This blog post was written by Hollister Pritchett, graduate student in archaeology at Bryn Mawr College. Holly was awarded an NEH Internship to work with select pieces of Greek pottery in the Bryn Mawr Art and Artifact Collections in the summer of 2011. One style of pottery that she is focusing on was produced in Ionia (also called East Greek), an area located in what is now present-day Turkey, while another style was produced in ancient Corinth, situated on the Greek mainland. Both styles of pottery were produced during the Greek Archaic period (ca. 800-480 BCE). Read on to learn more about her project:

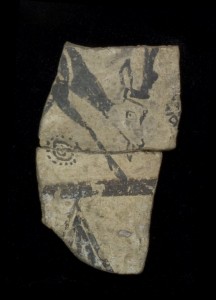

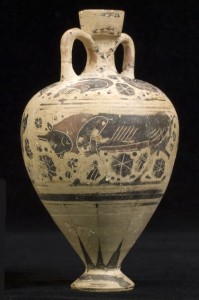

The East Greek Wild Goat Style, which flourished from approximately 680-570 BCE, originated mainly in the region of Miletus, an ancient Greek city located on the southern coast of modern Turkey. Generally the fired clay is light brown to reddish in color and the visible surface is covered in a cream slip. In decoration, the Wild Goat Style is an animal style with the fauna arranged in files around the vase. The animals that appear on the vases include spotted deer and hare, dogs, and geese. The species that is depicted most frequently, however, is the goat; the head bent to the ground to graze and its long horns curling back over the animal’s shoulder. The ornamentation used to fill the empty spaces is typically abstract forms, for example, triangles, hooked swastikas, and half-circles. The lowest portion of the vases is usually decorated with a chain of alternating lotus flower petals and buds, although on some vases the decoration is a chain of pointed rays instead.

The Wild Goat Style pottery was exported to other regions; excavations have turned up numerous examples from places that include cemeteries on the island of Rhodes, the ancient city of Tarsus in south-central Turkey, the Levant, and from Naukratis, an ancient Greek city situated at the Nile Delta in Egypt.

Similarly, Corinthian pottery, flourishing ca. 725-550 BCE, can also be decorated with files of animals. Animals that typically appear are lions (with their heads in profile) and panthers (always looking out at the viewer). Other species include geese and owls, mythological animals such as sphinxes and griffins, and unlike the Wild Goat Style, renditions of human figures. The fired clay ranges in color from light brown, to yellow, to yellowish-green, although it also can be pinkish, and the exterior slip is usually cream. Corinthian fine-ware pottery tends to be colorful with pale clay and black glaze enhanced by added red and white. The filling ornamentation, unlike the abstract forms of the Wild Goat Style, is floral, for instance, lotus palmettes, while rosettes with incised details are by far the most common. Often every available space on a vase can be filled with rosettes, crowding around the animals. The lower portion of many Corinthian wares is decorated with a chain of pointed rays, and combined with similar clay color and slip it can sometimes be difficult to discern whether a fragment is Corinthian or Wild Goat. Corinthian pottery was widely exported; vases have been discovered in excavations in all areas around the Aegean Sea.

The pottery in the Bryn Mawr Collections includes both complete vases as well as fragments. I study them thoroughly with respect to clay color, coarseness of the clay, paint, and decorations. My work includes creating complete entries in the Bryn Mawr data base EmbARK, inputting keywords, which will enable students and other users to access the records, as well as including descriptions and measurements. Both styles of pottery have their own specific repertoire of shapes and it is possible in many cases, after examination, to determine the type of vase from a fragment, for example, an oinochoe (a wine jug) or a kotyle (a cup). Additionally, by researching and examining the stylistic variations of the pottery’s phases, dates can also be assigned to each vase and fragment. I have also studied some of the various methods and techniques of ceramic analysis, with the intention of choosing select pieces to be sent to a lab in order to determine the location of manufacture, which in turn can aid in the study of pottery distribution, trade patterns, commerce, workshops, and emigration.