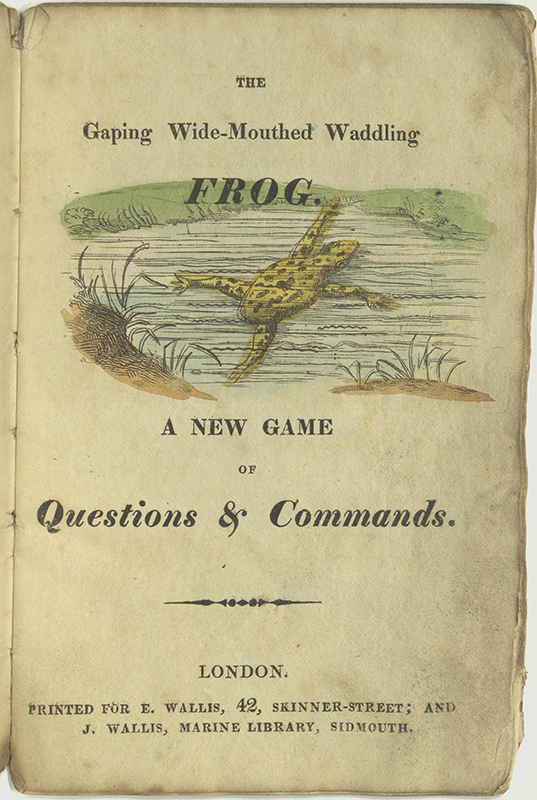

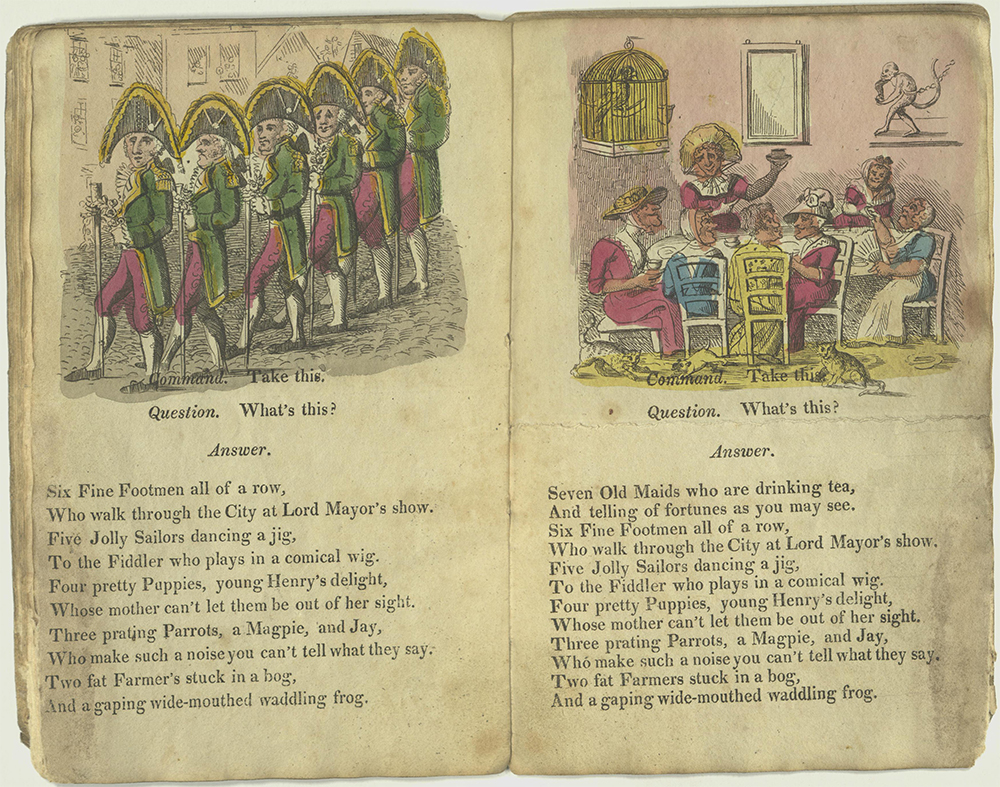

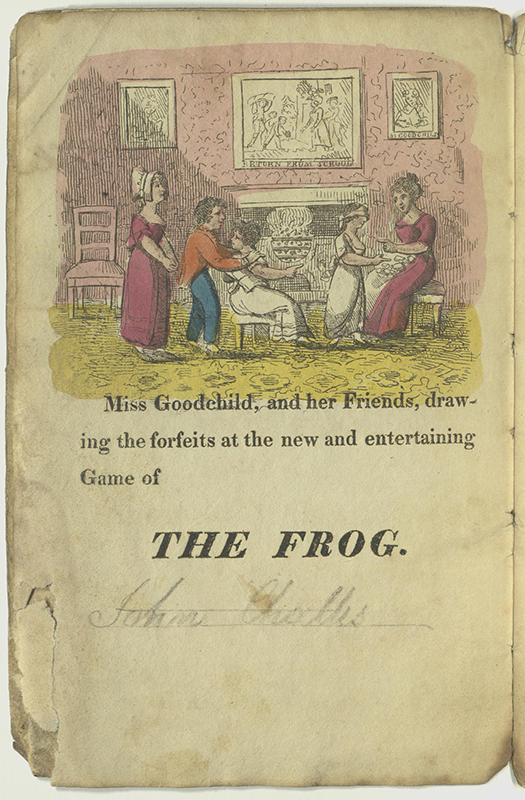

In April 1819, Mrs. Wake inscribed her gift to young John Challis – a copy of The Gaping Wide-Mouthed Waddling Frog: A New Game of Questions & Commands. John carefully wrote his name in pencil on the first illustrated page. These are facts. We have to imagine, though, what happened when John gathered friends and family to play the “new game.”

In April 1819, Mrs. Wake inscribed her gift to young John Challis – a copy of The Gaping Wide-Mouthed Waddling Frog: A New Game of Questions & Commands. John carefully wrote his name in pencil on the first illustrated page. These are facts. We have to imagine, though, what happened when John gathered friends and family to play the “new game.”

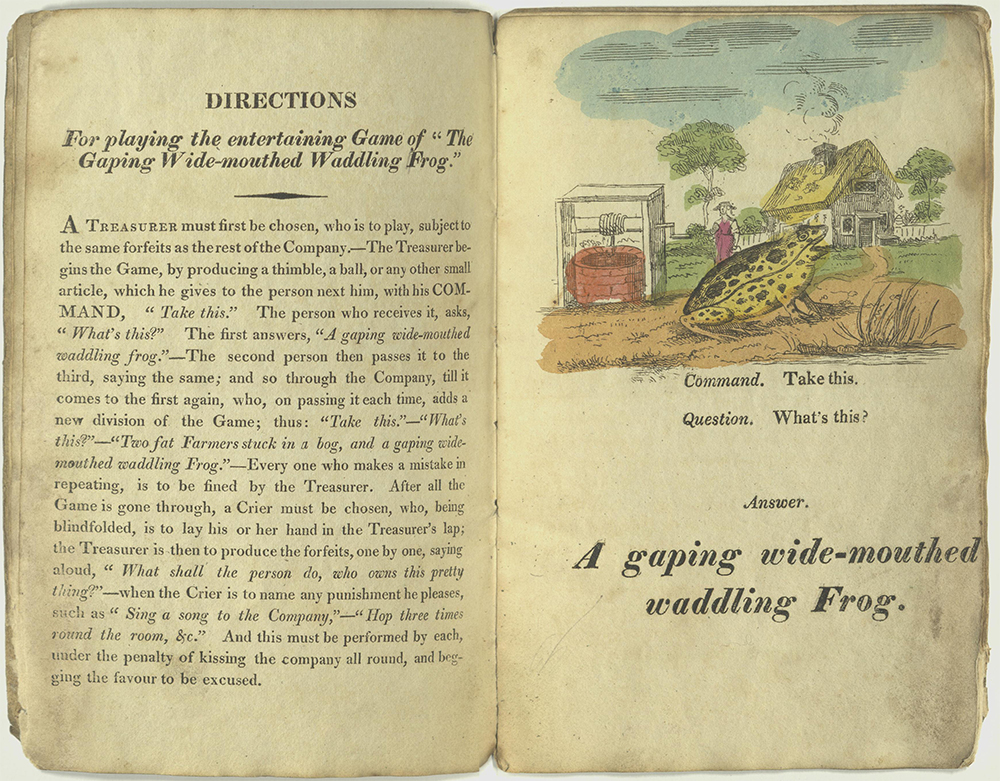

Following the instructions in the book, they chose a Treasurer, perhaps John’s sister Lettice (who wrote her own name in the book sometime later). She took a thimble from her reticule, handed it to the child to her right and said, “Take this.”

Following the instructions in the book, they chose a Treasurer, perhaps John’s sister Lettice (who wrote her own name in the book sometime later). She took a thimble from her reticule, handed it to the child to her right and said, “Take this.”

The little neighbor asked, “What’s this?”

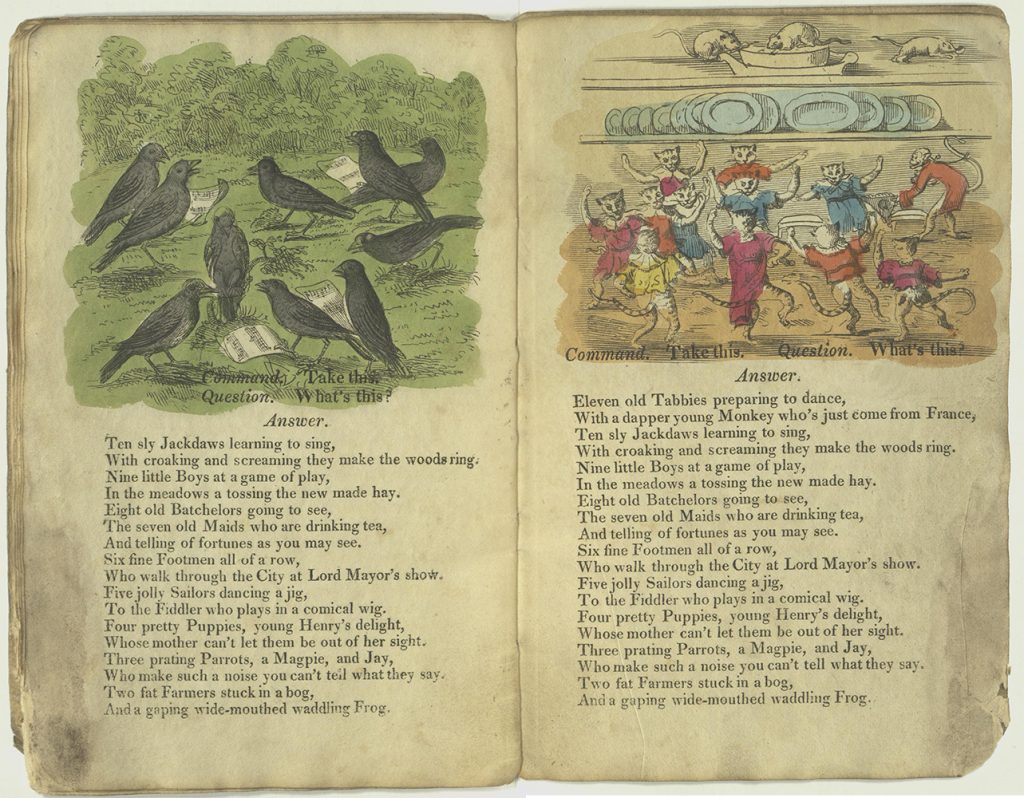

And Lettice replied, “A gaping wide-mouth, waddling Frog.” Each player, in turn, passed the thimble to their right, and the same dialog was exchanged between each pair.

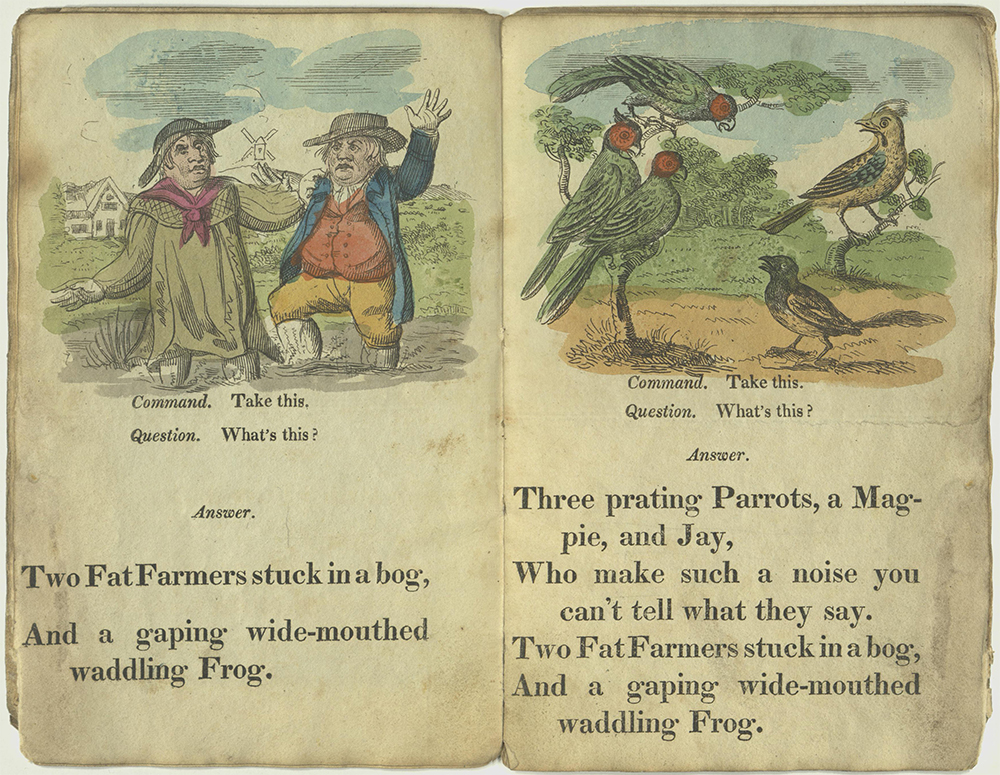

When the thimble got back to Lettice, she handed it to her neighbor again, but her response to “What’s this?” was now “Two fat farmers stuck in a bog, and a gaping wide-mouth, waddling Frog.” And the game proceeded round and round, adding a line or two with each repetition.

When the thimble got back to Lettice, she handed it to her neighbor again, but her response to “What’s this?” was now “Two fat farmers stuck in a bog, and a gaping wide-mouth, waddling Frog.” And the game proceeded round and round, adding a line or two with each repetition.

Every time a player made a mistake, they had to hand over some trifling item – a forfeit – to the Treasurer. When the memory part of the game finished, the forfeits began. A Crier was chosen, and blindfolded. Lettice picked one of the objects, a handkerchief or a ring perhaps, and asked the crier to name a punishment for the owner. The assigned tasks were supposed to provoke enjoyment for all; the person had to sing a song or hop around the room or recite a tongue twister in order to retrieve their possession.

Every time a player made a mistake, they had to hand over some trifling item – a forfeit – to the Treasurer. When the memory part of the game finished, the forfeits began. A Crier was chosen, and blindfolded. Lettice picked one of the objects, a handkerchief or a ring perhaps, and asked the crier to name a punishment for the owner. The assigned tasks were supposed to provoke enjoyment for all; the person had to sing a song or hop around the room or recite a tongue twister in order to retrieve their possession.

There was a fashion in the eighteen teens for children’s books presenting cumulative rhymes as competitive games. Edward Wallis offered not just The Frog but also The Pretty, Young, Playful, Innocent Lamb and The House that Jack Built between 1815 and 1818. At the same time, John Marshall supplied The Hopping, Prating, Chatt’ring Magpie; The Pretty, Playful, Tortoise-Shell Cat; The Frisking, Barking, Lady’s Lap-Dog; and The Noble, Prancing, Cantering Horse. All are subtitled A New Game of Questions and Commands.

There was a fashion in the eighteen teens for children’s books presenting cumulative rhymes as competitive games. Edward Wallis offered not just The Frog but also The Pretty, Young, Playful, Innocent Lamb and The House that Jack Built between 1815 and 1818. At the same time, John Marshall supplied The Hopping, Prating, Chatt’ring Magpie; The Pretty, Playful, Tortoise-Shell Cat; The Frisking, Barking, Lady’s Lap-Dog; and The Noble, Prancing, Cantering Horse. All are subtitled A New Game of Questions and Commands.

This raises two questions: where did these poems suddenly come from, and why are they called a new game of questions and commands?

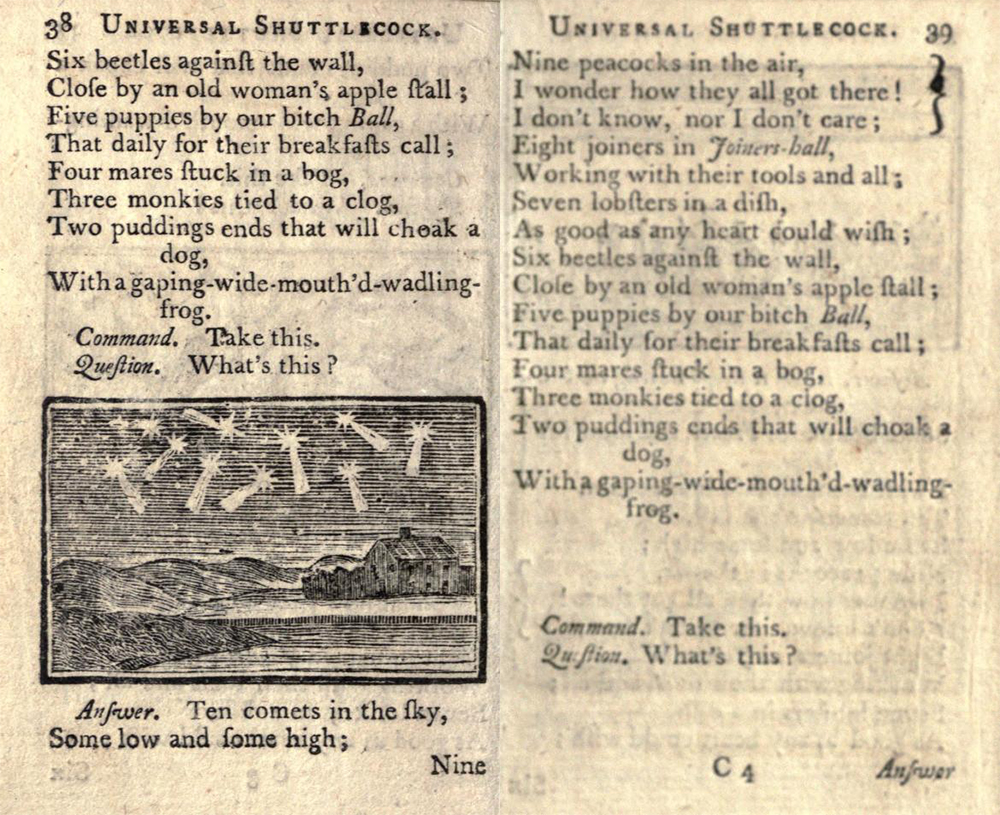

A poem called “The Gaping Wide-Mouthed Waddling Frog” first appeared in The Top Book of All, for Little Masters and Misses in 1760, then in 1790 in The Universal Shuttlecock, and around 1800 in Mirth Without Mischief. Surprisingly, the poem Wallis printed differs from the earlier texts. Both versions begin with the familiar frog, but then the texts diverge. Of course, Wallis (or whoever wrote the poem for him) knew the original verses, but chose not to use them. Likewise, all the other poems were original works created by Wallis or Marshall to offer variety for the market they had created. Only “The House that Jack Built” (first printed in 1755 as a poem, although not a game) contains a traditional text.

That leaves the issue of “Questions and Commands.” In 1711, in an issue of The Spectator, Joseph Addison included the game among a list of innocent amusements for a winter night. And in The Vicar of Wakefield (1766), the family plays blind man’s buff, hot cockles, hunt the slipper, and questions and commands at a Michaelmas Eve party. It turns out to be an 18th-century parlor game, played by adults as well as youngsters: A “commander” asks each player a question. If they refuse to respond, or if the answer does not satisfy the other players, the commander names a punishment. It is easy to see how, like the redemption of forfeits in our book, this game could lead to hilarity, but also to humiliation and ill will. A cartoon by James Gillray, from 1788, depicts a range of responses to a saucy forfeit requiring a gentleman to stick his head under a lady’s dress, perhaps to kiss her foot.

The forfeits are the essential feature, then, on which the subtitle New Game of Questions and Commands is based. We cannot tell if it was Wallis or Marshall who thought of linking back to an old-fashioned game that was not really very appropriate for their young customers, but it must have been a successful branding decision, since they both retained it in repeated printings of their books.

The forfeits are the essential feature, then, on which the subtitle New Game of Questions and Commands is based. We cannot tell if it was Wallis or Marshall who thought of linking back to an old-fashioned game that was not really very appropriate for their young customers, but it must have been a successful branding decision, since they both retained it in repeated printings of their books.

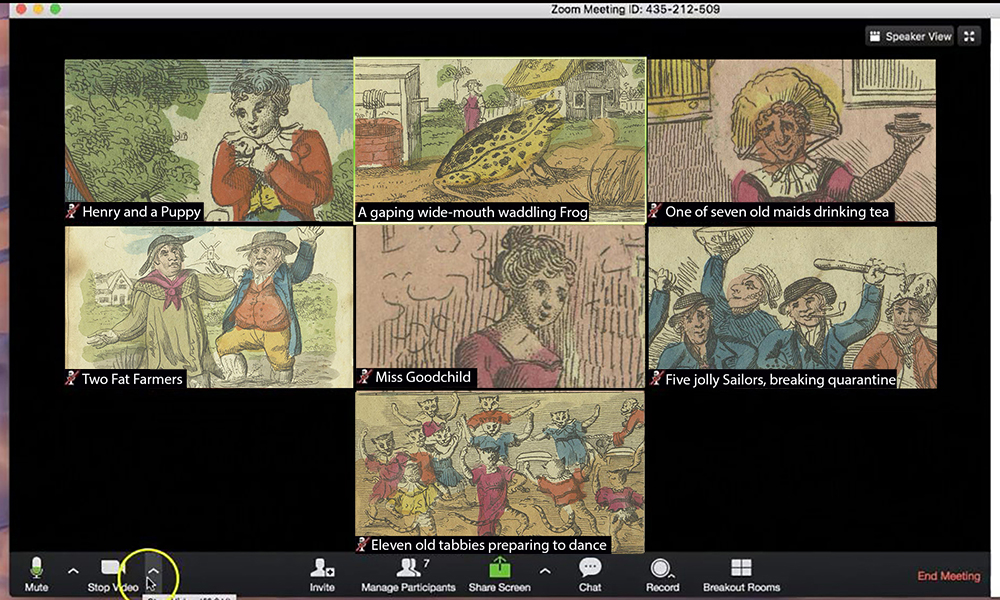

What about an even newer game of questions and commands? In this time of making one’s own fun and remote socializing, I’ve been considering playing The Frog on Zoom. Can modern players learn the poem by hearing it repeated? Do I have to be able to recite it perfectly to lead the game? How many of my friends would google the poem, find our scanned book on the Internet Archive, and cheat? What are the forfeits like in a digital age – do you still command someone to sing, or should they cue up a karaoke video? (The host of a Zoom meeting can mute an attendee, so it couldn’t be too bad.) Do they have to share the eighth picture from their camera roll or pictures folder? Must they say three times a tongue twister the host sends them by chat?

What about an even newer game of questions and commands? In this time of making one’s own fun and remote socializing, I’ve been considering playing The Frog on Zoom. Can modern players learn the poem by hearing it repeated? Do I have to be able to recite it perfectly to lead the game? How many of my friends would google the poem, find our scanned book on the Internet Archive, and cheat? What are the forfeits like in a digital age – do you still command someone to sing, or should they cue up a karaoke video? (The host of a Zoom meeting can mute an attendee, so it couldn’t be too bad.) Do they have to share the eighth picture from their camera roll or pictures folder? Must they say three times a tongue twister the host sends them by chat?

If you play the game, please report back!

Marianne Hansen, Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts

The Gaping Wide-Mouthed Waddling Frog. A New Game of Questions & Commands. London: Printed for E. Wallis, and J. Wallis, 1817.

Read our copy on the Internet Archive.

With the continuing closure of the Library, we are blogging regularly about books from the exhibition, The Girl’s Own Book. Please follow us on Facebook or subscribe here for notices of new blog posts.