One of the books Ellery Yale Wood collected was this glorious Three Bears, illustrated by Walter Crane in 1873. (Click on any image for a larger view.) It differs in a number of ways from the story of Goldilocks we all grew up with – and those differences are clues to the complex nineteenth-century history of this story.

One of the books Ellery Yale Wood collected was this glorious Three Bears, illustrated by Walter Crane in 1873. (Click on any image for a larger view.) It differs in a number of ways from the story of Goldilocks we all grew up with – and those differences are clues to the complex nineteenth-century history of this story.

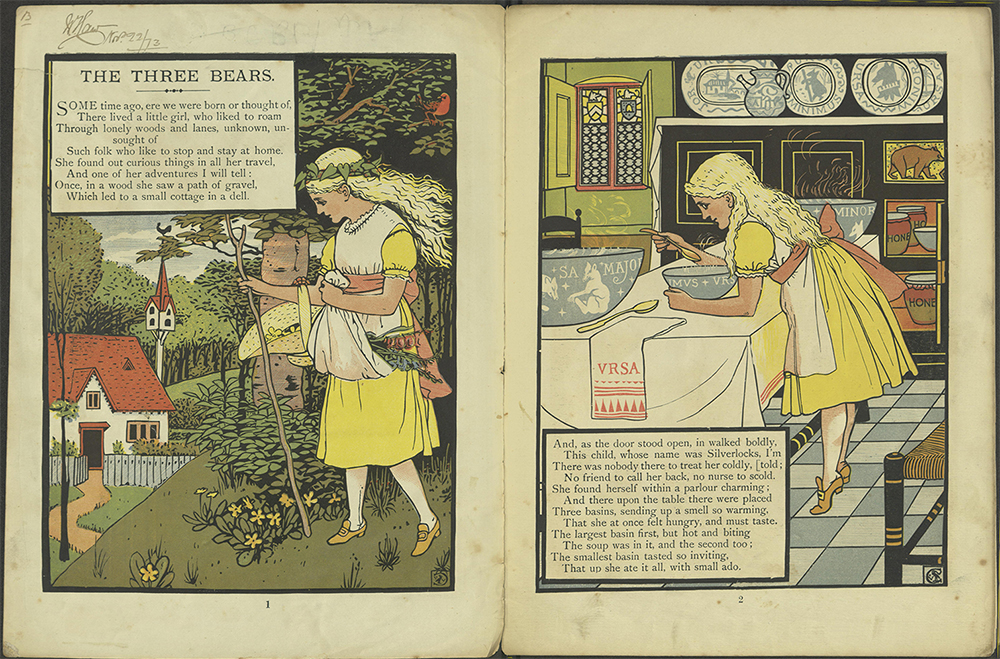

The images Crane begins with are exactly what we expect – but the poem contains a surprise: the little girl is called Silverlocks. In the first printed version of the story (which seems to be a folk tale that was not recorded until after it took a literary form), the intruder is not even a child. England’s Poet Laureate, Robert Southey, published “The Story of the Three Bears” in 1837. His intruder, who enters an unoccupied house, eats the occupants’ food, breaks their furniture, and tucks herself into their beds, is an “impudent, bad old Woman,” a vagrant who he says should be “taken up by the constable and sent to the House of Correction.”

The images Crane begins with are exactly what we expect – but the poem contains a surprise: the little girl is called Silverlocks. In the first printed version of the story (which seems to be a folk tale that was not recorded until after it took a literary form), the intruder is not even a child. England’s Poet Laureate, Robert Southey, published “The Story of the Three Bears” in 1837. His intruder, who enters an unoccupied house, eats the occupants’ food, breaks their furniture, and tucks herself into their beds, is an “impudent, bad old Woman,” a vagrant who he says should be “taken up by the constable and sent to the House of Correction.”

By the time Cundall’s Treasury of Pleasure Books for Young Children appeared thirteen years later, the child trespasser was firmly in place in popular culture. He says the story is better known with “Silver-Hair” and he substitutes her into Southey’s text. Thereafter a series of blonde girls, including Silver Locks, Golden-Hair, and eventually Goldilocks, imposed on the bears in an increasing number of illustrated books for children.

You probably remember that Goldilocks first tastes the porridge the bears have left on the table. She finds the first bowl too hot, the second bowl too cold, and the third bowl “just right.” Similarly the chairs are too wide, too narrow, and “just right,” and the beds too hard, too soft, and “just right.” This pattern is nearly universal in both modern and older tellings of the story. In fact, the expression “Goldilocks principle” has come to be used for situations where a point in the middle of a spectrum is most desirable. For example, astronomers have the earth orbiting the sun in a so-called “Goldilocks zone” – a distance from a star in which a planet’s temperature is neither too hot nor too cold for liquid water to exist.

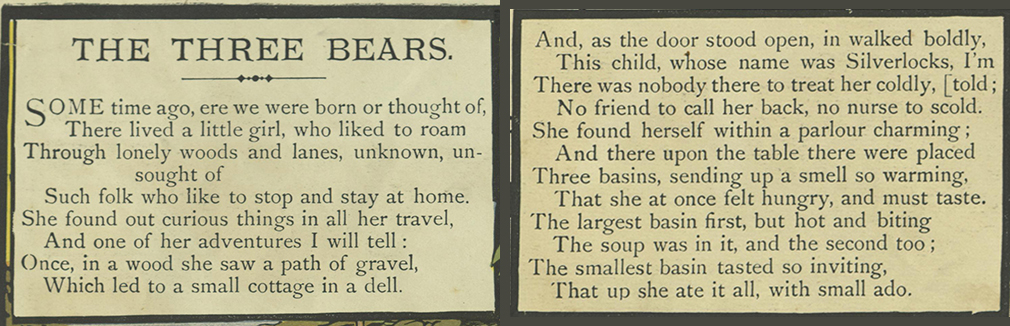

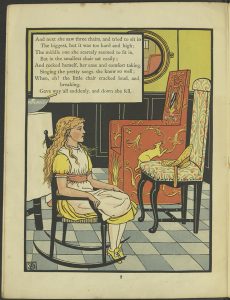

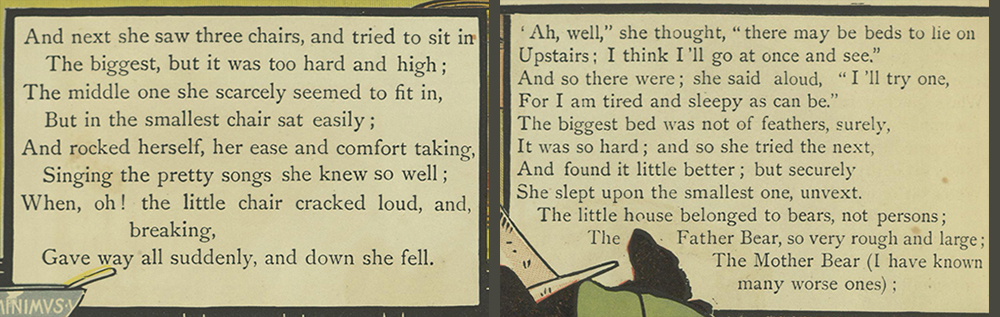

You probably remember that Goldilocks first tastes the porridge the bears have left on the table. She finds the first bowl too hot, the second bowl too cold, and the third bowl “just right.” Similarly the chairs are too wide, too narrow, and “just right,” and the beds too hard, too soft, and “just right.” This pattern is nearly universal in both modern and older tellings of the story. In fact, the expression “Goldilocks principle” has come to be used for situations where a point in the middle of a spectrum is most desirable. For example, astronomers have the earth orbiting the sun in a so-called “Goldilocks zone” – a distance from a star in which a planet’s temperature is neither too hot nor too cold for liquid water to exist. But Crane’s Silverlocks finds two of the soups “too hot and biting,” two of the chairs uncomfortable in ambiguously different but not necessarily opposite ways, and two of the beds too hard. The reason for this is unclear. It is true that the story has been put into verse (by an unknown poet), but other versions in verse preserve the “two extremes and a compromise” pattern.

But Crane’s Silverlocks finds two of the soups “too hot and biting,” two of the chairs uncomfortable in ambiguously different but not necessarily opposite ways, and two of the beds too hard. The reason for this is unclear. It is true that the story has been put into verse (by an unknown poet), but other versions in verse preserve the “two extremes and a compromise” pattern.

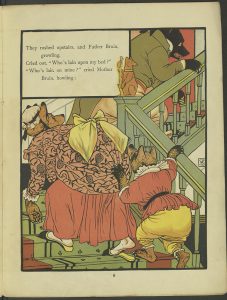

In this book it is only when the rightful inhabitants of the house return that we learn that they are “bears, not persons.” In most re-tellings, the story starts with the bears and there is no surprise.

In this book it is only when the rightful inhabitants of the house return that we learn that they are “bears, not persons.” In most re-tellings, the story starts with the bears and there is no surprise.

Of course Crane has been revealing this all along in his exuberant depiction of an Aesthetic Movement interior. The bears’ coat of arms in the stained glass window and painted chair, the decorated cabinet, the table linens, the labeled blue and white bowls, and the newel post sculpture that references the heraldic ragged staff and bear of the Earls of Warwick, all point to the owners’ nature.

Of course Crane has been revealing this all along in his exuberant depiction of an Aesthetic Movement interior. The bears’ coat of arms in the stained glass window and painted chair, the decorated cabinet, the table linens, the labeled blue and white bowls, and the newel post sculpture that references the heraldic ragged staff and bear of the Earls of Warwick, all point to the owners’ nature.

In another way, though, Crane is firmly in line with modern practice. Southey’s bears were a Great, Huge Bear; a Middle-sized Bear; and a Little, Small, Wee Bear and all of them were male. By the early 1850s they were often depicted as a large male, medium-sized female, and small cub, even when Southey’s text was used. By the 1860s they were Father, Mother, and Cub, as they are in Crane’s version.

In another way, though, Crane is firmly in line with modern practice. Southey’s bears were a Great, Huge Bear; a Middle-sized Bear; and a Little, Small, Wee Bear and all of them were male. By the early 1850s they were often depicted as a large male, medium-sized female, and small cub, even when Southey’s text was used. By the 1860s they were Father, Mother, and Cub, as they are in Crane’s version.

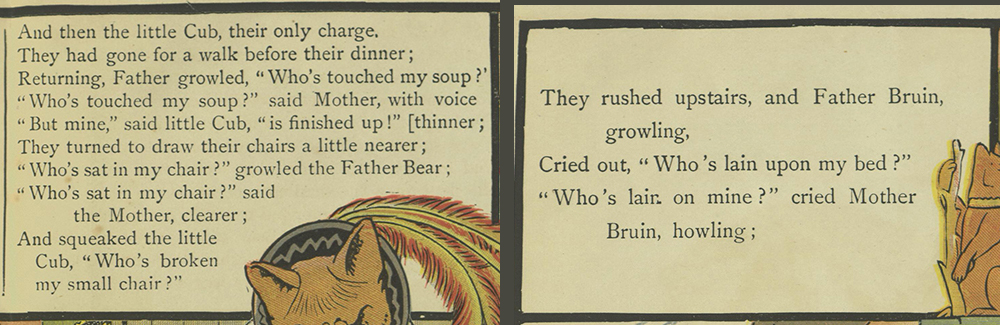

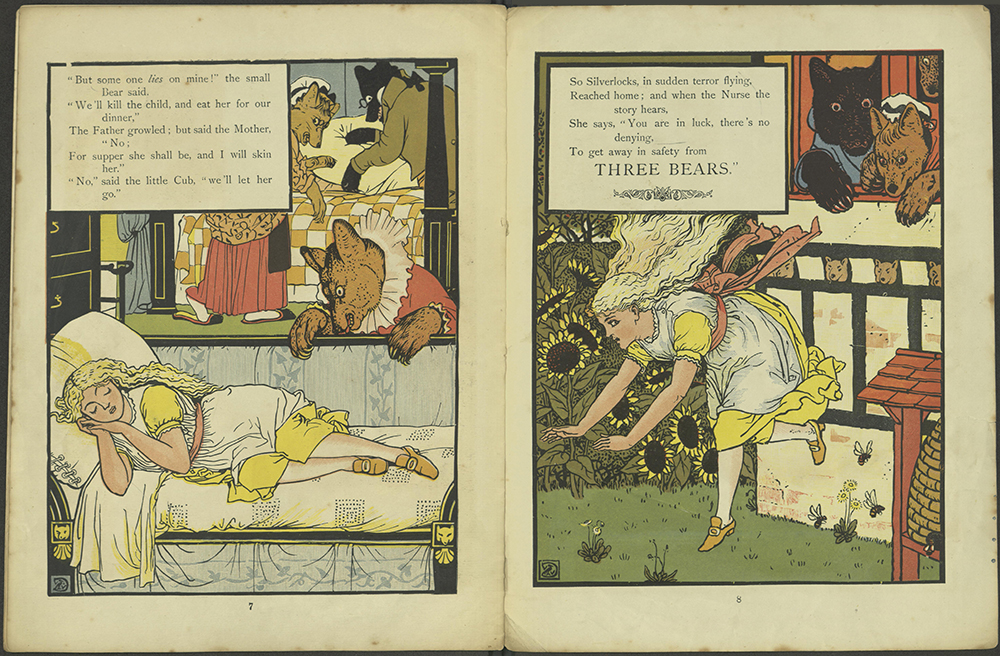

The frightening confrontation between the householders and the intruder was also in flux as the story settled into its modern form. Where Southey’s bears stand and watch the old woman jump out the window as soon as she wakens, for the next 60 or 70 years, the ursine responses are less certain.

The frightening confrontation between the householders and the intruder was also in flux as the story settled into its modern form. Where Southey’s bears stand and watch the old woman jump out the window as soon as she wakens, for the next 60 or 70 years, the ursine responses are less certain.

Crane’s Mother and Father Bear dispute whether to eat Silverlocks for dinner or supper, and they are not alone among their contemporaries. In the 1893 Rays of Sunshine, for example, the bears intend to eat the intruder until they see she is a child, and become ashamed of their bloodthirstiness. The general trend is away from violence, but it is not a straight path, and in this book, Silverlocks’ Nurse very reasonably tells her that she has had a lucky escape.

Crane’s Mother and Father Bear dispute whether to eat Silverlocks for dinner or supper, and they are not alone among their contemporaries. In the 1893 Rays of Sunshine, for example, the bears intend to eat the intruder until they see she is a child, and become ashamed of their bloodthirstiness. The general trend is away from violence, but it is not a straight path, and in this book, Silverlocks’ Nurse very reasonably tells her that she has had a lucky escape.

Crane, Walter, and Edmund Evans. The Three Bears. London: George Routledge & Sons, 1873.

Enjoy Crane’s Three Bears on the Internet Archive. The College’s copy of Southey’s work is not digitized, but you can read his original story there as well.

With the continuing closure of the Library, we are blogging regularly about books from the exhibition, The Girl’s Own Book. Please follow us on Facebook or subscribe here for notices of new blog posts.

Thank you, Walter Crane was married Mary Frances Andrews who was my Great Grandmother Alice Elizabeth Andrews Attwater’s sister. So I was delighted to see his art and read a older version of the story. I am a primary teacher and I would like to copy these pictures to share them with my students. I hope that is permissible. Judith Reavell

Hi, Judith Thanks for your note. Absolutely! You can also read the entire book, digitized, on the Internet Archive at https://archive.org/details/the-three-bears-walter-crane-1873. Enjoy!