money on his own head; or see Death strangely dressed in fashionable trousers, making new meanings – or perhaps new nonsense – from the sincere advice of the makers.

Another way to navigate the book is available in the digitization of our copy on the Internet archive at https://archive.org/details/metamorphosis-or-a-transformation-of-pictures-1834/

Sands, Benjamin. Metamorphosis : or, A Transformation of Pictures, with Poetical Explanations, for the Amusement of Young Persons. Philadelphia: G. Strong, 1834.

With the continuing closure of the Library, we are blogging regularly about books from the exhibition, The Girl’s Own Book. The exhibition’s run has been extended through the 2020-2021 academic year. Information about when it will open to visitors and related programming will be available when we are able to give it. Please follow us on Facebook or subscribe here for notices of new blog posts.

![Verse 13: Adam and Eve in innocence, God was their glory and defence : Had they continued in that state, Their happiness had been complete. Angels, behold the happy pair, Who did your Maker’s image wear, While in obedience they remain’d And their innocence maintained. Verse 14: In happy Eden see them plac’d, Who stood or fell for all our race; In a sweet bower, composed of love, This happy pair might safely rove. There was no curse upon that ground, Nor changing grief there to be found: There nothing could their joys controul [sic], Nor mar the pleasures of the soul. Verse 15: This land they freely might possess, And live in joy and happiness: Adam was lord of all the land, Made by the great all-forming hand. Eat, said the Lord, of all you see, Except one interdicted tree; And on this truth you may rely, You may not eat that lest you die. Verse 16 (not numbered): Had they obey’d their Maker’s voice, And made eternal bliss their choice, Then everlasting life had been The lot of all the sons of men. But Satan came now in disguise, To blind this happy couple’s eyes: Saying, this fruit now eat, and you Like God, shall good and evil know.](http://specialcollections.blogs.brynmawr.edu/files/2020/06/13through16.jpg)