The story of Margery Meanwell, or Little Goody Two Shoes, is a Cinderella-type narrative that is driven by morality rather than fairy godmothers. First published in 1765, the story begins when Margery and Thomas Meanwell are orphaned. Thomas is sent off to sea; Margery goes to live in the home of friendly neighbors. There, she is given a pair of new shoes, and her excited exclamations over the fact leads to her name “Two Shoes.” Goody means “goodwife,” or as we might say, “missus,” and is a fondly joking name to call a little girl. The rest of the story is presented as a series of vignettes in which Margery overcomes adversity to become a teacher and a respected community member. Margery catches the eye of Sir Charles Jones, and they marry, making her Lady Jones. During the wedding her brother returns. The siblings live happily, made prosperous by their industry.

The popularity of Margery’s meritocratic story led to numerous editions and alternate versions of Little Goody Two Shoes. Within Bryn Mawr’s collections, we have condensed versions, versions in rhyme, story books where Margery makes cameo appearances, and several derivative works. Two such derivative works are The Renowned History of Primrose Prettyface and The Entertaining History of Little Goody Goosecap.

Both Primrose Prettyface and Goody Goosecap were issued by John Marshall, a British children’s book publisher who followed in the footsteps of John Newbery. Newbery had published Margery’s story initially, and Marshall capitalized on the trend. However, despite the similarities in themes and nicknames, there are significant differences among the three.

Primrose Prettyface also loses her parents at the beginning of her story. She meets Lady Worthy, who provides her with books that Primrose uses to teach other children. Primrose later takes a position as a maid for the family of Squire Homestead. After leaving Squire Homestead, Primrose finds her way back to Lady Worthy, working as a maid, then as a lady’s companion. Eventually, Lady Worthy’s son returns from university, and after he and Primrose form an attachment, they marry. There are two child-deaths in Primrose Prettyface that function as moral stories. First, one of Primrose’s students, a little boy, wanders off and drowns in a river. The other instance is a house fire in which the cruel son of Squire Homestead and a footman perish.

Goody Goosecap also recounts the story of an orphan, “Fanny Fairchild.” Her neglectful uncle spends her inheritance and sends Fanny to a charity school. She is later adopted by Mrs. Bountiful who takes her to London and introduces her to society. After they return to the country, Mrs. Bountiful’s son returns from the East Indies and is attracted to the 16-year-old Fanny. In an unexpected stroke of luck, Fanny’s estranged uncle dies, leaving her a fortune of 10,000 pounds. Mrs. Bountiful becomes very sick and expresses a dying wish to see Fanny marry her son. But she recovers, and Fanny establishes herself as a teacher before her marriage, instructing local children on how to be both good and wise. Finally, after much anticipation, Fanny and Mr. Bountiful marry. Goody Goosecap also includes a cautionary incident. As in Primrose Prettyface, a little girl wanders off, but in this story her punishment takes the form of violent kidnappers.

These two derivative works differ tonally and thematically from Goody Two Shoes with their inclusion of loving marriage as a reward for industry and goodness. In Margery’s story, marriage comes as an afterthought; we know little of the man she marries except that he is older than she. Margery’s happy ending instead revolves around the return of her brother. The sons of Mrs. Bountiful and Lady Worthy effectively displace Margery’s brother in the narrative. All three men spend a significant portion of the stories abroad and only return once the heroine has matured.

Replacing Tommy with a romantic figure simplifies the story. Unlike Goody Two Shoes, there are no longer two male companions competing for the heroine. It also transforms the stories of Primrose Prettyface and Goody Goosecap into more mature romances, as we see the growth of each relationship. Margery, in contrast, ends up exactly where she began at the end of her story, at her brother’s side. Despite being married to a gentleman, his character remains vague and the reader focuses more on the reunion of the siblings. The Little Goody Two Shoes narrative from the 1760s took on many different forms following its initial publication, and in Primrose Prettyface and Goody Goosecap, we see Margery’s story maintain its instructive status but also evolve as a romance.

Both derivative works are didactic; the boys who die and the girl who is kidnapped are not sympathetic characters, but rather rhetorical devices. The narrators urge us to scold the children for being naughty and disobedient. Whenever a child is harmed, the reader is meant to learn from their mistakes: do not disobey your parents or you might die a horrible death. By increasing the stakes in both stories, the authors privilege moralizing themes.

All three stories teach their readers to be industrious and obey, as well as read (and, presumably, buy) more books in order to move up in the world. Margery, Fanny, and Primrose are paragons of industry and obedience, and therefore are rewarded. Margery gains material wealth and reunites with her brother by the end of her story. She no longer has to sleep in a barn because her virtues and knowledge make her eligible for a successful marriage. Primrose and Fanny find similar material wealth, but also achieve loving marriages.

Reading all three of these stories back-to-back made their similarities clear, but I also noticed how Marshall’s books deviate from Goody Two Shoes. Margery’s story is very episodic and therefore the characters are less developed and the story does not flow. I personally found Primrose Prettyface and Goody Goosecap more enjoyable because of their recurring casts of characters. Primrose and Fanny are also allowed more growth in their stories, as they develop relationships. Margery’s closest relationship is with her brother, who is absent for the majority of the story. Each book was written with the intention of teaching simple lessons on learning and industry to young readers, but the stories of Primrose and Fanny stand out because of their attention to relationships and character growth.

Elinor Berger, BMC 2022

The Entertaining History of Little Goody Goosecap: Containing a Variety of Amusing and Instructive Adventures. London: Printed for John Harris, & Baldwin and Cradock, by S. and R. Bentley, 1828.

Goldsmith, Oliver and John Giles. The History of Goody Two Shoes. Embellished with Col’d. Engravings. London: Published by R. Miller; Old Fish Street, 1823-1830.

Marshall, John. The Renowned History of Primrose Prettyface. London: Printed in the year when all little boys and girls should be good, and sold by John Marshall and Co. No. 4, Aldermary Church Yard, Bow Lane, 1783.

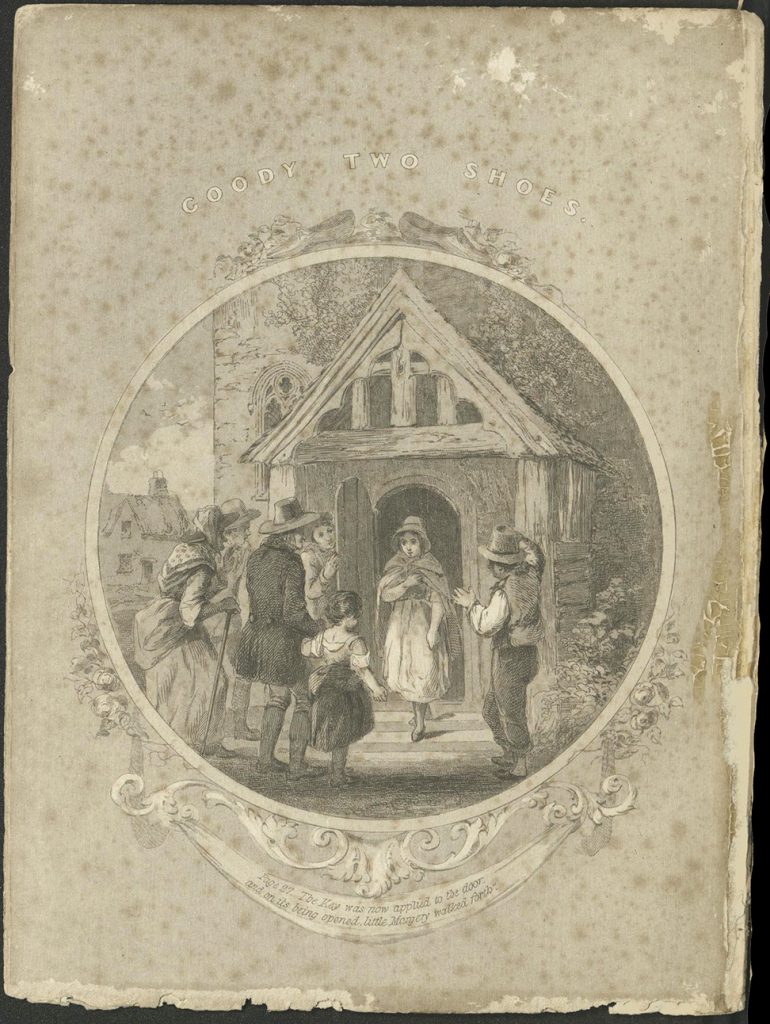

The Renowned History of Goody Two-Shoes, Otherwise Called Margery Meanwell: With Some Account of Her Brother Tommy. G. P. Nicholls, engraver, and Francis William Topham, illustrator. London: James Burns, 17 Portman Street, Portman Square, 1845.